One of the least discussed topics around the eclipse of analogue photography, by digital, is the impending loss of the photographic object.

Maybe it hasn’t merited much mention because (as Geoffrey Batchen reminds us ) there is a widespread tendency to suppress what a photograph is in favour of what it shows. Even the most sophisticated discussions around photography centre on the image, overlooking what else it might be.

The activities of Found magazine are interesting because they bring the materiality of the photograph powerfully into focus, just as the trend seems to be for its dematerialisation.

Found magazine was established in the USA in 2001 for collectors of objects trouves. Its website asks for, “love letters, birthday cards, kids’ homework, to-do lists, ticket stubs, poetry on napkins, telephone bills, doodles – anything that gives a glimpse into someone else’s life…” The title specialises in publishing such items but always alongside the “outsider” writing of collectors with alternative accounts of the world – whacky mysteries, strange tales and calamites (real or imagined) based on whatever evidence can be sifted from the detritus of the city’s streets and tips.

The favoured idiom is collage and found photographs are a popular ingredient of collage narratives. This is somehow fitting if you remember that photo collage started out as a domestic activity. Early family albums are instructive for showing how photographs and sometimes texts were organised into personal narratives. Among the “worthless” photographs to be found in city spaces are banal snaps or studio portraits (most of them analogue) and a good proportion of Polaroids (those remnants of the era of the daguerreotype). In scans these items yield information about what they are, not just what they show. Such abject material was banned from the Modernist archive, but is now welcome in Found magazine’s ad hoc archive, dispersed inside thousands of envelopes. Every envelope is a portable collection and inside each envelope is a missive that responds to the editors’ invitation to: “Tell us where you found [the object], which city, and any reactions of interpretations you might have.”

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

Without supporting context most photographs mean nothing (or anything). But perhaps it is better not to know anything about the facts behind an image if your intention is to co-opt it into a strange or fantastic scenario.

The collage material that is sent to the editors of Found magazine (and its sister, Dirty Found) is too divers to constitute a style, but contributors aspire to make the material tell a good tale. A sequence of snapshots of a seated man in underwear is transformed once we read that it dropped from, “inside of a 1950 copy of ‘The Dictionary of Underworld Lingo’…”. Two cheesy home-made Christmas cards, adorned with eager smiling faces, become memorable with the addition of the caption: “Misdelivered Christmas cards”.

These examples demonstrate the susceptibility of photographs to text but also help us to see the photograph as something beyond an image; as a vulnerable thing with a unique social biography.

Elizabeth Edwards argues that the treatment of photographs is in many ways analogous to that of relics (such as those of a saint) and that both can be understood through social biography. Like the relic the photograph follows a “path of ritual experience” that begins when it is deemed significant both for its authenticity – as “traced off the living” – and for the access it can provide to a real or imagined past. From the ordinary space of secular symbols it enters into the “spatially non-ordinary” for a while, where it is stored carefully in its album or gilt frame. As a sacred symbol (usually connected with death) the relic has entered a special place where it is cherished. But it returns to the ordinary when the owner has no more use for it. The Dumpster, yard sale or junk shop can be thought of as the final stage of the ritual cycle for private photographs that have been abandoned by those who gave them meaning and removed from their privileged places.

Once rescued, these objects acquire new symbolic currency when placed inside the virtual Wunnerkammer of the Found magazine archive. Here they exist to be displayed and described as treasures from the gutter, trophies of strange encounters and fetishistic objects. For some letter writers photographic objects are viewed as uncanny material parts of their sitters, or surrogates.

This theme is also present in a strand of fiction that taps into old superstitions surrounding “living pictures” and “voodoo”, that trades on the recognition of the conventional photograph as type of “trace” or deposit of the real. Susan Sontag recalls such a passage in Jude the Obscure where Jude is devastated to discover that Arabella has sold a maple picture frame that still contained his photograph. By thoughtlessly disposing of Jude’s photograph Arabella has (symbolically) disposed of Jude and demonstrated to him, “the utter death of every sentiment in his wife”. Nearer the present day the film 24 Hour Photo concerns a disturbed man who works in a processing lab. The power of the stalker is symbolised by the presence, in his apartment, of the photographs he steals from vulnerable victims. From these accounts we see that photographs have a reputation as sinister surrogates for their sitters. The materiality of the photo is emphasized when it is portrayed as something that can enter or leave lives unexpectedly and can be handled and possessed.

