From issue: #25 Multiplication

Clément Chéroux, 06 December 2024

Stories of people who have little; of people who are invisible, or hidden; portraits of the unknown, of the nameless, the downtrodden; chronicles of ordinary, humble, or forgotten lives—for a few decades now, a whole section of the historical discipline has attempted to retrace the history of those who, unlike crowned leaders, elites, celebrities, et cetera, have left few or no traces. Researchers in the United States call this “history from below.” A few years ago, I attended a historians’ conference centered on this question. The organizers tried to provide a genuinely universal program; almost all of the main currents of contemporary thinking were represented. A follower of the French philosopher Michel Foucault wanted to continue exploring police archives in order to bring together the lives of “infamous men,” the insane, murderers, or monsters of abomination—men who, in Foucault’s words, allow us to hear that “language that comes from elsewhere or from below.”[i] A Marxist historian paid homage to the memory of Jean Maitron and pleaded for the continuation of his great work, the Dictionnaire biographique du Mouvement ouvrier français (Biographical Dictionary of the French Workers’ Movement), published between 1964 and 1997 in forty-four volumes (and a CD-ROM), which, beyond the guardian figures of the left, collates the lives of thousands of militants. One participant retraced the history of the first media campaign of the Movement de libération des femmes (Women’s Liberation Movement), which, on the initiative of Monique Wittig and a few others on August 26, 1970, left a bouquet of flowers under the Arc de Triomphe in Paris in tribute to the wife of the Unknown Soldier. A number of academics from across the Atlantic analyzed the dynamics of an American society in which the protest movements of the 1960s have elevated the roles of minorities, including Indigenous, Black, Hispanic, Asian, gay, and trans people. A historian of photography focused his paper on one of the most frequently mentioned operators of the nineteenth century, a certain A. Nonymous, about whom nobody knows anything—except that this person sometimes used the pseudonym U. N. Known.

[i] Michel Foucault, “Lives of Infamous Men,” trans. Robert Hurley and others, in Power: Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984 (London: Penguin, 2002), 3:161.

At the dinner that followed the conference, between two courses and after a few glasses of wine, I had the idea—a rather crazy one that I readily shared with those next to me—that, among all of those that capital-H History has neglected, we should perhaps not forget the twins who remained hidden behind famous brothers or sisters. I was thinking of Iron Mask, that mysterious, hapless character who spent almost his entire existence in captivity, his face hidden, because, according to Voltaire, he was the twin brother of Louis XIV. Or Ashraf Pahlavi, twin sister of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran. Closer to us in time are the twin sister of Isabella Rossellini, the twin brother of Vin Diesel, and the twin brother of Scarlett Johansson, to name but a few. A psychology degree is hardly required to understand the challenges of living in the shadow of someone who has the same genes, but is constantly in the spotlight. And this, to my mind, only makes these anonymous twins more worthy of appearing in a history of the forgotten of history. This strange idea, which jumped out of my mouth like a jack-in-the-box, puzzled my dinner companions a little, but did not come from nowhere. At the Société française de photographie, where I worked at the time, I had, a few weeks before, received a visit from a British historian whose research consisted of showing that William Henry Fox Talbot had had a twin brother. This genetic-historical detail explained, for him, why, unlike Nicéphore Niépce, Louis Daguerre, or Hippolyte Bayard, whose photographic processes offered directly positive but unique images, Talbot had invented the principle of the negative—the matrix from which it is possible to create several almost identical copies.

