William Klein’s lasting legacy to photography will be his four city books New York (1956), Rome (1959), Tokyo and Moscow (both 1964).

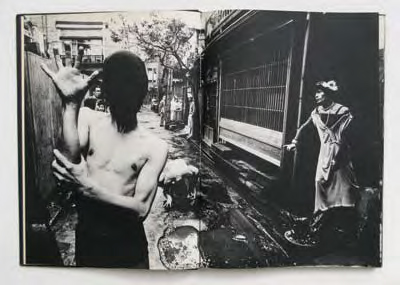

They are long out of print but with reputations growing by the year they are now more talked about than actually seen. This is about to change as republication of the first two is imminent. New York in particular is regularly lauded as one of the great photographic achievements of the last century. Its visceral imagery and endlessly inventive layout was a groundbreaking form of hyper-journalism melding the spirits of dada, Pop, abstract expressionism and counter-cinema to dizzying effect. If it had been published in America it might now be as over-celebrated as Robert Frank’s The Americans, issued two years later. Even so its influence has been considerable. A number of Japanese photographers (including a young Daido Moriyama) were bowled over by its energy and graphic daring. I think Klein got better and his later books built on the achievement of New York. Tokyo is my favourite, not least because it sees Klein returning to the city whose photographic culture he helped to revolutionize. In 1964 it was the largest city on earth and the world’s media were about to descend to cover the Olympic Games. Three years later James Bond arrived in You Only Live Twice, sealing a popular iconography for Tokyo that barely seems to have changed. Klein’s version incorporates every Tokyo cliché but in pushing them to breaking point it soars above them too.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

Klein was involved with abstract painting in Paris in the early 1950s and had dabbled with the possibilities of abstract photography (cameraless photograms and the like). But he turned to the camera more intensely in response to the chaos of the daily life he encountered in New York. His images were immersive, layered, riffing ensembles concerned less with perfect technique than the charged physicality of the chance encounter and the vectors that connect him to his subjects. He even used the anti-perspectival ‘all-over’ compositions so central to abstract painting. He was radical in the extent of his dependence on chance, on the unfolding of events before for him which he always had a part in provoking. If the imagery were not enough to justify an analogy with the modern canvas, Tokyo presents a frenetic sequence of a Japanese action painter. He’s throwing himself into his art and this is Klein’s brilliantly dense caption:

“He covers a 50-foot wall in paper, wraps his fists in rag, dips them in ink and squares off. New York school of “action painting” caught on when Georges Mathieu showed, in a Tokyo department store window [behind glass], how it was done in France. Local painters rushed to renew with traditional callisthenic calligraphy that possibly started it all in the first place.”

This kind of painting had taken the performative towards a theatre directed more at the complicit camera than the canvas. It is well accepted now that most of the ‘works’ produced by Japanese action painters were artistically worthless and junked after the cameras had captured their creation. Klein is not the neutral observer here. He’s as involved in making his imagery as the painter is with his. Klein is the prompt, the choreographer and the audience.

Before I actually saw any of Klein’s work from Japan I had read about it. I remember Roland Barthes’ particularly po-faced remark in Camera Lucida (1980): “In William Klein’s Shinoheira, Fighter Painter (1961) the character’s monstrous head has nothing to say to me because I can see so clearly that it is an artifice of the camera angle.” Barthes was never going to appreciate such exuberant playfulness for what it was. He didn’t dignify the image with reproduction in his book but it made me keen to seek it out. When I finally got to see it the photo struck me too as monstrous and artificial. But it was clear that this is also part of what photography is or can be. Klein’s particular skill seemed to lay in indulging in all that but distancing itself too. That’s not easy to do. There are plenty of complicit photographers today who will swear blind their work is ironic or subversive but it’s never for them to say.

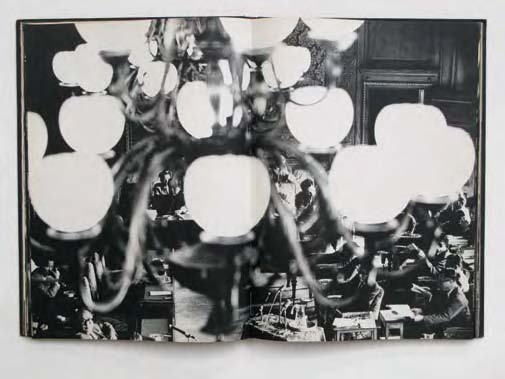

After New York and Rome Klein increased his page size so that when you open up one of the many full-bleed double spreads they are more than half a metre wide. With those dense all-over compositions in your lap you feel like you’re up close to a huge mural, not a page. I’m not sure you are going to feel that in the reproductions here but I hope you can imagine it because this is where Klein is at his best, achieving the most powerful effects with the most unlikely material. I’ve no idea why he was in attendance at a meeting of an agricultural committee or how he got so close to the ceiling but his shot through a chandelier of bored bureaucrats in session is such a photographic joy. It is difficult to look and not imagine Klein muttering to himself: “Jeeeesus this is boring! What can I do here? Ah, a chandelier!”

Klein made plenty of singular and extraordinary images, more than enough to warrant him a place in any history of ‘great Pictures’. But as with so many of the last century’s well-known photographers (Moholy-Nagy, Krull, Sander, Brandt, Evans, Friedlander, and Moriyama among them) it is becoming increasingly clear that it is on the page that the imagery was (is) at its most sophisticated. Klein’s achievement as a photographer is inseparable from his achievements as an editor, designer, writer and bookmaker.

Of all his books it is Tokyo I take down from the shelf most often. It’s so rich, so relentlessly inventive that I can never remember it all and find myself constantly surprised. It was published in America, Japan, France, Italy and Germany. I’ve no idea how Tokyo received it. No doubt it was measured against the experience of those who lived there. For the rest who saw it in 1964 I imagine it was seductive, bewildering, breathless, cacophonous, grotesque, gorgeous, informative and very intelligent. It is, still.

[/ms-protect-content]

Published in Photoworks issue 13, 2009

Commissioned by Photoworks