I’m a critic of photography, and have been for more years than it is polite to recall. I should have (in fact I probably do have) a set of perfectly cogent litmus-tests which I apply to photographs.

Among my recurring mantras, I acknowledge the simple efficacy of Mark Twain’s brutal: “If you have nothing to say, say nothing.” There are far too many pictures in the world, and it’s the work of a moment to spot the ones that say nothing. Having something to say really is a good start; it’s a communication medium, after all.

I have always been irritated by photographers who are illiterate in their medium; and not in a know-it-all Professor of Photography kind of way, either. I don’t mean that everybody has to know what an ambrotype is or the date of birth of James Jarché. I mean something much less dry than that. In other art forms, creators gauge the level of knowledge of the audience and build upon it. Put another way, creators know that their audiences work hard to extract meaning and emotion from their stuff, and they pitch it where that effort can be rewarded. Thelonious Monk most assuredly knew the simple cadences of the Protestant hymns which underlay the classical chord-sequences of the piano blues that came before him. He didn’t want to play like that, but he knew that his audience knew it, and he could quote and refer and paraphrase and make fun of that stuff confident that his hearers would ‘get’ it. That is literacy.

I’ve always pleaded that photography is a perfectly ordinary cultural activity. What that means is that it has to respond to analysis. Photographs are good or bad for understandable reasons. That should be an article of unshakeable faith. But in every other culture that I know, citation and reference and parody are the absolute basis of communication, and unpicking them the basis of analysis. Somehow, in photography, we often allow that to slip. So many photographers think that they are inventing the wheel, and that their viewers can be ‘wowed’ by their lonely vision, isolated from all that went before. It isn’t so, and it shouldn’t be so. If photography is a cultural activity, then those who engage in it have to own to a culture. It need not be that of the conservatoire or the museum, of course not; but without one, they can only reach audiences by chance. That is the cost of illiteracy.

So I do have a number of criteria that I apply to photographs.

Without hesitation I second a number of the things said by my predecessors in answering this question for Photoworks. Martin Barnes says ‘Good photographs neatly express the obscure and complex meeting point of illusion, reality and theatre,’ and I say hooray and +1 to that. He adds ‘When made with skill and sensitivity they inhabit the wonderful hinterland where perception and imagination meaningfully collide,’ and I throw my hat and call Hear Hear to that. Lots of other phrases from this series chime like that with me.

But this is a discussion forum, and I want to put down something of which I am much less sure than the various tropes and tests by which I sift and sieve the pictures that come before me.

I am increasingly coming to the view that good pictures are in fact made by their users and receivers and viewers, and not by their makers. I think this is where the phenomenal spread and reach of photography have got us. I think it is the more true in the super-vernacular digital age of Instagram and “likes” and stupid graphic thumbs-up symbols but I suspect it has been true all along.

It is certainly true now that there are so many pictures that a viewer makes his or her own way through the minefield. In the not-very illuminating jargon, the archival habit in photography has come more to the fore. We are all necessarily archivists of a sort, because so many photographs come to us unmediated. Editing for one’s own purposes is the norm. We all make selections, willy-nilly. Lots of people have pointed out that we’re all photographers, now. Julian Stallabrass, in his excellent earlier article in this present series said, ‘If everyone is a photographer, then no-one is a photographer‘. My own partial answer, over a number of writings, has been that we’re all camera operators, but that doesn’t make us photographers. (Still, that’s for another place.) Much more important is that we’re all editors.

The modern version of subscription asks us to edit: I want to see more of this, I want to sign up a regular feed of that. That always happened to some degree; the fact that the volume has changed by orders of magnitude does not mean that the thing itself is new.

Yet there is a decided shift. Three recent shows/books stand out in my mind as showing the way the wind is blowing. All three are the product of refined editorial skill at the highest level, and therefore serve as examples of ‘high practice’ rather than examples of the current norm, but still. It is amazing that all three should have been produced so close to each other.

