Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns met for the first time one winter night in 1954 on the corner of Madison Avenue and Fifty-Seventh Street.

Johns was walking home from his job at the Marlboro Bookstore where he worked the night shift, Rauschenberg was with his friend the young artist and art historian Suzi Gablik. At that time Gablik was one of the few people Johns knew in New York City and she introduced the two men.1 Given the time of that meeting late in the year, it is likely that Rauschenberg’s powerful photographic portrait of Johns from 1954 was taken early on in their friendship. In shirt and tie and a loosely fitting overcoat that suggests his leanness, Johns’s face is angled slightly towards the camera half in shadow, he has an embattled look, vulnerable but sharply intelligent. It is a portrait that betrays the photographer’s affection, and is evidently one of the photographs of Johns that Rauschenberg recalled later could ‘break your heart’. ‘Jasper was soft, beautiful, lean and poetic. He looked almost ill – I guess that’s what I mean by poetic’2. But, given their subsequent relationship, we might also be tempted to read a tension in this arresting picture: the slight look of discomfort, the uneasiness of the shy subject that suggests a meeting of opposites. And maybe there’s a sense of doubting, too, in that look, something almost reproachful that tends to reinforce what we have come to understand about the artists’ respective characters and the varying paths of their work. It is Johns, after all – cool, reserved and complex, developing an intensely thoughtful art of formal economy – whose reputation has endured and who seems so much more in step with our image of the serious, idea-driven artist of today.

In a telling summary of Rauschenberg – more outwardly engaging, energetic and impulsive, and by five years the older artist – Johns has said: ‘To me he seemed amazingly naïve, but he functioned in ways I couldn’t. Bob assumed that other people would support what he did, for one thing; I assumed I would have to do mine in spite of other people.’3 It could explain that look, and the attraction of opposites perhaps: on the one hand an art flowing from easy confidence, while on the other something more self-consciously hard-won, an art founded on rigour and perseverance.

Although the appeal of his expressive art has waned – the ‘sensual excessiveness’ that ‘jarred’4 so much with Johns, so alien now to the ironic landscape within which the viability of contemporary art is measured – the scale of Rauschenberg’s impact on the course of American post-war culture is undiminished. For one thing his work and his presence in the art scene 1950s New York is now seen as pivotal to the development and understanding of what came to be called post-modernism. Although largely misunderstood at the time, and shunned by the high priests of modernism – the critic Clement Greenberg didn’t mention him in print until 1967 – Rauschenberg’s work created a precious break in the hard line of modernist orthodoxy, introducing new kind of art and a new sense of what an artist might be. And then there is the evidence, which is more open to matters of taste, that Rauschenberg produced some of the most breathtaking art of our last century, an art that, especially during the fifties and sixties, put photography centre stage, giving ‘exquisite substance’ to the ‘interference and visual static’5 of a society increasingly under the spell of the mass media and its vast multi-faceted mirror of photographic images.

In fact, from 1949 when he first took photography classes at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, photography was a vital factor throughout Rauschenberg’s career, and was decisive to the moment, around 1954, when, as Leo Steinberg said, he invented ‘a pictorial surface that let the world in again’6. This was the moment of his ‘Combines’, a term that meant literally combining painting and sculpture, but one that also usefully reflected the works’ unprecedented combination of diverse materials. Now those groundbreaking works have been brought together for the first time in a large touring exhibition organised by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and shown recently at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The show is a timely opportunity to reassess Rauschenberg’s importance and to think more about the place of photography in that momentous work.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

