Angelina Ruiz, 02 May 2025

The archive is multipurpose, constantly shifting, taking many forms and existing whether or not we are around to see it. In a familial archive, it’s personal–bringing joy and prompting memories of the past, reminding us of our histories and the legacy of our ancestors. But a public archive, a historical one, is something less curated, and rather a reflection of our history as humans, showing us both the good and bad, and what the human race is capable of. The ongoing and increasing surveillance worldwide has created a perpetual record of our existence, unbeknownst to many.

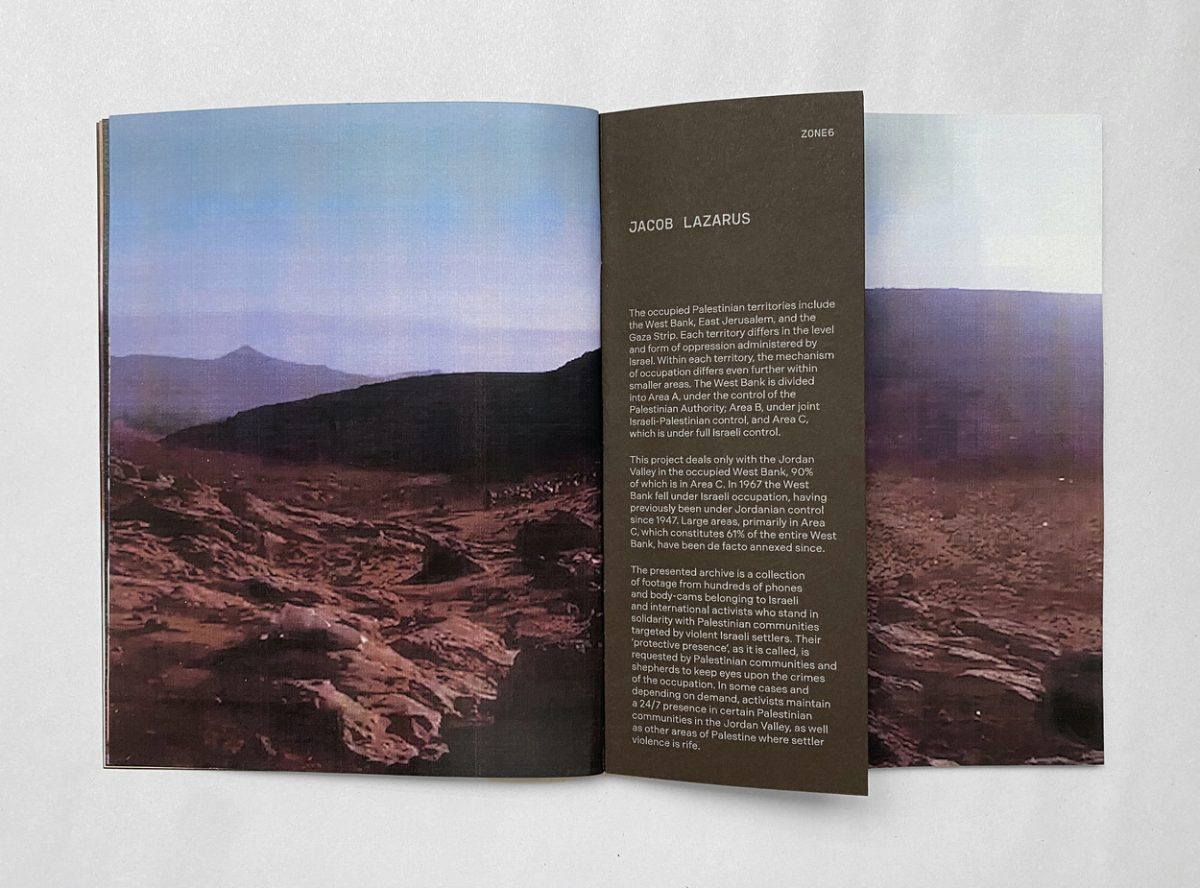

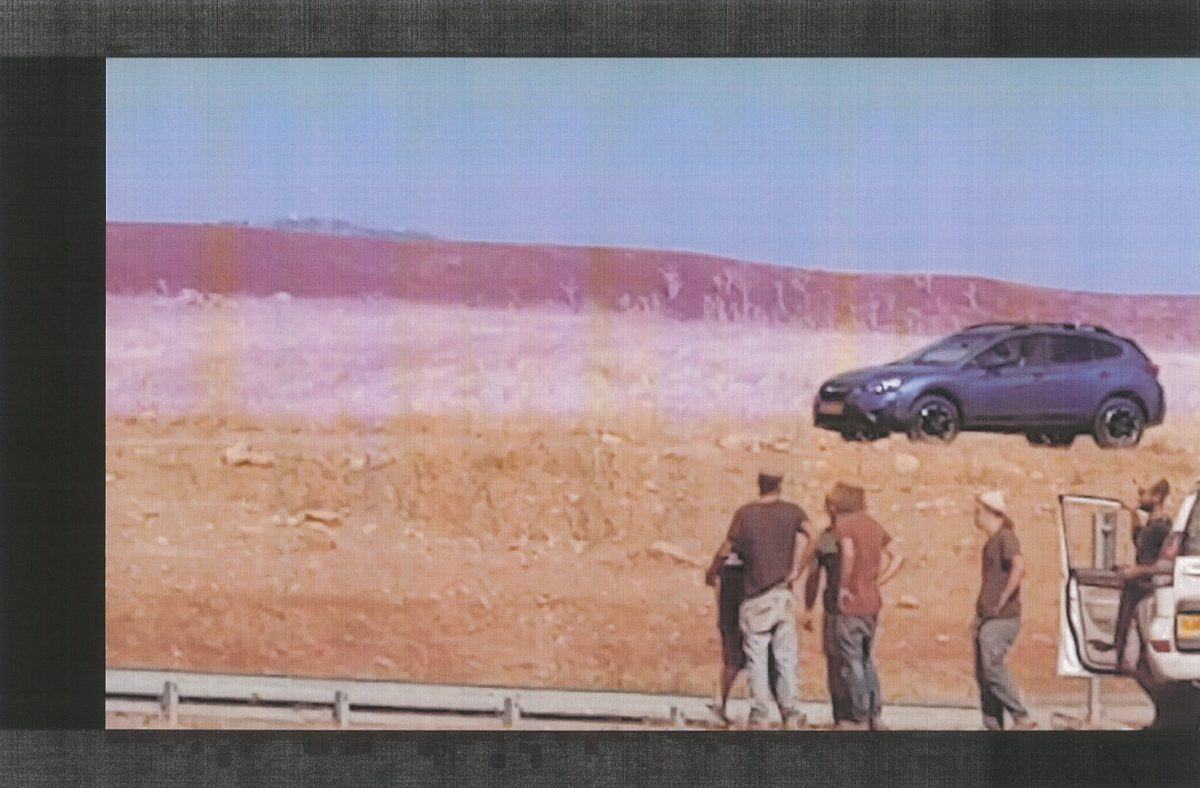

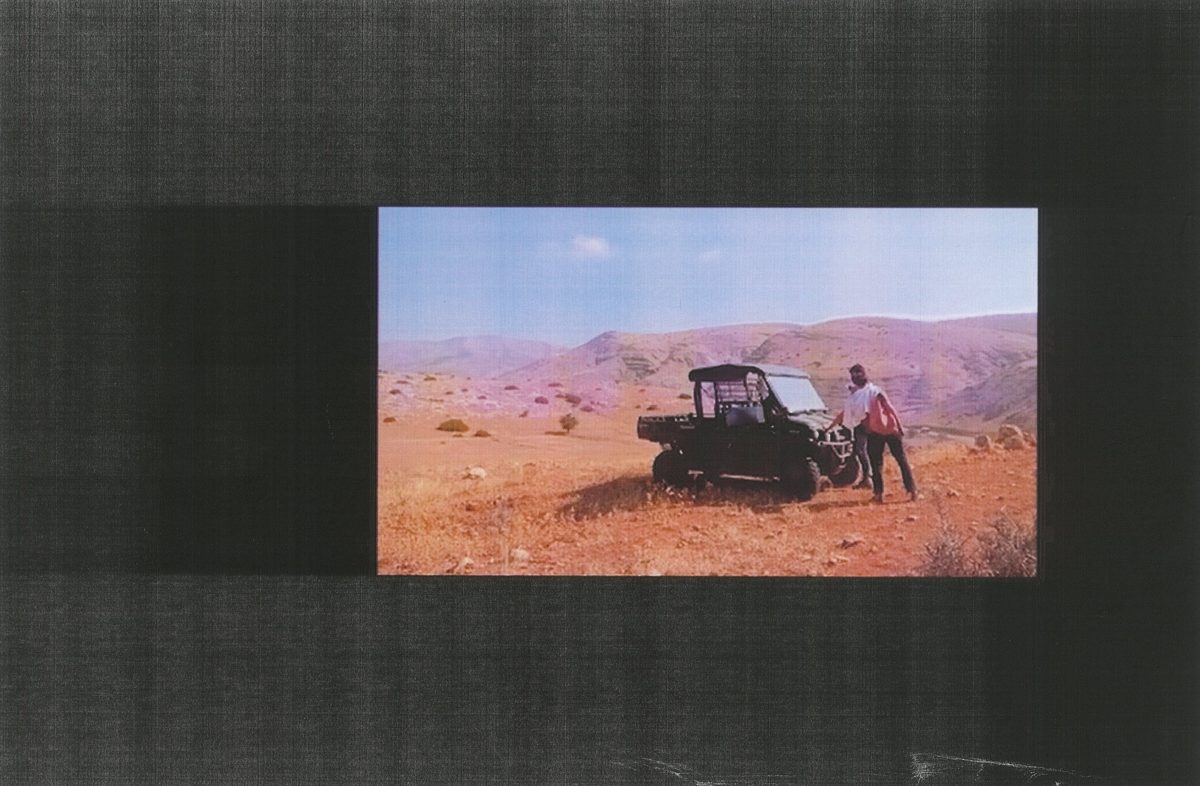

