Text by Inès de Bordas.

Staged images of the lunar surface by 19th century amateur astronomer James Nasmyth, anaglyph stereoscopic prints invented by Louis Ducos du Hauron and the first images of the moon in colour and in 3D by Léon Gimpel are explored in an article by Inès de Bordas.

In the 19th century, progress in the field of optics and the development and availability of lenses and photographic processes resulted in new forms of perception, fulfilling an ardent desire to extend the field of vision to worlds invisible to the naked eye. Although microscopes and telescopes had previously enabled observation of specimens from the infinitely small to the immense and extra-terrestrial, the application of photography to the scientific field from the 1850s offered unprecedented possibilities for representation that not only significantly changed visual culture, but also substantially broadened our imaginative scope. It was suddenly possible to bring images of celestial bodies close to the public gaze, to project photographs of the moon onto large screens, or reproduce them in a book. ‘La Lune à un mètre!’ (the moon at one meter!) became the tag line used to announce the presentation of the ‘Grande Lunette’ (Big Lens), a monumental telescope at the Palace of Optics in the 1900 Paris Great Exhibition, and hundreds of thousands of copies of the illustrated 1880 book Astronomie populaire (published in English as Popular Astronomy in 1894) by French astronomer, polymath, and psychical researcher Camille Flammarion were sold to a wide audience in France and England.

