Its two o’clock in the morning and I’m sitting with a mug of milk at a laptop with a broadband connection in our upstairs middle bedroom alternating between writing this magazine article and waiting to bid for a magazine on eBay.

The middle bedroom is the most indeterminate space in our house and struggles to function variously as an office, spare bedroom and transit room. It’s cluttered with washed up domestic debris awaiting dispersal to the attic, the charity shop or the recycling centre; holiday luggage, boxes of Christmas decorations and the sloughed off snake skins of outgrown children’s cloths and abandoned toys. To get near the desk I have to first pick my way past a little tikes truck™, a tub of Duplo and a pile of Gap tops and Oshkosh dungarees.

This is the very stuff of eBay, the endless unwanted items that sellers around the world are trying to pass off and turn into cash and that buyers are keen to snap up at bargain prices. EBay proclaims itself to be ‘an online person-to person trading community on the Internet’ and since its first inception in San Jose in 1995 has recruited senior management figures with experience in developing the brand identities of companies such as Hasbro, PepsiCo and Disney. By 2000 eBay had over 22 million registered users and has since secured an 80 percent share of the global person to person online trading market with sites in North America, Europe and Asia. It models itself on the American yard sale at which, on an agreed day, neighbours would put out for sale the surplus contents of their attics, basements, garages and spare bedrooms. The language of the self regulated community is firmly embedded within its business practices and corporate image.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

By charging an insertion fee, additional listing option fees and a final value charge of between 1.25% and 5% of the end sale price eBay is on target to earn $3billion a year by 2005. Assuming an average profit of 3% on each sale the rough calculations suggest that eBay has the capacity to carry $90billion dollars of consumer traffic a year. In July 2002 eBay acquired the online payments company Pay Pal, described by analysts Merrill Lynch as the ‘gorilla in the jungle’ in a deal valued at $1.5 billion dollars. eBay has rapidly become a colossal, global, corporate player and with such a dominant market share is already anxiously looking over its shoulders for the threat of anti-trust actions in the United States.

But it’s not just the ordinary and everyday that is up for grabs. eBay is the hunting ground for specialist collectors with niche interests. The banal keeps good company with the surreal. For $29,500 you could have recently made an opening bid on a metal alloy, 80cm diameter 1950’s sputnik with two 3m and two 1.5m whip antennae. To the odd should be added the distasteful. Just last year, within hours of the space shuttle Columbia’s disintegration on re-entry, still smouldering debris from the disaster was being offered for auction. EBay responded by flushing out the offending items, but within days a further 3000 listings of Columbia related memorabilia were appearing, from plastic modelling kits to heat tiles first sold off after Columbia’s maiden flight. The incident revealed a great deal about the mawkish and opportunistic tensions that tear away within the troubled American psyche.

British culture is not, somehow immune and I’m sure we’re all familiar with the story of the English seller who offered his kidney for auction. It was of course affixed in its rightful place at the time of the sale, the eventual buyer having to arrange flights to an appointed hospital of their choosing: the kidney wouldn’t simply arrive in a thermos box sent out by FedEx. For the would be Frankenstein eager to construct a modern day monster in the garden shed, eBay offers a tantalising assemblage of body parts of differing pedigree; a hank of freshly cut human hair, artificial limbs, false teeth and the finger nails of a serial killer (signed) have been all been offered for sale at one time or another.

The item I’m waiting upon from a seller in New Jersey, who seems to be attracting no other interested bidders, and could therefore be mine for as little as $3.50, is the November 1947 edition of Fortune magazine. I’ve a particular interest in the history of editorial photography and Fortune is the Capitalist counterpart to the seminal Soviet magazine of the Stalinist era, USSR in Construction (also occasionally available on eBay but at a far higher price. I’ve so far bought just two) . Henry R.Luce founded Fortune magazine in February 1930 with aspirations to create an experiment in the possibilities of high quality magazine production that would transcend its more prosaic function as a business bulletin. Fortune was expensive to produce and was run as the flag ship title amongst a roster of Luce’s more profitable publications. It editors attracted many of the leading writers, artists, illustrators and photographers of the age. The production values were high and the photographs, in common with USSR in Construction, were reproduced as sheet fed gravures rather than through the cheaper half tone print process. Margaret Bourke White and Erich Saloman were early contributors and between 1934 and 1941 Walker Evans accepted several freelance assignments before being employed as a staff photographer from 1945 to 1965. In all, the magazine published 372 of his photographs.

