From issue: #18 Science Fiction

written by Sabrina Citra

‘It actually started because I was really, really angry looking at this constructed wall,’ says Anshika Varma. ‘I began asking myself “Why am I feeling so foul? Why am I feeling so restricted and constrained?” And that brought me to understanding and realising that I had lost my time and my relationship [with the forest] by just being a passive viewer.’

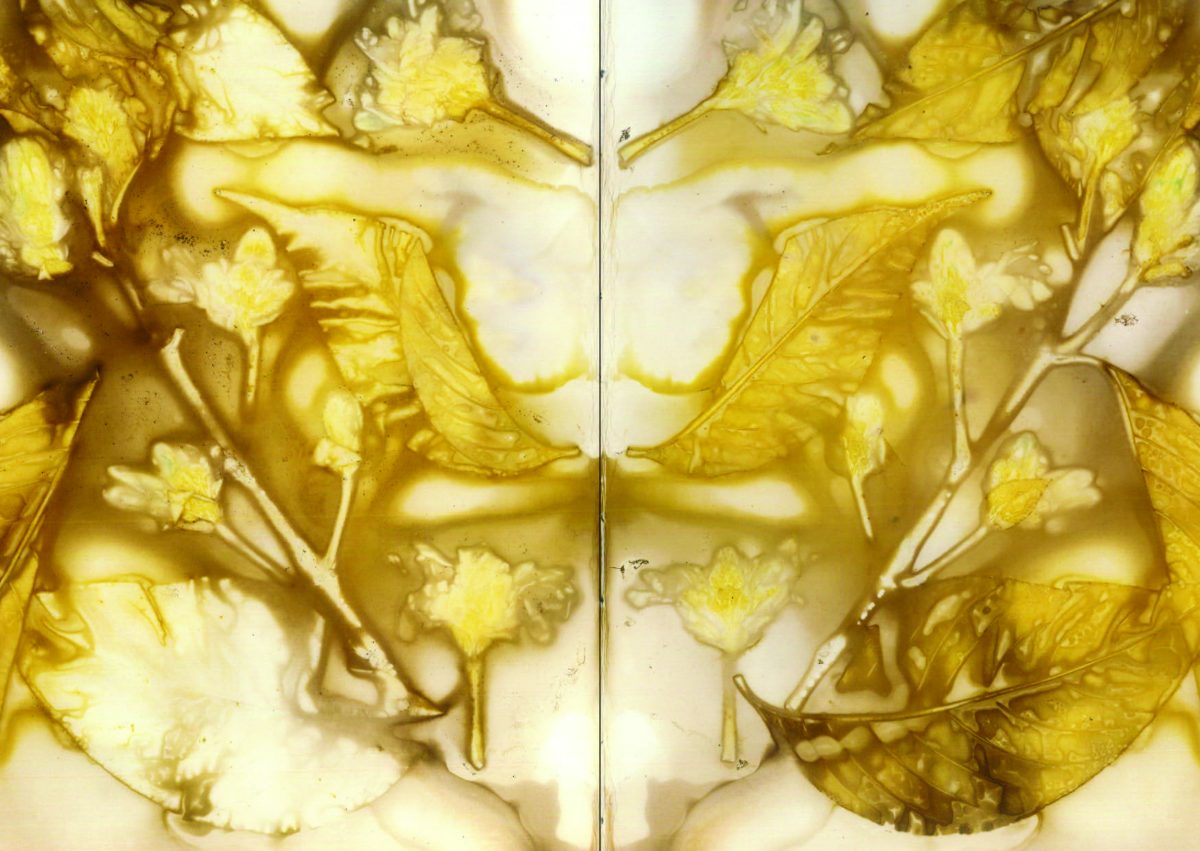

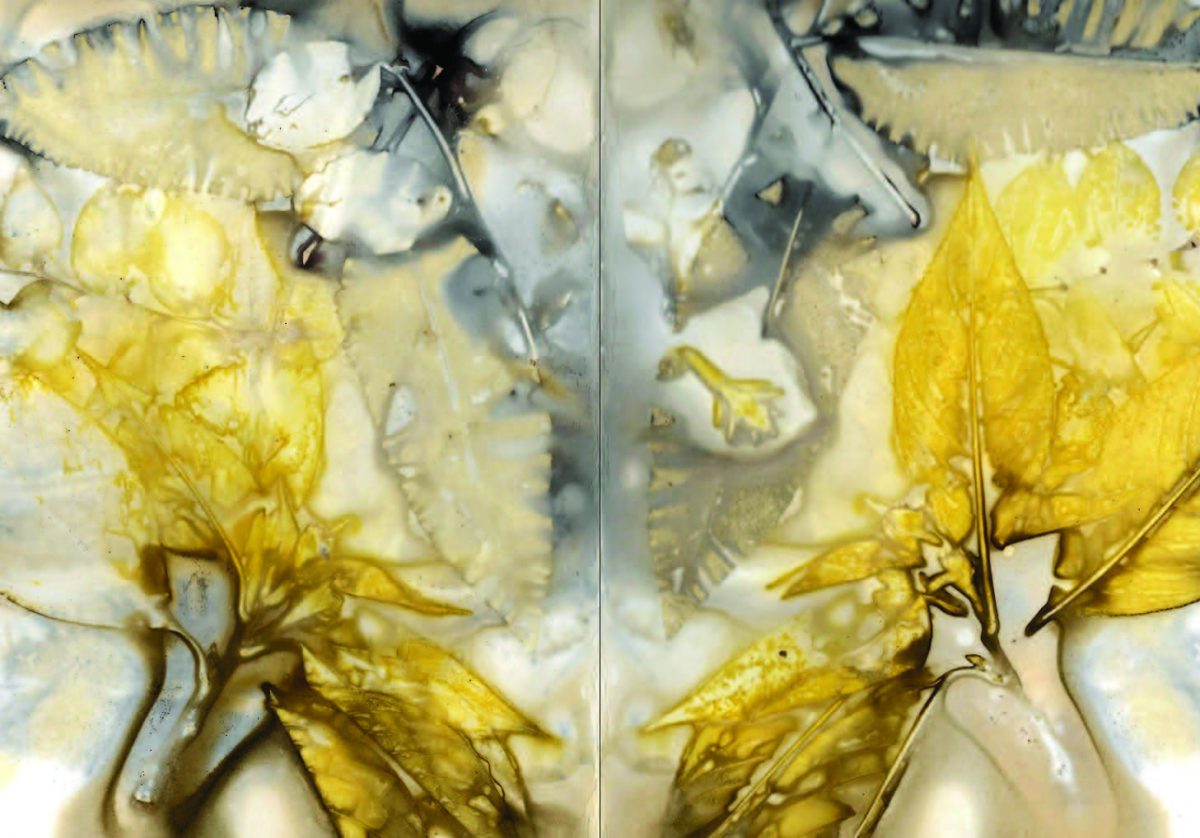

We’re discussing The Wall, Varma’s work on the Sanjay Van Ride Reserve in New Delhi, which is included in the Photoworks Festival 2022. The reserve is a forest which was once a sanctuary for the artist, but is now surrounded by a physical barrier, and policed and guarded by the state. The series is a testimony to reclaiming memory, and Varma began it by photographing the native trees, the Ronjh, Hingot, Bistendu, Juliflora, and Jal, plus what was left of the local flora, such as Bamboo, Dhak and Neem, as well as fragments of the wall. Accompanying these images are collages of foliage, which pay homage to Varma’s childhood hobby of collecting leaves and flowers, and pasting them into her notebook.

The project also includes a text depicting a child wandering through the forest which, on first read, I took to be Varma herself, inviting her audience to see the woods as she once did – partly as a real place, and partly as a fantasy world. She beams with joy when I mention this. ‘I’m so happy to hear that!’ she says. ‘I mean this [series] is for kids, that’s what you do in the forest, you just sit and fantasize. I wanted it to be that….I wanted to feel the world that exists in the forest as what you, as a child, have made it to be.’

For Varma, this conception of nature is key. She believes we need to establish closer ties with the environment right from childhood, a relationship in which we understand the natural world as an entity worthy of love not a commodity ripe for exploitation. For her, if we begin from love then care will naturally follow, and that will allow for an ‘organic’ preservation. ‘Why can’t we focus our energies towards falling in love with nature?’ she asks. ‘We don’t have to fight this battle anymore then.

‘You don’t have to tell people that they need trees to breathe because yes, we all know that,’ she adds. ‘You’ve given us statistics about it, we’ve converted the dynamic and that relationship into figures and numbers, we have all the data for that. But how do we explain how nature feeds us as human beings?’

