“The most terrible thing is your own judgment” - Robert Frost, Atlantic Monthly, June 1962

Some of the first music I owned was a collection of cassette tapes entitled “Now That’s What I Call Music!”, an annual anthology of popular tunes that until my early teens, marked the passage of time with a musical blend that included the likes of Milli Vanilli and Los Lobos. Eventually, I came to realise that much of what the tastemakers at EMI considered Music! was the aural equivalent of artificial sweetener. Tastes change and despite the pundit’s claims, many of today’s great photo books will disappear under the wave whose crest brought them to our attention.

Attempting myself to define a “good” photo book, I could evoke a triangular equilibrium of fundamental properties: Concept, Construction and Content (see fig. 1). The problem, is that any attempt to identify how each of these qualities should be assessed, would eventually need to concede a role for gut instinct. As my gut is fed on complex soup of personal and acquired experience, it presents a thoroughly unsound foundation for a reliable set of criteria.

How then could we judge what makes a photo book “good”, without falling foul of the vagaries of modern taste or our own perceptions? According to literary scholar Franco Moretti, ‘If we want to understand the system in its entirety, we must accept losing something’. In place of closely examining a handful of canonical works, Moretti suggests that we apply a process of distant reading, examining entire genres of literature as an evolutionary biologist or economic analyst might sift through data, searching for patterns that will yield a hypothesis.

What happens then, if we apply a similar approach to photo books using the feedback mechanisms incorporated into most online retail spaces?

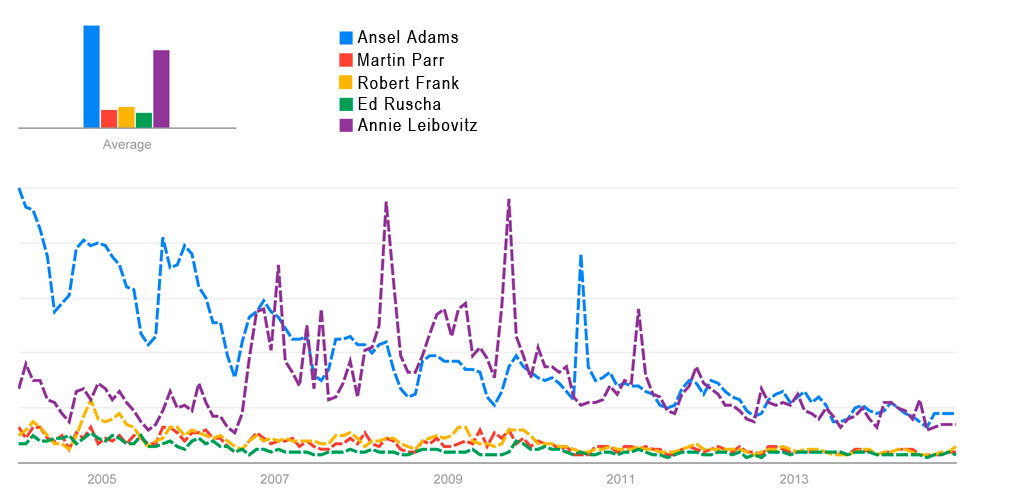

At time of writing, Amazon’s UK website lists 111,323 books under the tag “Photography”. Using its “sort by customer review” function and dividing the resulting top 100 books into categories, an interesting pattern immediately emerges (see fig. 2). The overwhelming majority of books are of an instructional nature (almost a third) followed by photographic publications that offer the reader what could be described as a vicarious experience, travelling to Victorian London or visiting David Bowie’s dressing room. Whilst some of these books exhibit a sophisticated consideration for aspects of design and an attempt to transcend their stated subject matter, the majority do not. The books that do, I placed into a catchall category of “Art/Documentary”. Some familiar names feature: Eugene Atget, Martin Parr and Robert Frank for example, whose The Americans takes 80th place. Only one canonical photographer has two works in the list, Ansel Adams.