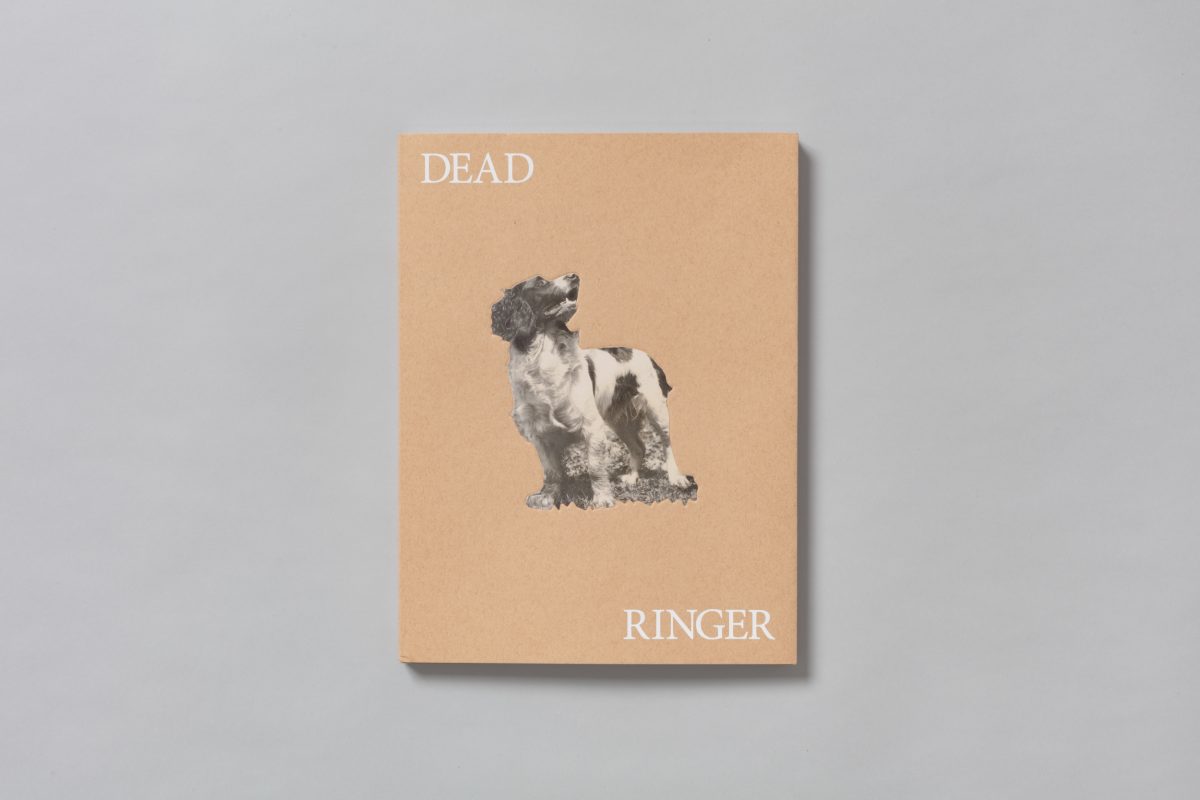

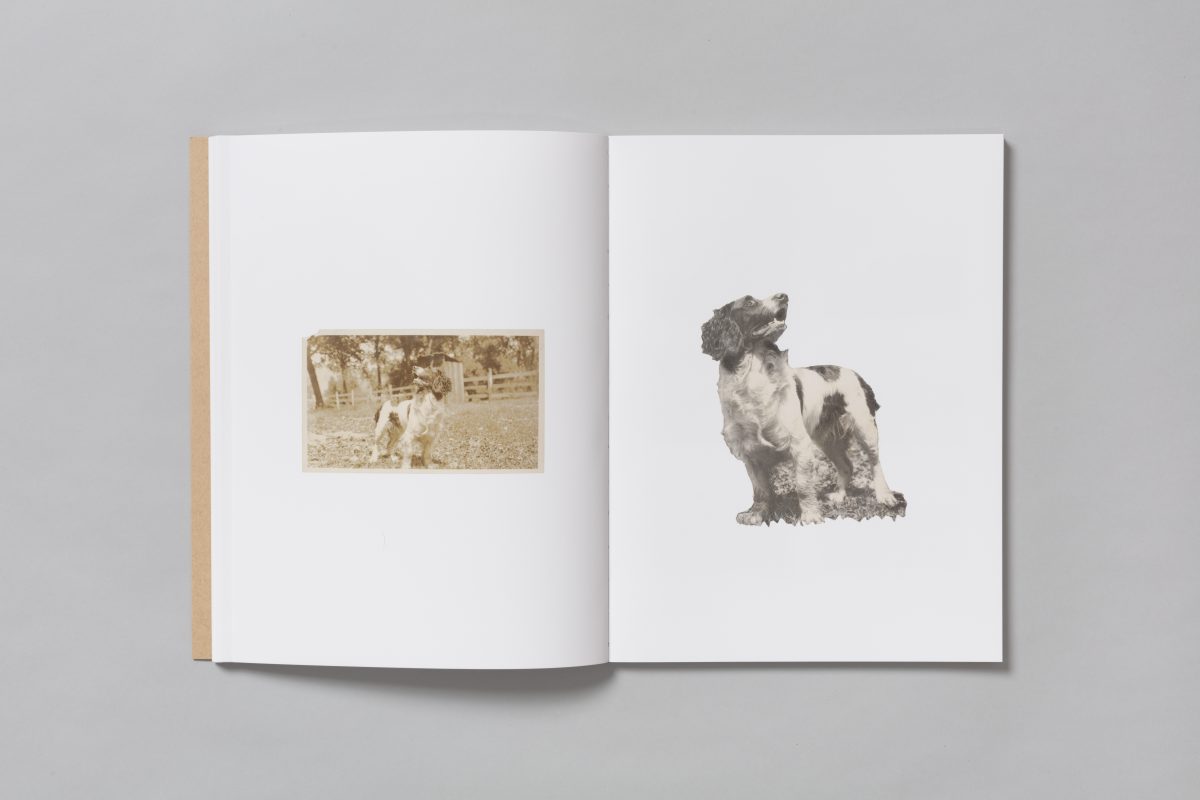

I had listened to my interlocutor politely, but the absence of probing archival documents, paired with his convoluted arguments and repeated use of a hesitant conditional tense—Talbot’s twin would have died at birth—left me in doubt. A quick internet search today confirms to my mind that his hypothesis was more a historical invention than a path of serious research. Yet the premise was appealing, given how photography, in its British form at least, seems to have been born under the sign of Gemini. The different theoretical currents that have taken hold of the medium, from realism to index theory, strongly emphasize its ability to reproduce identically. “Photography belongs to the world of the double,” states Chris Marker in his 1966 film Si j’avais quatre dromadaires (If I Had Four Dromedaries).[i] In the shooting, and then the printing, photography is in fact doubly double. First of all, it has the capacity to duplicate what is in front of the lens in order to offer a relatively faithful copy. It offers then the possibility to multiply the prints, which will be identical and supposedly infinite. It is this second form of duplication that is discussed in the book you are holding by Yael Eban and Matthew Gamber, entitled Dead Ringer, an expression from the horse-racing world meaning “exact copy.” Ever since Pictorialism reigned at the turn of the twentieth century, and perhaps even more since the art market took hold of the medium of photography in the 1980s, everything seems to have been orchestrated to make us believe in photography’s unicity. But this has obviously never been quite true. Photographic works are, in most cases, published in editions, in several copies, and sometimes in different sizes in order to increase their number. Practical photographs—in medicine, in police procedure, in insurance—are also mostly multiple. Amateur photographs, which we once might have regarded as entirely unique, also often exist in numerous copies. The photograph is therefore more generally multiple, in line with what Talbot imagined.

[i] Chris Marker, “Si j’avais quatre dromadaires” (1966), in Commentaires 2 (Paris: Seuil, 1967), 88.