It’s a conception she played with in her first presentation of The Wall, exhibited in 2017 at the Angkor Photo Festival. Attempting to recreate the forest in the gallery space, it was a multi-sensory installation for which Varma wetted rocks to mimic its scent, played recordings to evoke its sounds, and created tiny terrariums to showcase its vegetation. Then in 2020, in search of a more intimate interaction, she made the series into a book. ‘The book was very central because it offers different worlds to you as a reader,’ she notes. ‘You can make it exclusive to your own experience.’

Making a book also proposed a different conception of the forest because, as Varma points out, storybooks and children’s fairy tales from the European canon have shaped a particular expectation of woods around the globe. Valorising a particular kind of foliage only found in the Northern hemisphere, these narratives have created a particular perception of how forests should be. ‘There weren’t any storybooks that have allowed for a love for rocky forests to exist, or a barren forest to exist, or a lush forest in central India that dries up and becomes yellow once in the summer,’ she points out.

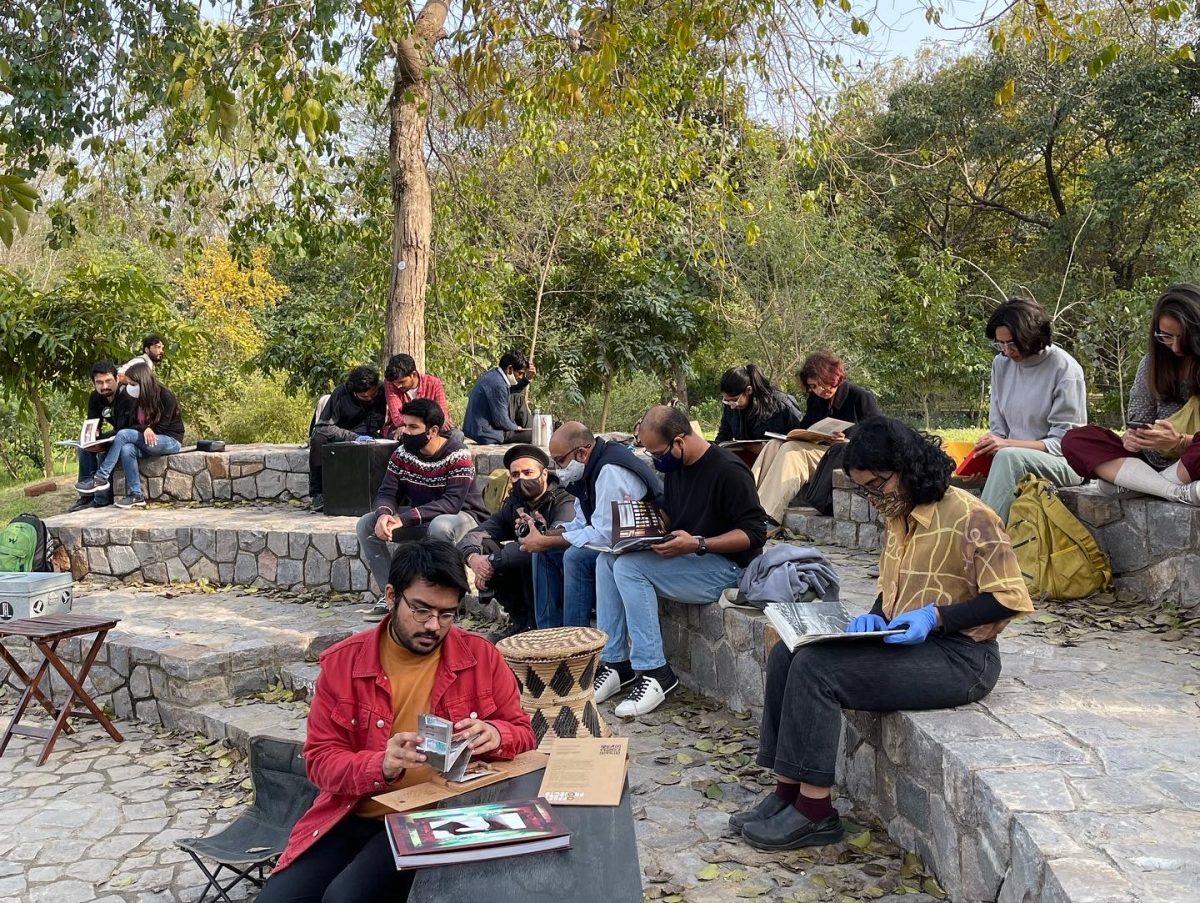

In this sense her book questioned the gaze pre-defined and dominated by European and American ideals, becoming a medium through which to ask, ‘What is the aesthetic of a postcolonial visual idea of beauty?’ And that question has influenced some of Varma’s other projects. Her Offset Projects initiative facilitates photobook publishing, artists’ talks, workshops, residencies, a library, and pop-up reading rooms, for example, aiming to facilitate meaningful engagement and reflective enquiry into photography and book making. It also encompasses the Offset Bookshop, India’s only photobook store focused on independent and self-published books from South Asia.

