When Tate Modern presented the huge survey show Street & Studio back in 2008, one striking conclusion seemed to emerge from its teeming presentation of hundreds of photos by dozens of photographers. Distinctions between the street and studio are becoming less clear; or rather, they were never as clear for photography as the show’s mischievous title implied.

The Scene of Photography and the Future of its Illusion

In the 1930s Bill Brandt was selecting locations and recruiting models to make ‘near documentary’ images long before today’s staged tableaux photographers, while Helmar Lerski was shooting studio portraits that mimicked naturally refracted daylight. Philip-Lorca diCorcia can now shoot street portraits with all the rhetorical artifice associated with a multi-flash studio rig. Jeff Wall can rebuild a nightclub in his studio when the real one he is photographing closes down unexpectedly.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

The restrictions of both street and studio are there to be overcome, and for a range of reasons – aesthetic, practical, philosophical – much photographic practice prefers increasingly to ignore the distinction altogether. Now that lights are so portable and digital post-production has become at least as significant as pre-shoot planning, much of the palaver that kept the photo studio rooted in bricks and mortar has been overcome. The studio can be anywhere you want it to be. Well, nearly. Even if the facilities offered by a well-appointed studio seem less of a necessity that they once did, such spaces do still exist and they are needed. But it may well be a weakening of the necessity that has attracted a number of photographers to turn their cameras upon the studio and reflect upon what it actually is.

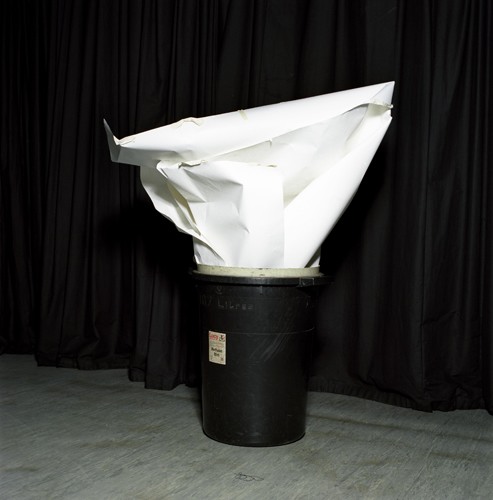

The studies of studio environments and equipment by Harry Watts, along with Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin’s shots of white backgrounds, conjure up the pre-theatrical void and limitless potential of images past and future, picturing the spaces in which photographs have been and will be made. There is still plenty to look at on these stripped stages of marked floors, electrical cables and de-featured surfaces, but they allude inevitably to what is not there and signal the idea of the ‘degree zero’ of the photograph – its point or place of origin. Whether such a thing exists as anything more than a theoretical abstraction is another matter, as is the question of whether that degree zero might be located elsewhere, perhaps in the camera, the darkroom, on paper, screen or even on the human retina. These photographs conjure that conceptual netherworld between the prosaic, material facts of images and what so many contemporary philosophers refer to as ‘the image’, a nebulous, immaterial idea.

We might be tempted to make a parallel with that age-old subgenre of art in which the painter paints their own studio, producing an image of the scene of its own making. But ‘studio’ tends to mean something quite different for photographers. It is not a space permitted to fill up with the cast-offs of their art, the way painters might casually discard failed canvases, swatches of colour, preliminary studies and the like (although there are photographers who do inhabit their studios this way). Generally speaking, the photographic studio is a space to be kept clean and sparse, returned to neutral after the image-making has been done, particularly if it is has been hired for the shoot. Perhaps the comparison should be with the blank canvas. In picturing the studio space the photographer confronts at some level a tabula rasa.

It is worth noting here just what status the monochrome and the blank image have for photographers. Or do not have, since they mark a direction few have been willing to take or even recognize. For a contemporary painter the blank canvas and the monochrome loom very large on their horizon of possibility. Once the blank canvas was accepted as an artistic gesture and a legitimate work of art, every painting thereafter would be a painting on a painting. Even a painted monochrome is a painting on a painting. While a similar condition does exist for photography (for example, in the form of the unexposed/overexposed negative or the monochrome made by a variety of possible means) its profound implications have barely made a dent on the understanding of the medium hitherto. Indeed, photography has had a rather repressed relation to its founding blankness. Consider what it would it mean if the first exercise for students of photography was to make a print from an unexposed negative and then one from a totally overexposed negative (assuming they still shoot on film and print in a darkroom). Would this be no more than a perverse exercise, a pedantic hoop to jump through, or would it ground an understanding of photography upon something else, something set apart from the weighty presumptions of realism? Could the monochrome figure as meaningfully for photography as it does for painting?