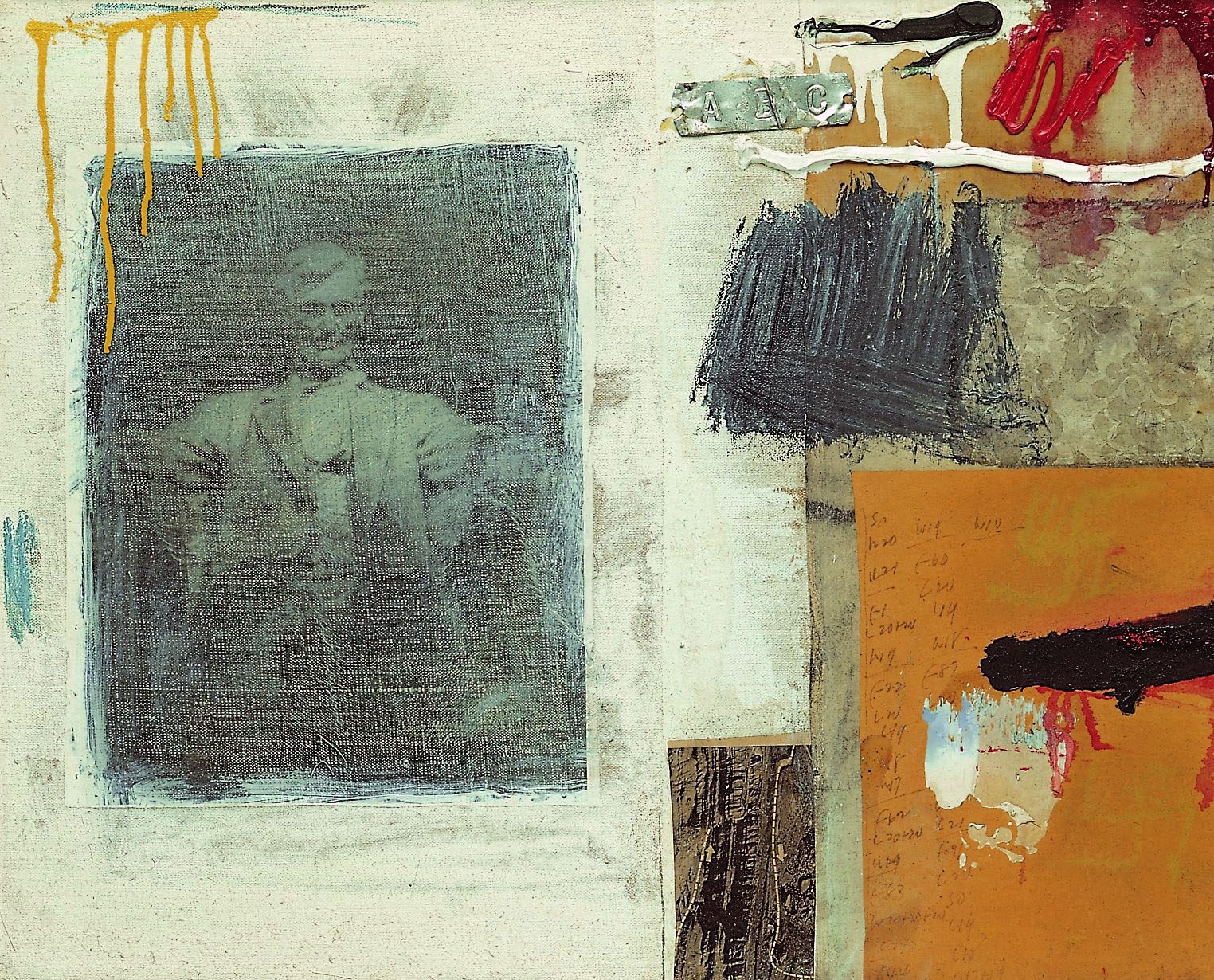

On checking through the useful exhibition history of individual Combines in the new exhibition’s catalogue, it is surprising to find just how small a percentage of this great body of work from roughly 1954-62, has been shown regularly since. The last time they appeared in any numbers in Britain (about nineteen as far as I can tell) was as part of a large Rauschenberg retrospective that came to the Tate Gallery in 1981. For the most part the Combines have been represented internationally by key works that have in the process become more well-known, Bed (1955), Hymnal (1955) and Canyon (1959), for example, are among the most exhibited and have come to stand for this period along with others that are also frequently referred to, such as Rebus (1955), Odalisk (1955/58) and Monogram (1955/59). These are some of the most striking and iconic of all Rauschenberg’s works and are now familiar from books and catalogues, but in general the specific qualities of the Combines do not fair well in reproduction. They are works that have to be experienced; even as wall-based pieces they project outwards to inhabit space, many playfully so, inviting the viewers’ interaction. But then they withdraw back again into overlapping layers and details that require close inspection and reading. And there is a lot to be read. The Combines are intimate inventories, homages to the ordinary and apparently inconsequential, to the passing debris of our lives – objects, clothing, photographs, fabrics, junk – collected and then collaged onto the picture surface. Areas of paint – marks, smears and drips – together with pencil scribblings of the same order, complete the layering and play off the structure like a form of crazed notation. The effect, especially in the earliest Combines, is chaotic and unrestrained in its merging of painterly experience from Abstract Expressionism with more ‘imagist’ poetics, like those of that earlier constructionist Joseph Cornell, whose work Rauschenberg admired. The Combines declare the terms of their making openly. Reading the catalogue description of a work such as Odalisk is like looking through that work into the artist’s studio, a new kind of artist’s studio for 1954/55: ‘oil, watercolour, pencil, crayon, paper, fabric, photographs, printed reproductions, miniature blueprint, newspaper, metal, glass, dried grass and steel wool with pillow, wood post, electric lights, and rooster on wood structure mounted on four casters.’

