By Róza Tekla Szilágy, 12 December 2025

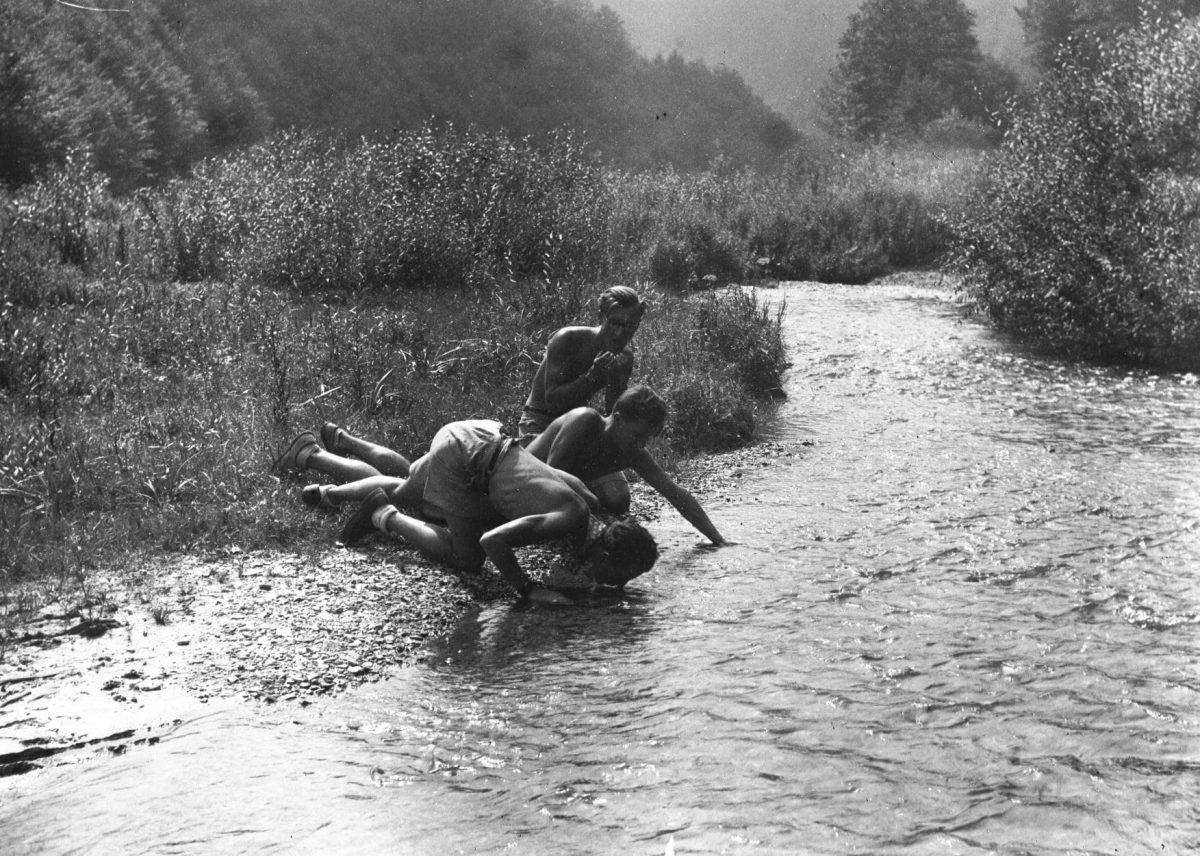

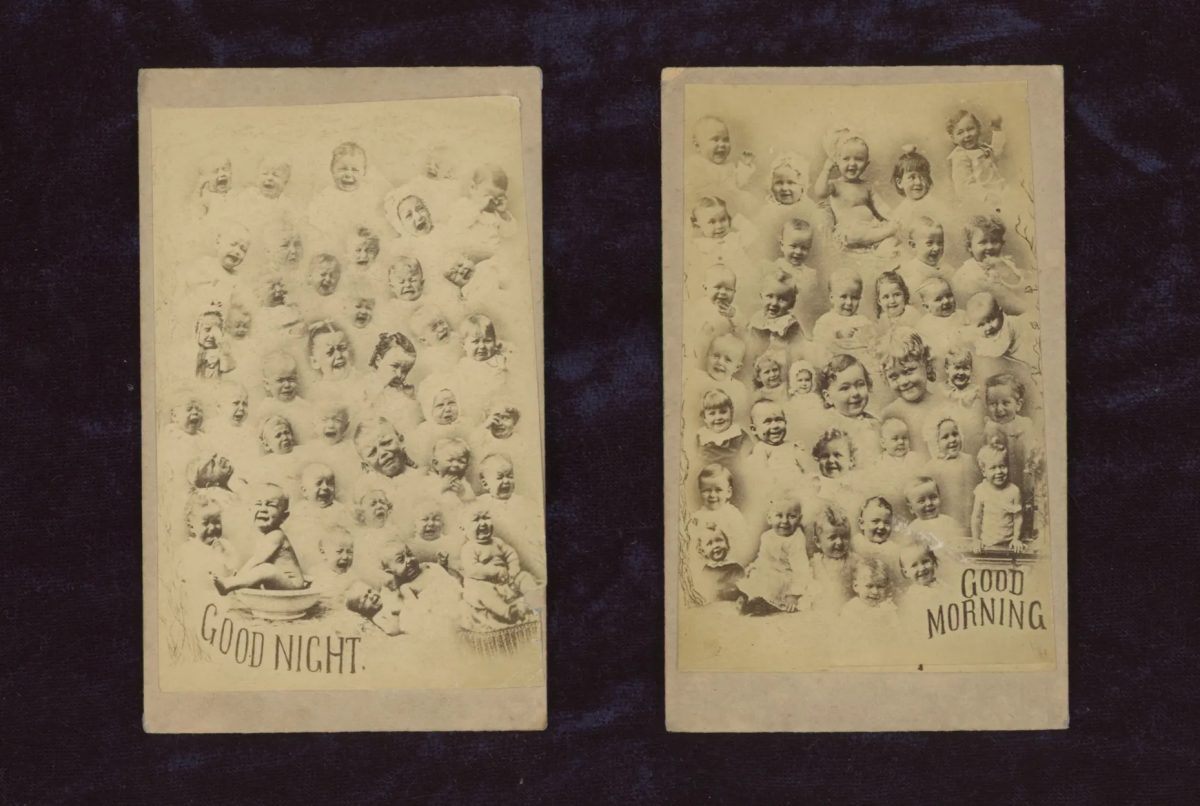

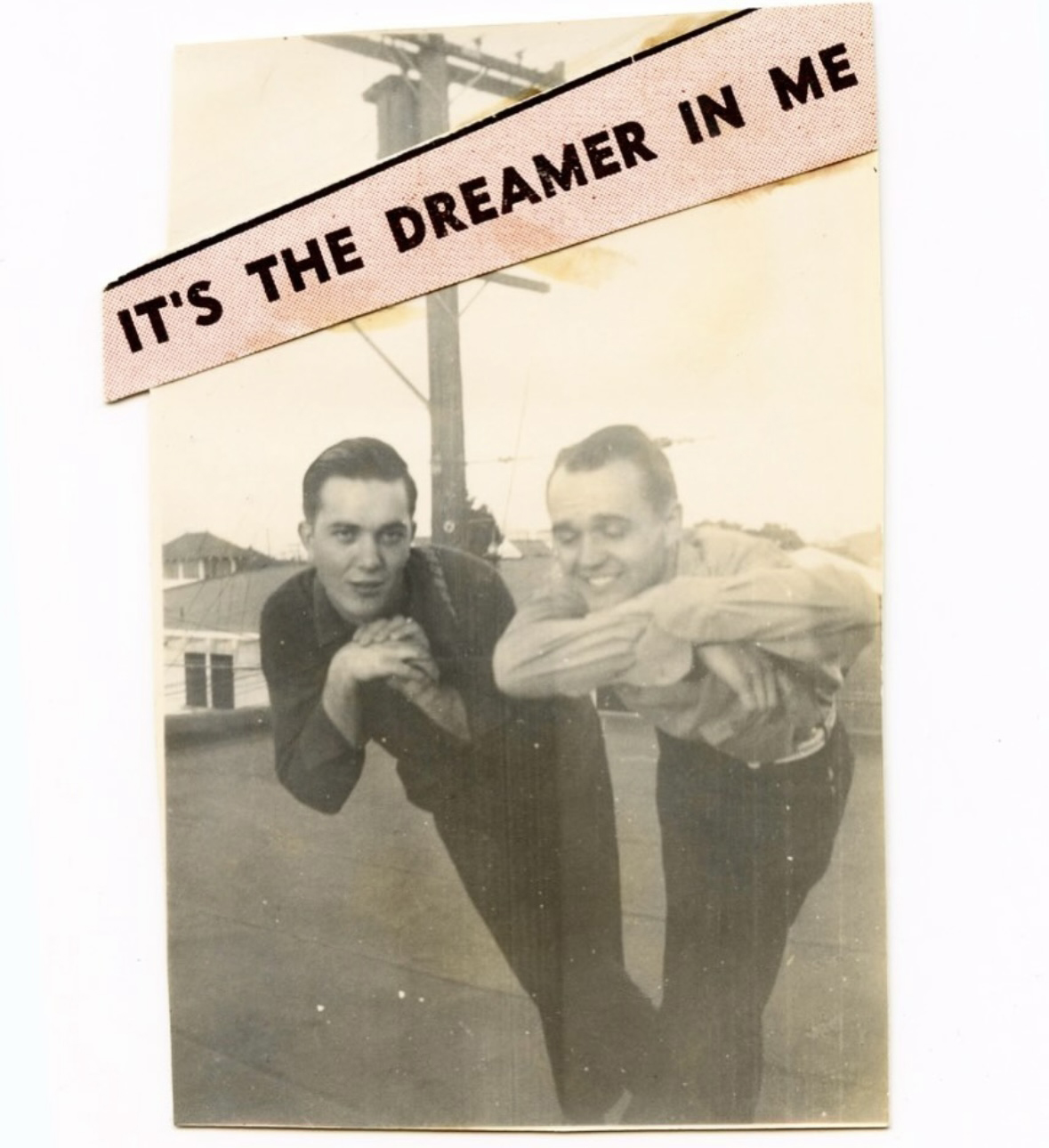

I would like to propose an idea: the often-overlooked everyday photography collectors are the unsung heroes of photography history. When I use the phrase’ everyday,’ I think about the vernacular, the found, the banal, the ordinary, and the domestic photographs – the family albums, archival materials, and amateur snapshots.