There is a parallel to be drawn between the photographing of the studio space and the recent revival of interest in what is limitedly labelled ‘abstract photography’ – those images that seem to be recognizably photographic without having a recognizable referent or subject. I am thinking here of certain works by Wolfgang Tillmans, James Welling, Lisa Oppenheim and Walead Beshty, but there are many others. Both the image of the studio and the abstract photograph constitute gestures that may strike the viewer as simultaneously a filling-up and an emptying-out of the photographic act, and even as symptoms of a moment of heightened awareness of the fragility of the medium as it mutates from one form to another, or heads toward dissolution or even obsolescence.

Perhaps too this photography is echoing here the historical fate of painting. Finding itself in a new visual culture and artistic order defined at least in part through the growing ubiquity of the photographic image, painting was forced to look inward in order to find the courage to reinvent itself. Tenuous or not, it’s a line of thought that is instructive not least because it might steer us away from the temptation to read these images as pre-emptive obituaries for photography. Mediums do not really disappear or die, especially in the context of art, but their status and significance as art is often conditional upon their broader status beyond art. The present security of photography’s place in contemporary art seems inseparable from its insecure status outside.

Broomberg & Chanarin’s images of what are known in the advertising and portrait business as cycloramas show the white walls and floors joined by seamless curved cornicing that provide the most adaptable arena for the widest variety of studio photography. As staunch allegorists, they have titled this series American Landscapes, and their website blurb suggests we see these spaces as the ‘scenography for a free market economy’. Where the real space of the American west was once also the imaginary space of the nation’s ideological projection, so the commercial studio came to assume a similar role in the virtualised era of image spectacle, they tell us. That’s an interesting take, certainly, but the fact that the duo are minded to put it forward themselves shows just how fragile the meaning of such images can be. There’s nothing in these photographs that can secure this reading, or any other. The industries of American fantasy, notably advertising and Hollywood cinema, have been inviting us behind the scenes and showing us the machinery for almost as long as they have been in business. Part of the appeal of fantasy, as any Freudian will tell you, is knowing very well that it is fantasy. It is not as if the whole edifice comes tumbling down once you get a glimpse of the scaffolding. Even if these photos propose a ‘laying bare of the support structure’, what is really laid bare is that facts do not speak for themselves: they still require interpretation, however stripped back they seem. Allegories are by their nature unstable, however securely we may wish to hold them in place. ‘American Landscapes’ sounds like a plausible title for an advertising company or a commercial post-production studio. If Broomberg & Chanarin’s images cannot be easily co-opted into looking like adverts for the advertising industry it is only because they are a little dirtier than would be preferred. The precarious criticality of the series hinges on the foregrounding of wear and tear – the scratches and scuffs that would be otherwise conjured away by Photoshop.

A different version of all this can be found in the ongoing series of colour photograms James Welling has been making since 1985, known as Degradés. They are made in the darkroom simply by adjusting the enlarger’s colour filtration and producing a unique impression on C-type paper. While Welling’s procedure has remained admirably consistent for a quarter of a century, it has gone from looking state of the art in the pre-digital 1980s to a specialized craft in 2010. The shift is made starker still once we know this was the procedure once used to make bespoke colour backgrounds for shooting still lifes and portraits (simply dial in your colours and make a large colour field print). The Degradés once turned photography’s background depth into its foreground flatness. Now they seem more about holding onto something material in the face of virtualization. But none of these ‘meanings’ are particularly secure.

In her series 80 Hours Roberta Mataityte has photographed the matt black interiors of darkrooms – the revolving doors; the heavy curtains and printing cubicles; the walls marked by sightless groping with high precision machinery. The title refers to the total time spent on the project. We presume the series was shot and produced in the very kinds of space it depicts. At first glance it is difficult to tell if it is the photographs or the scenes that are black and white. Photographic printing is by its nature a ‘dark art’ and Mataitiyte’s prints are as sinister as they are banal (with the grubby theatre we might expect from forensic photos of an S&M club). But are these photos responses to a space that feels totally familiar, documents of a space that is strange, or records of a space whose days might be numbered?

Back in 1971 John Hilliard produced a piece entitled Camera Recording its Own Condition (7 Apertures, 10 Speeds, 2 Mirrors). He pointed his 35mm SLR at a mirror and took shots at every possible aperture and shutter speed setting. The resulting photos were arranged in a grid in which only a diagonal line of prints appears ‘correct’ while the opposite corners are complete white and complete black. Back then it seemed like the ultimate self-reflexive, reductivist gesture. But what should we make of the fitful but significant works subsequent photographers and artists have been making in that direction for the last forty years? Attempting to record and reflect upon photography by means of foregrounding its apparatus can produce any number of artworks, all quite different in approach and character. It suggests that photography’s ‘own condition’ is not as easy to reduce or define as it may seem. And beyond images of studios, darkrooms, cameras and the exploration of abstraction, might we still need to accept that every photograph ever taken cannot help but record its own condition?

[/ms-protect-content]

Published in Photoworks issue 14, 2010

Commissioned by Photoworks