Oluwatobiloba Ajayi, 24 October 2025

Oluwatobiloba Ajayi was commissioned as a writer-in-residence at Aspex Portsmouth to develop a text in response to Traces of the Non-Existent, the Spring 2025 exhibition at Aspex Portsmouth by multidisciplinary artist Ebun Sodipo. This residency and its outcome are presented as part of the Photoworks Photography Champions programme, and published in collaboration with Photography+

There is a deep, immeasurable blue that fills the room.

It is the blue of distance and of infinity, of the Iberian Peninsula, the bottom of the ocean, the Black Atlantic, the unknown, and of absence. This blue fills in spaces where nothing is held, as water fills in gaps, always in a rush to bathe a void. Histories, too, hold this same sense of urgency: a readiness to make whole from a sparsity of matter, an eagerness to kiss the shore and feel the truth of land.

But there are histories to which no one pays attention. Histories that echo in empty rooms, bursting at the seams when the door opens and air is let out, temporarily disbound as its partial vacuum is flooded in by attempts at the truth, waters that insist on occupying vacant space. We must tune ourselves to the frequency of these histories, dare to learn from, or dream of, stories in existence that are yet to be told. This is one such story:

On Vitória

You might find her in the orange grove, but then again, you might not. She is always careful to go when no ship is on-approach, dodging the watchmen lurking in their towers in citrus season: November to May. She moves silkily in her wrap skirt, turban, and vest, frolicking around the trees and picking the oranges just as they turn from green to a yellow suggestive of ripeness. If she’s not in the grove, she is moving through the streets, or at King’s Fountain with the other women gathering water. She tends to do as the women do. Yet Vitória did not arrive in Azores, an archipelago in the mid-Atlantic, as Vitória. On arrival, she was made Antônio. It can’t be said whether she was who she would become before she came. We are writing at the limits of the unknown, to borrow from Saidiya Hartman.

She came from Benin, and she immediately shed the clothes given to her by her master. Not to fully embrace what was traditionally worn by women, but to linger at the frayed edges of these gendered gestures. From Azores she would go to Lisbon, where she came to frequent the waterfront, running her business out of a house near the docks. From this house, outside of which there was often a queue of men, you could hear the water slapping against the dock pilings and smell the salt of the Atlantic Ocean. This was a welcome reprieve, an interruption to the rotten smells of the fishmonger, the putrid stench of the local merchants and butchers, and the tragic reek of Empire, which coalesced en masse on this particular Portuguese waterfront.

To return to the life of Vitória is to embrace a total aporia. We know of her from her criminal persecution and the ways she was described then: her actions vilified, justified, or leered upon in pure, violent curiosity. Still, the documented fact of her inquisition is held by other, unrecorded, truths. Everything we know is defined by what we can’t know.

Here, again, we must learn from the infinite lessons of water: its attunement to absence, its empathetic insistence on occupying dearths, and running to meet the cavity where it resides. Ebun Sodipo’s exhibition and imagined museum, Traces of the Non-Existent follows the waters’ path, bending the ear to listen to lives at risk of being lost. The artist recovers jewels, coins, pendants, and spoons that might have been used by Vitória, but also other trans women (as we might name them now) across history, in Azores, North and South Africa, and in Mesopotamia. These chimeric artefacts help us understand how she lived her life, what rituals she returned to and found reverie in, and how she loved herself.

Present throughout the exhibition is a ‘mid-Atlantic island,’ presumably a nod to Azores, where Vitória first arrived from Benin. To speak of a mid-Atlantic island is to acknowledge an unknown within the unknown. It is to cite location on the genesis of Blackness: the middle of the Atlantic when its shape started to catch, in the hold. It is a point of transformation, when one thing becomes another, or an other. On this pivot, too, might transness sit and waver? In what spaces does transness earn its name? For how did Vitória, and those Africans like her, shift from spiritually penetrable figures, understood as closer to the gods, at home, to politically contested bodies, stripped of any fullness, on arrival? We can only attempt to recollect these fragments.

