Originally delivered as a lecture to coincide with the Cross Channel Photographic Mission (CCPM) exhibition held during the Brighton Photo Biennial. Anne McNeill looks back on the groundbreaking CCPM, which would become Photoworks, the organisation she ran from 1995 to 1997.

“To join two countries by a tunnel is a feat of engineering and also one of imagination, as such it raises visions and provokes reactions which tell many stories, and reveal a great deal about the underlying hopes and fears of those who are to be joined.”—Neal Ascherson in Soundings: Cross Channel Photographic Mission, 1994.

Back in the early 90s, the job title curator was less common as it is now. So early on in my career I worked as a “photography development worker”, notably at the Cross Channel Photographic Mission (CCPM) . My role was primarily working with artists to support their commissions and to programme activities so it could all reach a wider audience.

Based in the South East of England CCPM’s key activity was to commission new bodies of work that documented an area undergoing change due to the building of the Channel Tunnel. And there was a French counterpart. The result was a series of inquiring critiques on the way we lived in the late 80s and early 90s.

CCPM was a bold initiative that challenged photographers. It was instigated by Pierre Devin, who was then director of the Centre régional de le photographie Nord-Pas-de-Calais (CRP). He had begun commissioning photographers to document the French side of the Channel Tunnel project; the British side, set up in 1987, became the Cross Channel Photographic Mission. Between then and 1994, the CCPM produced 24 commissions on both sides of the Channel.

The CCPM’s original 1989 mission statement read: “It is against a background of change that the photographs will work. The questions we will ask are: Is the Channel Tunnel a vital link to secure our place in Europe? Is the environmental damage worth the price? Do we want economical [sic] and political union in Europe? Is our nationality threatened? Do we wish to be Europeans?” Its commissions were eclectic, embracing all kinds of photographic genres, but they were all focused around the notion of change: the Channel Tunnel was bringing major alterations to south-east England and northern France. The first two commissions were Ken Baird and Julian Germain, whose work was exhibited in July 1990 in Folkestone. Baird took a topographical approach, revealing the physical appearance and the natural features of the ancient Kent countryside as the tunnel began to mark it. Julian Germain was at an early stage of his career and was experimenting. All his work was presented in frames that he said he’d bought in charity shops in Ashford and Folkestone as he was documenting the change in those two cities. For him, the recurring motif was barriers or borders: the security guard, the fence, the hedge, overlooking the construction of the Tunnel.

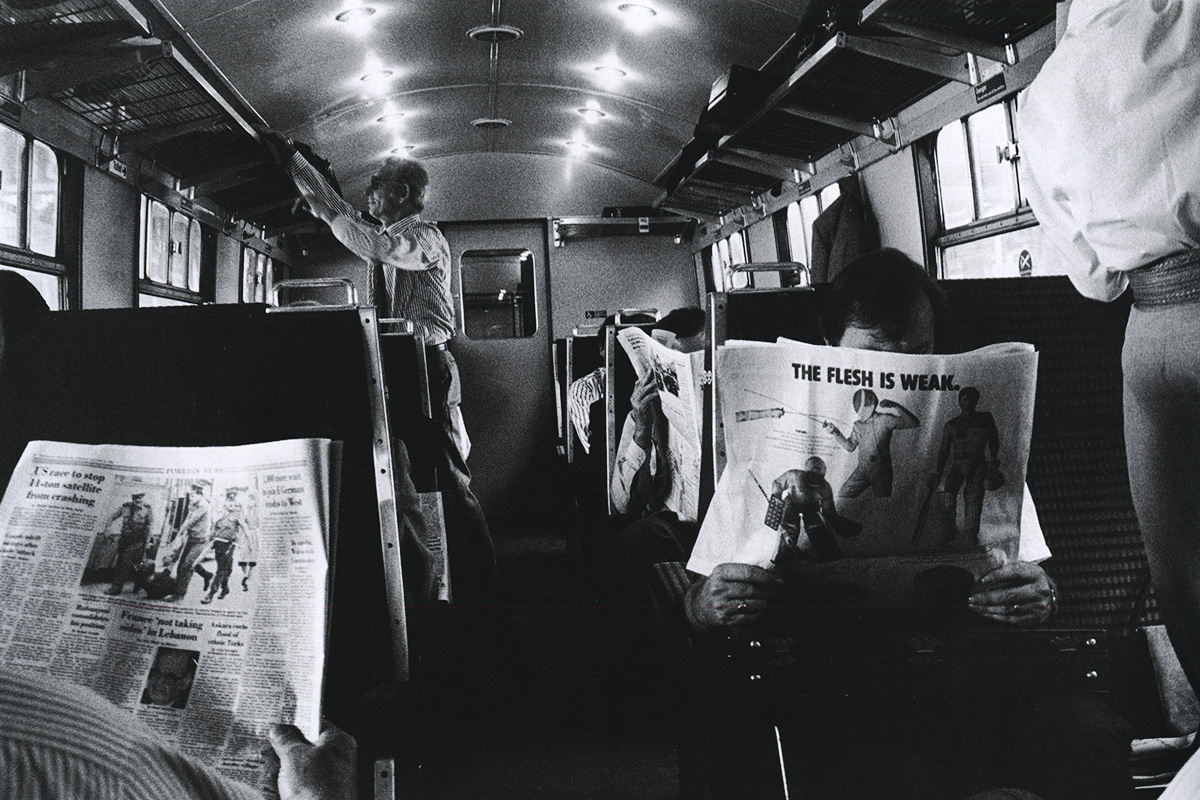

There were many approaches to photography. Janine Wiedel, for example, used a black-and-white, documentary approach and her vision of Dover showed a staunchly English place troubled by the future: lifeboat crews, baby-of-the-year competitions, and the Ann Summers roadshow at a nightclub called Image. In a similar vein, Malcolm Glover’s work, Coastal Excursions Leisure Work, looked at the coast in East Sussex.

