In this interview from 2007, Photoworks Editor Gordon MacDonald talks to Billingham about his early career and his moves back to the snapshot aesthetic of his first, and most successful project, Ray’s a Laugh.

Richard Billingham’s story is an oddity in the history of British art. Having been ‘discovered’ as a painting student at Sunderland University, he rapidly went on to become one of the only household names in British photography and to become recognized, nationally and internationally, as an important artist. In 1997 he won the Citibank prize and in 2001 he was shortlisted for the Turner prize.

GM. Gordon MacDonald

RB. Richard Billingham

GM I wonder what first drew you towards art?

RB I learned to read quite late, maybe 7 or 8 years old. Not because I was thick but because my parents didn’t bother pushing me. When I did learn I wanted to read everything and a big world opened up to me. I would read art books in the local library. I probably read most of them – there weren’t many there but I got to know who Picasso was. Constable was the artist who influenced me the most. He was a naturalist and his empirical approach to landscape painting has interested me all this time. Since I was 11 I have been interested in nature. I lived in a tower block and nature, to me, was escapism. I wanted to paint landscapes but it was, like, impossible at the time.

GM How did your parents feel about you taking up art?

RB They were indifferent to it. They probably liked it because, if I was drawing, I was occupied and didn’t need looking after.

GM How did the photographs start?