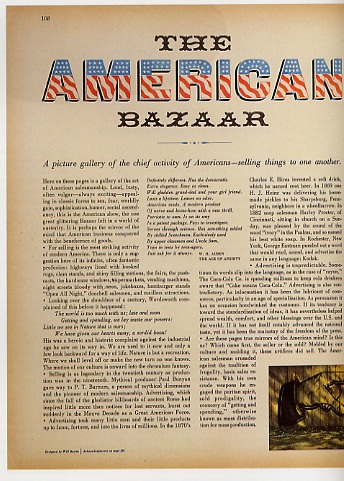

Evans’s career at Fortune was authoritatively researched for an exhibition at Wellesley College Massachusetts in 1978 and the accompanying catalogue not only provides a useful history but an indispensable shopping guide. From recent trawls through eBay I’ve bought several of the key editions containing key Evans portfolios: Chicago: A Camera Exploration (1947), One Newspaper Town(1947) and Beauties of the Common Tool (1955). I’m now in pursuit of the editions which featured just one or two of his photographs. November 1947 is a particularly interesting one and it’s apposite that I should be buying it off eBay. It features just 3 tinted photographs by Evans lurking within a lavishly illustrated and wildly coloured, 14 page feature entitled The American Bazaar – A Picture Gallery of the Chief Activity of Americans- Selling Things to One Another. The story is in celebration of the popular art of advertising and is themed under headings such as ‘Assault on the Senses’ and ‘The Aural Nerve. ’. It was art directed by the German born Will Burtin who together with the likes of Alexey Brodovitch at Harper’s Bazarr brought a new spirit of European modernity to the American magazine. The cover designs for Fortune, by those émigrés all, Francis Brennan, Peter Piening, Will Burtin and Walter Allner still appear as breathtakingly contemporary; so much so that you have to do a double take on the cover date. The magazine must have looked very handsome to the Brook Brothers suited businessman, flipping through them as they waited for an appointment, sunk into a Barcelona chair, beneath a Jackson Pollock canvas, in the glass and marble lobby of a Mies van der Rohe office block.

Evans had more than a passing interest in the advertising signage that illustrated the Fortune piece. He recognised it as important and vanishing form of folk art made all the more interesting when it was weathered and frayed. His practice as a photographer, in hunting and gathering the evidence of a decaying and vanishing America, was paralleled with his collecting of the shop and street signage and metal advertising plates that he assiduously bought, salvaged and occasionally liberated throughout his career. His collecting impulse extended to turn of the century American postcards and twenty six lithographed postcards from his collection were published in various editions of Fortune. Evans bought many of these at the eponymous American yard sales

For the humble trader wishing to open up for business on eBay the key tools are a computer with an internet connection, an optional flat bed scanner and a digital camera. The shop window for eBay is essentially photographic. Unlike a conventional market at which a prospective buyer would pick up and examine an object, as if squeezing and sniffing the fruit, eBay’s buyers rely on digital pictures and the vendor’s description. These visual and written descriptions demand close scrutiny. Seller’s openly apologise for the quality of their images and there are times when it’s unclear just what it is that’s for sale, with the proffered item buried somewhere in a chaotic image. Real life frequently intrudes as children, pets and the detritus of domestic disorder appear at the frayed edges of the frame. There are improbably bizarre tableaux and naïve but artful still lives that invite speculative pyscoanylital readings. All of this is of course open season for the modern day archivist and the part time cultural commentator. Toronto based Bruce Mau Design Studio produced a conceptual design installation of 1,000 images downloaded from eBay that were presented as ‘a topology of desire’ to be exhibited in 2000 at that temple of the eccentric and eclectic collector, the Sir John Soane Museum, London. The work was subsequently published in the Alphabet City edition, Lost in the Archive. The images had been stripped of their accompanying text and bid value and acted alone as mute archaeological fragments as if discovered from a strange and lost civilization.

John D. Freyer’s 2002 publication, All My Life for Sale, is derived from a very different eBay project and pursues an almost opposite tact in which every object is invested with a history and a future life. A recent graduate from a college in Iowa, Fryer had decided to abandon his teaching job and return to New York. He began to sell items on eBay and soon became so seduced by the process of photographing, describing and tagging that he set up a website to provide a complete inventory of his every possession. Through a process of attrition he settled on the domain name allmylifeforsale.com and so began the next phase of the project , the life-clearance sale of each of the items on eBay. His clothes, books, magazines, furniture were all offered up together with the contents of his refrigerator and medicine cabinet including a half bottle of mouthwash and a packet of Porky’s BBQ Pork Skins, bought for $1 by a buyer in Tokyo. To these were added the Christmas presents he’d wrapped and labelled for his family. Rather graciously his step-mother acted for the family, buying up their gifts and fighting off last minute rival bids from random strangers. With everything sold Freyer reinvested the money in a road journey across America to revisit his former possessions in their new homes. On September 10 2001 he reached New York when the tone of the project changed, and as he describes it, ‘I stopped caring so much about the objects and started caring more about the people who invited me.’ Underpinning the project, and what makes it so intriguing, is the knowledge that Freyer had originally graduated in political science having written a thesis on the use of customer profiling in business and government surveillance. His obsessive inventory of used, soiled and half eaten items somehow seems to knowingly subvert the corporate thirst for mapping patterns of consumption and stalking their customers.

