Photoworks Writer in Residence, Angelina Ruiz Alper charts a course through the 2024 Photography+ graduates’ work, and its engagement with identity and place.

From issue: #24 The Graduate Issue 2024

In Why People Photograph, Robert Adams writes: “At our best and most fortunate we make pictures because of what stands in front of the camera, to honor what is greater and more interesting than we are. We never accomplish this perfectly, though in return we are given something perfect – a sense of inclusion. Our subject thus redefines us, and is part of the biography by which we want to be known.”

Photography plays with space, place, time, identity and our sense of self. A means of expression and healing, it can provide an opportunity to speak in a world that might otherwise not hear our voices. To be heard is to be seen, to be loved; by sharing our love of the lens, we can share our unique perception of the world.

Photographer Seok-Woo Song captures the passage of time and the wonder of growing older in his Wandering, Wondering, creating images filled with space, in which humans are harder to find. His shots make us feel alone in an environment that seems otherworldly, and much bigger than us. Song’s images are also quite grandiose, often depicting huge city skylines, or coastlines with an expanse of water. Transported into these places as viewers, it’s hard to know whether they exude the mundane feelings of reality or a dream. Either way, things feel strangely familiar.

Understanding the place around us is not just about what exists, but also the people existing there. Murray Ballard explores rural life in Salento, Italy in his work Ghosts in the Field, and has documented the area over the last decade. Ballard’s images depict the changing town of Puglia as it slowly becomes a tourist destination; through his viewpoint we see what’s left and the locals, sometimes disengaged with the camera, other times staring with tired eyes. Ballad’s work also uses color and shape as a means of connection, showing subjects, both human and man made, mirroring each other.

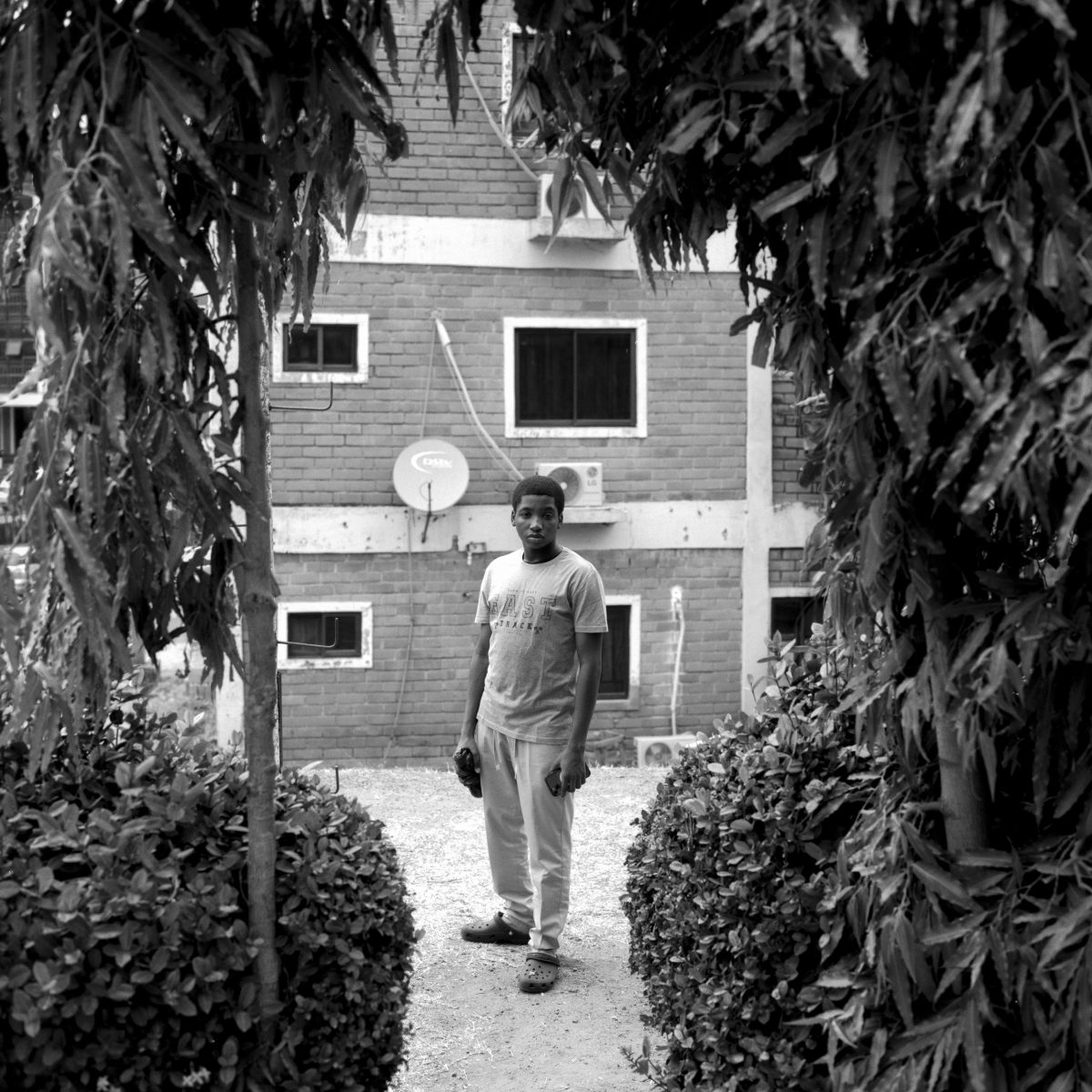

When we think of connection, family often pops into mind, and more broadly the idea of home. Home can simply be something that’s a constant, like Puglia for Ballard or, for others, familiar faces and memories – whether they’re good or bad. Photographer Mohamed Hassan uses photography to speak of his complex early years in Our Hidden Room, juxtaposing images of his father with shots of his home country, Egypt, and the diasporic community in which he now lives in Wales. Exploring his own identity, and understanding his father’s, he works to dissect the human experience.