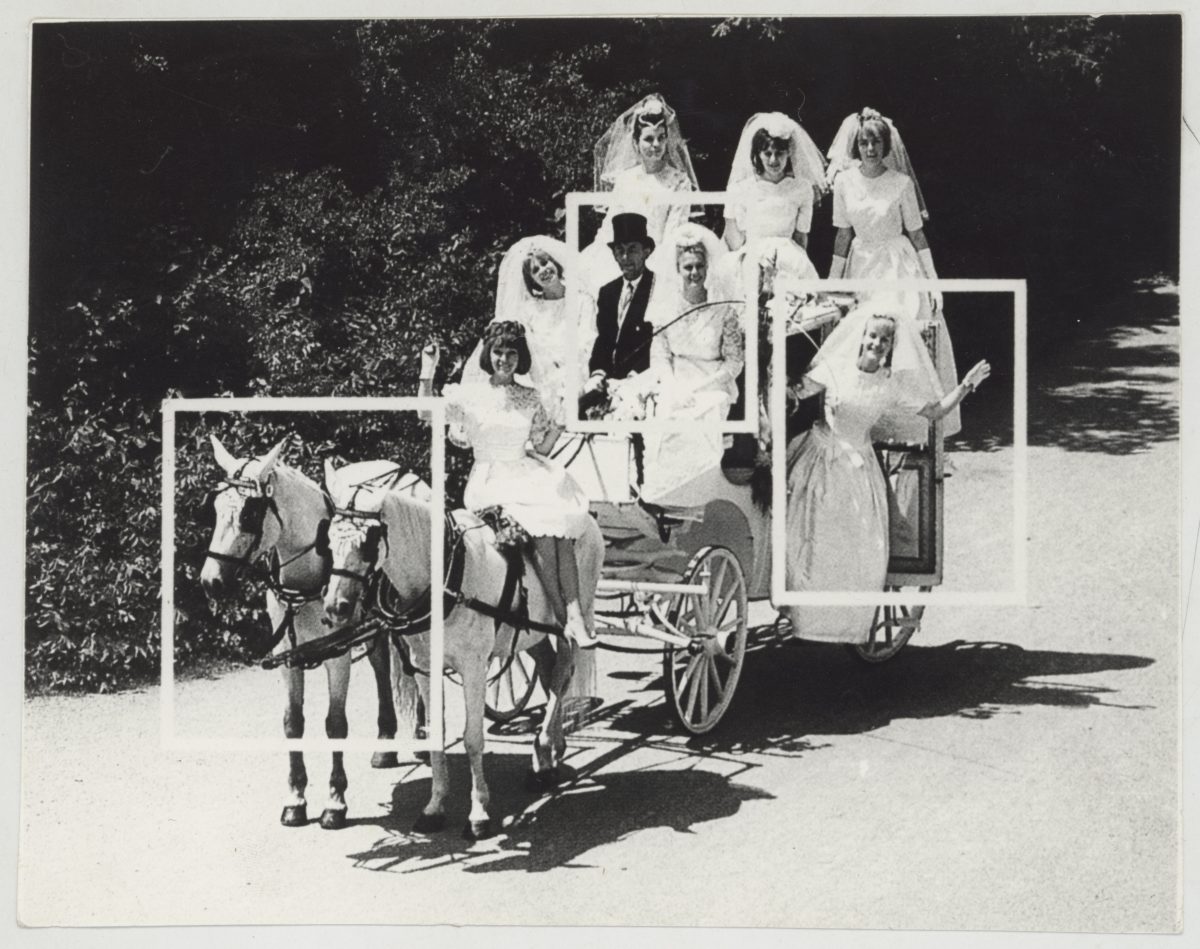

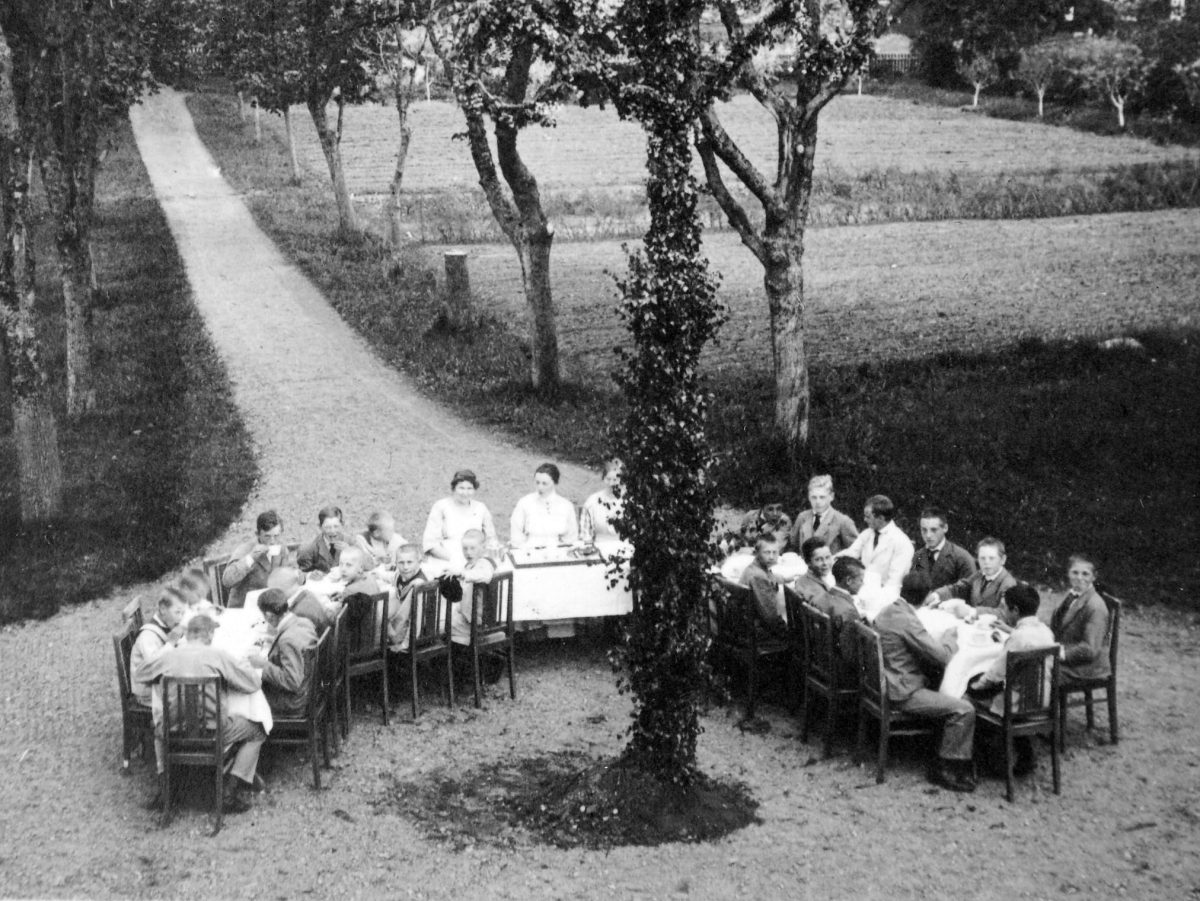

Everyday photographic creation is something we all participate in; the luckier among us have family albums that span several generations, and we all know or utilise various ways of looking at these photographs, even discussing them during family gatherings. Though family photographs and albums are the core unit of past times’ everyday photography, there is much more to the avid amateur photographers – all the photographic modes that have inscribed aspects of domestic life, whether governmental, conflict-oriented, celebratory, or oppressive.

But how are we able to access all this material – how can those of us who would love to indulge in analysing it, taking a contemplative look at it, actually find material to look at, to curate, to celebrate, and to develop best practices for working with it ethically? One thing is the personal attachment: the artistic projects span from the self-reflective overview of one’s own past and family heritage. Still, this image material is far vaster, and the whole landscape is so much bigger. How can we hope to build an understanding of our shared past and present if these photographs are not safeguarded and made accessible – in multiple forms and through multiple channels – to a broader public?

