From issue: #21 Thingification

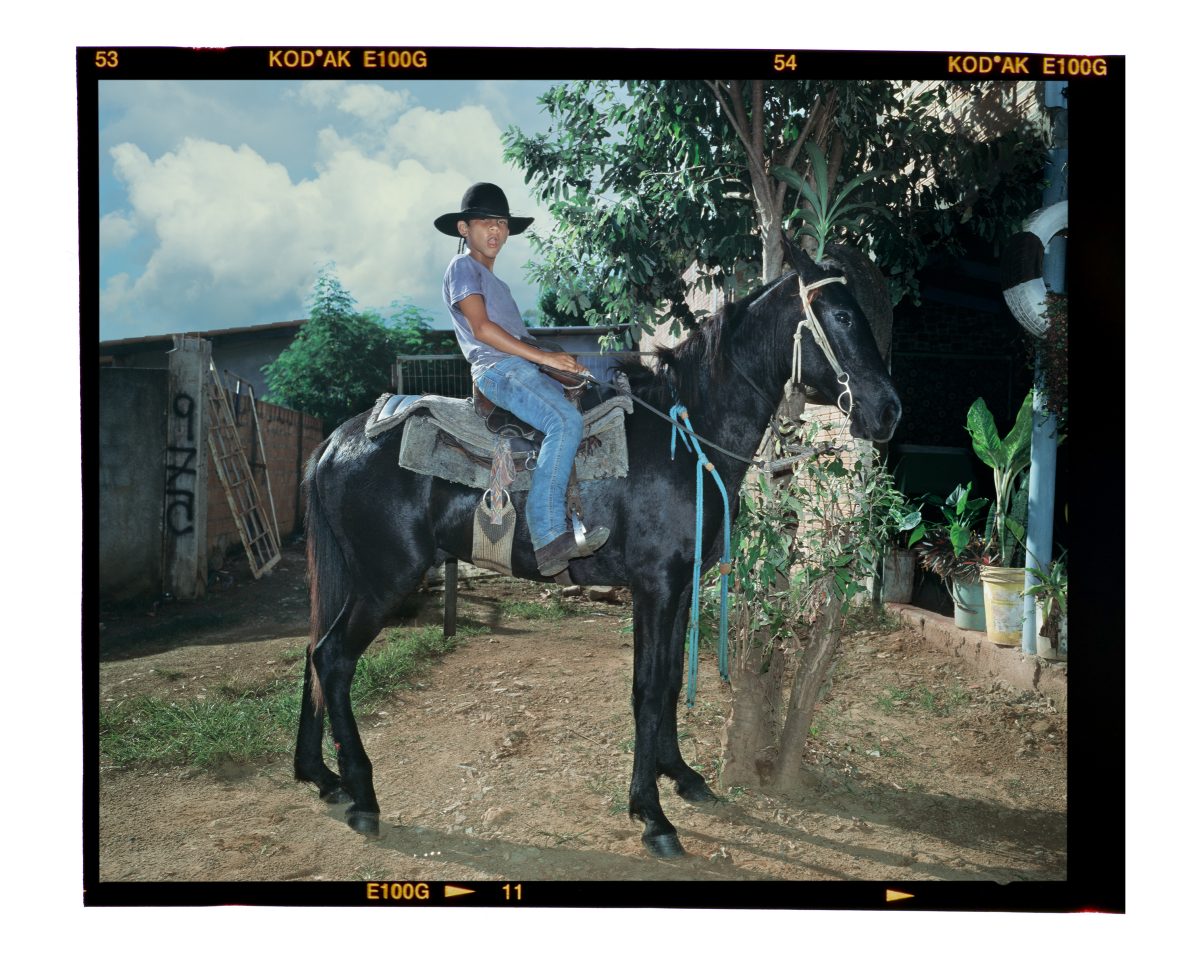

Brazilian photographer Emilio Azevedo is now based in the Ecole Nationale Supérieure de Photographie in Arles, France, but his project Rondônia is a look at the Brazilian rainforest and a new way of engaging with the territory imposed during Western colonisation

P+: How did you get into photography?

