Arwed Messmer: Aktion and performance

Text by Nicola Jeffs

1967’s Summer of Love was a time of peace, love, and a new type of post-war youth culture characterized by hedonism, narcissism, pacifism, and reformism. By 1968, this short-lived era of sunny idealism had been replaced by the Days of Rage. Spurred on by American involvement in the Vietnam War and escalating calls for revolution, protestors took to the streets across the Western hemisphere, with state reaction swift and often violent. These turbulent times are well documented in photography: images of angry youths on the streets of the world’s capitals, fists and flags thrust high, calls for change universal.

In the Federal Republic of Germany in the 1960s, post war ‘Amerikanisation’, a perceived failure to purge the upper echelons of society of its Fascist past, and a vocal and right-wing press monopoly, generated mass protest in the newly reformed country. This climaxed in a demonstration against a controversial visit from the Shah of Iran, which precipitated the police shooting of student Benno Ohnesorg. Indignation was widespread and led a minority to conclude that the intransigence of the state could only be countered with an armed struggle, theorised with a concoction of Maoism, Marxist-Leninism, Anti-Imperialism and Third Worldism.

The Red Army Faction (RAF) was spawned from this unrest, led by the delinquent Andreas Baader; Gudrun Enslinn, a pastor’s daughter; and Ulrike Meinhof, a journalist raised by intellectuals. In 1968, the RAF detonated a bomb in a Frankfurt department store, catalysing a decade-long battle between the generation who lived through 1945 and their offspring. This is what Arwed Messmer’s body of work, and publication, RAF: No Evidence / Kein Beweis invites us in to observe and for which he was nominated for the 2019 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize.