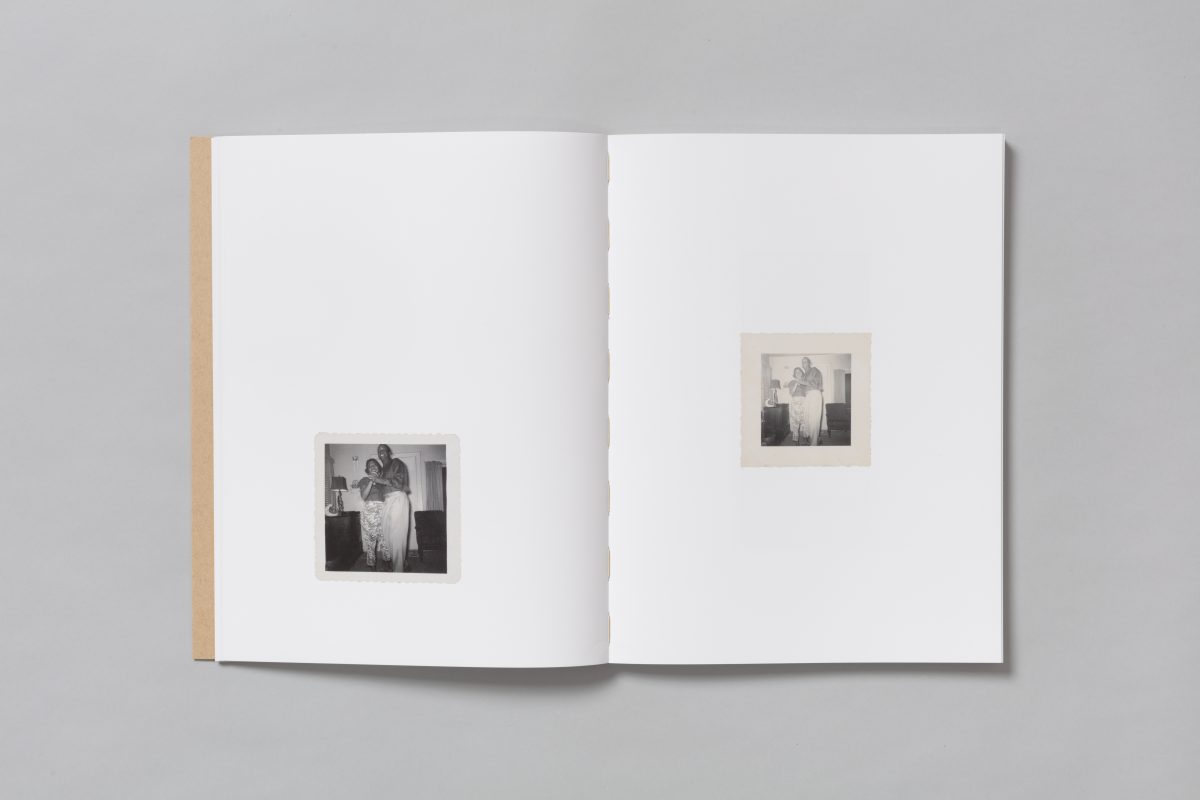

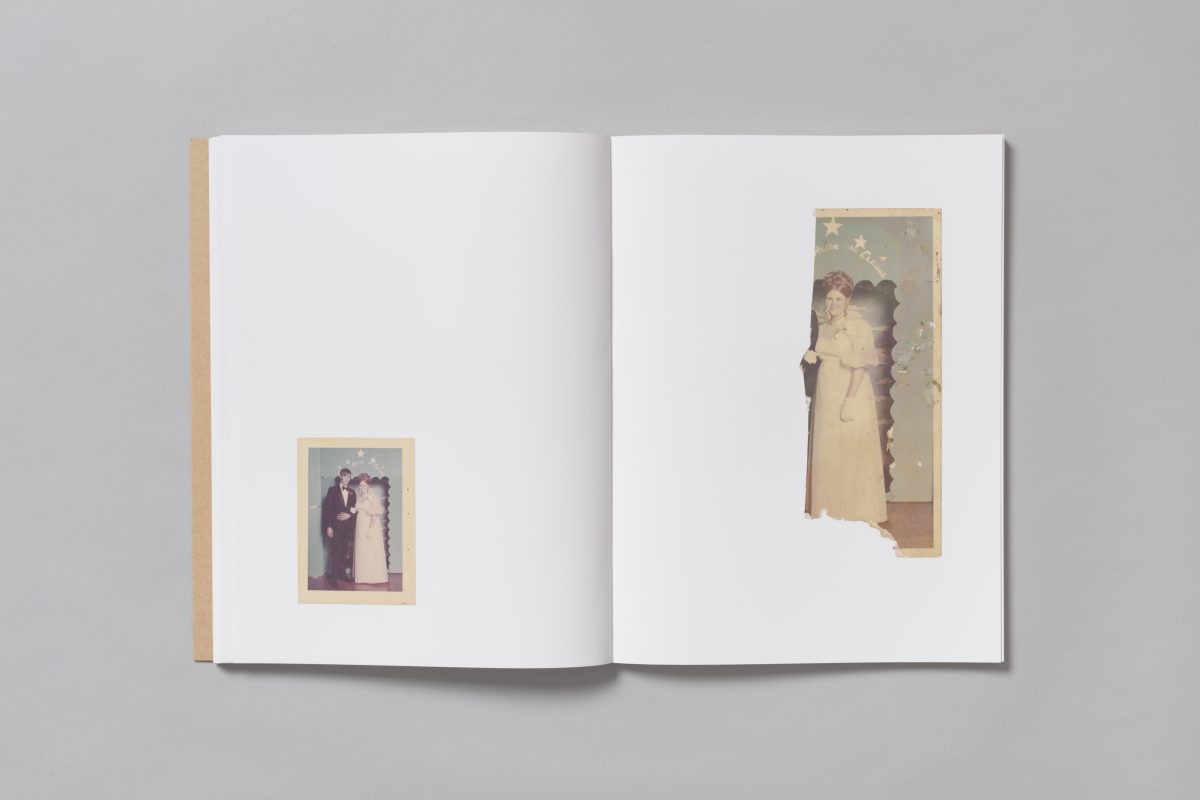

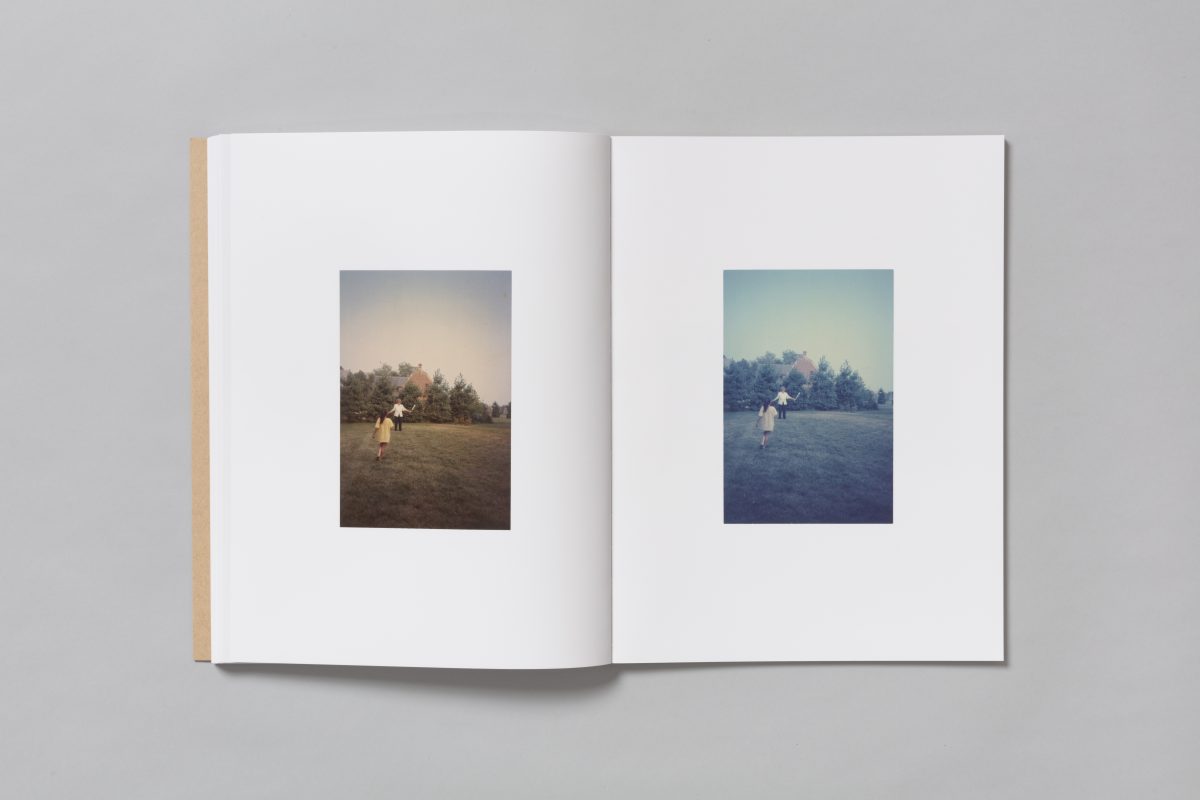

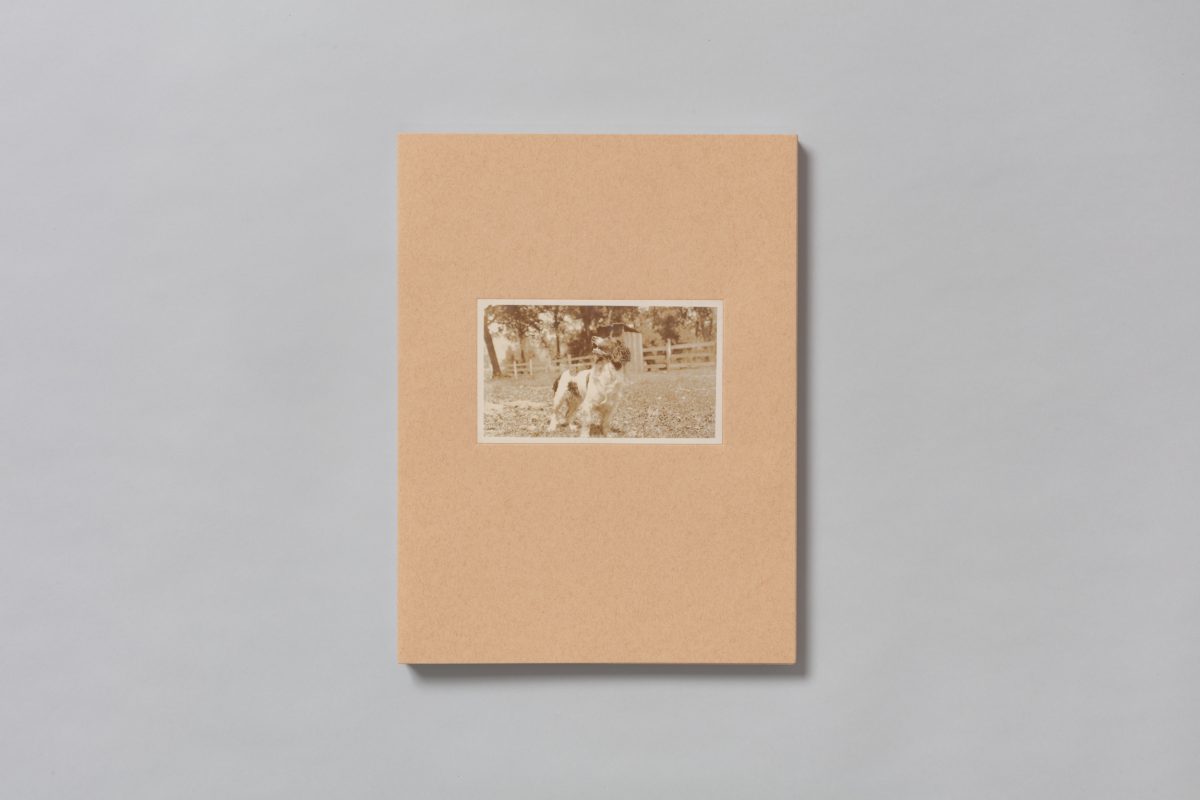

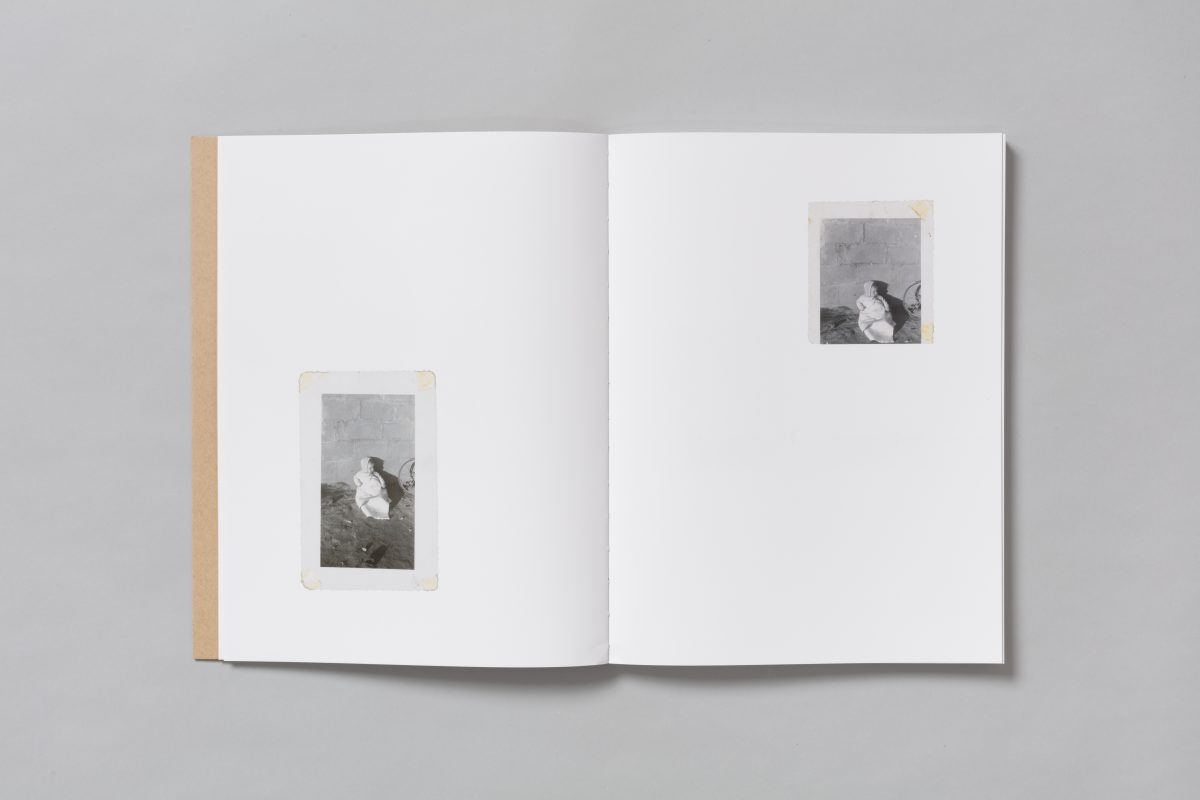

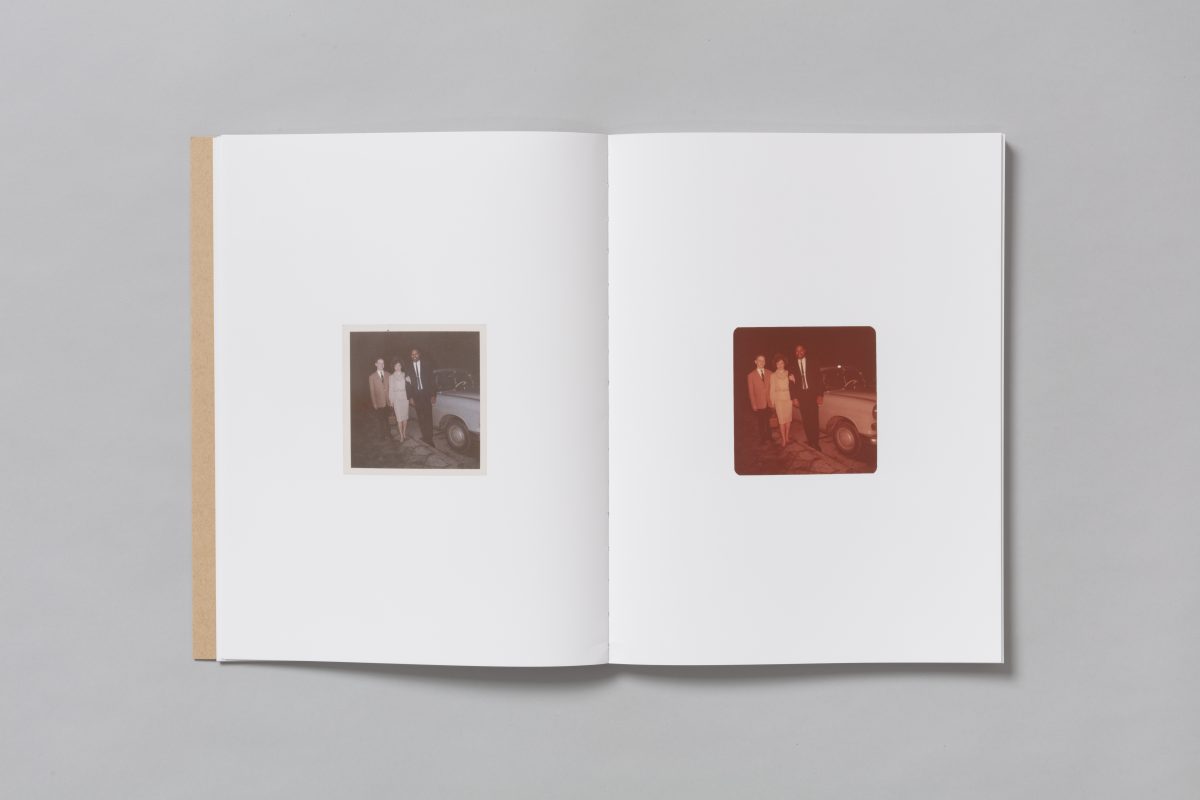

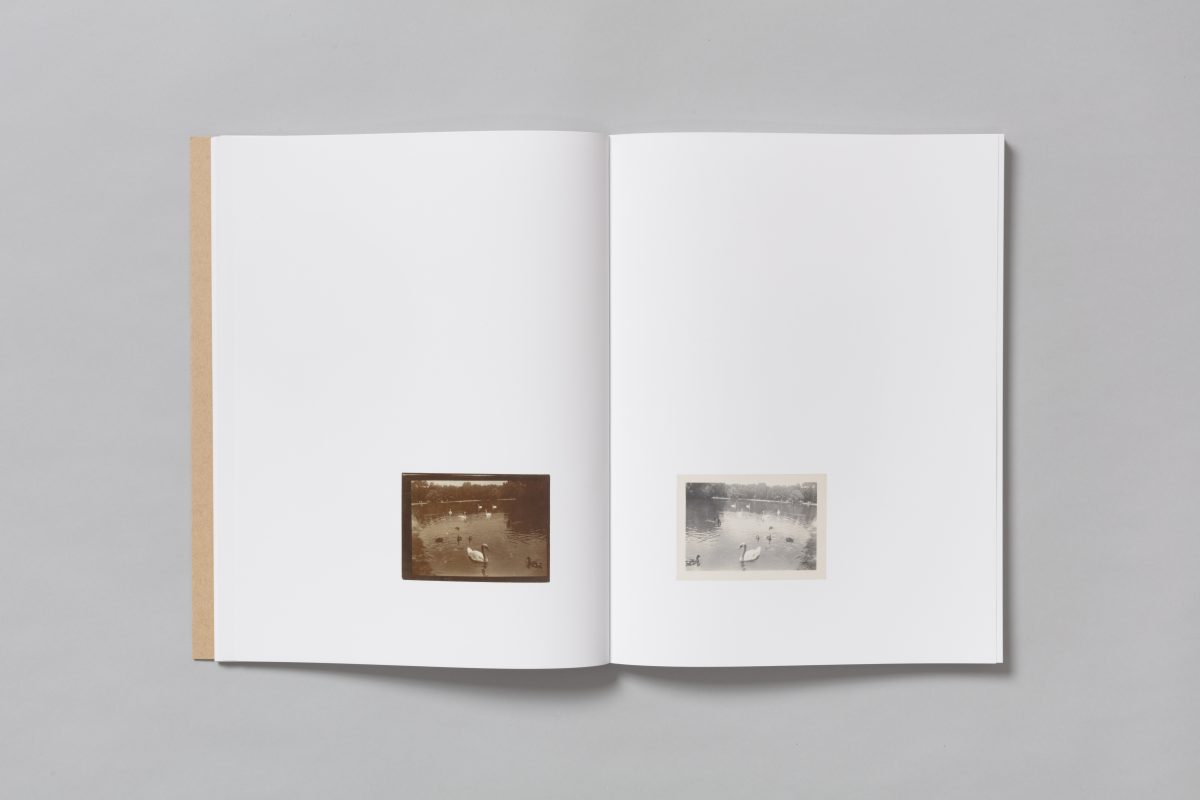

The present volume exemplifies perfectly the reproducibility of photography. It is entirely composed of amateur photographs collected by Eban and Gamber in flea markets or bought online. Both of these artists have worked in photographic archives: Eban for the New York–based collector of vernacular photographs Peter J. Cohen, and Gamber on digitization projects for Harvard University and the Boston Public Library. Given that Hannah Höch and Richard Prince also both worked in photographic archives (Ullstein Verlag and Time-Life, respectively), we can glean the impact of this kind of