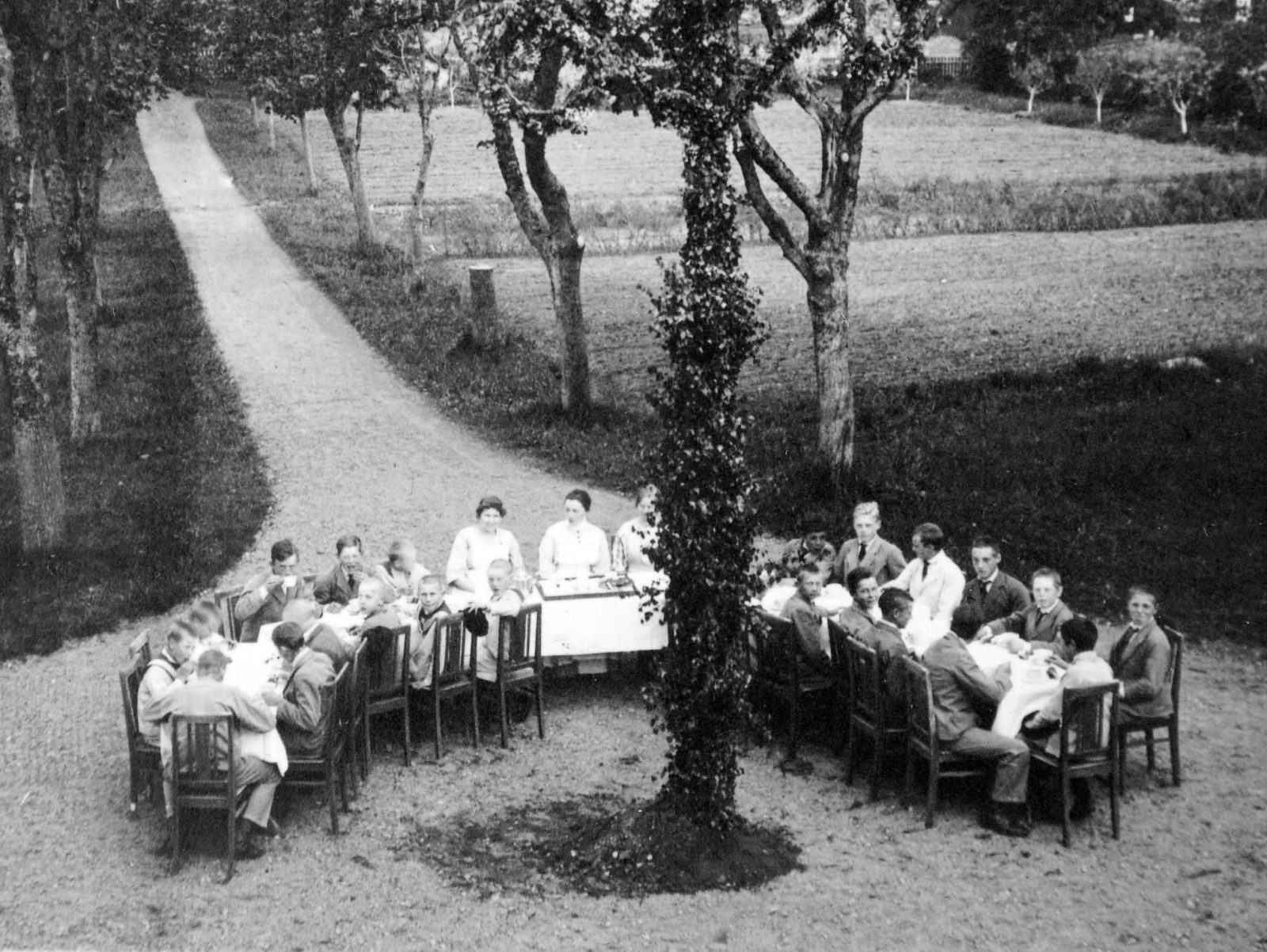

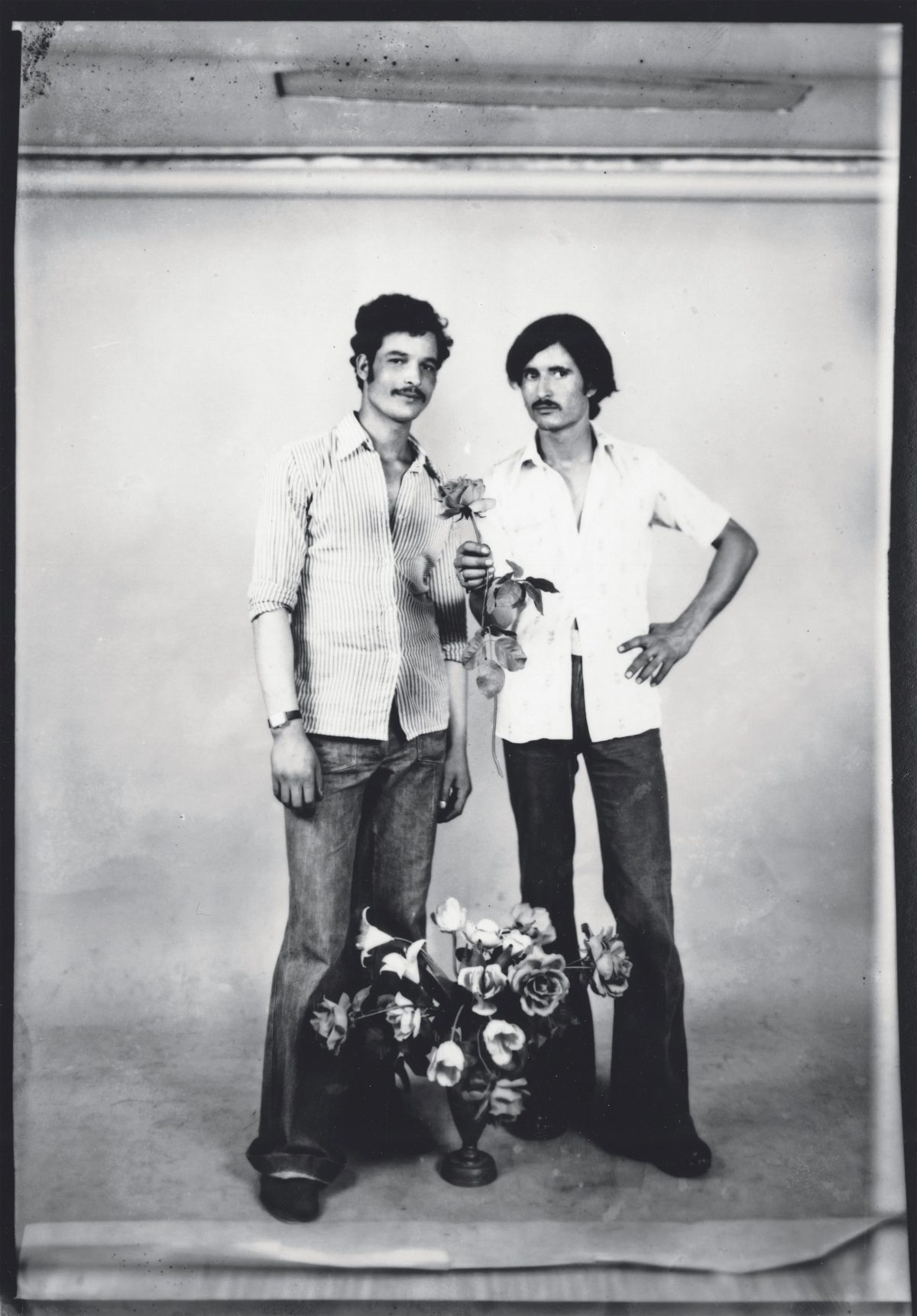

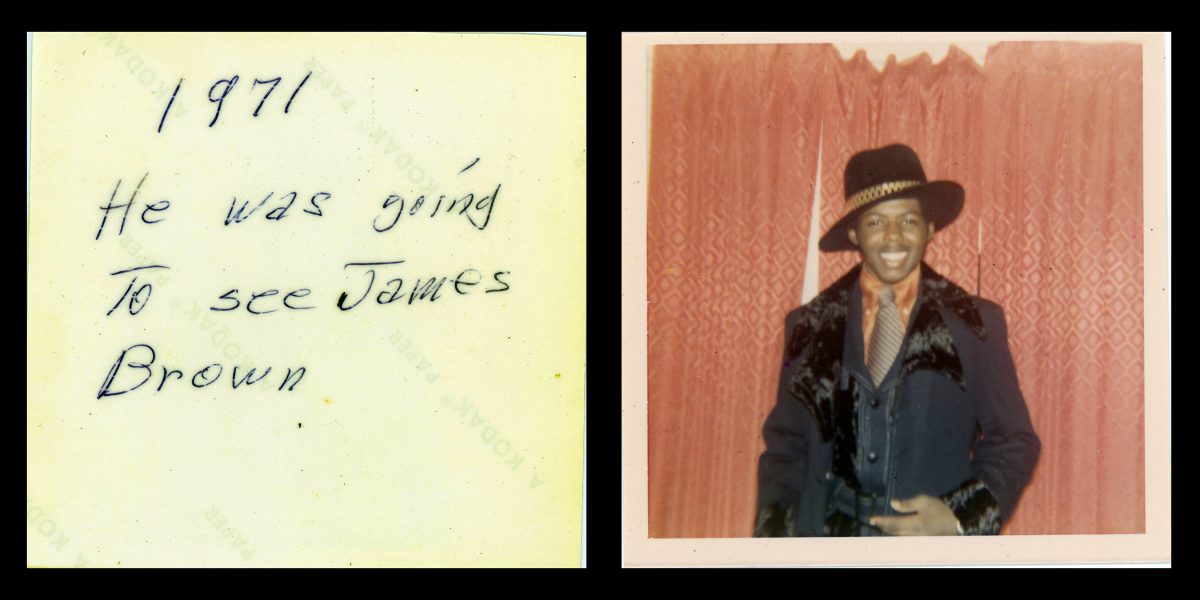

Through the work of collectors, we can step closer to image heritages that are not personally our own, and to the diverse, marginalised histories that shine through everyday photography. Through these collections, we are able to theorise our past, documented through and shaped by photography – and this is how a found archive of a Marseille working-class, neighbourhood-based photography studio can tell us more about the diverse societal relationships and fabulous fashion of the seventies and eighties, as in the case of Jean-Marie Donat’s Studio Rex, now on view in Paris. It is also how a digitised photography collection can shift a whole country’s visual landscape by offering free-to-use photographic material to anyone who wishes to engage with it, as in the case of Fortepan, founded by Miklós Tamási in Hungary. Everyday photography collections are often discovered through artistic, research, and academic endeavours – but the fact that the collections exist at all is thanks to the collectors themselves. There are numerous ways to collect – institutionalised, government-led, those that expose the dysfunctional elements of our society, and those that hold a mirror up to our past mistakes. Still, in this text, I would like to sing a love song to those individuals who were carried by the tide into the world of vernacular photography collecting, fuelled by their own deep interest and longing to see and discover more vernacular photography every day.

Just as with the visual material at the heart of my theory, the collectors themselves exhibit wildly different collecting habits, embracing various interests and even fixations on distinct image types. Their relationship to monetising their collections also falls along a broad spectrum of possibilities, and their efforts at digitising their collections vary greatly. Yet despite these differences, they share one essential conviction: that spending time with these otherwise fleeting photographs is a pursuit worthy of both financial and emotional investment. I am rarely one to celebrate the attitude “the man is what he possesses”, but maybe here we have something to celebrate.