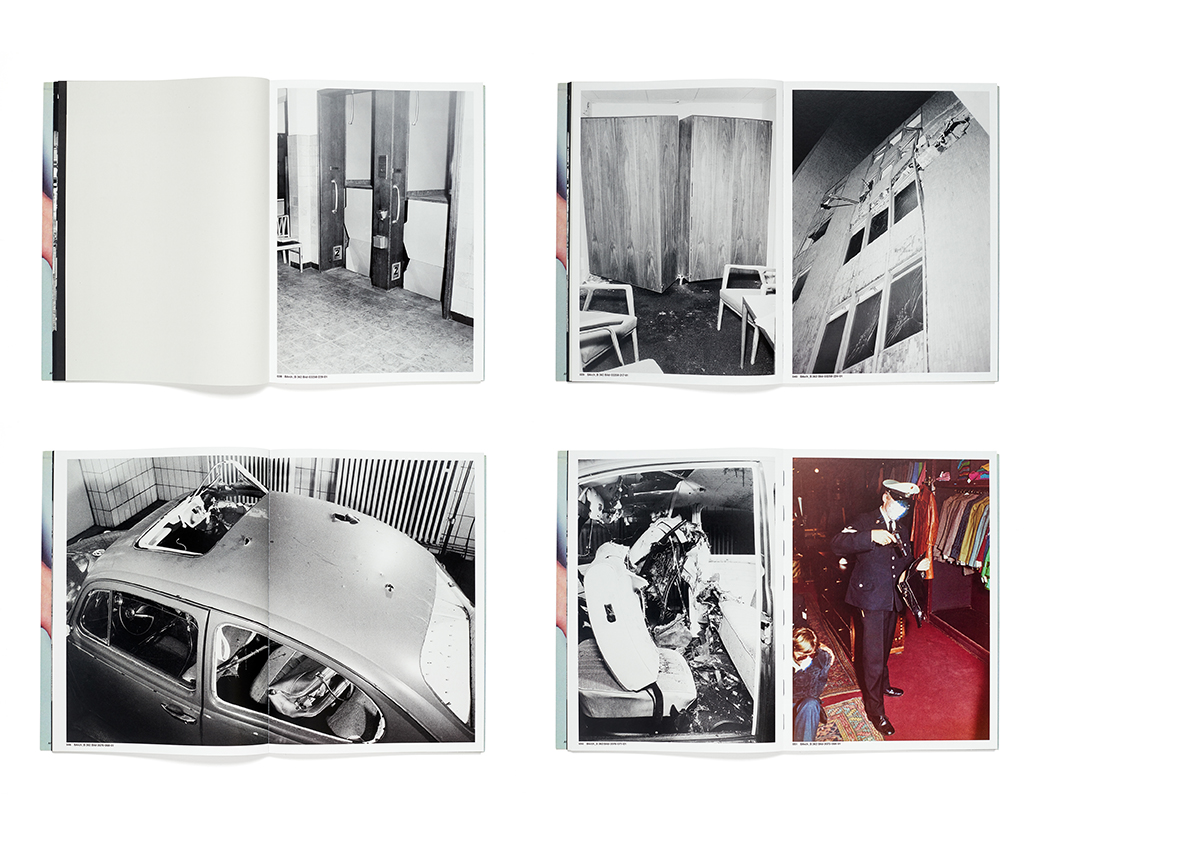

The selection of hundreds of images that Messmer – an artist whose oeuvre threads together recent German history through archival images and his own photography – has compiled, takes the viewer on a pictorial speed date with one of the most violent and tumultuous periods of 20th century history. The tumbling, Levi-clad Andreas Baader as he is folded into a police car and mugshots of goofy yet angrily politicised students sit alongside images of blood-spattered, bombed out car wrecks, police cells and prison cells, terrorist cells and portraits of the fallen. The images, a mixture of black and white and colour, come from both sides of the urban battlefield that the RAF and the West German state wrestled upon for more than a decade.