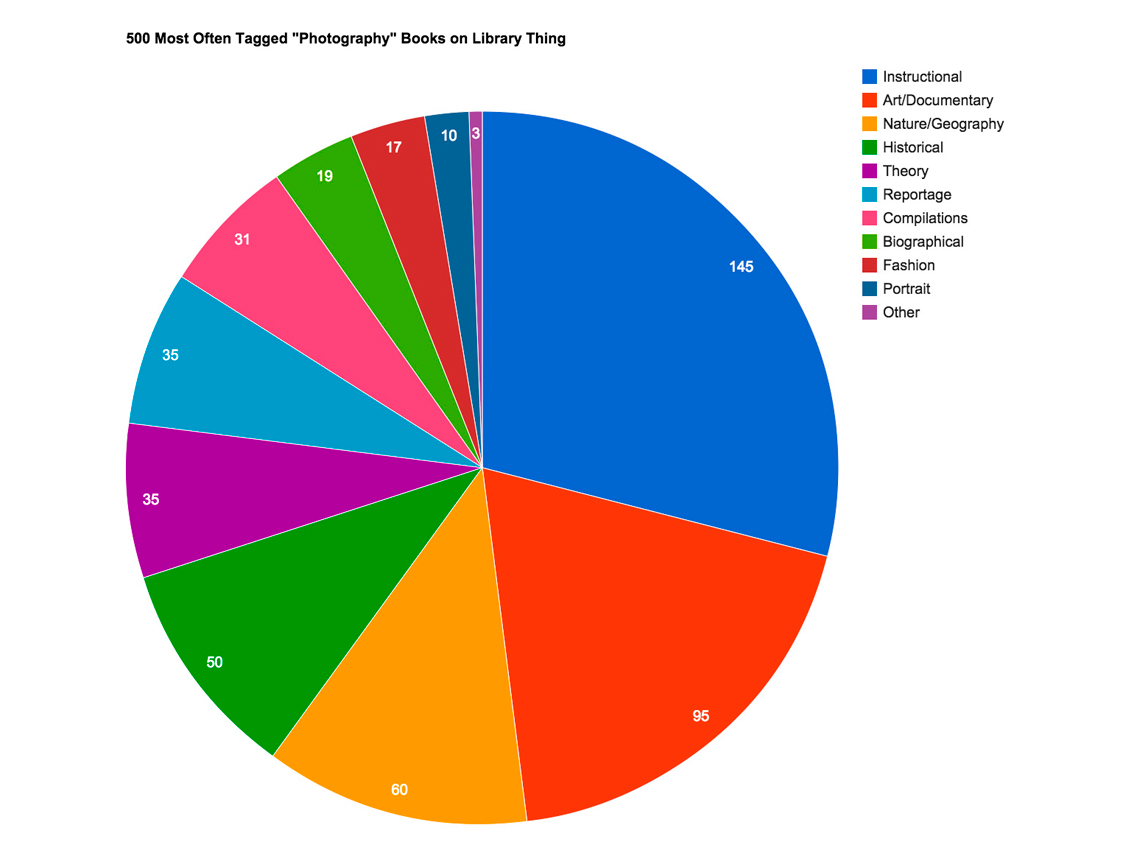

It could be argued that Amazon provides too general a sample group and fails to acknowledge the role of the connoisseur or specialist. In order to do this I have consulted the website Library Thing, which allows bibliophiles to create an online catalogue of their libraries. A number of well-known photo book collectors and small institutions catalogue their books here and a search of books “most often tagged photography”, delivers a somewhat different picture (see fig. 3).

In this case a larger sample of 500 books is taken, so that a book only needs to have been tagged 22 times to appear in the results. Although instructional books maintain a similar share of the result (27%), Art/Documentary books have gained considerable ground. There is naturally some subjective interpretation in my allocation of books to specific categories, for example William Wegman’s dogs and Karl Blossfeldt’s plants go into art, whilst Hans Silvester’s Cats in the Shade goes into Nature/Landscape.

The same canonical names crop up, this time joined by others, such as: Annie Leibovitz, and Dianne Arbus, theorists also join the ranks with Susan Sontag’s On Photography tagged more than any other book. Once again Ansel Adams appears more than other photographers (five books in the top 50 alone).

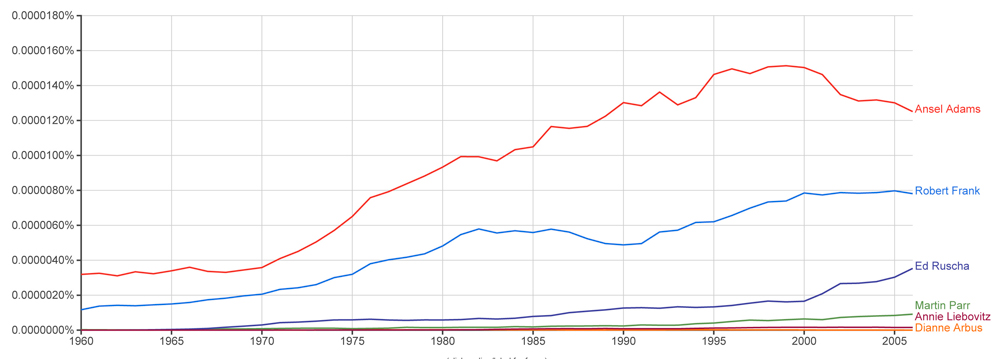

Using Google Ngram to search the millions of books digitised by Google, we can get a better sense of the scale of Adams’ popularity by seeing the percentile of all books scanned that feature his name and that of other photographers (see fig.4).

