Brett Rogers was appointed Director of The Photographers’ Gallery in September 2005 with a remit to take the gallery into a new building and a new beginning.

In her first magazine article since her appointment Rogers describes her vision for the future of the organisation.

Not long before accepting the job as Director of The Photographers’ Gallery I read an excoriating review in a Sunday broadsheet which lambasted the outgoing director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), Phillip Dodd, for imposing his radical vision on that organisation. The writer criticised Dodd for transforming the ICA into a digital place which felt ‘carcinogenic’ because he ‘divorced the ICA from tangible human passions and that exciting smell of proper human creativity’ ; added to which he had a reception which felt like a branch of Waterstones. What struck me about the article’s concluding message was that in this over-mediated culture, the arts punch well above their weight – ‘you just need to put on great exhibitions serve super coffee, get your staff to smile, then unplug the computers (because you can be a nerd at home)…’ (1)

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

Those forthright comments, by a writer and critic who is well-known for his passion and commitment to the visual arts, struck a chord with me because there is often a temptation for organisations to radically reinvent the ‘brand’ especially in a case like ours when The Photographers’ Gallery is beginning to plan its move into new premises. But is this really the right way to go? In developing my vision for the Gallery – the delivery of which remains some months off – I am determined not to skirt around the fact that there remains an urgent need to address the issue of the profile of the Gallery both nationally and internationally and (just as importantly) to examine how it engages more directly with the photographic constituency here in the UK as well as with the wider (non-specialist) public. It is clear that to remain relevant and a key player within the cultural field, any healthy organisation must re-examine its mission every decade or so. The most recent example of a similar organisation that has undergone this process successfully is Autograph. By doing this they have signalled their decision to move away from focussing exclusively on issues of cultural diversity to embracing the wider remit of human rights.

During the past decade there is no doubt that the cultural landscape within London (and the UK) has changed dramatically as far as photography (and therefore photographic galleries) is concerned. This is due, in part, to the ‘Tate effect.’ The opening of Tate Modern in May 2000 and the enormous audiences it now attracts has helped redraw the cultural map in the capital. Along with the undeniable benefit of more people participating in the social experience of visiting cultural institutions has come the need to attract them with a wider variety of accessible, popular and engaging exhibitions. Now in addition to Tate (Britain and Modern) including photography exhibitions in their programme, there are the other public spaces (Whitechapel, Barbican, Hayward, NPG) which regularly schedule major photographic exhibitions as part of their overall visual arts offer.

The reasons why a visitor to London can find a host of photography exhibitions on offer in 2006, whereas 15 years ago this was rarely the case, has as much to do with the shift within the medium itself and its appeal to fine artists – as to its inherent promiscuity. The sudden explosion of interest in photography – the frisson of excitement that surrounded the (re)discovery of the ‘document’ by fine artists – has led some commentators to conclude that “if sculpture defined British art of the 1980s then photography and video definitely did the same job in the 1990s” – when British art enjoyed a very particular position of respect and interest within the international art scene.

Having reached this point of acceptance within the art market and gallery system, I feel it is now a salient time to ensure that the medium’s ‘promiscuity’ is championed and that this new public who are thirsty to engage with photography, understand and appreciate photography’s inherent versatility through different levels of access and involvement. Unlike the spate of galleries that only present photography occasionally, The Photographers’ Gallery is uniquely placed to fulfill the ‘DNA’ test – to present the broad ‘photo-genetic map’ required for an understanding of both contemporary and historical practice through a regular series of exhibitions, public debates, talks, events and opportunities for self-directed learning. What gives the medium its particular relevance and potential to attract a wide audience is its “slipperiness” – its ability to encompass such a diversity of practices – from vernacular and archive images, fine art, photojournalism, reportage, advertising, fashion as well as the ever-present core of documentary which perhaps lies at the heart of its genetic code.

Its worth recalling at this point an observation that David Brittain made almost a decade ago and which has retained its efficacy ‘currently many photo galleries are fashioning themselves on the white cube of the fine art gallery. Another model is the media centre. If you look back at the early Photographers’ Gallery – here was something in between; it was a gallery which wasn’t an art gallery, yet which could give a platform to a variety of photographic work which didn’t always aspire to art. Potentially such a space is best able to deal with the slippery nature of photography, located between art and media. That special secular space of the photo gallery is gradually vanishing. Yes, it had its problems but we have learnt from them. If we needed one definitive reason for the existence of dedicated photography organisations ……..it would be that it is in their nature to raise difficult questions about the identity of photography.’ (2)