professional experience on an artist’s creativity. In recent years, many collections of amateur photographs brought together by artists from different backgrounds have been presented as artworks in their own right. I am thinking of Christian Boltanski, Joachim Schmid, Tacita Dean, Céline Duval, Jason Lazarus, and Melissa Catanese, to mention but a few. But unlike these examples, the images collected by Eban and Gamber always go in twos. Each pair comes from the same negative. As they explain, their project is “an exploration of duplication in vernacular photography.”[i] In the 1970s and 1980s, a number of large photo developing chains advertised, for a nominal extra charge, a bonus photo. For instance Snap-Pak Photo Service offered to make duplicate prints from the developed negatives: one “for the album” and the other “for the wallet.” In the majority of cases, the images today look just the same. But sometimes, after being printed, they had different fates. When one remained in its envelope and the other was, say, tacked to the wall, they aged differently. One might have been reframed, touched up, or cut up (perhaps to remove a person no longer in favor). Or stained, worn, or torn. One image might have been printed backward or with paler colors.

I would like to be able to film my pupil while it examines each spread of this book. I imagine that my eye oscillates from one photo to another. It hesitates and panics, scanning rapidly the gap between the two. It is taken aback by the image that stutters, hiccups, and repeats itself. Facing these duplicates, I feel like Yakov Petrovich Golyadkin, the hero of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel The Double (1846), who never stops referring to “this and that.” In truth, there