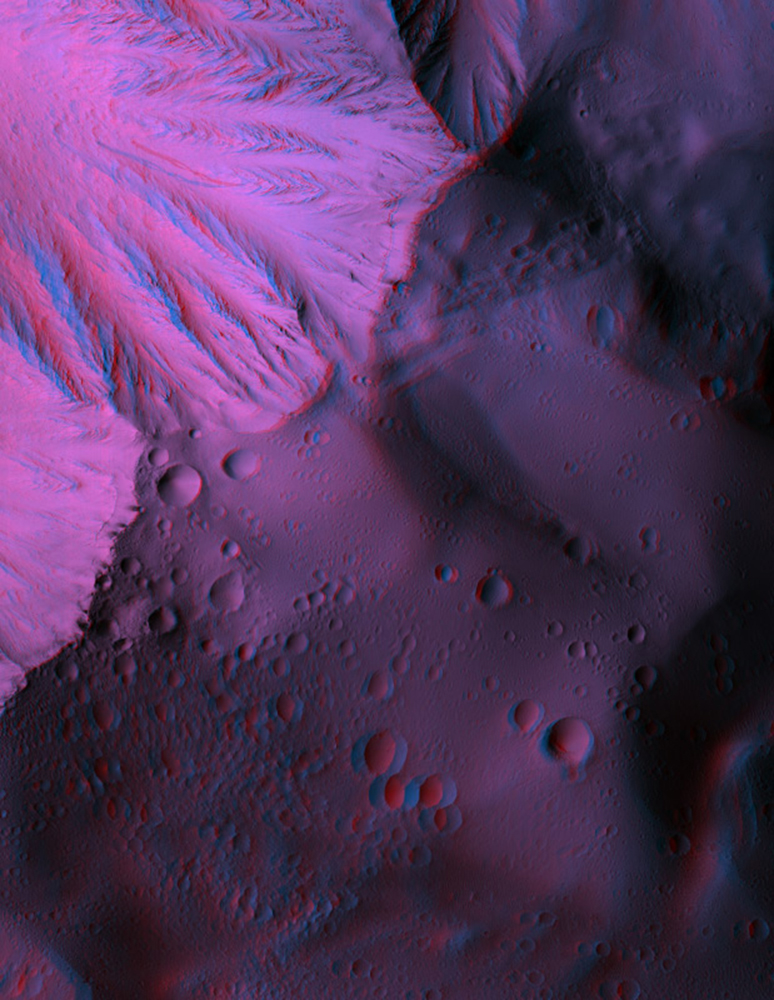

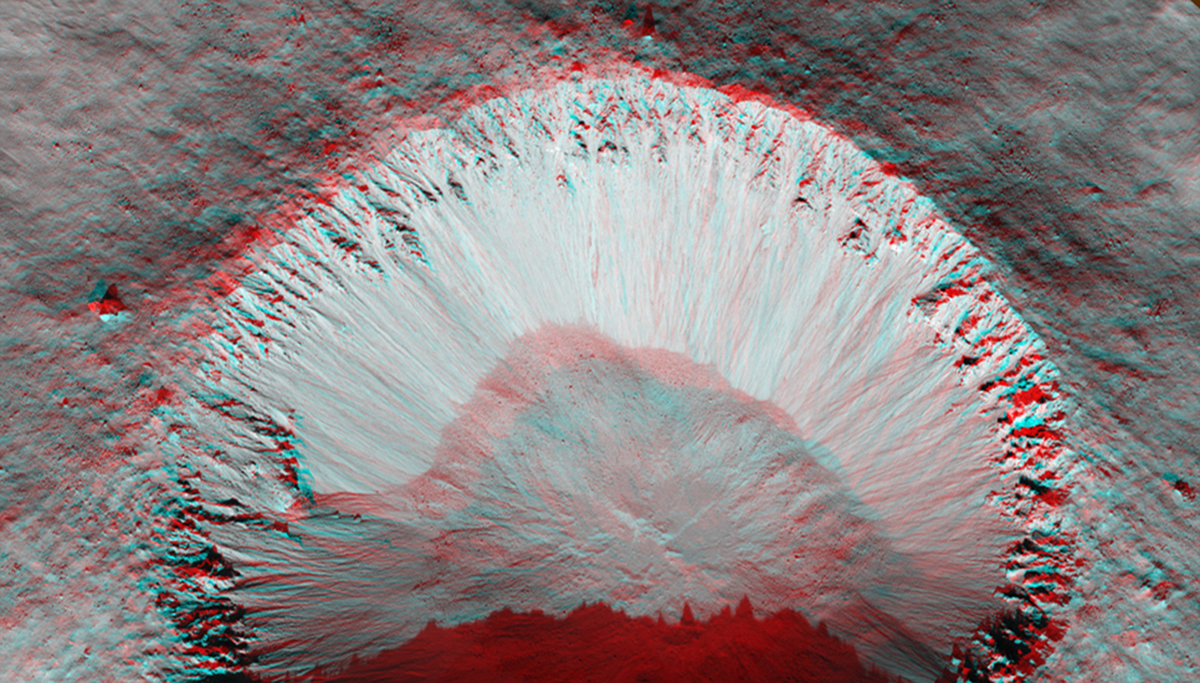

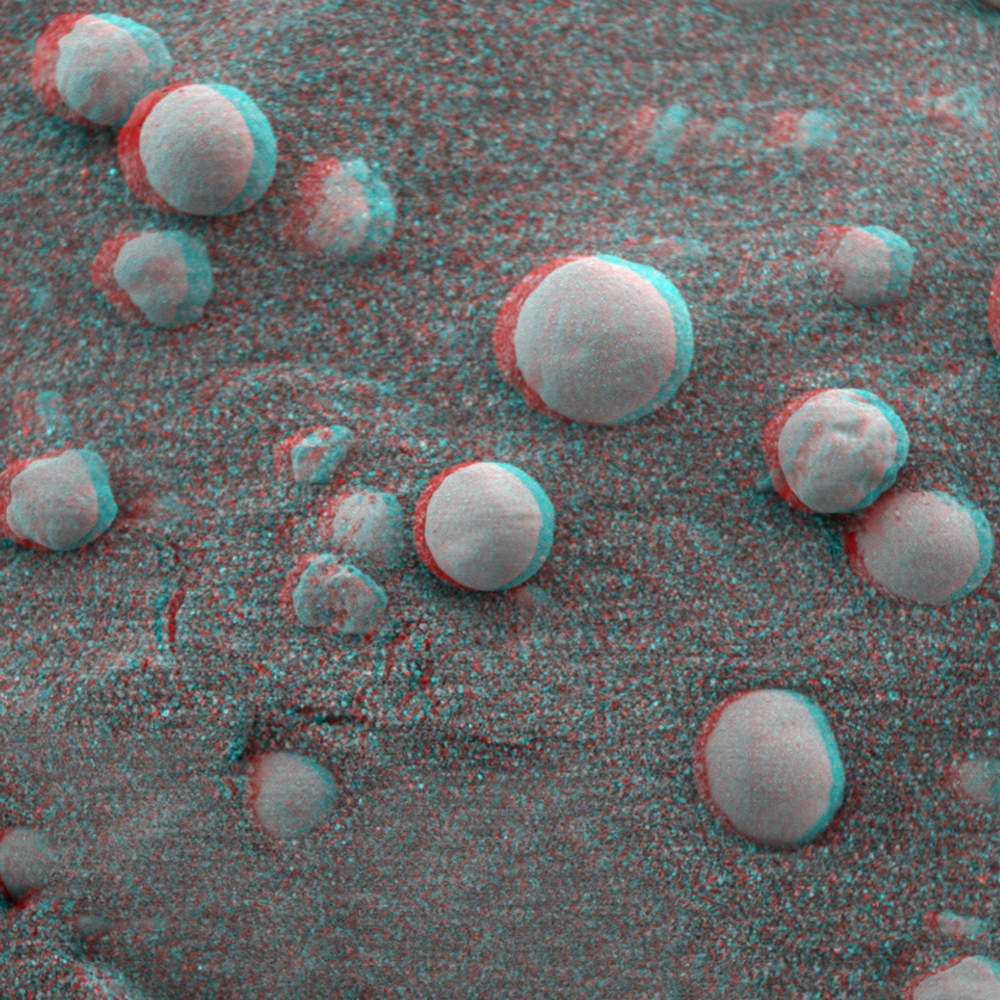

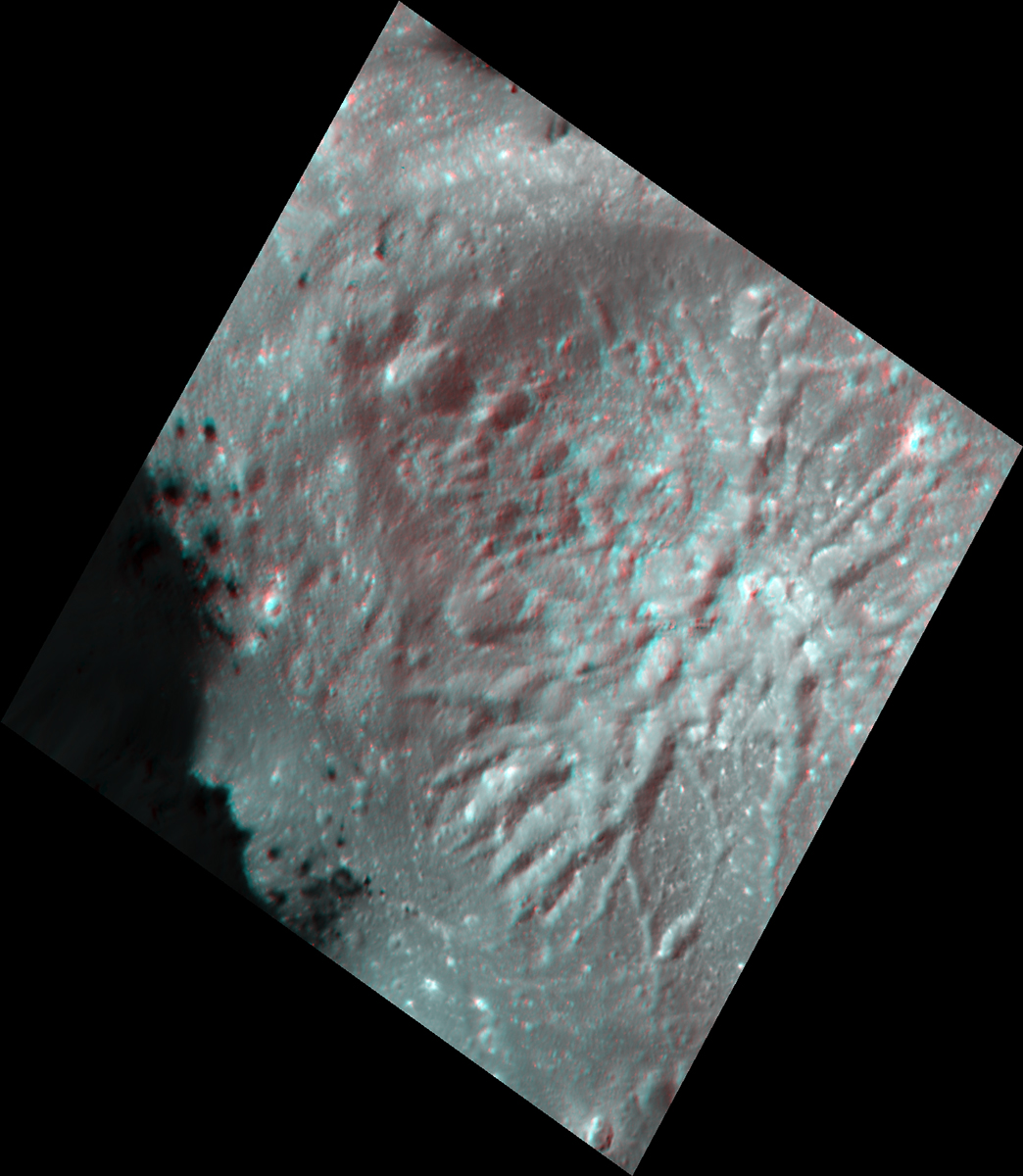

This quest to bring the moon closer to the human eye was not restricted to the production of 2D images. Scientists and photographers alike wanted to study the satellite, to show its relief, to render visible and accessible the topographic variety of the lunar surface. In his publication Les Terres du Ciel, Flammarion included photographs made by Scottish amateur astronomer James Nasmyth in the 1850s, and described them in terms of ballooning – another late 19th-century experimental passion: ‘Doesn’t it look,’ he says, ‘as though we are transported in a balloon only a few miles above the lunar surface, so that we can seize all of the details of this strange relief.’ Interestingly, Nasmyth’s images of the lunar surface were the result of an elaborate – and staged – process. At a time when lunar photography was still in its infancy and presented practical limitations, he made large-scale plaster models based on his meticulous observations and drawings of the moon as seen through his telescope. Each model was lit under controlled conditions and photographed in his makeshift studio in an attempt to convey the effects of light and shadow caused by the sun’s light striking the lunar relief. To this day, it is still extraordinary to think that an amateur astronomer like Nasmyth, working in his nightgown at the end of his garden at night, achieved such impressive verisimilitude. Side-by-side comparison of some of Nasmyth’s photographic translations of lunar craters or mountain peaks with images of similar features made recently by NASA shows how remarkably accurate he was in topographic terms.