In Frames of Annexation (2014) by photographer Jacob Lazarus, video footage from phones, body-cams, dash cams and CCTV are compiled, documenting years of the Israeli occupation, alongside human rights abuses and activism in West Bank, Palestine. Lazarus, originally from London, found himself at the crossroads of both journalism and art. After moving to Jerusalem to continue his work in human rights, he was stuck trying to figure out how to tell the story of an ongoing occupation that did not involve his own imagery. This led Lazarus towards his work with the Jordan Valley Activists, a group of Israeli activists that exist as a buffer to both prevent and de-escalate any acts of violence, as well as document crimes that are being committed against Palestinians.

In the book iteration of the project, he writes that this media from the archive is used “as evidence in the Israeli military courts to defend Palestinians, in the international arena to lobby against violent settlers, and in the public forum of social media, holding these crimes in our collective conscience.” He continues, referring to this archive as both “violent, slow and enduring.” But he also holds the dialectic that much of this footage often triggers people online and can become reactionary. Lazarus feels frustrated with the way imagery is commonly encountered on social media. He says, “I wanted to think about, how can an audience engage in a more prolonged way than just seeing this footage, scrolling, and forgetting?” So, he pivoted to using the activists’ existing archive, one that had been made with the intention of both protection and as a safety presence. Lazarus refers to the act itself of filming as preventative–it’s their existence that serves as an interruption of the violence.