Emilio Azevedo: Photography has always fascinated me – as a child, before I was told how it actually works, I found it magical. After school I studied photography in quite a technical way, then worked in the image industry until, at the age of 29, I found I wanted to reconnect with this sense of mystery. Moving to Madrid, I went back to art college and was lucky enough to meet teachers similarly driven by photography’s special relationship with space, time and what we call ‘the real’. From there, I went on to study at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure de Photographie in Arles, France.

P+ : What is the project you are making on the Amazon, Rondônia ?

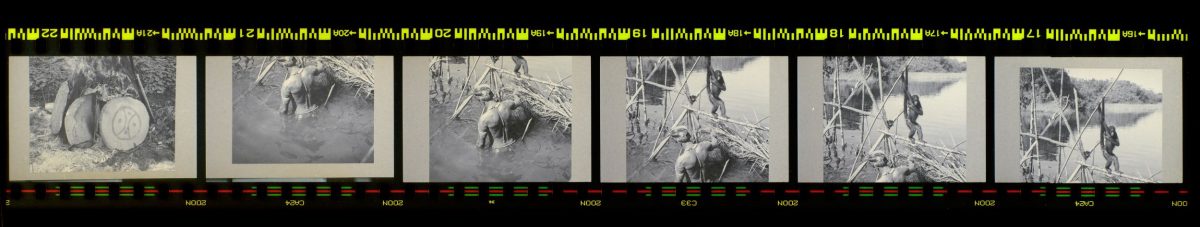

EA : When I started this work I was looking at the Brazilian army, trying to understand its role in contemporary Brazil. Then, as often happens, I discovered something more exciting along the way, It was October 2019, Bolsonaro had recently been elected president, and I was working in a military academy in Rio de Janeiro. In the academy’s somewhat decrepit military museum, I came across archives recounting the ‘development’ and ‘civilization’ of the Amazon, led by the Brazilian army at the start of the 20th century.

Back in France I submitted a research proposal to the Musée du quai Branly’s Photography Prize, and won. Thanks to the museum’s support, I was able to make a long-term project on the different layers of this story. Beginning in military archives in Paris and Rio de Janeiro, I then travelled to the Amazon region in which they were created, following the trans-Amazonian road BR364 that crosses the western Amazon from south to north.

P+ : Your project includes various styles of photography, why is that?

EA : Over the last century the Amazon has been conquered, dominated, and transformed by hands and machines but also by something much more powerful, profound and intricate – our metaphysics. By occupying this territory, we have brought into it our conceptions of time and space, our myths and humanism, and our relationships to the social body and other forms of life. So in both the military archives and the Amazon itself, I was looking for manifestations and signs of these modern Western metaphysics.