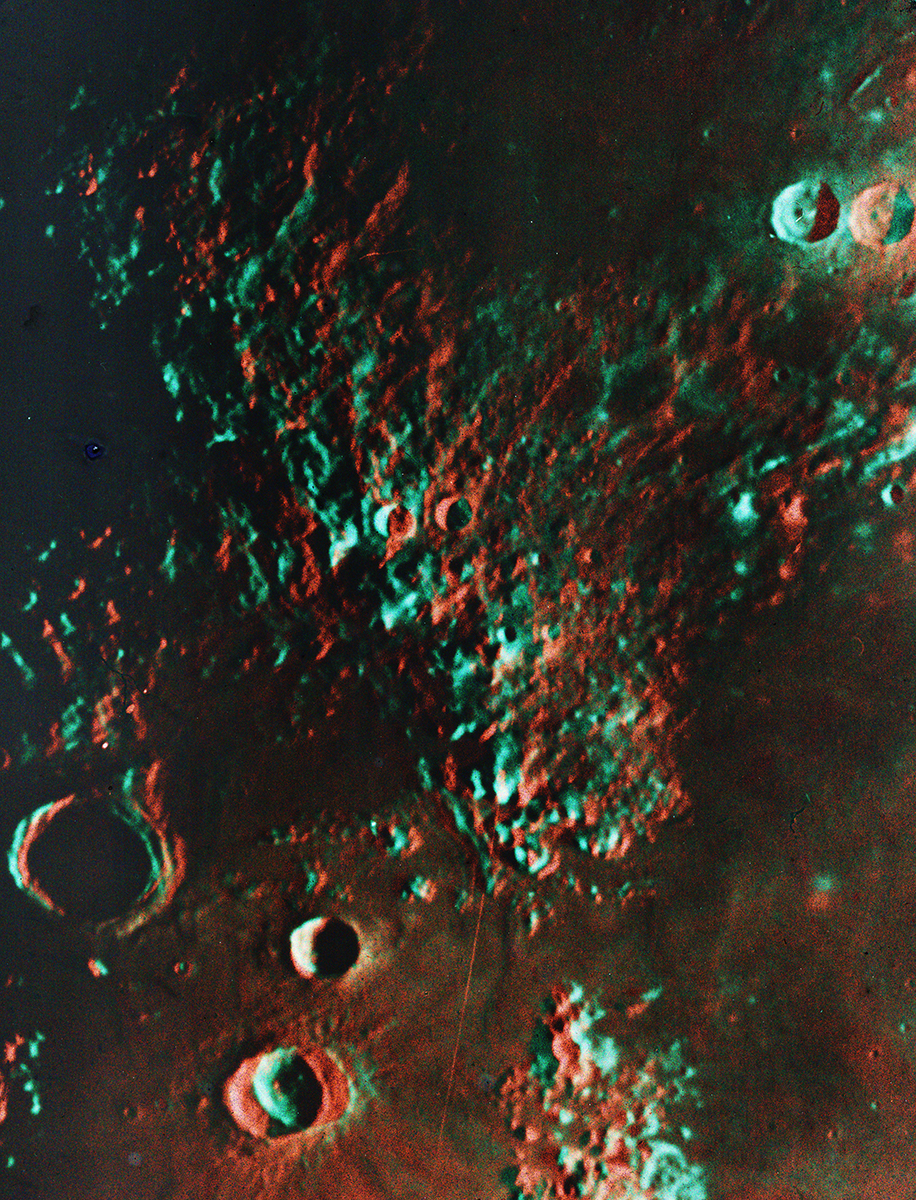

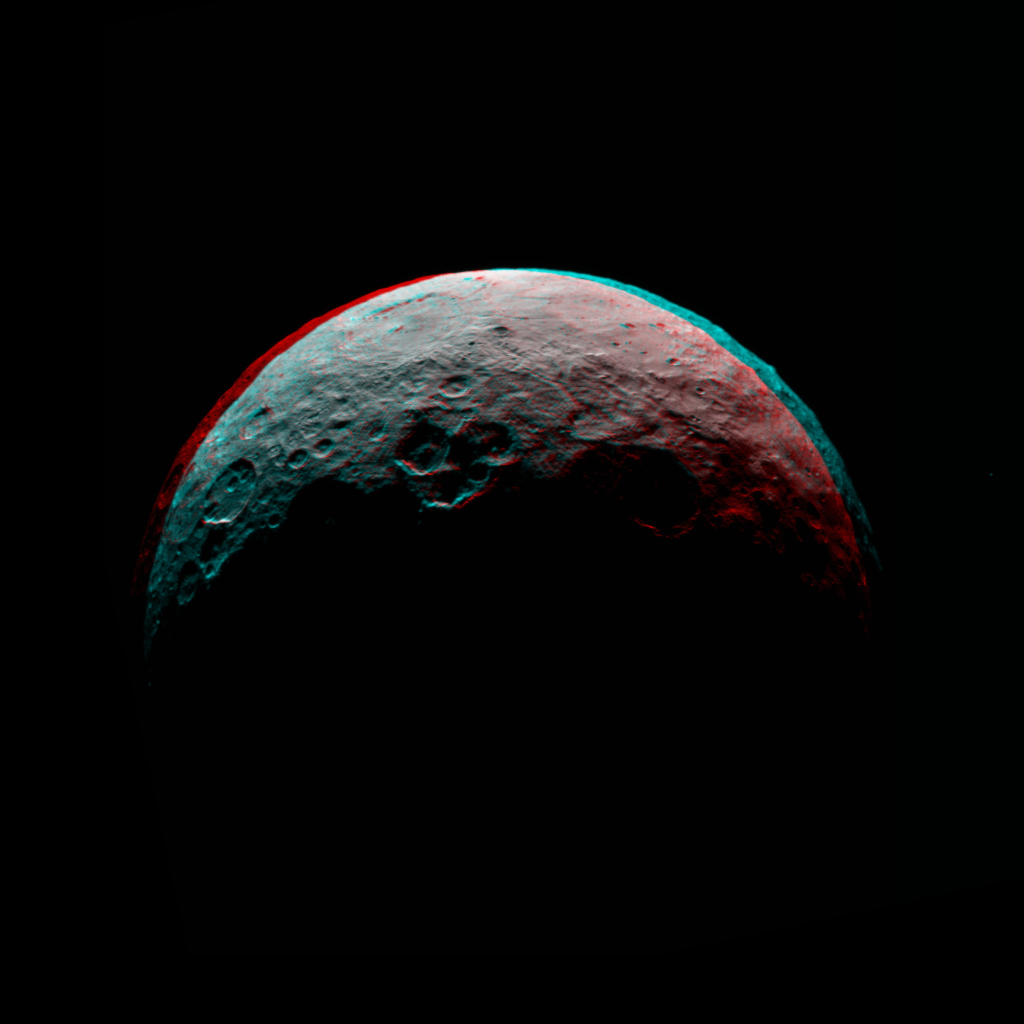

It was not until the end of the 19th century that the invention of the anaglyph offered the long-awaited possibility to reproduce 3D images. In 1891, a year after Nasmyth’s death, the French inventor and pioneer of colour photography Louis Ducos du Hauron developed and patented the process of the anaglyph stereoscopic print. The juxtaposition of a pair of images of an object taken from slightly different angles, as seen from the right eye and the left eye, reproduced one above the other, one in red and the other in green or cyan, and seen through glasses with one red filter and one green or cyan filter, is processed by the visual cortex as a 3D image. After the presentation of his 1893 paper the ‘Art of Anaglyphs’ to the Society for Sciences, Letters, and Arts of Agen in the south of France, Ducos du Hauron stated that he would give up the rights to his patent if anyone were ‘to print and publish an anaglyph image of the moon suspended in space’.