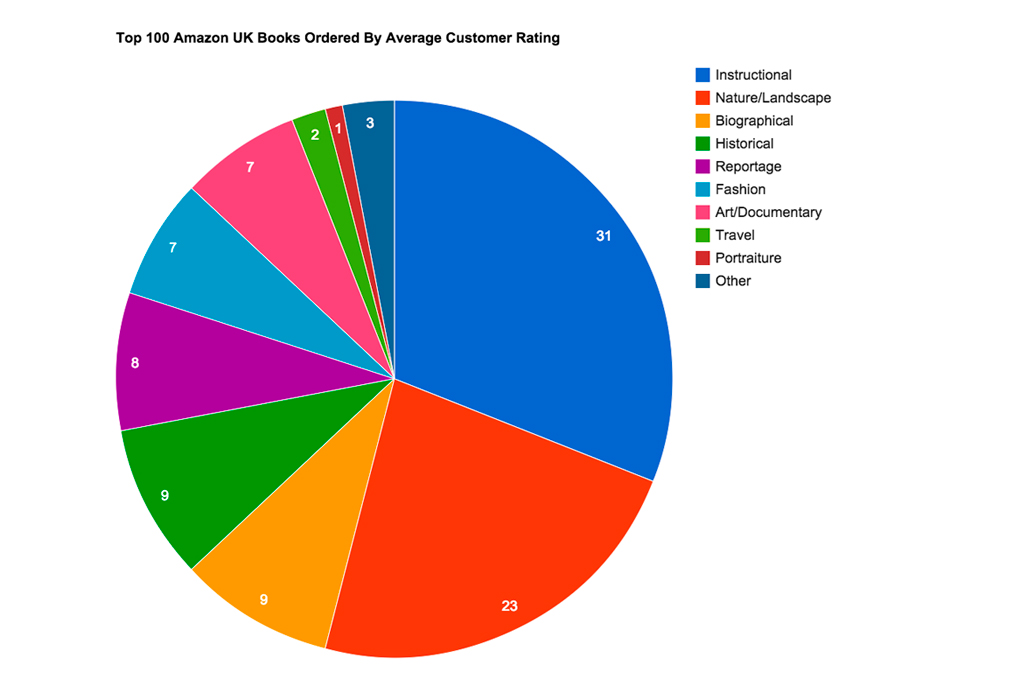

Google Trends returns similar findings, although this time tempered with a significant level of interest in Annie Leibovitz. (see fig. 5). Interestingly, the results for the three other artists, all of whom are in one way or another synonymous with the modern “photo-book”, cluster toward the bottom of the chart, rising and falling in approximate congruence.

The relationship between the three very different practitioners suggests the existence of an esoteric “photo book” genre. Therefore even Library Thing could be considered too wide a net to cast, it has after all over 1.8 million members.

To truly take on board the views of the connoisseur and the collector, whose activities might present the smoke trail of a good photo book, we must turn to a more definitive list, AbeBook’s The Ten Most Collectable Photography Books of All Time. Here finally, we see no instructional manuals, no homages to ponies or kittens, no Photoshopped celebrities, just classic photo books. There are certainly some wonderful books: Evidence, Paris de Nuit, Twenty Six Gasoline Stations and yes Ansel Adams appears once again, but do these books have something in common, other than their rarity and hefty price tags? Nearly seven hundred years ago the Italian scholar Petrarch finding it hard to obtain copies of important manuscripts complained:

“There are those who decorate their rooms with furniture devised to decorate their minds, and they use books as they use Corinthian vases or painted panels and statues.”

Ultimately, the answer to the question “what makes a good photo book” is elusive, it should be, for each new set of eyes a book is reborn. What is interesting, is that a very small number of books appeal to a broad number of people and simultaneously, in their original editions, to collectors. Paul Valéry once suggested that the history of literature should not be seen as a catalogue of authors and their works, but as, “a history of the Spirit as producer and consumer of literature”, perhaps one day we might be able to say something similar of photography. Our urge to atomise and fetishise the medium is a result of times we live in, where everything must be seen to have a value.

There are no good or bad books, only ones that excite us, bore us, frighten us, anger or teach us. No act of looking is ever wasted and to believe that we must adhere to a set of rules or ideals in making a photo book, is the only way we might come close to making a bad one.

Text by Louis Porter of ABC.