When I speak of collectors, I think about various types: those who attend flea markets simply for their own pleasure; those who, driven by an unflinching interest, have built cross-Atlantic relationships and have others sending photographs to them, turning their hobby into something far more institutionalised; those who work on a non-profit model for the joy of society; and those who make a profit by selling their collections to major museums, securing their future safekeeping.

What these collectors do, in essence, is to look at the past from the vantage point of a possible future – borrowing an idea from John Berger’s essay of a similar name. Their particular gaze and interests determine what they purchase, keep, or resell, and this gaze is closely attuned to contemporary concerns, tastes, and visual culture. Personal motivations and professional ambitions also play a part in shaping these decisions. Which photograph is worth safeguarding? Which is compelling enough? Which holds aesthetic value? Each of these judgements is made by the collector alone, and it is through this process that a broad spectrum of collecting habits emerges. And what other material could warrant such varied approaches – in both decision-making and scale – if not the most diverse visual material we share: the vast landscape of vernacular photography?

The more angles we gain through small- and medium-scale collecting practices, the more faithfully our preserved visual narratives will reflect the real histories we share and have lived through. As more families part ways with their photo albums, and as cloud-based storage becomes the more convenient option for many, we need vernacular-photography aficionados more than ever. They safeguard an image heritage that is disappearing by the week, especially as older generations pass on, and younger ones develop new attitudes towards past vernacular photographs. By safeguarding the beautiful, the problematic, and the questionable alike, we secure the possibility of analysing all of it. In the long run, this allows us to decipher what has been recorded: the tangible moments we have experienced with one another and with our cameras, which remain some of the most revealing and introspective ways of looking back at ourselves.