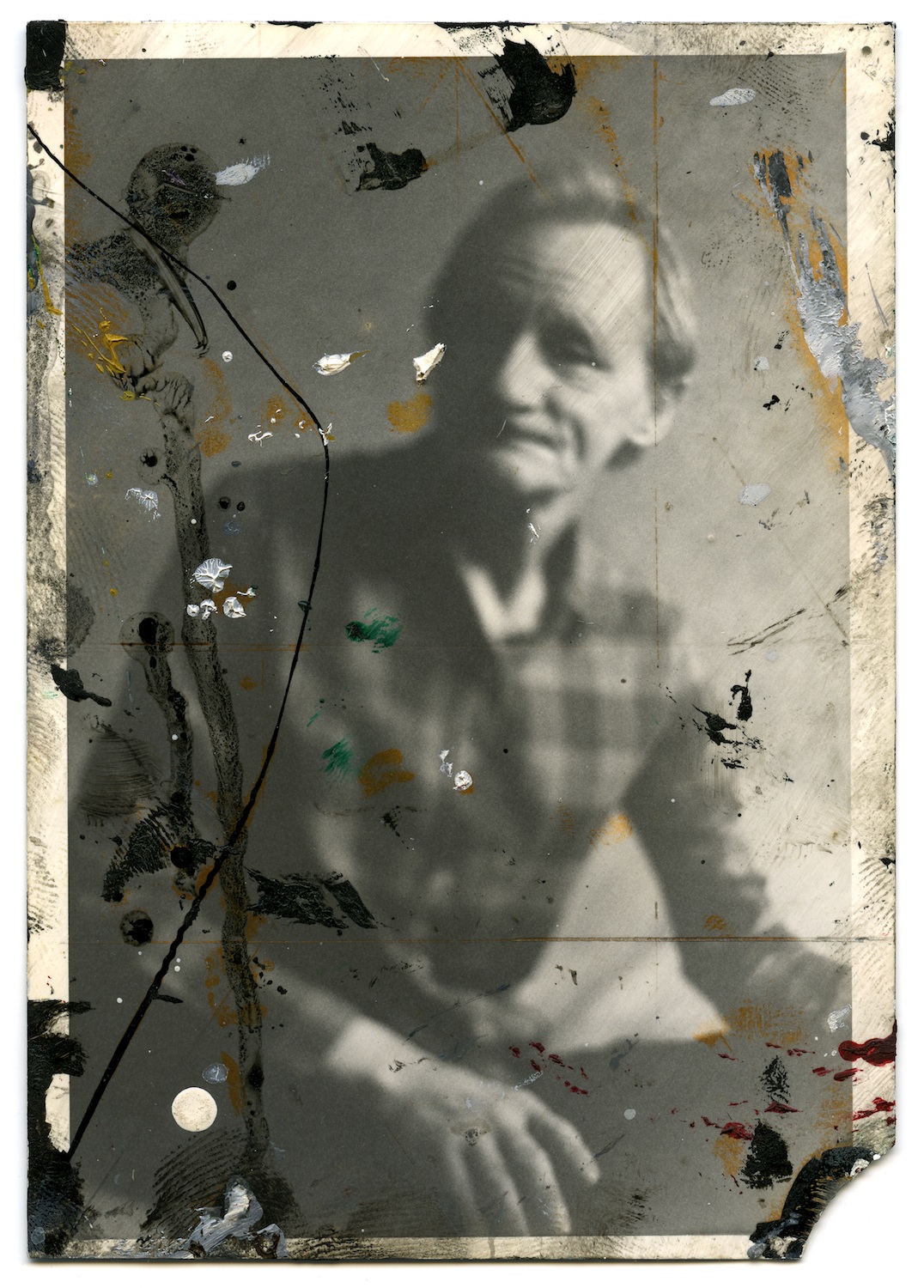

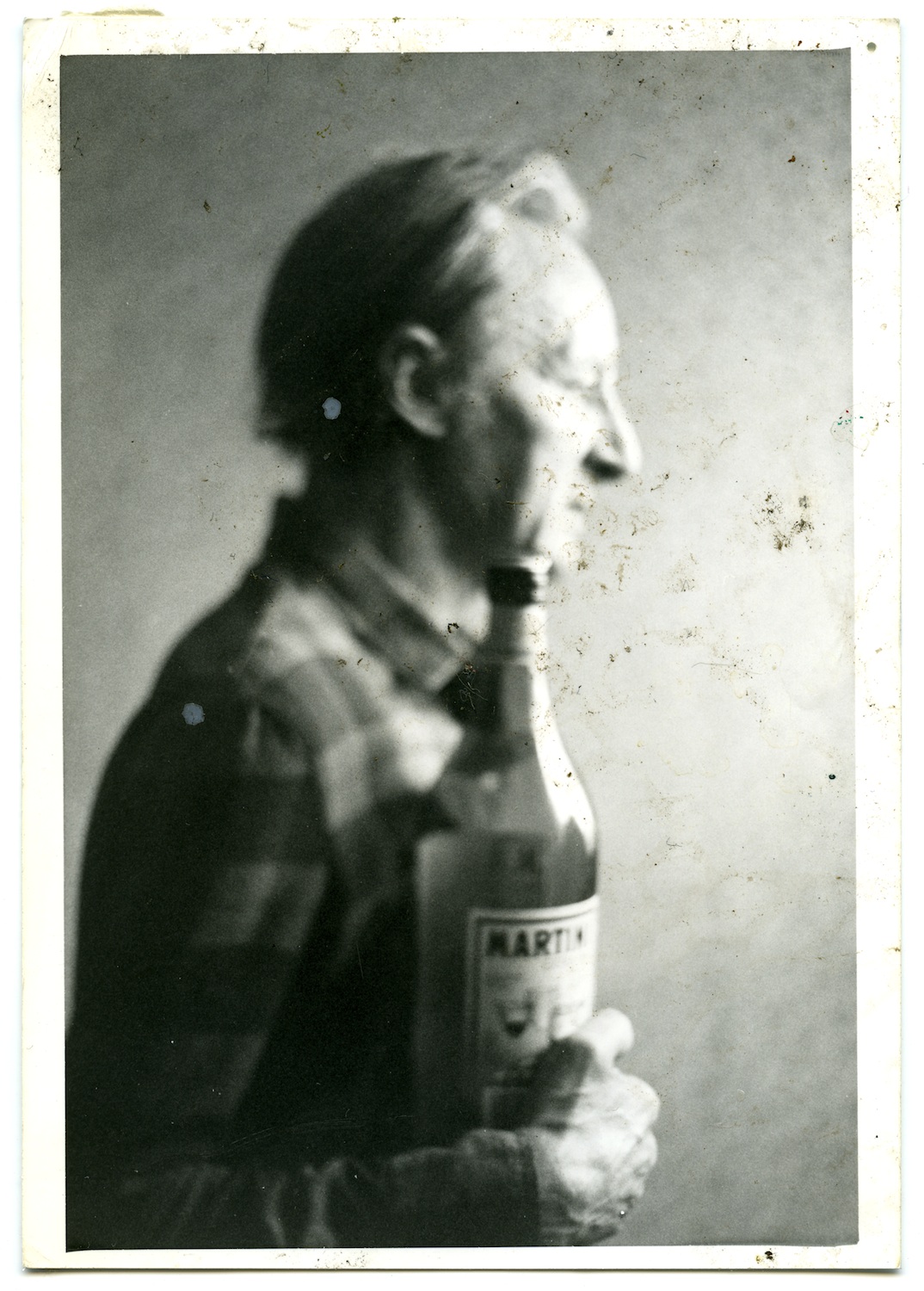

RB There was just me and my dad living in the flat in a tower block. My mum had left and lived in a neighboring tower block due to his incessant drinking. I saw this scene every day – he would be in his bedroom, lying on the bed or sitting on the edge of the bed, looking in the mirror, drinking. I thought that I would like to make some paintings about this tragic situation and the way he appeared to me in the bedroom. Whenever I made a painting I would make it quickly – each painting at the time took about 15-20 minutes. I did try to teach myself to take longer over a painting but the trouble was that my dad wouldn’t sit still for long enough – he’d want a drink or he would go to the toilet. Later I managed to get a 35mm Zenith camera. I thought I could use the photographs as source material for the paintings. He was held still by the photographs and I could paint from them taking more time.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

GM How did they continue from there to taking the rest of your family – your mother, your brother and the pets?

RB The first time I went back to the flat after I had left to go to University up north I found my dad wasn’t living there any more. The flat was empty and he was living in the new flat with my mum in the other nearby tower block. The way the flat was decorated was different from that of the flat that I grew up in. It was more opulent and there were more cats and dogs and small animals in cages everywhere – it was raucous.

GM So, while you were studying painting at Sunderland, Julian Germaine and [Michael Collins] the then editor of the Sunday Telegraph magazine saw some of the photographs.

RB Yes. When they took interest in them I didn’t think they were as special as they later became. I thought they were just interested in them through curiosity. The Telegraph editor came to my student digs in Sunderland and said ‘I want to see more of these photographs’, so I gave him a carrier bag full and he went off with them.

GM He was Picture Editor at the Telegraph Magazine at the time. Didn’t you see that as a bit odd?

RB I didn’t know that this could end in them being shown in galleries. I didn’t know you could show photographs in galleries at that time.

GM Did you start to appreciate them as solely photographs when Julian Germain and [Collins] the Telegraph editor started taking an interest.

RB No, the intention was still to paint from them. I was also interested in taking some of them just for the sake of taking them, as I did enjoy doing it and enjoyed seeing what they looked like when they came out.