are different ways to envisage these image-couples. The first involves considering them essentially through the prism of dissemblance. Since no single thing in this world can be absolutely identical to another, according to Heraclitus’s famous phrase, these photographs are necessarily all distinct. And the most seemingly perfect reproduction will always be missing the here and the now of the original, as Walter Benjamin famously put it. As in the popular children’s “spot-the-difference” game, I begin comparing, back and forth, seeking the differences. The essence of this exercise most of the time involves hierarchizing. For example, of these two prints, which one is the original, and which is the newer? Or simply the better? Another approach involves accepting the fact that the elements of each pair resemble one another. Bis repetita placent—the doubling pleases—says the Latin phrase. Allowing my gaze to wander from one to the other, I fall into a sort of ecstatic contemplation. A few years ago, the French essayist Marc Le Bot made the interesting suggestion that our fascination with the double is linked fundamentally to the symmetry of our own bodies: two eyes, two hands, two lungs, and so on.[ii] Facing these doubles, the homo duplex—as he explains using words from Émile Durkheim’s sociology—finds something of the symmetry that constitutes oneself. There is certainly something quite satisfying in the squaring of the mirror effect. It has come full circle: Narcissus is reassured by his own reflected image. A third way to apprehend these twin images is to acknowledge that they can be both similar and dissimilar at the same time. Even as I shift my gaze back and forth, I might ascertain neither their identicality nor their difference.

