From issue: #19 Image Flow

Saman archive started as a collection of negatives taken by professional photographers in Ghana but, says founder Adjoa Armah, the project is much more than a picture library. Taking in many other aspects of Ghanaian culture, it also encompasses her diasporic relationship with the country, and how we think of and create archives. Photography+ writer in residence Sabrina Citra finds out more.

2015 marked Adjoa Armah’s return to Ghana, sparking a journey to build a relationship with the country of her birth beyond the abstraction afforded by the distance of diaspora. Armah, who was brought up in London, explains: ‘Ghana is my home to the extent that it is my country of birth. But really internalising it as my home is a feeling I have had to seek out and continue to search for, even though over the past seven years I have spent almost as much time here as I have in the UK.’

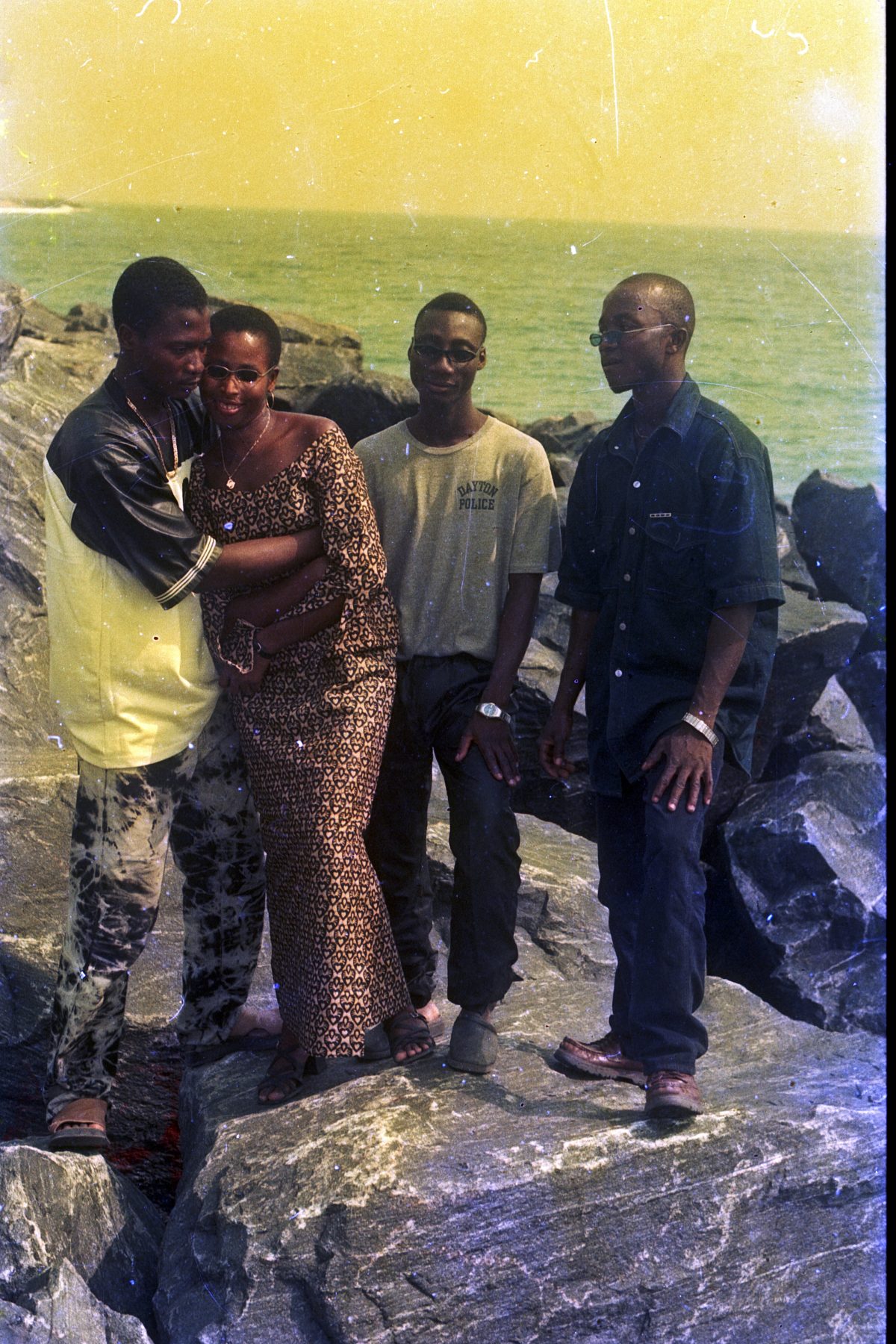

Photography became Armah’s means to navigate place, her film camera becoming her companion in travel and opening up new ways of seeing. She was interested in documenting Ghanaian street life, photographing sellers, particularly enamoured by women carrying goods on their heads until, upon reflection, she realised her discomfort with the gaze that persisted in her early photographic practices. She felt that her photographs delivered an over-stylised portrayal of Ghanaian life, perpetuating a fantasy of home enraptured with what she refers to as a ‘diasporan aesthetics’.