GM. Would you consider them as accidental art then?

RB Maybe – in the sense that I did them for reasons other than being hung in galleries. But that happens a lot.

GM I just want to know how this change happened for you. You had the intention of becoming a painter and you were seemingly shoehorned into this photography role. Usually people make that decision before they start making work in the new medium.

RB I had this opportunity to publish about 50 of them in a book, I wasn’t sure about doing it because I didn’t want to be classed as a photographer – I didn’t want to be pigeonholed. I wanted to be an artist. I talked to a friend from Sunderland, and he said ‘you might as well do the book. Francis Bacon was a furniture designer before he became an artist… if you do the book of photographs, well, photography is closer to painting than furniture design’. So that swung it. But I was reluctant at first.

GM I suppose part of that reluctance was that these were very personal?

RB That never bothered me really. Why should it?

GM I would think twice about displaying my family.

RB Maybe you had closer ties with them? I don’t owe them anything and I never thought they would be shown in a gallery at that stage anyway. I thought they would be in a book and it would have a specialist market and not really a wide audience.

GM So the attention came as a bit of a shock.

RB Yes it did.

GM When was the edit for Ray’s a Laugh made?

RB Well, not straight away. It wasn’t until 1996 that we made the edit.

On a few occasions before then I looked through the Telegraph editor’s collection of photobooks, so I did become aware of contemporary photography from 1994 onwards. The later pictures for the book (1994-95) were being taken with this added awareness.

GM So some of the later images were being made with the knowledge that they were going to be used as photographs.

RB No, but they were taken having seen other photographers work.

GM Were they still being taken as basis for paintings?

RB Not necessarily. I’d never looked at photography books before 1994. I saw Larry Clark’s book, Tulsa, and I was amazed at the potential of photography. I could see that my photography could do more than I thought and it gave me confidence to continue.

GM To take these photographs as photographs, rather than as raw material for something else?

RB Yes, that’s one way of putting it. Before looking at contemporary photography I was getting my compositional ideas from painting but after I’d looked at the work of other photographers I think I was also getting inspiration and visual ideas from them – whether consciously or unconsciously.