[i] Yael Eban and Matthew Gamber, “Dead Ringer,” two-page presentation note sent to the author, 2021, p. 1.

[ii] Marc Le Bot, “Le corps double,” in Le Deux, revue d’esthétique (Paris: Union générale d’édition, 1980), 28.

In front of these double images, I feel like I am facing twins—and here I have returned to my earlier point. I remember witnessing, a few years ago, a particularly instructive scene on the metro in Paris. A ten-year-old boy was sitting with his mother in front of identical twin boys. My seat was almost opposite and I observed the situation with much curiosity. Not only did the twins resemble each other, but they were also dressed exactly the same, to the smallest detail. I watched the child’s little head of curly hair as it nodded from one to the other. I saw as well a certain embarrassment appearing on the faces of the two brothers. The writer Irving Stettner, twin brother of photographer Louis Stettner, described in one of his short stories the unease he felt when, in a public space, someone’s gaze focused too much on them: “Being born an identical twin. . . . Always the feeling of being an anomaly, what. Nature had played a practical joke, and I was simply part of it. To go through life with my alter ego or double right at my side, that was my fate. Still as we were truly identical, Harry and me, both with the same exact nose, eyes, hair, so on, whenever we walked down a street together we were sure to get plenty of attention, a host of silly-ass grins. Willy-nilly, we’d leave behind us a blazing trail of merry smiling faces. All of which inclined to keep us in a light gay mood. Yes, it was amusing—but also confusing, as friends, neighbors, teachers, etc. would frequently mistake one of us for the other. Then public school began; as long as we were in the same class, things went smoothly. But soon as one of us sat in a different classroom, the cases of mistaken identity became epidemic. Walking a school corridor I’d be approached endlessly by strange faces, but with a warm, friendly glint in their eyes, ‘Hi Harry!’ Times I began to doubt that I was a distinct human entity.”[i] This is probably what the twins felt in the Paris metro. The staring child finally turned to his mother to ask—in an innocent voice that betrayed a certain anxiety—“Are they the same, or not?”

Seldom do we find ourselves confronting something while experiencing its opposite at the same time. An object, when touched, is rarely both cold and hot simultaneously. One given moment cannot belong both to the past and to the future. Yet identical twins are both identical and different. This is what French psychologist René Zazzo called the twin paradox. Even when they are born and educated in the same family environment, twins are likely to develop quite dissimilar personalities. Conversely, twins separated at birth and brought up in very different social environments can nevertheless have very similar destinies.[ii] This apparent contradiction undoubtedly explains the extraordinary attraction that twins have exerted in the collective imagination since the Bible (Jacob and Esau) and Greek mythology (Romulus and Remus) as well as Roman (Castor and Pollux), Norse (Freyr and Freyja), and Aztec mythology (Xochipilli and Xochiquetzal). Obvious examples from more contemporary popular culture include Lewis Carroll (Tweedledum and Tweedledee), Mark Twain (Luigi and Angelo Capello), and David Cronenberg (Beverly and Elliot Mantle of Dead Ringers). A lot more could be said about the cult of twins in Yoruba communities, or about Cathleen and Colleen Wade, the two identical sisters photographed by Diane Arbus in 1967 whose haunting presence was the inspiration for a famous scene in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining before it became a motif in countless advertising campaigns. André Breton had no twin brother or sister, but he too was fascinated by these antinomic situations. In 1930, in the Second Manifesto, he wrote: “Everything tends to make us believe that there exists a certain point of the mind at which life and death, the real and the imagined, past and future, the communicable and the incommunicable, high and low, cease to be perceived as contradictions. Now, search as one may one will never find any other motivating force in the activities of the Surrealists than the hope of finding and fixing this point.”[iii] The associations of images comprising this collection are on the same level as this “supreme point.” They are part of this form of exploration that, from the Kabbalah to dialectical theory to the movement championed by Breton, likes nothing more than to subsume paradoxical situations in an epiphanic synthesis.

[i] Irving Stettner, “Trouble with Twins,” in Thumbing Down to the Riviera (New York: Lionsong, 1986), 52. Stettner has changed the names, but there is no doubt that he is writing from personal experience.

[ii] René Zazzo, Le Paradoxe des jumeaux (Paris: Stock, 1984).

[iii] André Breton, “Second Manifesto of Surrealism” (1930), trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane, in Manifestoes of Surrealism (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972), 123–24.

Notes

Translated from the French by Shane Lillis

Clément Chéroux is the director of the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation in Paris. Prior to that, he held positions at MoMA (Chief Curator 2020-22), SFMOMA (Senior Curator 2017-2020), and Centre Pompidou (Curator and Chief Curator 2007-2016). Chéroux is a photo-historian. He holds a PhD in Art History. He has curated numerous exhibitions and published more than 50 books about photography and its history.

Yael Eban and Matthew Gamber’s collaborative and multidisciplinary practice investigates the role of photography in material culture, specifically focusing on mass reproduction. Both artists have worked in photography archives, which greatly informs their artistic endeavors.