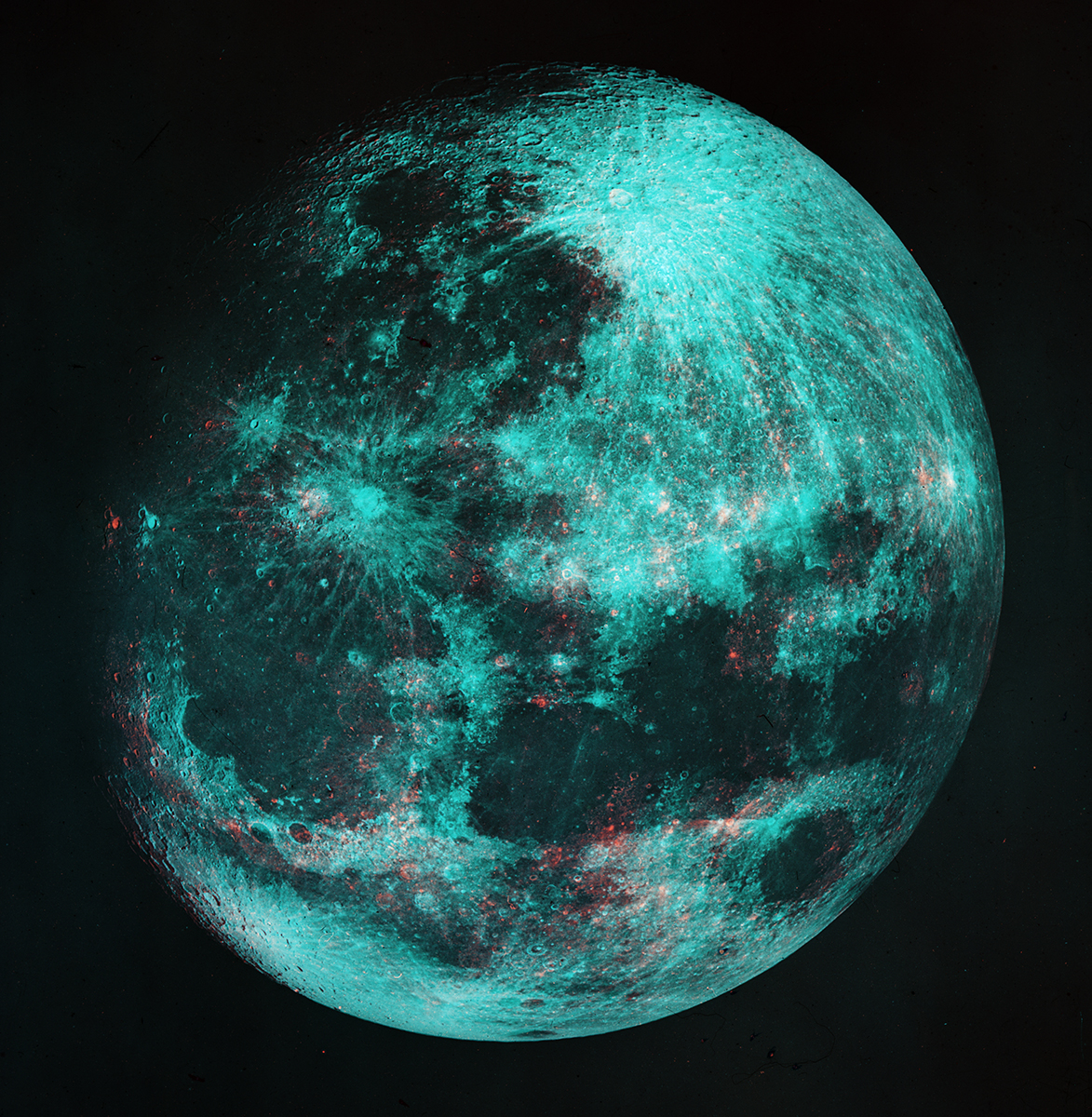

In January, 1924, the challenge was met when Léon Gimpel published two of his autochrome anaglyphs of the moon in the Parisian weekly L’Illustration and soon after in the Illustrated London News (both were sold with 3D viewing masks). In one of the images, a view of a full moon, Gimpel juxtaposed two photographs by Charles Le Morvan at the Paris Observatory, one taken in January, 1901, and the other in February, 1904 – this interval was necessary for proper alignment of the moon and for the moon to be ‘as it would appear to a giant with eyes 28,125 miles apart, and observed by him from a distance of 240,000 miles’. To obtain the views of the lunar mountains in the other anaglyph, Gimpel also resorted to the process of hyperstereoscopy, whereby the distance between the two viewpoints exceeds the distance between the viewer’s eyes to increase the sense of depth. In an extraordinary collapse of notions of time, space, and scale, Gimpel’s lunar visions, the first images of the moon in colour and in 3D, were shown on the pages of L’Illustration as part of a larger group of anaglyphs that included subjects as varied as a housefly, a wrist watch, a portrait of Camille Flammarion, snowy mountain reliefs, clouds, and an Egyptian pyramid.

Oscillating between scientific observation and magical spectacle, Nasmyth and Gimpel’s images of the moon remind us that, from the outset, the application of photography in astronomy fused science and fiction in an attempt to best render the lunar surface, despite the distance that separates it from earth. Today, NASA still uses technology based on 19th-century anaglyphic processes to study the topography of celestial bodies, and the sense of wonder evoked by looking at far-remote planets through 3D glasses remains intact.

____

Léon Gimpel’s anaglyphs are currently part of two exhibitions: Man/Moon at the Foto Museum, Antwerp (loan by Archive of Modern Conflict) 28.06.19 – 06.10.19, and The Dark Side of the Moon, a 50-meter mural bringing archival material ranging from 1895 to the 1970s curated by the Archive of Modern Conflict in collaboration with French artist Sebastien Girard for El Centro de la Imagen, Mexico City 26.07.19 – 06.10.19.

For more from #3 Space, click here.