GM. After you started being influenced by the work of other photographers, did you identify yourself as a potential photographer?

RB Yes I think so from 1994 onwards – maybe a little bit later.

GM So how many pictures in Ray’s a Laugh are taken from that perspective?

RB About half.

GM Can you see a difference and, if so, which approach do you think is more successful?

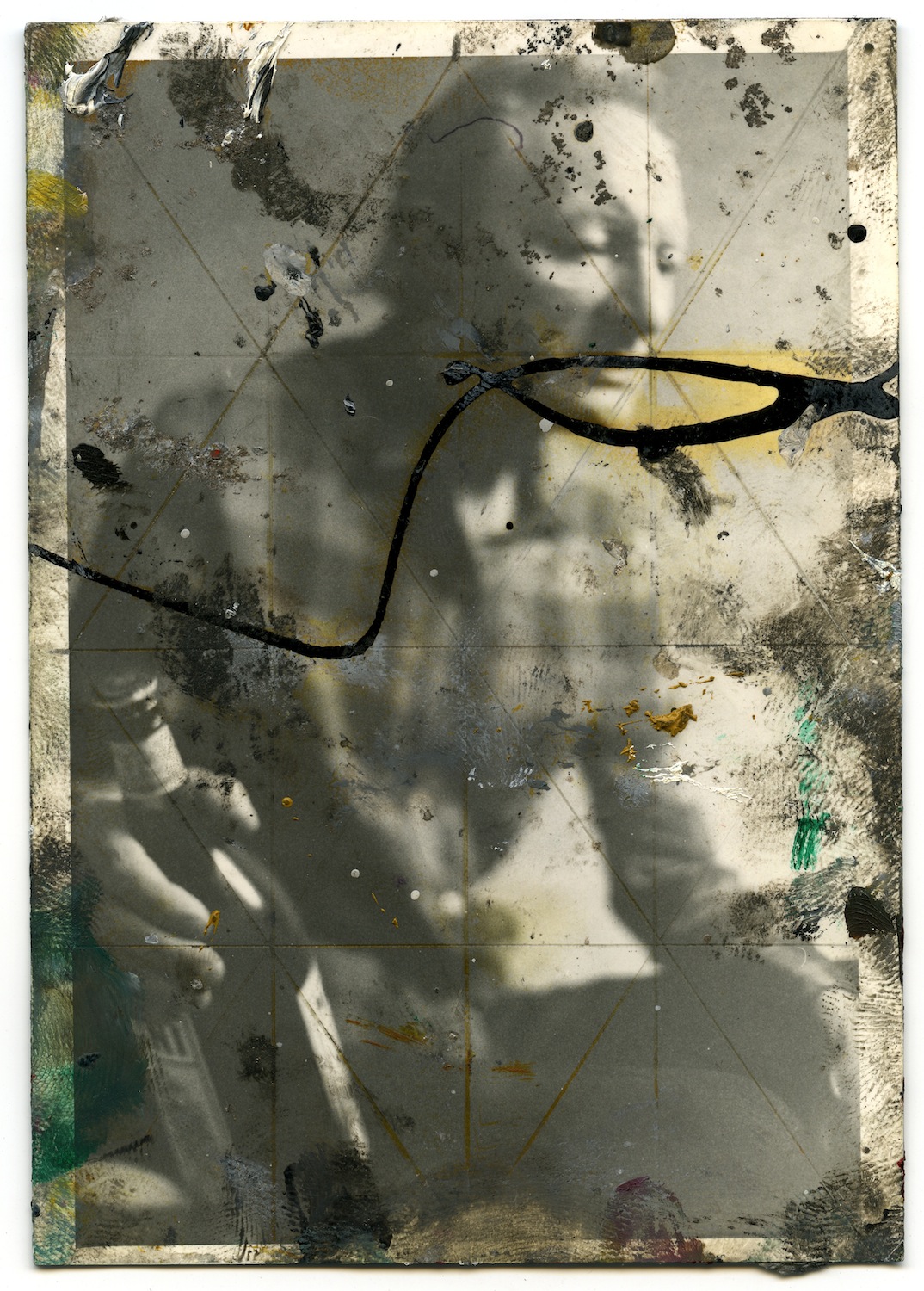

RB There is a very obvious difference to me. I prefer the more innocent ones I did before I’d seen the photo books even though they’re probably harder work for the viewer. However, in the later works I still didn’t want a polished aesthetic (I still had a snobbish attitude to photography). I thought that the technical mistakes I’d made could initiate better ideas for paintings and I wanted to continue that. Many of those ‘accidents’ where allowed to happen: they look like accidents but most of them aren’t.