There are numerous ways to collect; let me introduce a brief, by no means exhaustive, list of aficionados who shaped my understanding of what a collector’s mind and dedication can achieve – and whose collections served as my gateway into appreciating the figure of the vernacular photography collector. Kardos Sándor, a Hungarian cinematographer, founded the Horus Archives. This vernacular photography collection has been expanding for more than 30 years, becoming, in terms of size, the most extensive private collection in Hungary. Quoting him, he “learned a lot from amateur photographers, from the hundreds of thousands of people whom he cannot know personally.” Jean Marie Donat, the previously mentioned French collector, describes himself as a “ventriloquist” photographer and does not stop at collecting – a habit fuelled by the attitude that “the only thing to do in life is to be curious.” He also publishes titles, curates exhibitions, and co-founded the Vernacular Social Club with Lukas Birk, a space for fellow vernacular collectors and enthusiasts. Birk is also a collector and publisher, or as he calls himself, a travelling artist, archivist, and storyteller – the publisher of a long line of successful and informative titles through his publishing house, Fraglich Publishing. The French picture editor and collector of poor images, Matthieu Nicol, has a long-lasting taste (sic!) for vintage food photography, publishing several titles on the theme. At the same time, the London-based Family Museum, co-founded in 2017 by filmmaker Nigel Shephard and editor Rachael Moloney, is an archival photography project that collects and showcases found photographs through storytelling and zine publishing. Staying partly in London and moving partly to Australia on the map, the Archive of Modern Conflict – which collects material related to modern conflict – is a more institutionalised endeavour, not solely focused on the vernacular, but also helping to keep that image heritage alive through a broader scope of image and object collecting and publishing. The Australian collector, Patrick Pound, challenges notions of singular authorship by creating works that utilise found photographs and objects from his personal archives, amassing over 7,000 vernacular photographs and objects.