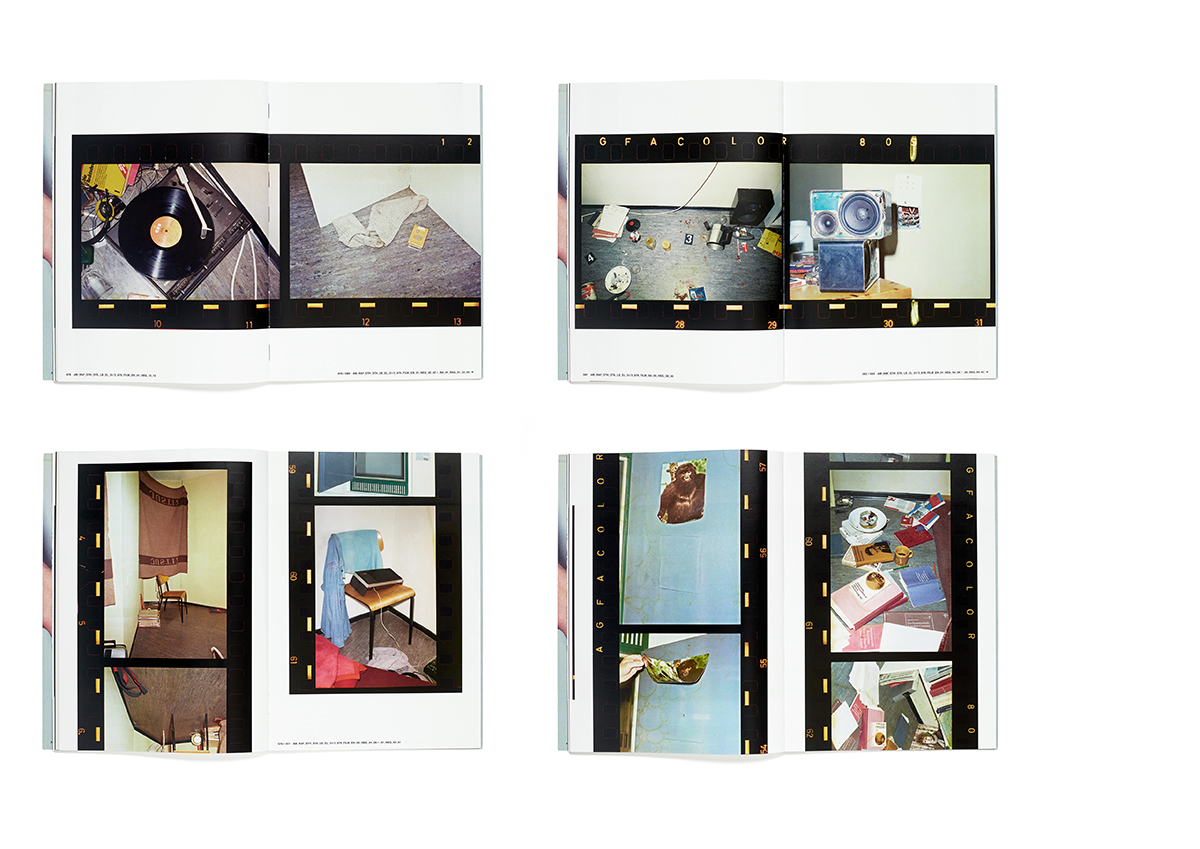

Numerous creative works have engaged with the legacy of the RAF, from its first moments of aktion through to the deaths, kidnappings, and hijackings to the German Autumn of 1977, where matters came to a bloody crescendo. Notable are Gerhard Richter’s series of paintings October 18, 1977, and The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum, Heinrich Böll’s allegorical novel on violence and liberty. Photography also canonises aspects of the RAF story, such as the book by member Astrid Proll, also a photographer, who published Hans und Grete in the late 1990s and Hans Peter Feldmann’s book of media death masks, Die Toten. Whilst the visual history of the RAF may already therefore be familiar, Messmer’s project comprises rarely seen photographs – taken by police or state photographers in the late 1960s and 1970s as evidence of RAF activity – that he uncovered in the Berlin Police Historical Collection and other West German governmental archives. He asks us to consider what happens when a series of surveillance photographs and negatives are made public and juxtaposed with vernacular photography of the time, including some of his own photos of RAF ephemera.