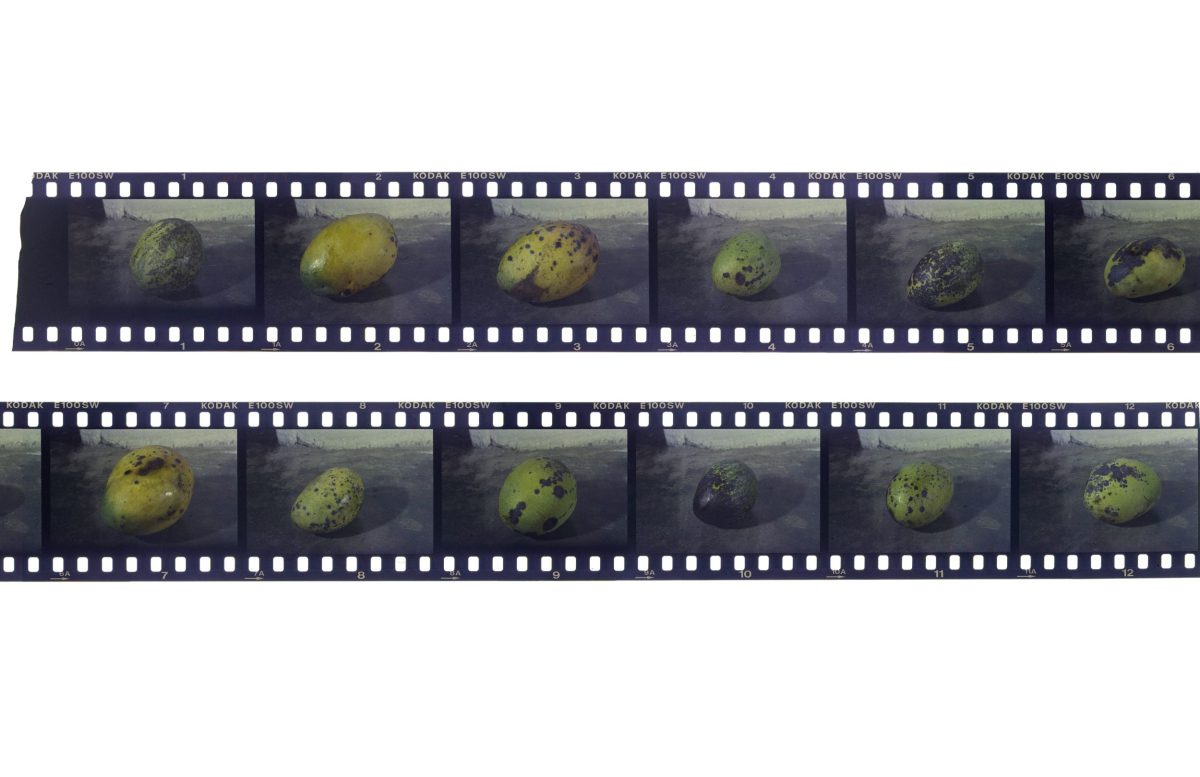

I was very attentive to how this mental framework has shaped and organised the territory, and the different styles of photography are ways of approaching different aspects of this history. I’m trying to adopt a different methodology to that of an historian, journalist or academic researcher, to operate at the crossroads of photography and installation, documentary and fiction, knowledge and doubt. I want to articulate art, philosophy and technique via aesthetic experience, through matter, shapes and colours, and by thinking about the spectator’s body in space and time.

P+ : The three images of flowers are interesting, could you say more about them ?

EA : The flower work is a triptych created in the garden of the Musée du quai Branly in Paris. As with all museums, the Branly maintains a particular relationship with the narratives we collectively form about the past, in its case an ambiguous relationship with French colonial history. When I saw these flowers, in the carefully landscaped garden, I wanted to make an image that escaped this established order. All three shots are taken from the same place, the only thing that changes is the focusing distance but this small variation leads to totally different perspectives and virtually endless framing possibilities. My intention was to use the objectivity of photographic language not to produce evidence, but to emphasise that this clarity is based on conventions, protocols and beliefs.