Hassan’s work reminds us of both memory and trauma, of how our formative years stay with us for a lifetime. As we make sense of our childhoods, we give ourselves the opportunity to understand and heal, and share that process with those around us. Working through our ideas of home, we can realise we are all searching for something, longing to make peace with our own existences.

Amin Abdulrahman’s series, Is Anyone Home? explores grief after the loss of his childhood home, and the fact he’s now forced to rely solely on memories of this space. After spending most of his life separated from his extended family, Abdulrahman questions what is necessary to make a home. Is it about the physical location or the people who dwell there? He utilises images of the home, both exterior and interior, as means of preserving what’s left. Like a visual time capsule, his work offers a solution to the fear of losing recollections.

Ideas of home and family are inexplicably intertwined; we are only human after all, wanting places to feel safe and lay our heads. At our lowest we can find comfort with the ones who know us best, those with whom we can be vulnerable. Photographer Emily June Smith uses portraiture of her family to recreate challenging moments from her past, from a childhood in which, as a neurodivergent individual, she was sometimes stigmatised and isolated.

Her series A Dissonant Past Unmasked recreates scenes in which a family works to understand and cope with a child dealing with emotional regulation, juxtaposed with the artist’s own stresses and discomforts. Smith tries to convey the overwhelming feelings that accompany her day-to-day, as well as her ongoing masking of symptoms. The images show her struggles to conform to an insensitive and judgmental world.

Pressure to uphold societal standards about how we walk, talk, and present ourselves starts at the earliest points in our lives. We’re instructed to behave a certain way, to fit in as well as possible. Smith felt pressured to conform to a neurotypical world; photographer Quincey Spagnoletti explores similar pressures around womanhood. In Home Studio she employs large sets with dollhouses, mannequins, and photographs of her younger self, plus a disembodied subject which seemingly exists as nothing more than a prop. Spagnoletti is unlearning all she was taught, and encouraging us to question what’s expected of women.

Using the body as a prop in photography is not uncommon, and can function as a way for an artist to take control of their images and how they’re perceived. Madeline Brunnmeier explores this through her series Gensalten, photographing people alongside their belongings; in each case we see the subject’s body, engulfed in a cacophony of clothing and accessories, faces barely visible. Brunnmeier anthropomorphises her creations, fashioning new beings from each human. Her subjects are of different ages and walks of life yet all become sculptures, carrying the weight of their own self expression and identity both physically and mentally.

Brunnmeier’s images express something about identity and social norms through clothing; Spagnoletti does something similar around womanhood. Photographer Isabella Madrid combines the two, touching on the objectification of women but also reclaiming this narrative. In her work Buena, Bonita y Barata she delves into the portrayal of Colombian women, who are often over-sexualised at a young age, and encouraged to have cosmetic surgeries.

Madrid touches upon her experience growing up in Colombia, and perceptions of her body beyond her control; she blends nude and semi-nude portraits with backgrounds and patterns typical of the Y2k era, and a “cam-girl” aesthetic. Her appropriation of her own body successfully commands ownership, working to snuff out the male gaze. Madrid makes us question who and what the female form exists to serve.

Throughout history, we’ve seen exaggerated versions of the human body, both hyper-feminine and hyper-masculine. It’s easy to take these understandings of the body at face value, but identity is much more than how we appear. As photographers we can challenge these notions, using the lens to expand people’s viewpoints. In his series Play Glamourous Noah Fodor explores hypermasculinity and queerness, for example, through his images as an ice hockey player.

Taking a magnifying glass to a traditionally violent sport, he studies the players’ actions, what is allowed both on and off the ice. What Fodor refers to as “homoerotic behavior” – touching, slapping, and sometimes even flirting – is acceptable and even encouraged as a part of the game. But in other places these acts are frowned on, and can even put you in danger. Through his photography Fodor helps us see the contradictions, and the expectations of men when they are with other men. Using sensual lighting and objects such as jockstraps and mouth guards, he points to a vulnerability within a queer gaze.

Questioning ourselves and our identity is a universal human experience, but photographers can speak of it through specific examples. Fodor explores his own queerness as he navigates a space hostile to such an identity; This Body was Carved from Stone by Africa Barrero-Alexander does something similar, through the lens of a transgender man.

Documenting the feelings that arose, both pre-and post-transition, and how the world sees him and his existence. Barrero-Alexender uses self-portraiture to navigate his sense of self, how he is ready to present himself to the world and, in his own words, “choosing to show the outside world the person I have always known myself to be”. The images in this series are primarily black-and-white, and even the color shots have a soft and monochrome scheme. This decision, whether intentional or not, allows the viewer to focus on the shape of the body, and the introspective energy of each image.

Photography allows us to capture something immensely beautiful – the expression of the human body and spirit. It provides us with the means to regain our power, while allowing us to connect with like-minded others. The camera allows us to link pieces of our past, present, and future, speaking to something bigger than ourselves. Both together and apart, our stories are all intertwined.