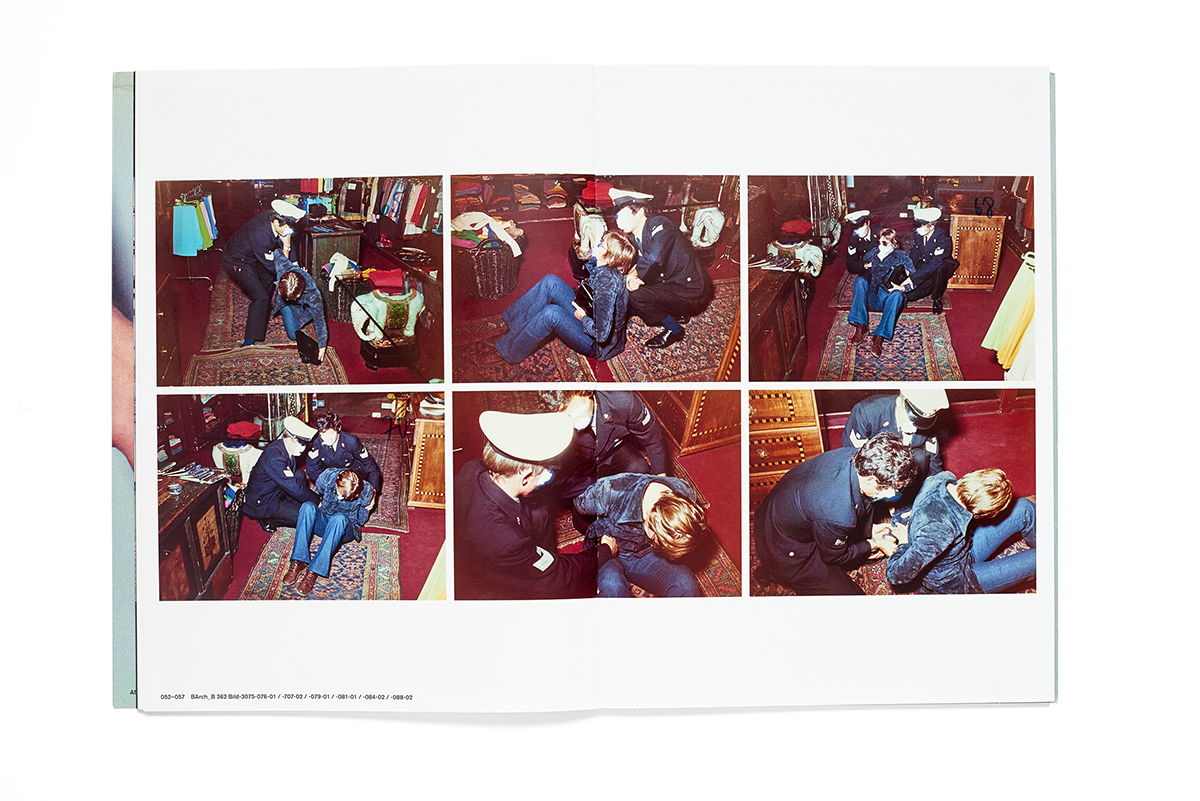

Messmer was first attracted to these rarely explored archival photos after seeing a shot of the sandy suede boots worn by the gunned down activist leader Rudi Dutschke, perhaps fitting for a project that tells the story of what grew out of the student left. Clownish, cheeky, colourful mug shots from the late 1960s that have been gathered by Messmer which draw us in to how it all began. Student protestors, including Baader, dressed in outfits with Surrealist touches, smeared in make-up and donning comedy hats epitomise the start of a new, post-hippie era as they are cautioned for mild agitprop . The protesters, opposed to the ossified Communism of the East and suspicious of the centrist government at home, did not go far enough for some. The RAF was soon to replace demonstrations, pranks and individual acts of mischief, with a disciplined assault intended to unmask the ‘Fascist’ state and bring it down through urban guerilla warfare.