Archaeology is about memory. Our gathering of the material remnants of the past tells of what we think is worth remembering, and what we choose to risk to the whims of forgetting. Put another way, the practice of remembering is a selective one. Archaeology, which traditional museology depends on, can also function to legitimise the violence of the gender binary. Excavations might lead to a body biologically read as male and the objects in its proximity, socially, as female. Then the job of the archaeologist is to spin a tale to fill in that perceived discrepancy. Sodipo instead attends to what falls through these cracks. A single question echoes through the room:

“How do we commemorate histories with limited material remnants, trapped in the violence and silencing of their time?”

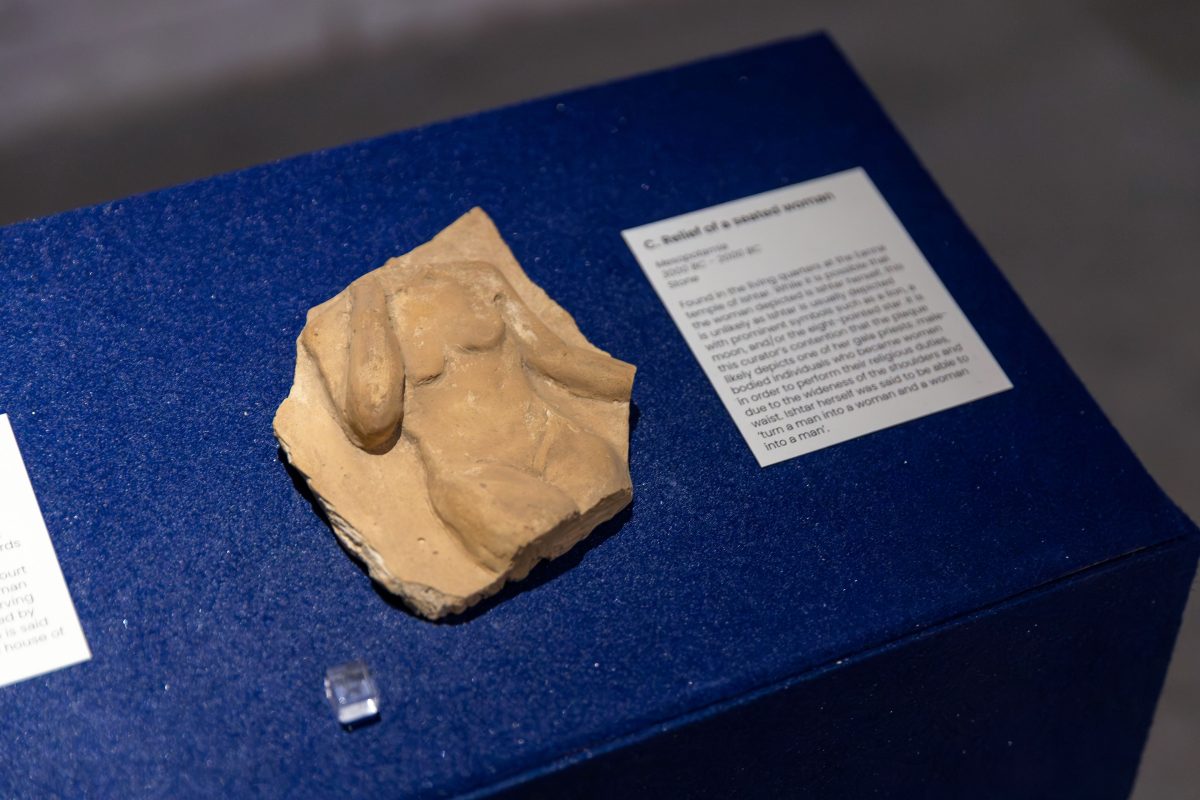

The artist reconstitutes a timeline that is as deep as her geographies are wide, pulling from the traces of the archive and acknowledging its inability to know fully. She creates 17th century brass plaques and amulets of precious metals depicting men with vulvas, and women with penises, and resurrects stone reliefs from 2000 BC, evoking the practices of male-bodied people who became women to perform religious rituals. Sodipo constructs a history, not from scratch, but from the traces of what we presume we know. These are suggestions of history, more capacious than rigid binaries account for. Moving as an archaeologist does, Sodipo builds lives through acts of faith.