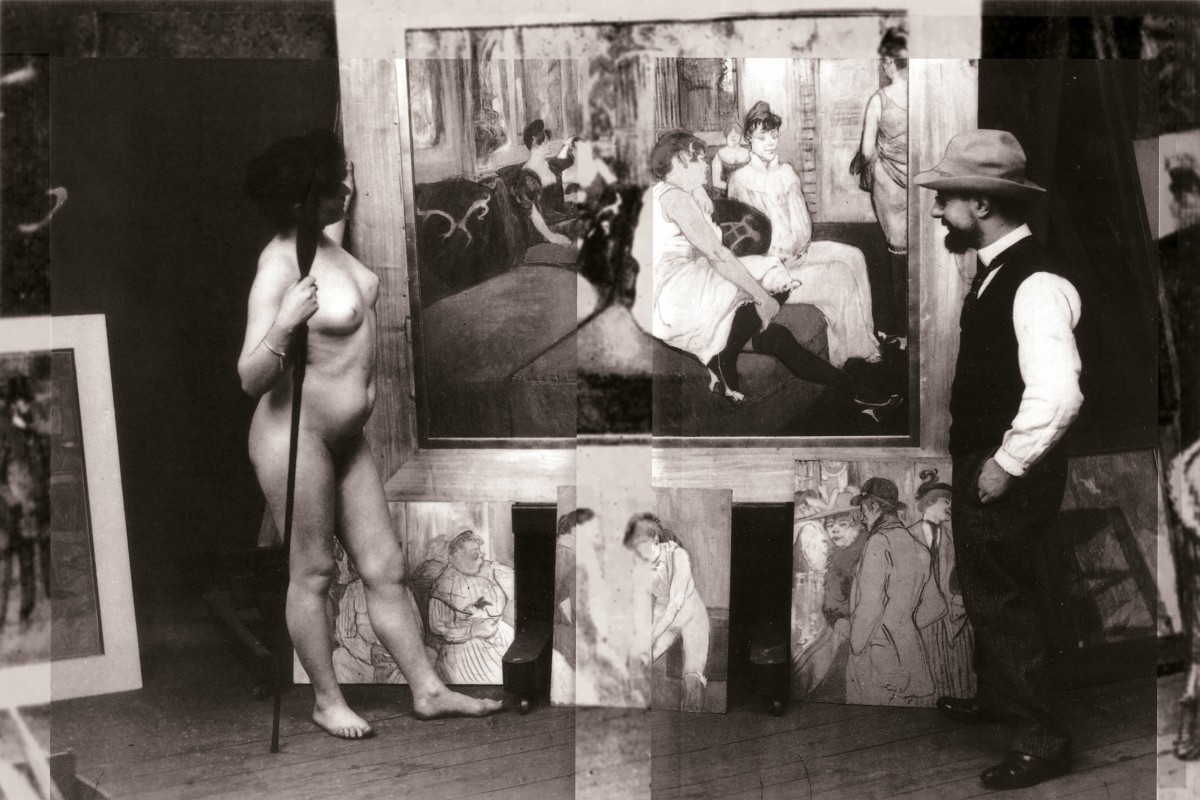

La Photographie en Cent Chefs-d’Oeuvre was a show which closed a year ago, in February 2013, at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. It was curated by Sylvie Aubenas, the head of the photographs department there, and by Marc Pagneux. It was a staggering group of physical objects. I remember the glow of deep, deep albumen prints, and the glitter of metal and the glorious way in which a hundred photographers had moulded and bent light to their needs. But you expect that. It’s the BN; they hold a lot of good stuff. What was really amazing was how many of the pictures were not necessarily great images, but were made great in that hushed environment, with the best lighting and careful sequencing, explanation, and so on. I’m thinking of literary and artist portraits, such as a deeply ponderous one of Toulouse-Lautrec with a model. The curators in effect sidestepped their own question. They did not find one hundred masterpieces of photography. They declared a hundred masterpieces. That’s rather different. I remember, for example, a Charles Aubry study of ivy, an albumen print from a wet collodion negative on glass, from 1864. That is only a masterpiece if the intellectual content of a picture is discounted. It’s old, and it’s technically perfect, a piece of virtuoso printing, followed by years of equally virtuoso preservation. But as to content, it’s no more interesting than those much-despised camera club pictures of a ‘perfect’ drop of dew falling off a ‘perfect’ rose. There was even a mid-nineteenth century picture of a fluffy cat, by Auguste Vacquerie, as though the curators were laughing at their own presumption in claiming to identify masterpieces.

The others were the recent books culled from their collections by the English gallerist Michel Hoppen (Finders Keepers, Guiding Light, 2012) and the (former) US gallerist, Bill Hunt (The Unseen Eye: Photographs from the Unconscious, Aperture, 2011). Both men are supremely confident in their own taste, of course, and quite properly neither gives a damn whether a picture is by a photographer known, a little known, or unknown. So both assembled books where ranking in the history of photography mattered not at all, and both books were laid out in such a way that the comments of the collector were the only justification for inclusion. As a result, every reviewer called these books quirky, but maybe they weren’t that. Hoppen is more of a formalist, although quite open to the frankly weird. Hunt is more of a sentimentalist, his theme being that if you can’t see the eyes in a picture you get some sense of the unconscious. Certainly a WM Hunt or a Michael Hoppen can make a picture where was nothing before. Certainly, every single image in these three books now has a place in the history of photography, even an anonymous autopsy of a crocodile. But they also have places in the memories of the people who saw them. Even a little picture can be a big picture to me.

At a less rarefied level, isn’t that what we all do all the time? We have become suspicious of mandarin thinking in many fields. The internet has weakened the role of gate-keeper to knowledge and allowed much more direct access than there used to be. It’s the age of DIY. In something like photography, where access to the material is not the problem, that’s not just a question of having very good cameras on our phones. It’s that we have all become our own in-house curating and collections teams. That’s the thrust of Marvin Heiferman’s Photography Changes Everything, that once a picture or a group of pictures matter enough to anybody, they acquire an importance which is not necessarily implicit in what they are, but in what that person makes them. I’ve written about mattering elsewhere, about how tricky a word it is, and how central in photography. But I think we can formulate it more succinctly than I have in the past. In the new photography, all that matters is that it matters. To somebody.