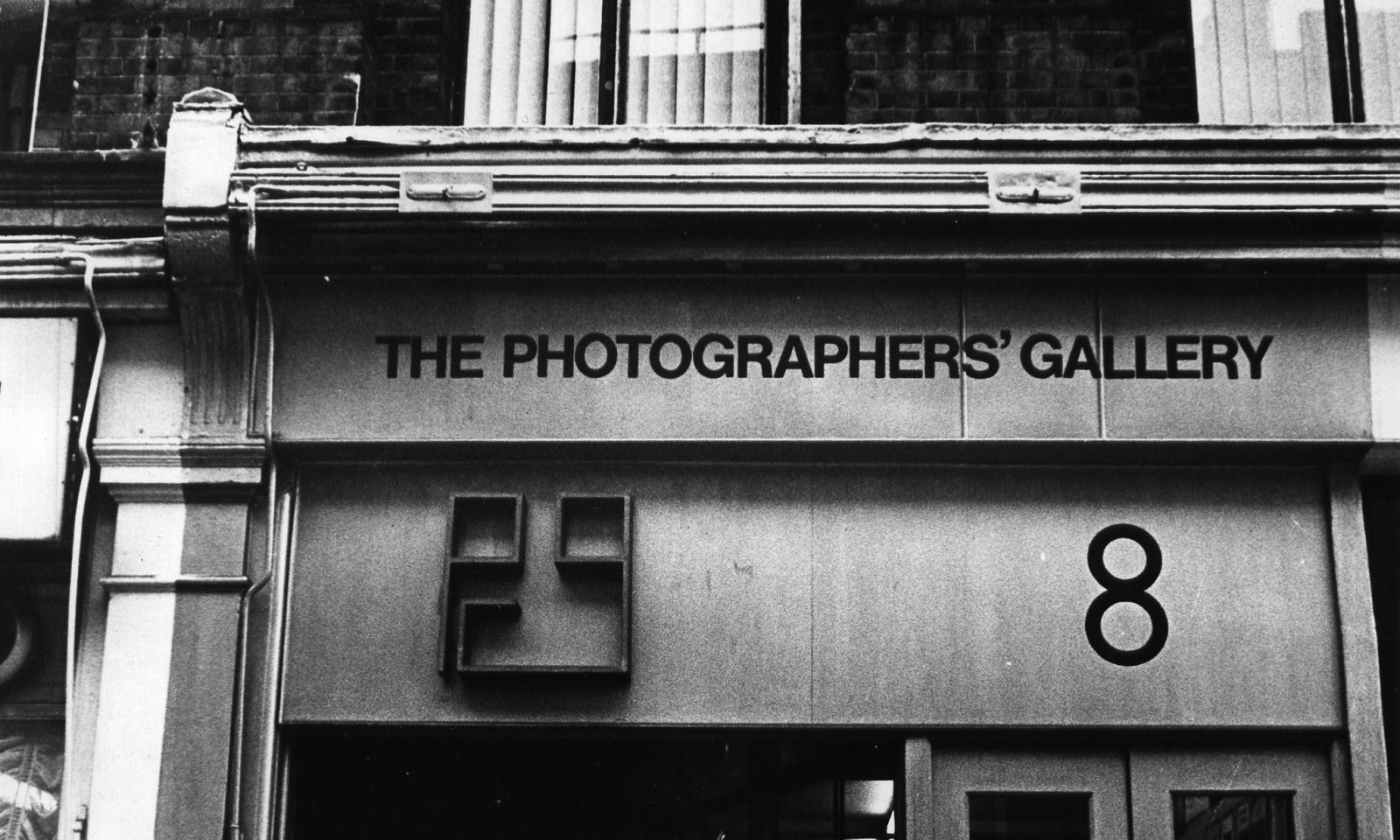

Asking difficult questions about photography as a medium has been hard-wired into the gallery since its inception. Whilst we are currently looking forward to developing the future vision of the Gallery it is also very important, at the same time, to reflect on where we have come from. This year ‘s 35th anniversary provides us with an opportunity to celebrate and reassess the aspirations and original vision surrounding the Gallery’s founding in January 1971.The fact that the founding director Sue Davies was able to elicit the support of such a wide range of champions – from the formidable Lord Goodman to the amiable Tom Hopkinson, and garner such a distinguished list of patrons as Aaron Scharf, Bill Brandt, Cecil Beaton and Roy Strong reflects the strength and depth of feeling and genuine excitement that then existed for the establishment of a dedicated photography space.

A publication which will help us document and assess the Gallery’s contribution to the broader cultural landscape during the past 35 years is being planned for later this year. Not only will it herald the Gallery’s outstanding record in introducing international figures to the UK for the first time such as Walker Evans, Lartigue, Gordon Parks, Rineke Dijkstra, Boris Mikhailov, amongst others but it will also attempt to catalogue its pioneering work from the late 80s to the present in the field of education and life-long learning. The contribution of distinguished ‘alumni’ operating either as members of staff – Dorothy Bohm, Martin Caiger-Smith, David Chandler, Gilane Tawdros, Zelda Cheatle, Kate Bush, Jeremy Millar to name a few- as well as supporters and exhibitors will also be incorporated as will the function which the Photography Prize has played in the fulfilling the Gallery’s remit.

The pivotal importance of the Prize, its role in raising the profile of photography not just within Britain but in Europe, cannot be underestimated. Looking back over the first decade of the Prize, now called the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize, it is difficult not to be struck by the consistency and quality of the shortlist and impressed by the broad generational mix of international practitioners representing such a diverse range of practice. Concentrating solely on this year’s nominees, there are the images reflecting the measured though compressed anger of the veteran American photographer Robert Adams sitting alongside the observant documentary of Yto Barrada, the liquid intelligence of Alec Soth and finally the immersive participatory video of Phil Collins. What could better signify the buoyant state of the medium and the crucial place photography holds in shaping our future? Perhaps given that we tend to overlook the fact that ‘ the arts do punch above their weight’, continuing to exhibit work of this quality, together with serving ‘super coffee’ and ensuring the staff occasionally smile could signal a fairly positive start to answering some of the big questions we are now facing.

(1) Waldemar Januszczak Sunday Times Review section May 2005 p 6-7

(2) Creative Camera editorial October 1998 [/ms-protect-content]

–

Published in Photoworks, Issue 6, 2006

Commissioned by Photoworks.