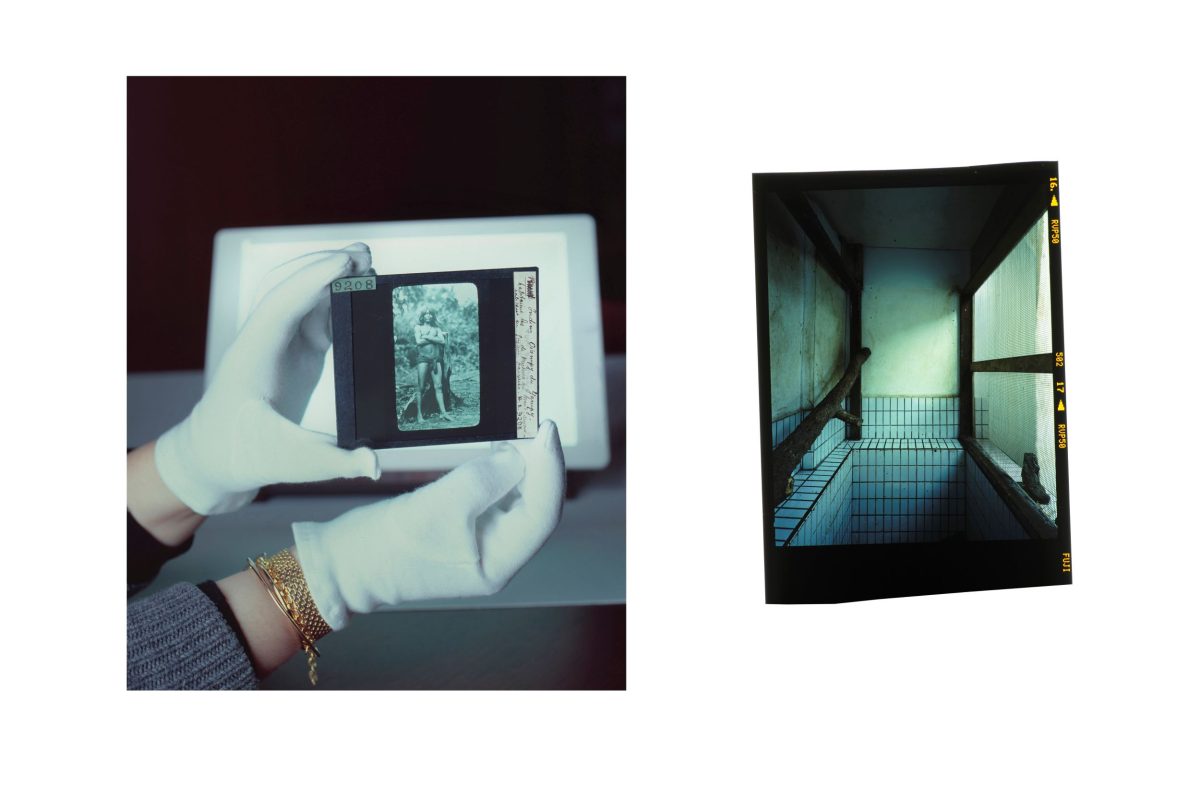

P+ : Some of your images show museum exhibits, is there a relationship between such displays and photography?

EA : Photographic images give us the opportunity to observe events outside the continuum of time. We can calmly study these events, put forward hypotheses, produce thoughts, and even feel emotions. For me, something similar happens in a museum. However virtuous the intention, it is often a matter of isolating and distinguishing events, objects, works, and personalities, creating narratives and an order. In a museum, as in front of a photographic image, we leave the usual course of life and time stands still. But it’s important to remember that actually nothing exists in isolation. It’s all about relationships, and everything is movement and livingness.

P : Your project also includes the route of the telegraph in the Amazon, why is that ?

EA : At the end of the 19th century, the Brazilian State decided to explore and integrate the north-western region of Brazil, located in the Western Amazon close to Bolivia and Peru. This mission lasted for decades and had a huge impact on this area. The BR364 trans-Amazonian route I followed has its origins in the telegraph line laid by the Brazilian military over a century ago, which linked this region to the rest of the country. In this series I was interested in power, specifically the agents of this ‘civilizing’ process, and their frame of mind. For me, these straight lines, in the heart of the Amazon, are emblematic of a certain way of organising time and space. The efficiency of communication, of getting from point A to point B, and of accessing this region’s resources, also say something about the ideas behind this colonial project.

P+: Is there a link between the colonisation of the Amazon and photography?

EA : The colonisation of the Amazon by Westerners spans several centuries, while photography is less than two hundred years old. Photography accompanied a movement that was already underway. But what I’ve found by working in these archives is that photography, in a new and powerful way, helped justify the colonisers’ narrative and validate ‘civilisational’ missions, establishing a hierarchy of life forms and cultures.

P+ : Is there a link between photography and a specifically Western, Imperialist or Capitalist perspective?

EA : Photography was invented in successive steps over several centuries. The Renaissance saw the emergence of new and revolutionary ideas in the West, and with them the idea of a central, static view on the world. This led to the development of observation techniques, which were increasingly adapted to this prevailing perspectivism. The camera obscura, a technological evolution of the simple pinhole, was known since the Greeks, and until the 18th century was sufficient for Westerners’ rhythms and times. But with modernity and the subsequent Industrial Revolution, the precision and rhythm of the painter’s camera obscura were no longer enough. The need, and above all the idea, of a precise, mechanical image emerged. Talbot invented photography, but he was part of a wider zeitgeist in which scientists and enthusiasts across Europe and beyond were working to fix and stabilise camera obscura images.

I think photography is intrinsically linked to Western regimes of visibility and a specifically modern way of organising the world. The photographic medium allows us to establish highly complex relationships with reality. But we might ask ourselves what kind of reality we are talking about and what rules determine it. Photography tells us a lot about what is being photographed, but it tells us more about photographers and their beliefs. By observing archive images, we can better understand the people who made and commissioned them. We can see how image-makers organised the reality they were facing, and therefore learn more about their wider modes of understanding and organisation.