GM So you were deliberately creating a snapshot aesthetic?

RB I was messing up on purpose but with the aim to try and make a better or more original image.

GM Why did you hang on to that snapshot aesthetic?

RB I wasn’t worried about the accidents then, or how they were read, because I thought they might make better paintings and I still wanted to be a painter.

GM But with the later one you made the decision to use them as photographs from the outset.

RB Its not like I am never going to make paintings out of them. I still might.

GM When the pictures had been spotted as interesting, they were brought together to become Ray’s a Laugh, which, to me, reads as a narrative about your dad’s addiction to alcohol.

RB My dad’s the main character in it, but it’s not all about his addiction or him being drunk. How many photographs are there where he is drinking? Lets look at the book. You see he’s not drinking there…

GM But he is drunk.

RB How do you know he’s drunk?

GM He’s got a nosebleed and he can’t stand up.

RB That’s one, two…

GM He is drunk in that one.

RB Yes but there’s no beer.

GM He’s certainly been drinking

RB There is a bottle there – shall I say four for that?

GM But the ones of him drinking are so powerful, and the book is called Ray’s a Laugh.

RB Five, six – he’s not drinking there – seven.

It’s like if you look at Wolfgang Tillmans’ work. Some might say a lot of it is all about penises. But if you count the number of penises in photographs in a show or book of his you would probably only actually see two or three depicted.

GM Are you saying that Ray’s addiction was not what your pictures were about when you were taking them?

RB I did want to make images of the tragedy of the situation. I wanted them to be emotionally very moving. I don’t think I concentrated on the drinking but on the effects of it. I didn’t want to illustrate alcoholism or make a documentary about it.

GM I wonder how it got pared down to that edit? Did you and the editors sit down together?

RB I probably picked out 70- 100 of my favorites and they did a final edit of 50 or so images.

GM Did you agree with the edit?

RB At that time yes. There are a few I wouldn’t include if I re-did it now. The TV dinner, for example, looks like the sort of image that any hack-photographer could have come into the flat and taken. A picture like that has the threat of undermining the rest. But there are only a few I would take out or swap for others.

GM This book put your life and your family into the public realm.

RB Well, I hadn’t lived with them since 1991.

GM It’s still your life though – you were there when the photographs were taken.

RB They’re my parents and my brother. It’s not like I was photographing the inside of my own flat.

GM No, you were photographing theirs.

RB So it’s their lives rather than mine.

GM After Ray’s a Laugh, you came to a point where you had to make another piece of work and to move your career along.

RB Yes, in 1997 I made a series of urban landscapes that ended up being published in a book called Black Country (2004). I still wanted to make snapshots but I wanted a different subject – I wanted the images to be as good as the previous ones but minus the sensational subject matter of Ray’s a Laugh.

GM Why did you want that?

RB Just to see if I could make photographs without any sensational subject matter. I needed a really mundane subject, so I chose to photograph the area I was born and grew up in. I wanted to take photographs of the space. I didn’t want any image to be a portrait, a picture of the sky or a car or a building, because then it would be about the subject matter. I wanted to concentrate on the spaces only.

GM This project then moves from the snapshot style of your earlier work into medium format with more polished images. What made you change your working method?

RB I wanted to let go. I didn’t want to make innocent snapshot photographs for the rest of my life. I wanted to learn to make a photograph I had to think about first.

GM So why not revert to painting?

RB I was too lazy to make paintings by then and still am. I am no longer prepared to spend weeks at a time on a single painting when I can make a picture in a fraction of a second. I thought it would take less time to learn how to make this other type of photography. Also, there are so many different types of photograph you can take in the world why limit oneself to making one type? Some photographers seem to stick with one type but I get bored doing that.

GM So you were training yourself technically?

RB Not technically. I was forcing myself to preconceive my photographs so they would not be snapshots.

GM Was this a part of you losing your naivety about photography?

RB Yes, naivety or innocence. I thought why not just lose it altogether instead of holding on to it in the hope it will allow me to continue to take spontaneous photographs.I have always been interested in landscape, so I started photographing landscapes using this new method.