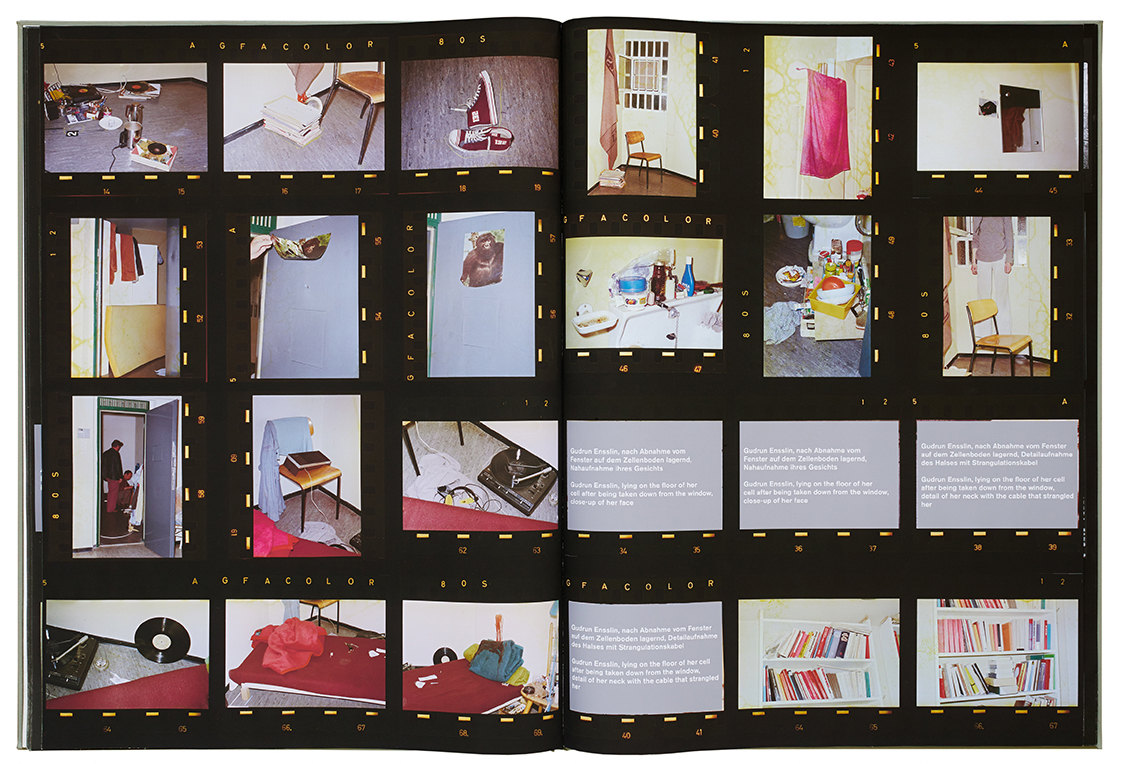

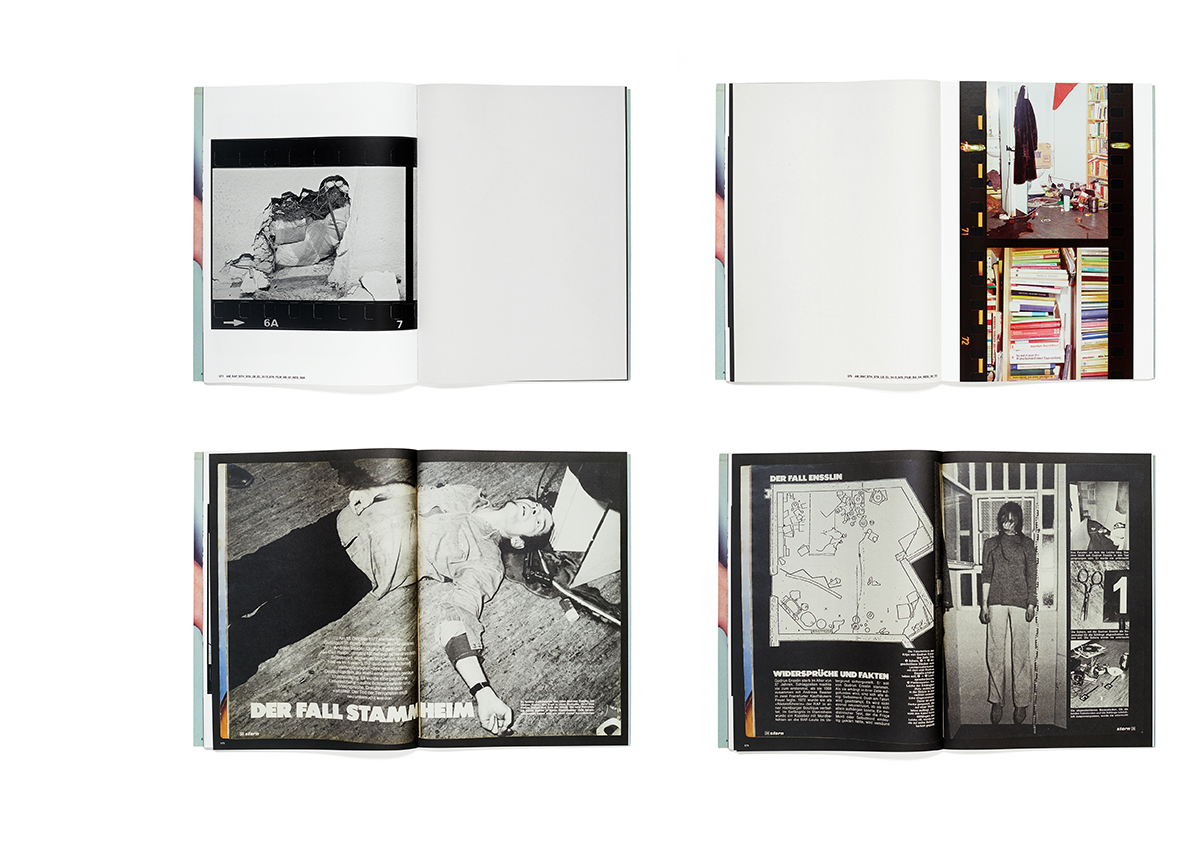

In Messmer’s gathered images, just some of the thousands taken by the state, the counterculture roots of the RAF are clear. The viewer observes an assemblage of the RAF’s belongings which could have been those of any young persons at that time, Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde, black coffee (half drunk), Marxist books and bashed up socks and sneakers. These are the pictures that Messmer takes from the police archive of a Frankfurt RAF hideout and of the police cells that group members were kept in. In reality, even seemingly trivial images were snaps gathered to keep as evidence of a criminal presence. In Messmer’s decision to display them next to the photographs of the RAF members as published in Stern in 1980, it becomes apparent that the RAF, despite retaining high approval ratings among German youth for their early activities, took a different path to other young counterparts. Their deaths were in the Stammheim high security prison, their lives taken by (apparent) suicide at the end of a decade long bloody battle with the authorities and the right wing media.