As well as this black-and-white work, new British documentarists, including Anna Fox, Paul Reas, Paul Graham, and Martin Parr, were working in colour. Anna Fox, for example, collaborated with curator and author Val Williams on a piece called The Village. It looked at women’s roles in a rural community from different angles and was presented as an immersive installation. On the outside of a freestanding box was a series of black-and-white photographs that Anna had taken while walking around her grandmother’s village in rural West Sussex. Then when you walked into the box and were submerged by images of different women and people in the village as projected as slides that filled the entire box.

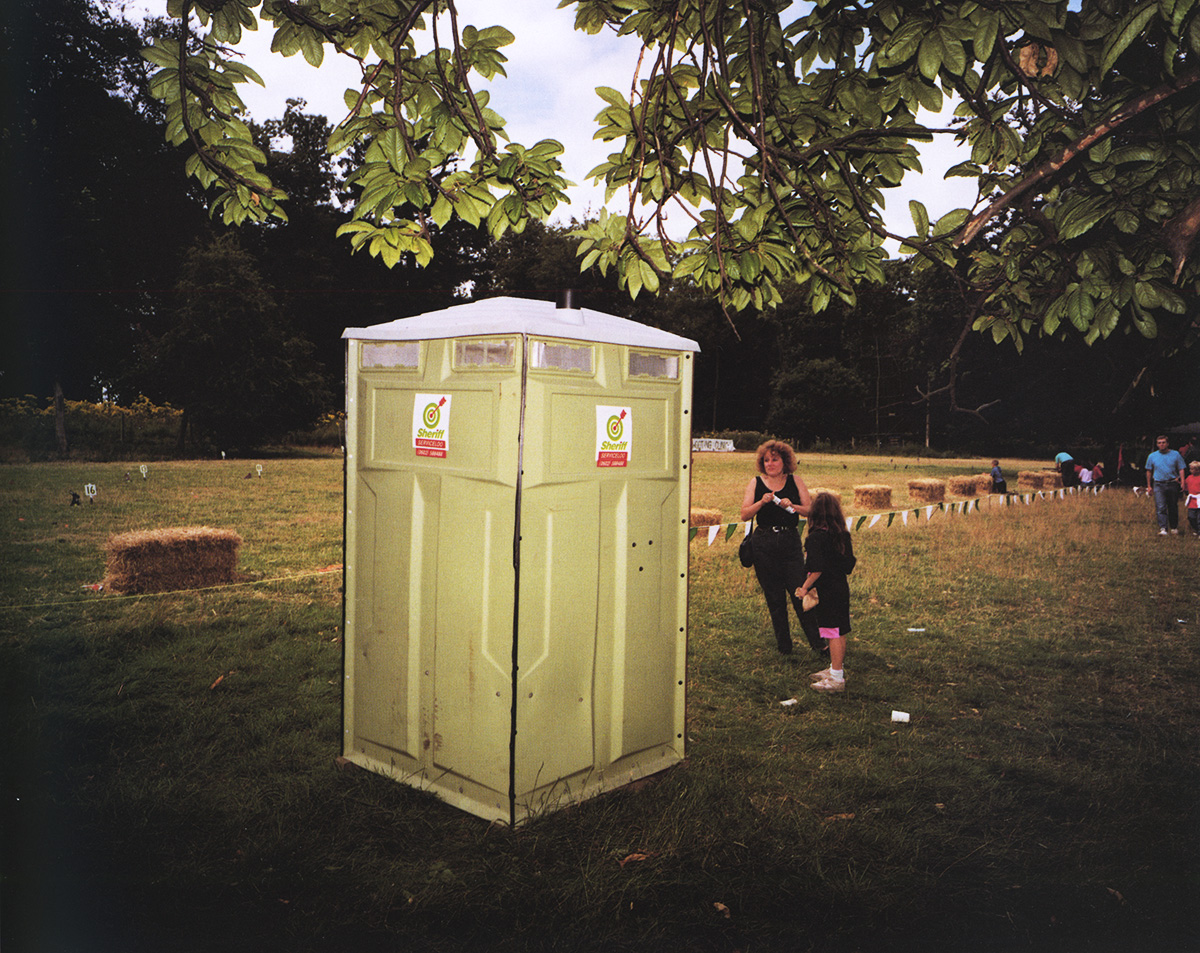

Patrick Sutherland is known for his environmental work, and did a lot of work in the late 1980s about farming. For CCPM, he photographed the contemporary countryside between 1991 and 1993, as it was undergoing social change. He was documenting the changes in this landscape traditionally known as the “Garden of England”. So he shot a golf driving range in Ashford, a clay-pigeon shoot in Chilham, and a mobile home in the landscape. Huw Davies crossed the Channel and showed how, since rural England had become occupied, France was the new frontier. Through a series of portraits and domestic details, he looked at the lifestyles and attitudes of a cross section of the British people moving and buying property there.

Karen Knorr, on the other hand, created work that was allegorical and symbolic, focusing on the common heritage between France and England, and the hopes for a better future.

Much of this photographic and social history was brought together in Soundings, a book that was published to commemorate the opening of the Tunnel in 1994. Over time, as organisational memory and archives are lost, the publication has played an important role in keeping the CCPM project alive. After the Channel Tunnel opened, the CCPM became Photoworks, but its mission has remained the same: to cross cultural and physical boundaries.

For more from #1 Europe, click here.