Predictably there has been much critical debate about the exact nature of Combines’ significance7. What seems to hold true though through this debate, and what was genuinely new in art, circa 1954, is that these beguiling works offer no sense of unification either as objects or as viewed experiences. Instead they are full of internal divisions and paradoxes, slippages and mismatches of construction, deployment of materials, spatial plays and apparent meaning, all signs; it has been said, of their nascent post-modernity. But the temptation to see the works as wilfully random – as, following John Cage, many commentators have preferred to do – is to deny the deftness of their making and to be blinkered to the repertoire of repeated motifs that come in and out of focus throughout this period of Rauschenberg’s work. Thomas Crow, looking closely at the works themselves, at their complex and often contradictory order, and at their iconography, has argued recently for a more open reading of the works, one that recognises their formal accomplishments, their weaving of biographical threads and the artist’s developing sophistication as an allegorist. For Crow the Combines release, ‘a universe of migratory symbols’, ‘…a proliferation of ungoverned signs that (Rauschenberg’s) older artist-peers had trained themselves to keep at bay.’8 Some of the chief gravitational forces in this universe are photographs and photographic reproductions, whose very materiality as objects – in direct contrast to the de-materialised flatness of the artist’s later silkscreen paintings – defines their radical presence on the picture surface.

The photographs in the Combines are mostly found images or reproductions cut from newspapers and magazines, but occasionally Rauschenberg’s own photographs turn up and in the earlier works old family photographs appear with all their autobiographical inferences. The dominant and persistent rectangular grids of the works, which these pictures in part define, have usually been accounted for with reference to art, a well-worn journeying back through the geometric and architectural forms of modernism to the cubist model. But another source, literally more close to home, and one that has been played down in studies of Rauschenberg, is the Combines’ echoing of the domestic sphere, its rooms, panelling, furnishings, decorative schemes and its pictures. Leo Steinberg, perhaps unintentionally, suggested this when he invoked a range of domestic and artisanal surfaces – ‘tabletops, studio floors, charts, bulletin boards’ – to illustrate his invented term, the ‘flatbed picture plane’9, which he famously asserted in 1972 as defining Rauschenberg’s essential challenge to modernism. Tantalising biographical details lend more weight to the artist’s refiguring of his memories of domestic spaces. Born in 1925 and brought up in a working class household in Port Arthur on the Gulf Coast of Texas, Rauschenberg remembers regularly ‘sleeping in the living room because the two bedrooms were rented out to boarders (his parents slept in the kitchen)’10, and in an interview with the art historian Walter Hopps in 1976 the artist recalled building ‘a small sanctuary within a shared room by using crates and planks to create a dividing wall for privacy’. He decorated this space with ‘a great miscellany of things’, ‘jars, boxes, rocks, plants, insects and small animals’, and using ‘magazines or any printed material, he drew, traced, copied, cut out, pinned up and glued images together.’11

Glimpses of this form ad-hoc domestic decoration have been recorded elsewhere in photographs from the 1930s, most famously in Walker Evans FSA photographs and subsequently in his seminal book American Photographs of 193812. Whilst Evans’s photographs may depict more impoverished circumstances, it is tempting to consider a chain of association between Rauschenberg’s childhood experiences and his knowledge of Evans’s pictures which he certainly would have known from his photography lectures, by among others Beaumont Newhall, at Black Mountain College. Evans was also drawn to interior arrangements; an enthusiastic recorder and compiler of inventories he had an eye for the particular beauty of made things, and for the strangeness, too, of the vernacular and the commonplace, ‘the naïve creative spirit, imperishable and inherent in the ordinary man.’13 Yet Evans’ was a sophisticate, who, like Rauschenberg later, had made the journey to Europe and was schooled in the ways of European modernism, and it is this combination that informs the photographer’s exacting vision and that provides one template, in content and structure, for the great flourishing of the Combines.