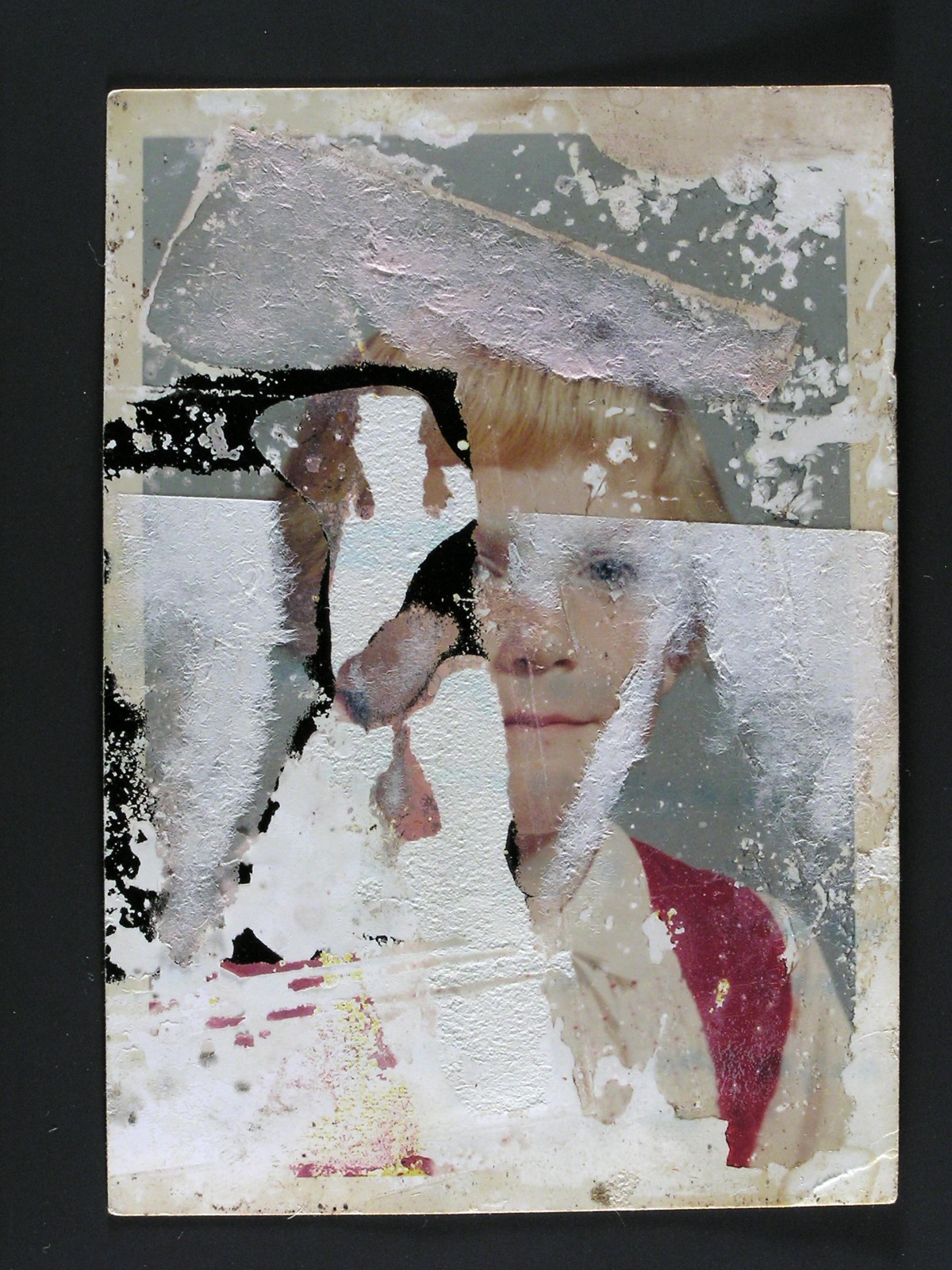

In the Found magazine scenarios photographs are usually encoded interfaces between different worlds of meaning. The signs of wrenching and violence that accompanied their transit from a previous world are rendered visible and tactile in marks and traces that can fuel the fantasies of contributors.

Two letters to the editors equate damaged photographs with absent bodies. The first, from Josh Burker, concerns a chance encounter with a portrait of a charming oriental bride. In a timeless soft focus three-quarter studio shot the subject clutches flowers. Josh knows nothing about this woman but chooses to construct a “weird” fantasy about her life from the material evidence. The portrait was discovered face-down on a dirty street in China Town, San Francisco and might suggest a “Chinese bride” (the title he gives the picture). A series of negative haptic signs – including a damaged cheap card frame into which her picture is inappropriately inserted, but chiefly a “scuff” on the emulsion – undermine the “truth” of the image as an icon of nuptial bliss. “Was she a Chinese bride ordered by some westerner, or was she the bride of somebody who had immigrated (sic) to the United States, leaving her behind in China? Why had the person discarded the photograph; had the divorce soured, or was this a loan (sic) reminder of his lover accidentally dropped?” Josh asks if the picture of the bride got, “scuffed because the person [the imagined husband] hated her.”