‘I have a lot of critiques of certain diasporan relations with home because I think they can conveniently sidestep self-reflection, and truly acknowledging power and privilege is difficult,’ she says in our phone call. ‘Proximity to Europe or North America significantly shapes how you’re able to engage with home.’

Armah is deeply aware of her position within the Black diaspora, recognising that their relations are shaped by a spiritual desire for return. The complexities of defining home, alongside the question of return, have informed her archival practices, her work with what she’s named saman archive. ‘The way I relate to saman archive and think about how to work with the archive is folding this question of return, what it means on a personal level for me and what it has meant more broadly for others in a similar position to me, by building a relationship with the country and all its complexities,’ she says.

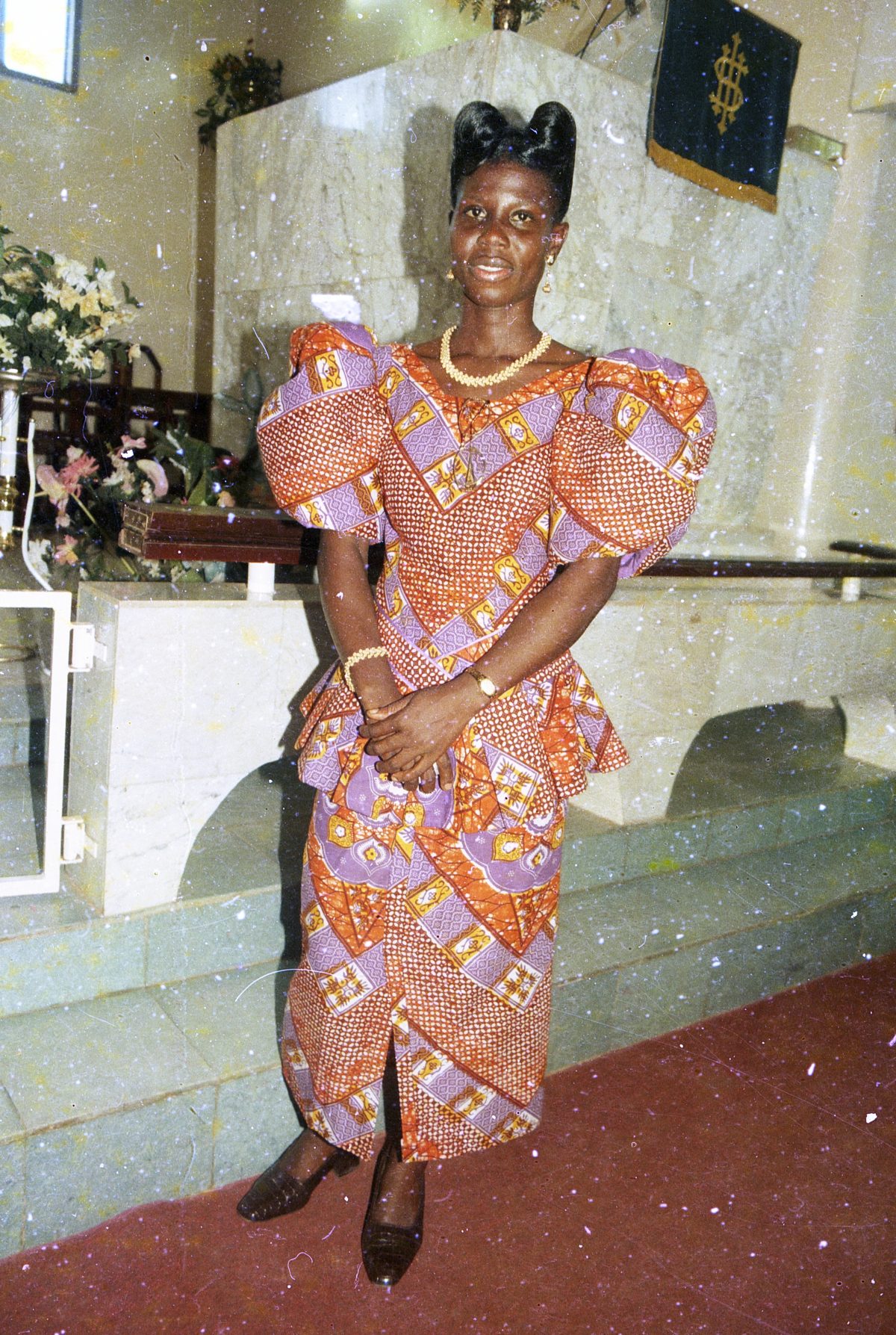

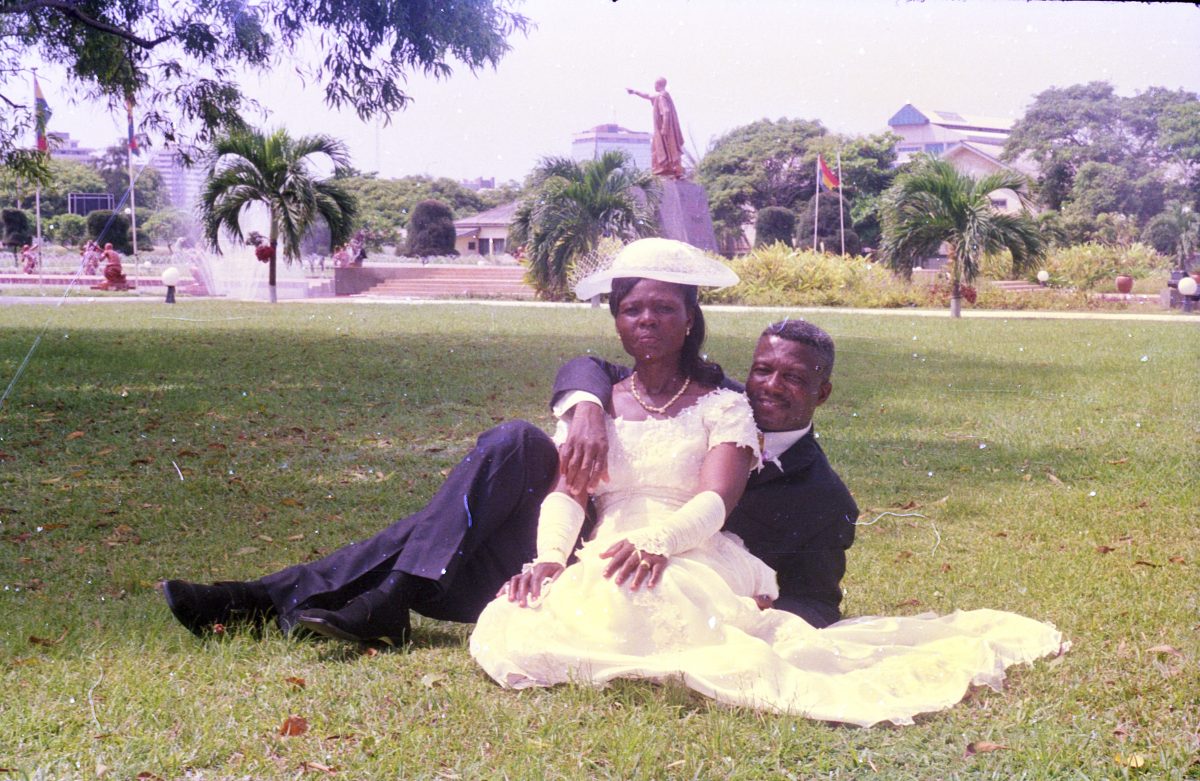

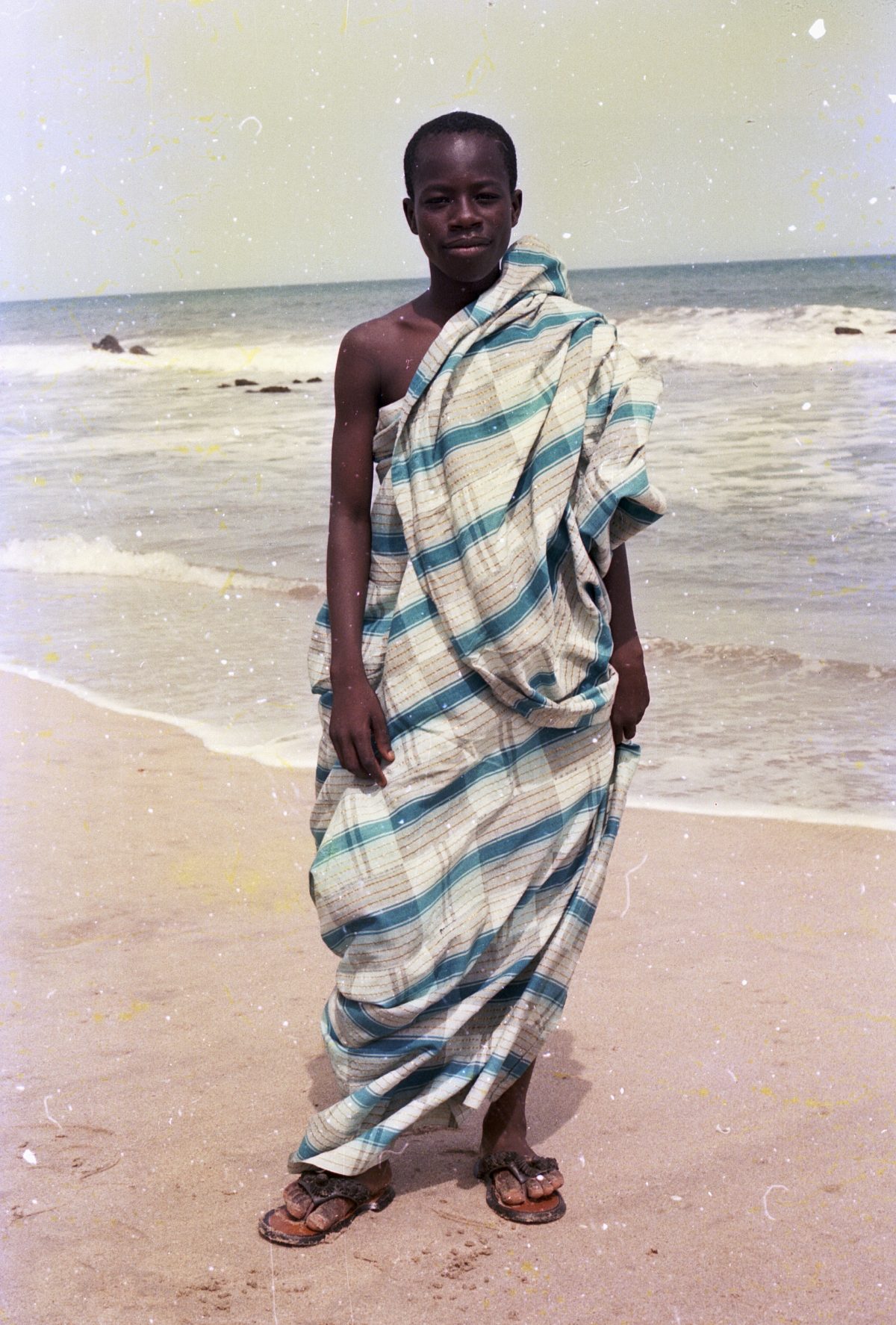

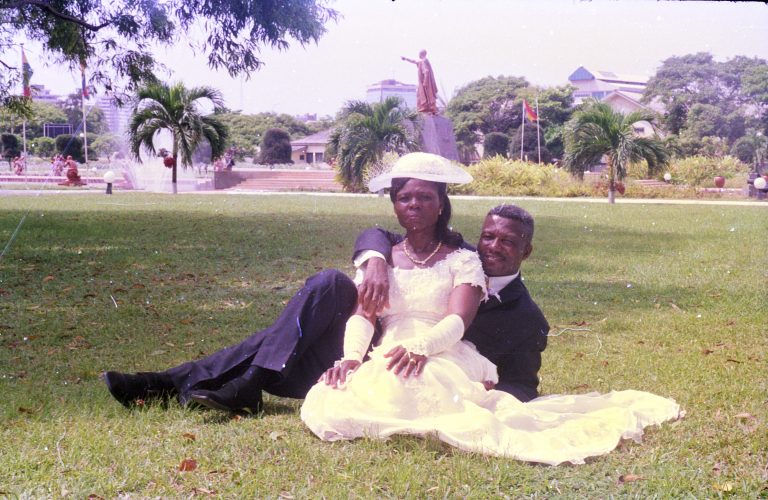

In this sense the archive – not just saman but how Armah approaches collection, research, and navigating visual and material culture – has become a site that articulates Armah’s relation to Ghana, guided by the people, places and ideas she encounters while developing it. Its contents stand as testimonies to her experience, which began from her collection of photographic negatives – mostly portraits shot by Ghanaian studio and itinerant photographers, many of whom often destroy their negatives after several years, once it’s unlikely that their customers will return for reprints.

