What do Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Alexander von Humboldt, Edgar Allan Poe, Mark Twain, George Bernard Shaw, Rudyard Kipling, Gertrude Stein, Upton Sinclair, D. H. Lawrence, Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot have in common?

They were self-publishers. This list could be enlarged with an endless number of less prominent names, and I only mention them to disperse a common assumption, that self-publishing is an option for authors who are not good enough to be taken on by established publishers. Artists publishing their own books face a predicament: while self-publishing is often considered to be the confession of failure, the artist’s book itself seems to epitomize the perfectly autonomous, self-determined work.

For the authors mentioned above, the business of publishing a book was different to how it is today. Some of the problems and pitfalls are the same, however: principally, money (the lack of it) and the co-ordination of the various people involved. A complex process that involves an author, an editor, a designer, a publisher, and a printer (not to mention accountants, distributors and retailers) is close to a sure recipe for disaster. Quite often the ideas, ambitions and attitudes of these headstrong people turn out to be incompatible. Minimizing the risk of trouble or avoiding it altogether is one reason authors turn to self-publishing.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

The second reason is the problem of capacity. A limited number of publishers cannot accommodate the desires of a nearly unlimited number of authors. From the outsider’s point of view, a publishing house is a kind of slot machine. Authors put in proposals, manuscripts or dummy books into the machine and pull the handle. It starts to emit funny sounds, and after a while it either produces a book or it doesn’t. We don’t know what happens inside the apparatus; we’ll never know for sure why some books are winners while the majority of players draw blanks. For the disappointed authors, publishers, like arcade machines, can seem like ‘one-armed bandits’.

This brings us to the next reason: money. The machine designed to swallow authors’ ideas also has a slot for coins. It’s an open secret that in modern times proposals – in particular for art books – that are entered together with a cheque are more likely to win; the number of zeros on this cheque directly correlates with the probability of a proposal turning into a printed book. The artist or the gallery exhibiting the work is, in this arrangement, supposed to provide a substantial part of the budget, as many modern publishers eschew the financial risk of publishing. This is rather new, and it’s a development that, in German at least, turns the meanings of words on their head. In English, a ‘publisher’ is someone who makes something ‘public’. In my mother tongue, verlegen (to publish) is derived from vorlegen, which means to advance money. Interesting, isn’t it? Traditionally, the publisher is the one who comes up with a budget, the one who is able and willing to invest in ideas, to take a risk. Today, artists, dealers and museums have turned into sponsors of publishers and printers. It doesn’t take a genius to understand that, if you have to spend your own money to make your own book, you might as well bring the whole thing under your own control.

The importance of independence becomes clear if we look at an extreme form of self-publishing: samizdat, the voice of the opposition in a totalitarian society. The particularities of this underground movement are summarised by one of its main practitioners, Vladimir Bukovsky, in one sentence: ‘I myself create it, edit it, censor it, publish it, distribute it, and get imprisoned for it.’ Censorship may not be an issue in large parts of the world any more, but artists have to struggle with its more subtle sibling, that answers to the name of ‘mainstream’. The response, on the part of some authors, is called independent publishing.

No publisher ever offered to put out a book called One Picture containing a single image. Hans-Peter Feldmann published it, along with works by a number of similar misfits. Today, these poorly printed little booklets are considered seminal artist’s books, have been influential for a generation of artists, and are sought-after rare books. Nevertheless, you still don’t find a big publisher who would be willing to support a similar endeavour. There is a very limited number of prevailing book models, a fact that the superficial variety of designs does little to disguise.

Ed Ruscha’s Twenty-six Gasoline Stations and later books were published by the artist himself. Their impact was tremendous, and it is time to remind the growing group of book connoisseurs that Ruscha’s books were, and are, appreciated not because of the paper stock, the printing quality or the fine binding but because of the artist’s radically new editorial concept. The slot machine wouldn’t accept such an offering. A niche publisher of exquisite livres d’artiste wouldn’t accept it either. There was no other choice for Ruscha than to do it himself.

Despite the increasing number of small and very small publishing houses, self-publishing has become the obvious option for an increasing number of artists. This is mostly due to the fact that for more and more artists the book has become the work itself; it is no longer seen as a catalogue of photographs that have a life outside the book, in galleries, filing cabinets or frames hanging over collectors’ sofas. For this reason, exercising maximum control over the publication process, as Stephen Gill points out, is crucial. Finding the suitable material, technique, and form for each project, instead of doing things according to the publisher’s defaults, is one of the advantages of self-publishing.

Modern technology facilitates do-it-yourself approaches and at the same time do-it-yourself creates skill and experience. Many contemporary artists are skilled bookmakers with substantial knowledge in fields that traditionally required specialised technicians. Some artists – Morten Andersen, for example, who published nearly all of his books himself – started by making fanzines and slowly grew into this new field of activity. Artists who were educated in modern art schools’ media departments, rather than in the old school photography world, have a different vantage point already. They are used to working in a variety of techniques and media as well as being responsible for every aspect and every pixel of their work.

