American artist, writer and publisher Gregory Eddi Jones, discusses his ongoing practice and image making process. His work interrogates politics of common cultural images through strategies of appropriation and re-authorship and is part of #7 Anniversary.

Could you explain your practice and how you work in a few sentences?

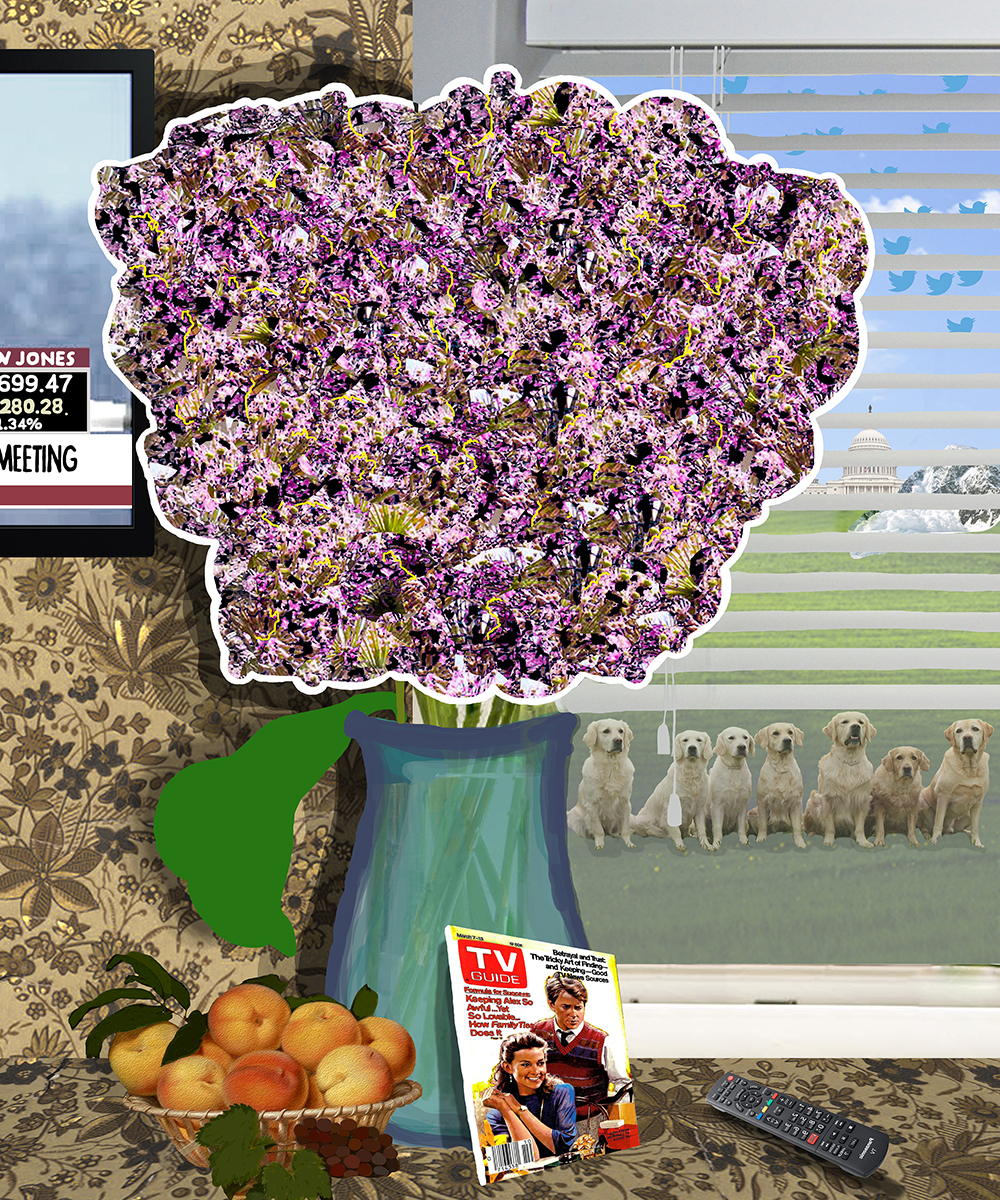

I appropriate images and re-author them with various collage and manipulation strategies. The way I work is spurred by feelings about how photographs act upon us, the state of the world, and the whims of my mood on any given day. It’s difficult to rationalise how powerful an influence a picture can have on us. A photograph is a one-way channel of communication: you can’t argue against it, and you can’t un-see it once you have seen it. It conveys an idea that is fixed in visual space, and arguing against the rhetoric of an image is like blowing air at a rock – no matter what is said or written, the pictures don’t change. They stubbornly persist as long as there are eyes looking at them.

I’m interested in having conversations with pictures, in questioning them and critiquing them. And the only place for that conversation to legitimately occur is within the visual space. So, I change a picture to change its argument. More often than not, I work with very common and familiar types of pictures, which perhaps are the ones we need to be most sceptical about.

What one thing has most helped to shape your practice?

Jeez, I don’t know. If I had to narrow it down, I think it would be my ethos of generally disagreeing with everything as much as I can muster. The only way to envision something new is to consider how things can be different. Van Gogh would never have done the work he did if he agreed with what the world looked like and abided by that in his pictures. Finding a creative path, one that is uniquely yours, requires that you disagree with everything until you find something you can’t possibly disagree with.

Why photography? Why the still image?

I’m by no means a photographer in a common sense. I haven’t used a camera in a creative way in years. The things I want to make pictures of or about aren’t visible in the physical world. But I’ve found photographs to be marvellous points of departure for deeper investigations. They have such unresolvable relationships to truth, belief and lived experience. Photographic tools are pre-loaded with a vast set of conditions and problems to solve, as if meanings are already imbedded in the media, and it’s up to the photographer to recognise them and to give them shape. I’m continually surprised by what photography can do, and I believe that it still has secrets waiting to be uncovered. Photography is complicated, and it seems like a fitting medium to use to describe our world. But photography also has its burdens, and I abandoned the camera because it became an inadequate tool to make the kinds of pictures I wanted to make.