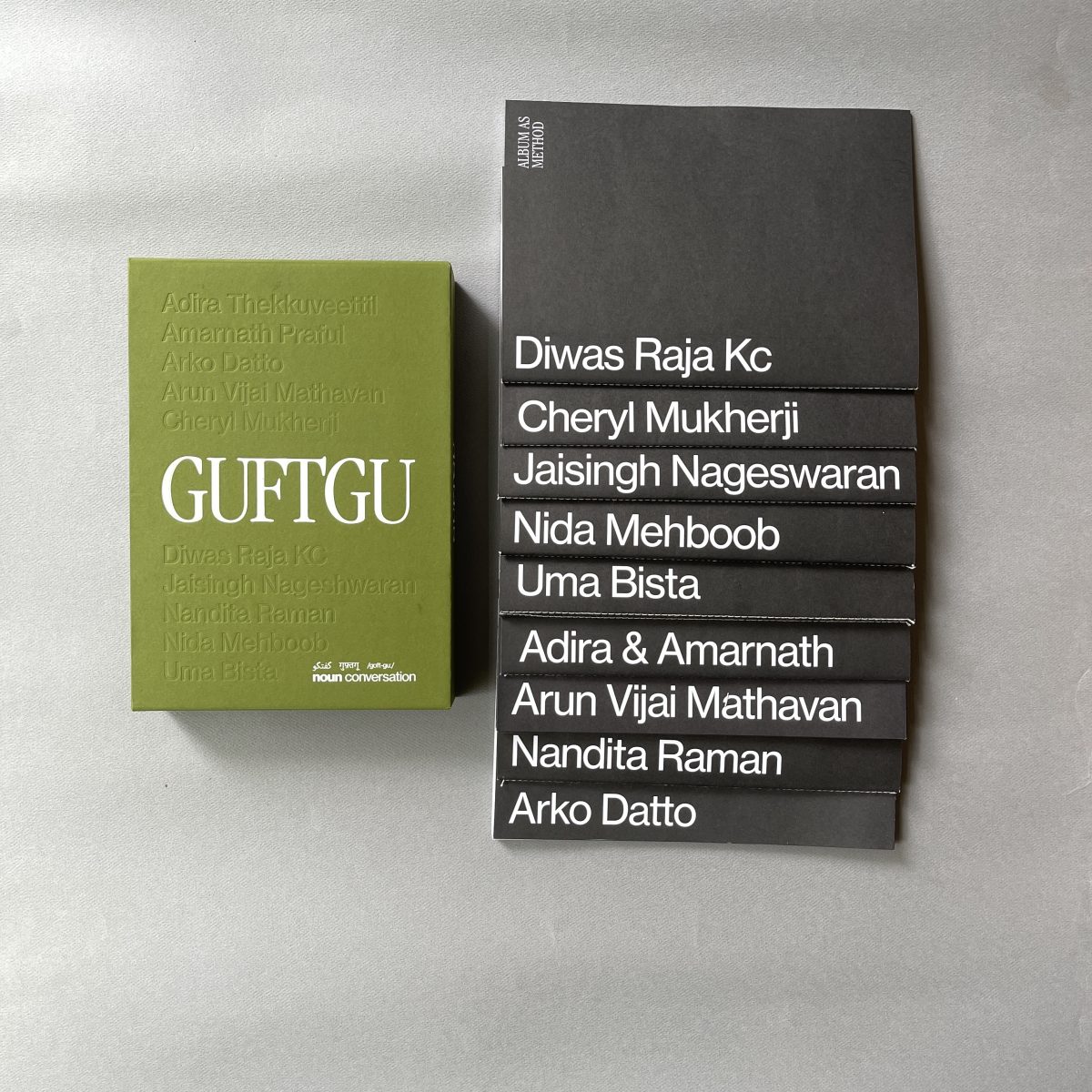

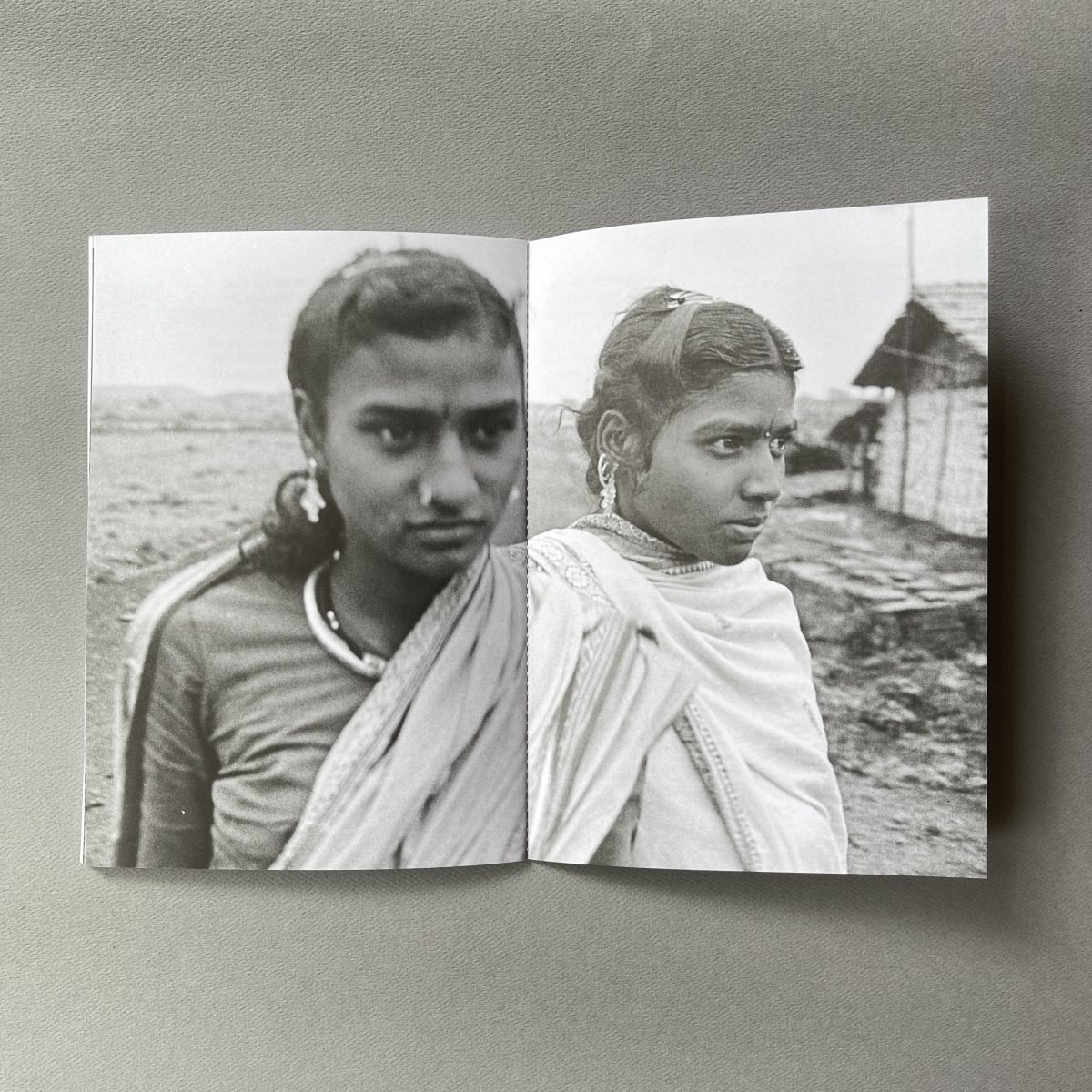

This year Offset Press published Guftgu, a deconstructed photobook featuring chapters by ten different artists from India, Nepal, and Pakistan, and edited by Varma. This publication rejected a singular expression of South Asian-ness, its title translating as ‘conversation’ and its process rooted in collaboration. And Guftgu became more than an idea, adds Varma, evolving into a practice in connection through photography, articulating the diversity of the South Asian region through an intersectional approach to gender, class, caste, and identity.

‘I consider these relationships as sacred,’ she explains. ‘That’s why I’m working with people around me towards creating something together, because I find that special.’