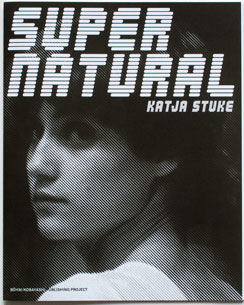

The crucial moment for most self-publishers – from Katja Stuke and Oliver Sieber with their ongoing Böhm/Kobayashi publishing project, to Erik Kessels whose books are produced by his agency as a part of a wider communication strategy, to young activists like Erik van der Weijde with his continous output of weird little books – is the strong desire to do things the way they want them to be done, and to do them at their own pace. They understood that nobody will be more enthusiastic about their books than the authors themselves, and they enjoy the flexibility of being able to make a book within one week if necessary, instead of waiting years for a publisher’s approval.

Distribution of books used to be problematic for many self-publishers, but in the age of the internet this is no longer such a drawback. Direct marketing through an artist’s own website is as feasible as announcing publications in mailings, blogs, newsgroups and social networks. The Independent Photo Book blog (http://theindependentphotobook.blogspot.com/) has been listing independently published photography books since January 2010. New titles are being added nearly every day, and most readers are surprised both by the number and the quality of books they never heard of, and that we hardly ever find in bookshops – the number of specialised photography bookshops exceeds the print run of many of these publications.

The majority of self-publishers operate in a low budget economy. Raising the funds for a book often demands about as much creativity as making the artwork itself. For most artists coming up with a five-figure amount is a bit of a problem, and this is one reason why many artist’s books are made in two-figure editions featuring unusual materials, techniques and forms. Some artists compensate for the lack of money with meticulous craft – emphasizing the material aspects of the book as an object, whereas artists exploring conceptual issues – for which the transmission of ideas is paramount to the material form – prefer materials and techniques that resembles industrial production. Not long ago this would have included photocopy and laserprint; today the obvious choice is print-on-demand.

Print-on-demand providers produce books digitally in small quantities, starting with a single copy. Although most of these services offer a limited choice of book formats, papers and design templates, and although the price per copy is comparatively high, there is one advantage that makes many artists choose this option: print-on-demand is a feasible and affordable way to get your book out there. The internet is awash with photographers’ complaints about the poor print quality or the insufficient binding of these books, and although many of these complaints are understandable, they miss the crucial point: For artists who are not primarily interested in the book as an object ,and whose work is not primarily concerned with print quality the question is not ‘good print or bad print’ but ‘book or no book’. If the answer is ‘book’ you’ll find a way to work within the given limits. Even the most quirky idea that no publisher would ever consider can be turned into a book now, and it doesn’t really matter whether it is printed in an edition of 10 or 100 copies. It’s true, artists have to make compromises when they decide for print-on-demand books; they have to make compromises when working with a publisher too – and when you think about it, most of us have to make compromises all the time, when we go to a restaurant, when we buy a suit and when we get married.

Again, distribution of these books is difficult, as most of them are not even available in specialised bookshops. Some of the print-on-demand providers offer books in their online bookshops but these are rather useless because books of some artistic merit are buried between un-curated piles of wedding albums, personal travel reports and all kinds of amateurish rubbish – and we must not forget that people making this type of book are the ones the companies’ services were originally designed for. Discovering an interesting book in these shops is about as likely as finding a fifty Euro note in the street. Which is why I, together with some colleagues, founded the Artist’s Books Cooperative. ABC is an informal distribution network created by and for artists who make print-on-demand artists’ books. On our website we make available information about selected books in order to help artists get their print-on-demand books to the people who are interested in them.

At this time hardly anybody would dare to make confident predictions about the future of publishing. Nevertheless, I dare say that more artists will make their own books, that more of them will use print-on-demand services, and that the quality of these services will improve notably in the not too distant future. That’s it as far as the future is concerned; in the meantime, let’s have one more look at the past to disperse another common assumption: self-publishing is an option for aspiring authors who will convert to established publishers as soon as they are acknowledged. Whilst this may be true for some artists, there are a couple of fine examples proving the opposite. After years of working with and for various publishers, Claire Bretécher started publishing her comic books herself, and never returned to the world she left behind. Her compatriots, Goscinny and Uderzo, published their Asterix series themselves from the very beginning. In Japan, the vast majority of comic books have been self-published for decades. And it’s not just comics, we find the same attitude in serious science, too. Maria Reiche had researched the Nazca lines in Peru for ages. She decided to publish The Mystery of the Desert – which turned out to be a major success – herself. Asked why she chose this way of working, she came up with one simple and convincing reason: ‘No publisher is going to drink champagne from my skull’.

[/ms-protect-content]

Published i Photoworks issue 14, 2010

Commissioned by Photoworks