Meanwhile, the Mexico-based Barbara Levine and Paige Ramey, founders of ProjectB, are known for building offbeat collections and using them as the foundation of their artistic practice, which includes books, archive projects, workshops, and exhibitions. In contrast, some of their previous collections were acquired by US institutions. The New York-based Peter J. Cohen is focusing on snapshots and vernacular photographs, building one of the largest privately held collections of “anonymous” photographs in the US – and generously gifting it to major art institutions worldwide.

As I was re-reading Boris Groys’ book, “Logic of the Collection,” I came across a theory he introduces regarding fine art and collecting. Quoting him: “In our present age, serious and autonomous art is primarily produced to be collected. It is no longer conceived as part of a temple, church, or palace, as it used to be; rather, it is intended from the beginning for the isolated, autonomous space of public or private collections. As a result, today’s art production differs significantly from all other modern forms of production. All other products are intended for consumption. (…) A work of art (…) is not consumed as an object, but kept: it may not be eaten, used, or completely understood.”

As photography has long navigated the tension between art and reality, invoking this quote when considering everyday photography is far from unreasonable. Much contemporary art is created with collecting in mind, and institutional validation often positions acquisition as the most forward-looking form of preservation an artist can hope for. Consumption and collection, however, are not the same act, and vernacular photography occupies a space that touches both. These photographs were initially made for everyday use, circulation, and private meaning. Yet when we look back at them from a possible future, it is we who assign them a second life through collecting. In that shift, the consumed becomes the conserved, and the ordinary image becomes part of a visual heritage worth safeguarding.

While the politics and relationships we, as photography lovers, art institutions, and society, build with these collectors and their collections are in formation, it is fair to say that we need people to collect and safeguard the vernacular. Safeguarding and circulating vernacular photographs remains a complex task. Ethical approaches to these images are still evolving – shaped not only by the rise of social media but also by the particularities of each photograph and each collection. These individual encounters are what refined our understanding and deepened our appreciation of vernacular archives.

While I do not romanticise collectors, I believe we share a collective responsibility: once their work of gathering and preserving has been done, we must take the next step – the showcasing – with the highest possible care. This means learning from the methods of thinkers such as Ariella Azoulay and Zeynep Gürsel, and bringing academic knowledge into dialogue with the attentive, practitioner-led ways of looking that vernacular photography demands.

We chose our institution’s name, the Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography, in line with the idea that we are all reflected through this photographic material – each in different ways, shaped even by the hiatuses created through the cameras available to us, the time we had to make images, and the financial circumstances our predecessors lived within. Roland Barthes, in his often-quoted 1980 book, Camera Lucida, uses the phrase “eidolon” to refer to the “phantom-image” of the subject that was photographed. In his own words: “The Spectator is ourselves, all of us who glance through collections of photographs-in magazines and newspapers, in books, albums, archives… And the person or thing photographed is the target, the referent, a kind of little simulacrum, any eidolon emitted by the object, which I should like to call the Spectrum of the Photograph, because this word retains, through its root, a relation to “spectacle” and adds to it that rather terrible thing which is there in every photograph: the return of the dead.” We wanted our institution’s name to reflect our goal: to look back at ourselves through the opportunities provided by everyday photographs.

While amateur photographers once captured fleeting moments out of curiosity, obsession, or joy, collectors today ensure that these fragile visual records endure. By safeguarding this image heritage in their own time, they enable researchers, artists, and enthusiasts to work from materials that might otherwise vanish into obscurity. Collecting is not merely preservation – it is an act of connecting people, places, and histories that official narratives frequently neglect. This conviction is at the heart of Eidolon Centre’s founding: to create a space where collectors, academics, artists, and lovers of vernacular photography can meet, share, and collaborate, affirming the profound cultural value of these everyday images.

Róza Tekla Szilágyi is the co-founder and director of the Eidolon Centre for Everyday Photography, the world’s first institution dedicated solely to showcasing, analysing, and appreciating everyday photography and banal imaging, in both its past and present forms. She lives and works in Budapest, where she has been publishing in national and international art magazines and journals since 2012, and has acted as editor for several printed publications, including the Arles-shortlisted Fortepan Masters – Collective Photography in the 20th Century – Selected by Szabolcs Barakonyi and József Csató’s My Favourite Place Is The Garden in My Head.