The internet itself has a dishonourable history of attracting knowing subversives, although it is hard not to be charmed by the sexual exhibitionists who have risen to the challenge of eBay’s more puritan ethic. At an early stage in the development of their business model the owners of eBay realised that internet retailing had a tendency to slide inexorably towards pornography. Quite sensibly and in order to preserve the more homely feel of the community marketplace the company decided to exclude images of a ‘sexually explicit nature.’ The recent acquisition of Paypal has further hardened attitudes with the prohibition of the service for even the most anodyne copies of vintage 1950s Playboy magazine. In order to slip under the radar, a hard core group of dedicated pornographers have taken to smuggling in images of their own private performances. And so it is that if you were to innocently search for an electrical kitchen appliance you might find, within the listings, references to hot toasters and steamy kettles. Open the item to inspect it, enlarge the image and there, in the reflective surface of the polished chrome, is an all too clear picture of a couple enjoying a breakfast time sexual liaison.

My own interests in eBay are altogether more prosaic. The inexorable rise of all things digital is steadily pushing chemical based photography towards the quite backwaters of heritage media. eBay affords the opportunity to lucky dip into the back catalogue of photography’s legacy and pull out the plums of the books and magazines that bear the first published works by some of the masters of the media together with the oddities of the spectacular vernacular. For those of us who work with photography in museums and galleries or teach in higher education, these fast track bargain hunts can provide the vital, secondary, ephemeral material that can put flesh on the dry bones of a lecture or add thoughtful context to an exhibition. Walter Benjamin’s 1937 essay, Eduard Fuchs, Collector and Historian explored the differences and possibilities of the independent collector, free from institutional restraint, to follow their own, self directed, agendas. Benjamin quotes Fuchs’ distain for museums who, due to the limitations of space concentrated on assembling the showpieces. ‘But this does not alter the fact,’ wrote Fuchs, ‘that because of it we get only a very imperfect conception of the culture of the past. We see it dressed up in its Sunday best, and only very rarely in its most shabby workaday clothes.’

Benjamin councils against the inherent dangers of collectors developing a fetish for the precious object. The surface scratches, blemishes and discolorations that mark photographic prints can act as traces of their functionality but also inspire more visceral pleasures in the dedicated collector. I was interested to visit a recent exhibition of photographs in London that were destined for auction in New York. I was particularly attracted to the original art director’s page proofs for the 1976 edition of Rolling Stone magazine which was almost entirely composed of Richard Avedon’s, black and white portraits of the movers and shakers of American society. It was during the shoot for this issue that Henry Kissinger rather implausibly appealed to Avedon to ‘be kind’. The edition marked the magazine’s move from San Francisco to new offices in Manhattan and Avedon’s portraits heralded the literal and figurative embrace of ‘the suits’. The 10x 8 proof prints of the likes of Jimmy Carter and George Bush were held in place by paper clips with the texts cut and glued to the page. These were over-laid with china graph scrawled notes such as ‘ Drop picture, Avedon will re-shoot Ethel Kennedy tomorrow and substitute.’ As I absorbed the work it was explained to me that the original paper clips had been replaced but had been kept for the eventual buyer. The piece sold for $150,000 setting a new record price for a work by Avedon and when, out of curiosity, I down-loaded the auction results I couldn’t help but imagine the pleasure of the buyer when they collected their prints to receive, as an additional bonus, a small commemorative box of rusted paper clips.

I found the perfect antidote to these fetishistic and avaricious desires at a lecture by Tariq Ali. I’d organised an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, Circling the Square, that mapped the parallel histories of photography and Trafalgar Square and had invited Tariq Ali to publicly reflect on the history of political dissent in the Square. At one point he recalled how, in 1968, at the height of the anti-Vietnam movement, and as editor of the radical magazine Black Dwarf, he had received from Mick Jagger an early hand written draft of the lyrics of Street Fighting Man. ‘I copy-typed the words into the magazine and then screwed up the original and threw it into the bin.’, Tariq Ali recalled, emphasising the anecdote with a theatrical hand gesture. I could detect a glint in his eye as the dedicated anti- materialist absorbed the shudders of the all the little eBayers assembled in the audience. And in that moment of self recognition I laughed out loud.

[/ms-protect-content]

Published in Photoworks Issue 2, 2004

Commissioned by Photoworks