In Sodipo’s fabulated museum, as in our traditional museums, there are absences where objects should be: labels of “Objects removed for study” sit in place of narrative. In Traces of the Non-Existent these gaps tell a different story. “Objects removed for study” repeats as a continued affirmation: trans histories, imagined and real, are worth studying, holding on to, and teaching again and again.

Even so, it is impossible to recover these unremembered Black trans histories without speaking to the present, to “the incomplete project of freedom,” as Hartman writes and knows too well. In line with her foremothers, Sodipo forces a collision between an imagined past and a documented present through her moving image work So, what brings you here? (2025). The found footage film is visible only through a Butchers curtain, dotted with images of overlapping hands reaching out in gestures of caress. It is as if those hands are guiding you to reckoning, as if those hands could buoy us all the way to the future.

These “image poems,” as the artist calls them, cut, layer, and collide fragments found across the internet. The artist collages memes, stock footage of marine animals, Nollywood movies, music videos, Ballroom clips, and films, “seizing these pieces of material by their throats, so they may tell different stories,” as she describes. Clips sizzle in corners and then disappear completely. Others insist on their dominance despite peripheral buried images and their discordant audios. Maya Angelou speaks of those “afraid to be pried loose from their ignorance,” and Sister Souljah belts “if my survival means your total destruction then so be it.” The references are many and constant, and it seems the only way to get a handle on things is to accept the fact that you can’t in full. The penultimate clip of Tokyo Toni, Blac Chyna’s mother sitting at the back of a car, hair flowing in the wind as she adjusts her wig, cuts a fitting image of Sodipo’s own nonchalance in the presentation of the film. It is the conviction of knowing the work continues in the compositional operations and cultural literacy of the audience’s mind.

As found footage is burned and ripped from its original context, a second question succeeds the first:

“What are our responsibilities to our sources?”

If our dealings with history have failed to hold the abundance of transness, then the veracity of sources becomes obsolete. Traces of the Non-Existent tackles this crisis of truth. Its artefacts are invented yet cited and presented as fact, and its “real” content is found on social media. Citational hierarchies collapse. Sodipo refuses responsibility to preordained truths, as poets do the fixed meanings of words. Her image poems usher her chosen materials into new forms, in the knowledge that stories exist whether or not they retain a trace, and the telling of them is no less valuable than that of others. Where the film meets the museum, we are doubly aware of the histories that had to have happened for those contemporary moments to exist. History explodes to become whole again.

To hold on to history is to hold too its slipperiness, its propensity to ooze through the gaps between fingers. Vitória’s is only one tale and we must look for others. We must listen attentively to the calls from spectres of the past, or longings of the present. When antagonised, Vitória would throw stones at her adversaries and bare her breasts. So too we must launch our munitions in defence of the unseen.

Taking in her reflection in the ocean, Vitória holds a pair of gold earrings against her lobes. Dissatisfied, she swaps them for another pair, these ones specifically made for her and bearing a motif from the artisans of home. Every now and then her face crumples in the water’s rippled surface, but she knows it is still there. Vitória thinks of where these earrings will go when she is no longer here, aware of the inevitability of her departure. She hopes, tirelessly, they might one day fall into the hands of a woman like her.

Oluwatobiloba Ajayi is a London-based artist and writer. Informed by anti-, post-, and decolonial theory and Black radical thought, her work centres on the importance of space within Black feminist epistemologies. She holds a BA in Architecture from Princeton University and an MA from the Courtauld Institute of Art, where she specialised in post-war Black British Art, and her writing has appeared in The Architectural Review, Elephant, Worms, and Frieze, among others.