Another letter comes with the two fragments of a torn-up photo booth strip representing a sequence of shots of a smiling adult woman and a toddler. While there may be an innocent explanation, the finder, Whitney La Mora, chooses a dark one: she expresses dismay that these “happy pictures” were ever discarded.

Both the violated portrait of the bride and the torn photo booth uncannily embody opposites: happy and violent would appear to be inscribed, respectively, in the chemical and the material traces.

Sontag understood why photography might be considered as a “magic” form of representation because it somehow restores the unity of image and referent that once existed in “primitive” societies. Recognition of the symbolic connections between a photograph and its referent can make “modern primitives” (her term) want to protect pictures of people they know from damage or destruction. When finders rescue an object, apparently fearful of its destruction, they are concerned for the referent. Justin, who found a very intimate snapshot (of a dead woman reclining in a coffin) abandoned, “in the taxi lane of the Kansas City airport”, believes he has saved some sort of human remains. He informs us that: “it just seemed wrong to throw [the picture] away or drop it back on the ground.” He pleads with the editors to publish it so that the deceased woman, “might achieve a type of immortality or something.”

These few examples from the Found magazine archive do not begin to convey its richness, diversity and complexity. Contributors aspire to publication for a number of reasons: for instance, to be recognises as part of a group of collectors, but also to demonstrate their narrative skills. Mieke Bal has noted that, “all narratives sustain the claim that ‘facts’ are being put on the table…” then goes on to explain the difficulties. Because nothing published in Found’s titles can be authenticated (or disproved), it would be unwise to take any letter at face value as an open and honest account of the circumstances surrounding the discovery of photographs. But perhaps the authenticity (or lack it of) of these “life writings” matters less than the popular attitudes they espouse as digital photography is rapidly replacing analogue. A browse through Flickr.com tells us that picture taking is popular, fun and gets you friends. Found magazine (and the website, www.foundmagazine.com), by contrast, seems to say more about the photograph as fetish, an object of desire and mystery.

One of ways the editors of Found’s titles like to mediate the material in their ad hoc collection is to make it available for exhibition. When the prints are pinned to walls visitors can experience what makes them such compelling sources for narrative and fantasy. Looking at the relish with which exhibition visitors inspect these objects it is impossible to overlook the fact that digital technology, while bringing so many hidden things to sight, refuses to submit them to the scrutiny of our senses. Touch, we’re told, dramatically annihilates space and time, giving the person who handles an object a sometimes overpowering sense of connection with previous owners.

There are parallels between the ascendancy of the digital image in the early 21st century and the opening years of the last century when assembly line photo processing was making the old hand-coated processes obsolete. One early 20th century commentator looked back with wonder to the heroic days of the daguerreotype (a highly detailed decorative image that invites handling) and wondered if its passing meant, “the days of mystery in photography were ended”.*** This proved to be premature (the old magic lingered on as Sontag noted). But perhaps some of the mysteries will really vanish when we can no longer handle photographs that were tokens between lovers or family keepsakes. For it seems that even rejects are becoming as rare as the “treasures” in collections.

Just as these early 20th century commentators felt compelled to re-imagine the daguerreotype, it seems that we are beginning to think about old photographs in new and constructive ways. The world of the camera has been haunted by supersitions around “soul stealing” processes and sinister operators since its advent, and this is reflected in cultural productions that ingeniously exploit these undercurrents (including those sent to the Found titles). For a pre-digital generation of theorists, weaned on semiotics, the magic of the old photography was the unity of image and referent made manifest in silver chemistry. Because of this Barthes was tempted to ask: what would be thrown away with a photograph? “Not only ‘life’ (this was alive, this posed live in front of the lens), but also, sometimes – how to put it? – love.” There is no reason why the magic won’t re-remerge in the digital image – even the desktop file – and where it does it will always be reminder of one major difference between digital and analogue. Barthes described yellowing old photographs as “mortal” because they aged like people. By contrast, digital photographs – whose connection to a referent is always tenuous, and whose materiality is contingent – are disembodied representations. They can exist without us and may never fade.

The Found magazine archive contains much to amuse and thrill – and possibly offend – and it draws its fascinations from the old magic of the material photograph as a perceived vestige of its referent. While both the photographic and the literary worlds have still to address the presence of the photograph in fiction, it seems this archive has the makings to be a resource – perhaps where objects could be handled – that is dedicated to the photograph as a fictive object. Could it attain lasting importance because those who created it were among the last to experience photographs as tactile, chemical-smelling bits of paper; to recall posing for clunky film cameras and to imagine their pictures to be some mysterious part of themselves that left them vulnerable?

[/ms-protect-content]

Published in Photoworks Issue 8, 2007

Commissioned by Photoworks