Messmer challenges us to reconsider the power in the hands of the RAF and that in the hands of the media at the time, showing us widely circulated images in a new framing. For example, he includes a curated selection of the images of industrialist Hanns Martin Schleyer, who was kidnapped and murdered by members of the RAF in 1977. Schleyer appears dirty, bloodied and resigned to death in these staged Polaroids, which were made issued by the RAF and circulated widely to newspapers and television at the time. Elsewhere, one can also see what Florian Ebner refers to as contemporary state-sponsored ‘media brutality’; in the images of dead RAF members willingly published and circulated by the conservative Axel Springer owned media or the state angled shot of the dead Benno Ohnesorg. In the latter, we see a wider contextualising shot of a famous media image, with the press photographer included this time, captured getting his close up of the body along side an agitated woman and several officials, as if in a play, all perfectly staged and performing their own role.

We, the viewer, do not know who gathered or shot the police photographs and likely will never find out. Several images chosen by Messmer feature police officials with their faces scratched out to protect their anonymity. This presumably official defacement inadvertently and ironically chimes with the mindset of the RAF, who saw all state officials as anonymous ‘pigs’ and totally acceptable cannon fodder. Also included is a greying photograph of plans for a police stakeout, marked up with Biro, almost like a target practice sheet, which shows the equally detached attitude of the RAF’s state official adversaries.

The West German state was undoubtedly worried about the threat the RAF posed. In RAF: No Evidence / Kein Beweis, Messmer exposes the viewer to stacks of files about hordes of RAF members, piled high. Thousands of documents, yellowing photos, and dusty clippings, all of them the products of hundreds of hours of surveillance from a nervous government. In exhibition form, No Evidence blows these images up to gargantuan proportions, imbuing them with a vastness that renders them overwhelming.

Messmer also prods and plays with images of the RAF that are already in our subconscious by juxtaposing them with the state images. The poppy cover of Der Spiegel featuring a coy Andreas Baader, the photograph of the dead body of Holger Meins, which recalls both Christ and Che Guevara, and Astrid Proll’s imagery of the RAF members at play in Paris, all feed into the cult of what some have termed the Prada Meinhof phenomenon; the glamourising and fetishising of the group. Messmer’s curation adds a strong dose of reality, as he places these materials alongside photographs from the police archives illustrating what damage a detonated RAF crafted device could do to vehicles, and more importantly its drivers and passengers.

These state sanctioned images were never intended to be seen by the public and are often extremely brutal. Yet some depict moments of real humanity that a documentary or press photographer could wait years to capture. Young protestors are captured hugging and holding hands in one photograph, whereas in another a listless young child stares out of a car as his family drives away from the same demonstration. Shots of the funerals of Baader, Enslin and Jan-Carl Raspe, captured in muted autumnal hues, show both a grieving mother and child leaving the scene, and clamouring journalists and a strained police officer on duty. Dispassionately taking photographs of this scene, our anonymous police snapper inadvertently encapsulates the tension, strain and emotion on both sides, away from the heavy action and violence. Messmer deftly brings this to light. The use of brighter and more sophisticated colour film compared to the first black and white shots taken a decade prior, further adds to an exhausting feeling of time passing and an era lived.

Messmer, an archive archaeologist, pushes the boundaries of how the social history and visual culture of the RAF era can be read, and uses imagery from the police archives to inform, alter, and amend the prevailing right and left-wing narratives of the time. In doing so, he asks us to think again on late Sontagian notions of how one views conflict, and calls to mind Sekulian notions of trying to reconsider or view history from the perspective of the silenced. In this instance, however, one wonders who the silenced are.

Read more Photography+ Learn more about this artist