GM Do you think, looking at The Black Country publication, that the second half of the book is as successful as the first section of snapshots?

RB I think the later ones are more sumptuous, but if you take the colour away there’s not much there. If you take the colour away from the snapshots the structure and the balance is still there. So I tend to think that the snapshots are probably better pictures spatially.

GM Regarding your most recent project Zoo, you have made three very distinct set of images – a series of video pieces, some medium format studies and a series of snapshots based on your mothers pictures of zoo animals. Why have you returned to the snapshot style and the family for this work?

RB It’s a bit of a story. My mother died recently and I had the responsibility of clearing out the empty flat. One of the few things I kept was the family albums. A moving thing about them was the way she had included snapshots of zoo animals amongst family portraits. Her zoo snaps are very childlike. They are mostly taken on 110 and 126 film which makes them blurry. They have been taken very innocently, as if she was unaware of the absurdity of the captive animals predicament. I suppose the intention was to record happy days out.

GM But why reflect on your mum’s album?

RB I had been making these really considered, medium format photographs in zoos and I thought it would be a good antidote to that. I decided that I wanted to make a group of animal pictures inspired by them. It is another way of seeing zoo animals and its how a lot of the public must see them.

GM Did the project need an antidote?

RB The project needed more variety and this was another approach to representing captive animals. I always stood where a spectator would and never went behind the scenes because I wanted to do it through the spectators eyes. Ther is a bit of the spectator and a bit of my aesthetic in them.

GM This work seems to hark back to the family work a bit – not just technically but also conceptually. The idea of someone trapped in a situation – like the gorilla or Ray.

RB It goes back to, I guess, when I was trying to paint Ray as a figure in an interior.

GM But also the idea of someone or something trapped in a situation?

RB I wanted them to have the look of something being contained. I wasn’t thinking of any relationship between the zoo and family work, but it is there. With the zoo snaps I’m imitating the look and feel of my mother’s photographs. She’s taken hers innocently and compositionally mine are better, but they have the same look. I deliberately used disposal cameras and cheap cameras in Ray’s a Laugh and I did the same with the Zoo snaps.

GM Most recently you have started making photographs including your own partner and child – using the cheap cameras and look of Ray’s a Laugh or the snapshot photographs from the Zoo series.

RB Yes, I think the baby was born at the same time I decided to take the Zoo snapshots. When the baby was born I took pictures of him for my own family album so we would have a record of him growing up- just as most people would do. When I got my piles of pictures back from the Zoo trips there’d be baby pictures mixed in and I’d separate them out. I saw that some of the baby ones had the same aesthetic of the zoo snaps probably because that was what I was working on at the time. It wasn’t a plan to start photographing the baby but when I saw that they were working pictorially I decided to continue with them in earnest.

GM There are also pictures in the series of your son with your father, Ray, and brother, Jason, taken in that snapshot way, which seem to draw this new project and Ray’s a Laugh together.

RB I took the baby to see Ray recently in the nursing home because he might die soon – he is very old. I wanted to be able to show Walter in the future that I took him to see Ray before he died. Walter would have something of him and his grand dad to look at even though he won’t remember meeting Ray. The pictures of Ray, Jason and Walter do draw the two bodies of work together or even helps to make them one project.

GM There is something of a theme of making the personal public running through Ray’s a Laugh, Zoo and this latest work.

RB That’s never bothered me. I guess a lot of people wouldn’t want to do that but if you’re an artist you have to take risks. When I was a primary school kid I didn’t want any of the other kids to see where we lived because we were poor and the place was not cared for. We didn’t have any heating or hot water, the carpets were dirty, there was dog shit everywhere and there was no paper on the walls. I don’t know when the turning point was but at some point – perhaps when I first started to photograph Ray in his room- I decided never to think about hiding my background or upbringing anymore. It was easier, less stressful, not to bother about it. Why should I hide my poor background anyway?

GM I wonder if the snapshot aesthetic is something you are going to keep on using? It has become a signature style.

RB I’ve been thinking about signature styles. As I said before there are so many different types photographs you can take. A signature style is usually good for marketing the work as everyone can immediately recognize it. I don’t intend to stick to one style or way of taking pictures although it would make financial sense.

[/ms-protect-content]

Published in Photoworks Annual Issue 8, 2007

Commissioned by Photoworks