Perhaps it came from his working-class background, which remained an important part of identity, or perhaps it came naturally to a Southener in New York, the marking out of a non-metropolitan sensibility, but it is clear that Rauschenberg’s had a strong and lasting sense of connection to a vernacular culture of making and using objects and to the private histories invested in them. Among his earliest works as an artist, his own photographs articulate those concerns, showing, like Evans, an eye for detail and a preference for ordinary things and surfaces that bear the traces of age and use. One of these early photographs from 1949 – showing the interior of an old carriage – was bought by Edward Steichen for the Museum of Modern Art in 195214, six years before the museum acquired any of his other works. By this time, photography had become firmly established in the expanding repertoire of Rauschenberg’s art, he was – at Black Mountain and in New York – at the centre of new and fluid interchanges between the arts and drew influences from a wide variety of media: painting, sculpture, film, music, dance and performance. In the autumn of 1952 he travelled with his friend Cy Twombly to Italy and North Africa and in his many photographs from this trip his preference for things that evoke what he called ‘the richness of their past’15 is evident once again. In particular, the series from a Rome Flea Market, betrays his affection for just those collisions of everyday things, partially abstracted out of context, which would later serve to structure and /or be impressed upon the surfaces of his Combines. Yet, if these pictures rehearse the form and content of the later works they also begin to appear supplementary to the startling collages and three- dimensional works, notably the Scatole e Feticci Personali (Personnel Boxes and Fetishes) – some of which also include photographs – that Rauschenberg made in Italy.

By the time photographs reappear in 1954, worked into the encrusted surfaces of his Combines, there is a sense that Rauschenberg had finally found a form that seemed to unite his various artistic impulses and give free reign to his restive imagination. Rauschenberg’s marriage to Susan Weill had ended in divorce in late1952/53, and the early Combines appear, simultaneously, as an outpouring of creative stimulus and emotional turmoil, laced with references to his past and the recognition of his bisexuality. In the free-standing Untitled (1954), for example, amongst the dense montage of photographic images, a portrait of the artist’s young son Christopher is set above a pasted note in a child’s hand that reads: ‘I hope you still like me Bob cause I still love you. Please write me back love love Christopher.’ Below this is a photograph of lone man with his hand to his head, identified later by Rauschenberg as ‘a man awaiting execution in Texas’16. As the Combines progress, photographs help to conduct the less literal thematic connections and allegorical systems that, as Thomas Crow has suggested, ‘contrive to disperse the self – and also the objects of the self’s desires – into an array of provisional substitutes.’17

Photographs take their place in the Combines’ messy order as objects but their role is ambiguous. They are both cohesive and disruptive: on the one hand binding those thematic threads and supporting the works’ structural grids, while on the other acting as images by puncturing the layered material surface with pockets of illusory space (something which may have led to the artist creating actual holes in works such as Gloria (1956)). Rauschenberg’s newspaper and magazine photographs are mostly understood as one of the ways in which he ‘let the world into’ his work. But as well as signs of ‘outside’, newspapers and magazines also have a strong domestic place, both as reading matter and as decoration. In the earlier Combines, where photographs are more prominent, they tend to reinforce rather than contradict those works’ dynamic but oddly ‘interior’ spaces. Later, when photographs fade from view, making way for lettering, signage, more gestural painting and sculptural form, the street and ‘what was going on outside the window’ of Rauschenberg’s studio is a more solid and emphatic presence.

The art historian Brandon Taylor has suggested that, ‘ Collage…allows us to see that it is somewhere in the gulf between the bright optimism of the official world and its degraded residue, that many of the exemplary, central experiences of modernity exist.’18 However, there are few hints of a bright, official world in the Combines’ by turns melancholy and joyful ‘secret epic’. Rauschenberg liked to think of himself as a reporter, but the sense of time and place in the works is indeterminate, as much to do with the pre-war American culture of the artist’s childhood than they are with 1950s New York. The Combines are works in which, during the processes of selection and making, the artist prioritised the aged and angled the present towards the past. Rauschenberg’s photographs are the discreet ambassadors of this effect. They signify an externalisation of memory, a collective, fading connection to past; and as media images, they reinforce a further sense of disconnection to abstract events that can only exist for us as symbols. Rauschenberg often veiled photographs in the Combines with gauze or washes of paint, to further fade their presence but also perhaps to shroud them and put them out of reach; keepsakes beyond touch.

Rosalind Kraus once said: ‘In Rauschenberg’s work the image is not about an object transformed. It is a matter, rather, of an object transferred. An object is taken out of the space of the world and embedded into the surface of a painting, never at the sacrifice of its density as material. Rather it insists that images themselves are a species of material.’19 But while they retain their materiality the various ‘images’ of the Combines do undergo a radical transformation in becoming part of Rauschenberg’s work. For example, items of clothing are fairly constant elements of the work, and as direct surrogates for the body they are among the most poignant points of physical connection for the viewer. But they are like long lost garments making a surprise return, maybe found on a road: soiled, flattened and hardened by exposure. The clothes, like the other object-images of the Combines are not degraded but embalmed by Rauschenberg’s glue and paint, caught in a state beyond use or usefulness, oldened within the dimension of the work, they gently but insistently restate that reminder of transience, the memento mori.

[/ms-protect-content]

Published in Photoworks Issue 6, 2006

Commissioned by Photoworks