On the still image, I am enamoured of the idea of a rectangle as a field of endless possibility for invention. I’ve been thinking lately about the rectangle in terms of a sports field, a set of boundaries within which any game can be played. Artists can play old games with traditional rules, they can make up new rules to old games – or they can invent their own games and make up their own rules, which is what I try to do. It is immensely difficult but incredibly fun. There are lots of mistakes and odd outcomes, as well as surprising results.

Where do your ideas begin?

I’m not sure. I think they mostly begin after I make a new picture and try to learn why I made it, what influenced it, what it says to me, and what larger conversations it wants to participate in. If I find answers to those questions, they start to guide how I make the next picture.

I used to approach work with a concept in mind, make a picture to try to realise that idea, and then get lost in the discrepancy between what I meant to do and what I actually did. I don’t want to fall into a trap of making pictures that are pre-rationalised too much. I want to make pictures that exist beyond the threshold of my rational understanding. It’s a less disciplined way of picture-making, but allowing feeling and intuition to guide my making is far more rewarding, less stifling, and ultimately more honest.

What’s next?

Over the past few years, I’ve been obsessed with T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. It’s a modernist poem, written in an entirely collage-like fashion, that reflects on the loss of social and moral clarity in the UK after World War 1. I’ve found a kinship between the social conditions Eliot described and what I feel like I’m living through in the USA now.

It’s a very difficult poem to read, but an enormously rewarding one – probably one of the most creatively ambitious pieces of art I’ve ever encountered. Every line of it feels charged with meaning and knowledge. I’m now making pictures that borrow from the literary strategies Eliot used in The Waste Land, and am working towards publishing a book that works as a sort of contemporary American visual update to it. The one hundredth anniversary of the poem’s publication is in 2022, so it feels like the right thing to do. Hopefully I’ll find a good publisher for it.

Read more Photography+ Learn more about this artist