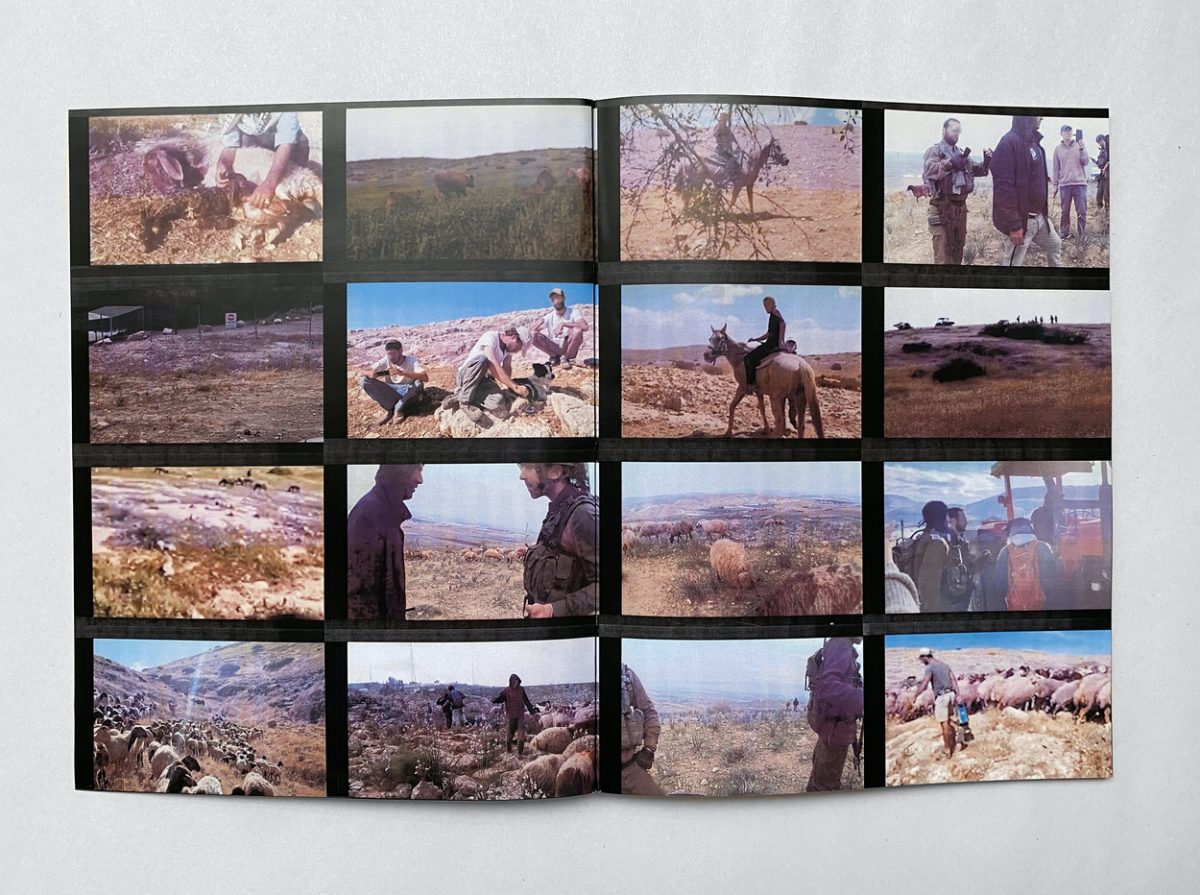

Understanding the weight that these images held, the footage was presented in May 2024 in Peckham, London, as an interactive video/print installation that allowed people to select stills from each of the videos. For Lazarus, the goal was to make people active participants of this project. With the video archive playing on the screen and a printer below it, they were instructed to click a button and choose a frame to print. By taking this media out of its original context (for documentation purposes), it forced people to engage and witness these atrocities. Lazarus goes on to explain that the installation allowed for one to sit with the imagery for a bit longer and digest what was happening on the screen. With the archive spanning eight years, there are countless stills, from farmers on their land, to landscape photos, and up-close images of people engaging with whomever was behind the camera. We are left to wonder, were they met with peace, or hostility?

The panoptic gaze in this archive is rampant, but Lazarus offers us a small solution in Frames of Annexation (2014), by blurring the faces of those in each image. This choice helps protect the identity of those in each image, refusing to feed into the surveillance state which these images traditionally exist in. Still, he said he struggled with the lack of consent, as well as the decision to continue with a project in a moment where the violence is so prevalent. “Since this zine [has been] published, three of the seven communities that were depicted in the footage [were] ethnically cleansed.” Lazarus continues, “It’s not like it’s some historical artifact that an archive would normally talk about. The way we talk about an archive as something which is happening in the past—it’s really just something that’s happening…” When looking at an archive of this subject and magnitude, the question of ownership persists. Who is the real author of these images, or rather, who gets to decide what is done with them? One can argue that this media is already public and being gathered as documentation, but it still wrestles with the ethical dilemma of documenting people as just bodies. Truthfully, when living in a surveillance state, one unwillingly sacrifices their bodily autonomy, turning their human form into a record.

The sequencing in this project was also significant to the narrative, as Lazarus notes that each print in the book was not placed in a specific order but rather placed in the sequence in which they came out of the printer. The book reads, “The resulting publication is democratic, dialogic, and collaborative. It should exist as an artefact that advocates—an educational tool that both informs and enrages, emboldening us to act. We hope that this book urges collective resistance to the passive consumption of imagery that regularly dominates our lives.”

Frames of Annexation (2014) is just as much art as it is evidence. Lazarus isn’t actively trying to tell a side of a story, but instead, presents footage of events that genuinely happened. Nonetheless, he wanted to present it in a nontraditional way, hoping that it would inform people. “If you’re confused, look it up,” he says. “Go do the legwork, which I feel like people can be lazy about and they want to be fed all the information, and ‘tell me why this is wrong,’ or ‘tell me why this is right?’ I’m not gonna do that for you.” Fortunately, artists like Lazarus still exist, using their craft to pave a way for stories that are systemically suppressed. Solidarity comes in many forms, but tapping into humanity brings something different to the table—it refutes violence with compassion.

Angelina Ruiz is a Queer Puerto Rican artist and writer, based in Hudson Valley, NY. Their work surrounds arts and culture at the intersection of gender, sexuality, and race.

Jacob Lazarus is a British documentary photographer and filmmaker based in Israel/Palestine. He is a recent graduate of Documentary Photography from the University of the Arts, London.