For Armah, collecting these images is a gesture towards an approach to history that recognises her own preoccupation for insight into the life that “could have been”, had she been raised in Ghana, which fold into broader questions of how we can know a nation beyond the hegemonic narratives told about it. Armah seeks to move beyond ‘objective’ historical narratives, acknowledging how her own desire to rearticulate her relationship with home is foundational to saman archive’s formation.

This desire is not unique, she points out, but is in fact very common in the way many people of the Black diaspora engage with the nation, as the first African nation to gain independence and a point of departure for many in the Americas and the Caribbean. For Armah, if the relationship so many have with the nation relates to the Trans-Atlantic trade, it is imperative that her approach to archive building, and narrating its past and present, rejects the logics that could justify the violence of this trade.

‘I need to constantly be looking at what I want from the archive and of my practice, to try to make sure that I’m not reproducing the world as these systems that gave rise for the need for return for so many take as common sense,’ Armah explains.

Armah has named the archive after an Akan word for ‘ghost’, which can be used colloquially in Ghana to refer to photographic negatives, but also resonates in other ways. ‘I think everything starts with “saman”, not even the content of the archive, the negatives, but “saman” as a term,’ she says. ‘I’m interested in what it means to have an archival practice that is guided by or responsive to people who aren’t here anymore. For me, the ghost is a figure that helps me think about what we owe to the past, because it’s like a figure that demands “This happened and I am owed repair”.

Saman archive expanded to recognise the ghostly within the act of archiving, for example, as Armah found herself inhabiting spaces populated by ghosts, particularly within the European-built forts along the coast, and Colonial and State archives. While navigating these sites, Armah thought alongside scholars such as Katherine Mckrittick and Saidiya Hartman, who recognise the violence imbued within these archives. Referencing Cameroonian historian Achille Mbembe’s concept ‘chronophagy’ [‘time-eating’], which describes the state’s desire to anaesthetise its past, Armah posits the artistic practice that has developed out of her archival work as a means to create historical narratives that reject the capacity for the archive as a site that is able to consume time in order to be free from its debts.

A student of Black geography, Armah aims to create a place for liberation in the physical and the imaginary, to work towards a more liveable future for Black people. Saman archive recognises the limitations of using descriptive narratives in historicising; the language that guides Armah’s histories is intended for a communal healing. ‘How do we describe history with the acknowledgement that description itself is not something that is an act towards repair?’ she asks. ‘And if I acknowledge that, how do I find ways towards these various disciplines that might start getting to the place that I’m trying to get to, acknowledging this as constant journeying?’

This questioning has encouraged Armah to make saman archive public, which started via Instagram and expanded via residencies such as at London’s Gasworks in 2021. She’s been guided by the photographers in this process, only showing images with their consent, and asking if they would prefer to be credited or remain anonymous. Upon curation of the negatives, Armah has been conscious of the sitters’ consent – or lack of thereof – and as a result feels responsible for safeguarding their privacy. This has affected the location of archival materials, returning them to Ghana rather than keeping them in London, as she originally did.

In the early days of saman archive’s Instagram, Armah displayed the negatives she had collected through Instagram stories, presenting each narrative as a collage that hybridised the negatives (she basically reconfigured them to highlight the textures) with iPhone footage of her travels through Ghana. More recently she has delved into contemporary art as a site to expand saman archive, allowing her to explore questions limited by the photographic form. In 2022, she had an exhibition with Auto Italia Gallery, London, for example, which merged text, sound and performance to enliven the places in Ghana important for her research.

It displayed 3D sketches of linguistic, historical or social mediation instruments that were flocked in sand gathered from the Ghanaian coast. Combined with Armah’s field recordings from her travels, the exhibition explicated her interests in mixing materialities of text, sound, and performance to create a performance dramatisation. Titled the sea, it slopes like a mountain, the exhibition was a homage to the oral cultures that have shaped relations across the Black diaspora.

‘[It’s] thinking of how do we, as Black people, know each other better from Ghana?’ she explains. ‘Thinking about Ghana’s relationship to the history of the Black Atlantic and understanding the beach as the footnote to the Atlantic Ocean.’ This constitutes the unfinished research from a wider project Armah is working on, titled in our language the word for sea means “the spirit that returns”, which focuses on the sea as a repository for histories intimate to them.

And these relations have been guiding Armah both now and for the future; when I ask about the future for saman archive, she says she has a 200-year plan for it to be built into a physical site, which will invite people in. Armah doesn’t want saman to be dependent on her presence; she envisions it becoming a public site. ‘This is a lifetime’s work,’ she says. ‘I’m nowhere near getting to the point that I’m trying to get to. But you can do the work, you can do the slow work, you can build the relationship, and you can make that commitment.’