From issue: #22 Group Dynamics

Launched in London in 1983, Format Photographers Agency championed contemporary documentary photography by women – and a co-operative approach to working, explain founding members Maggie Murray, Joanne O’Brien, and Jenny Matthews

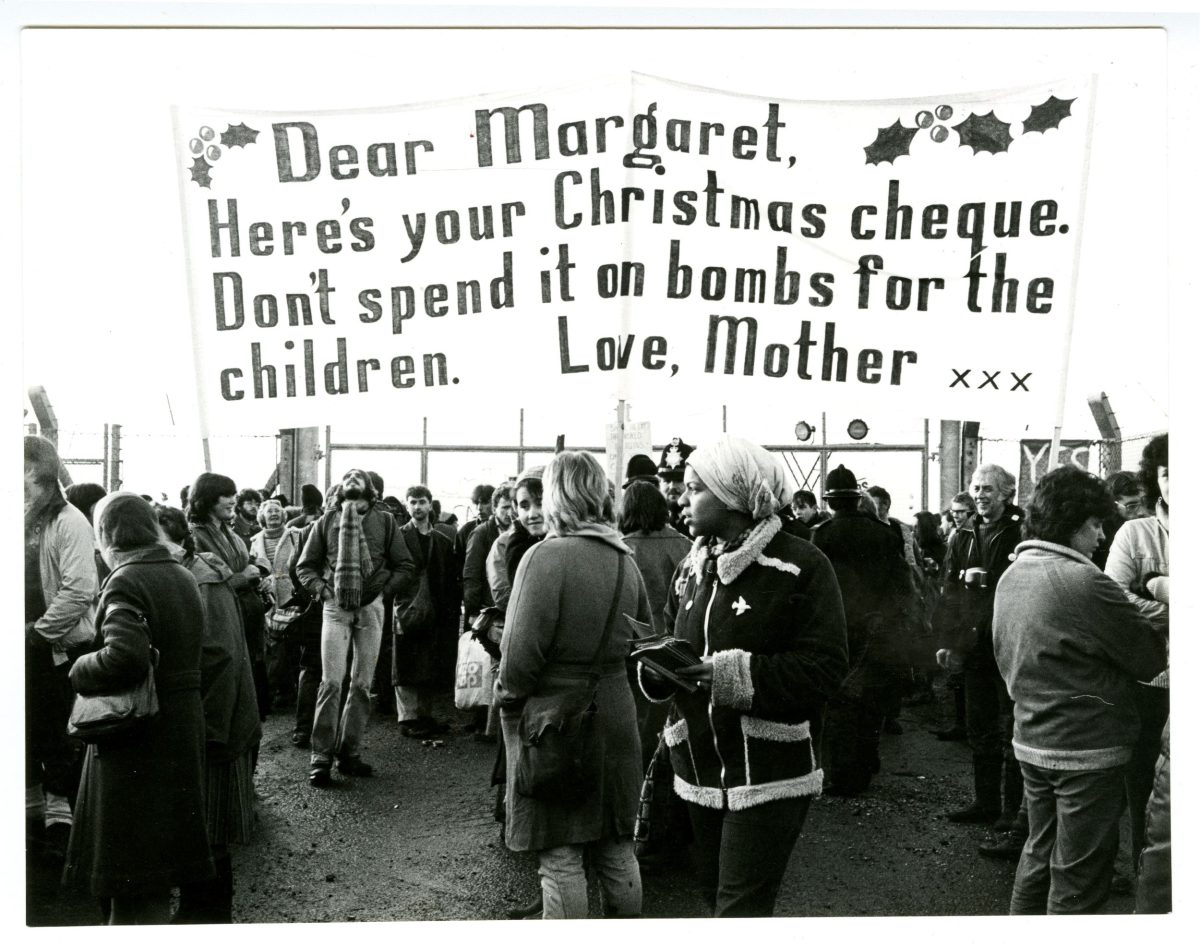

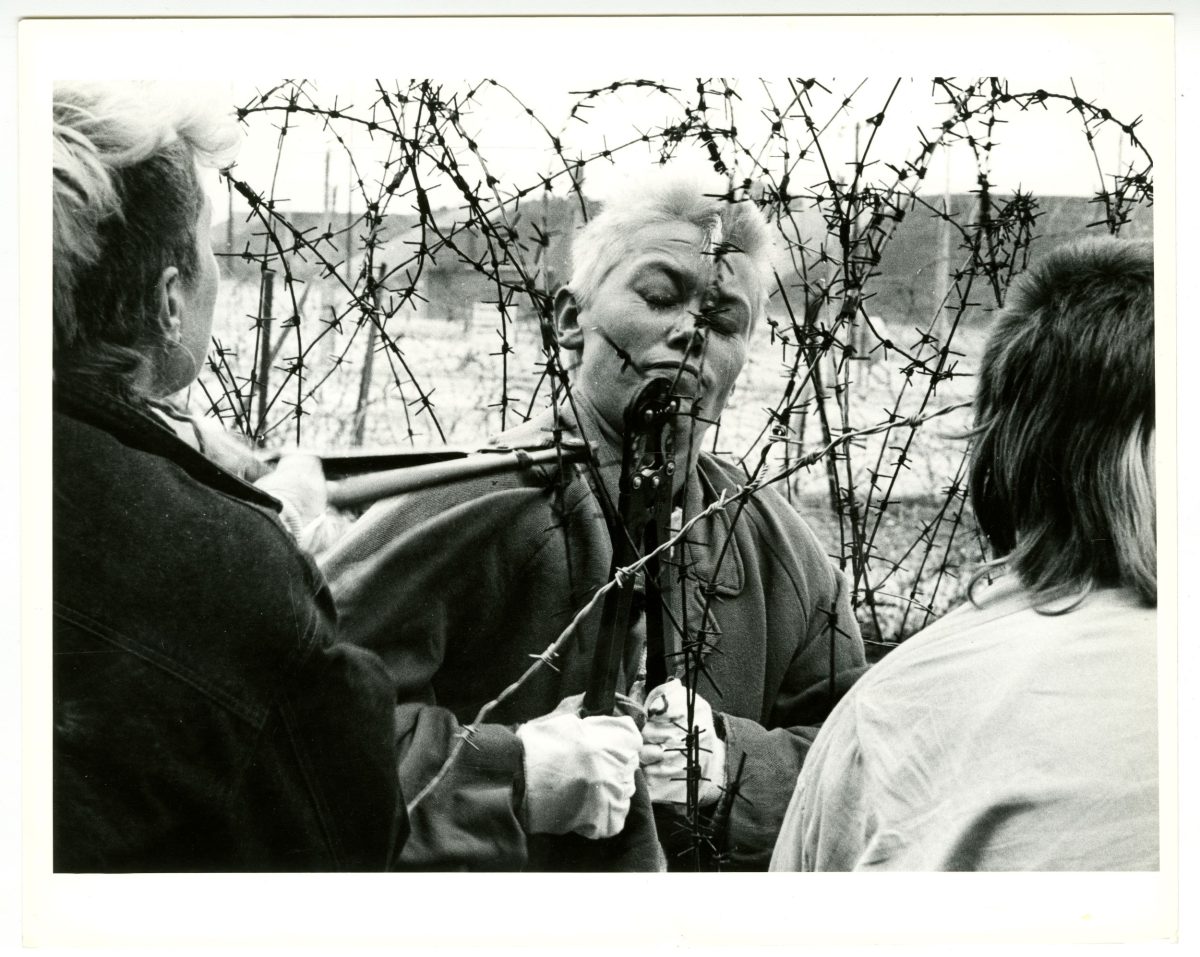

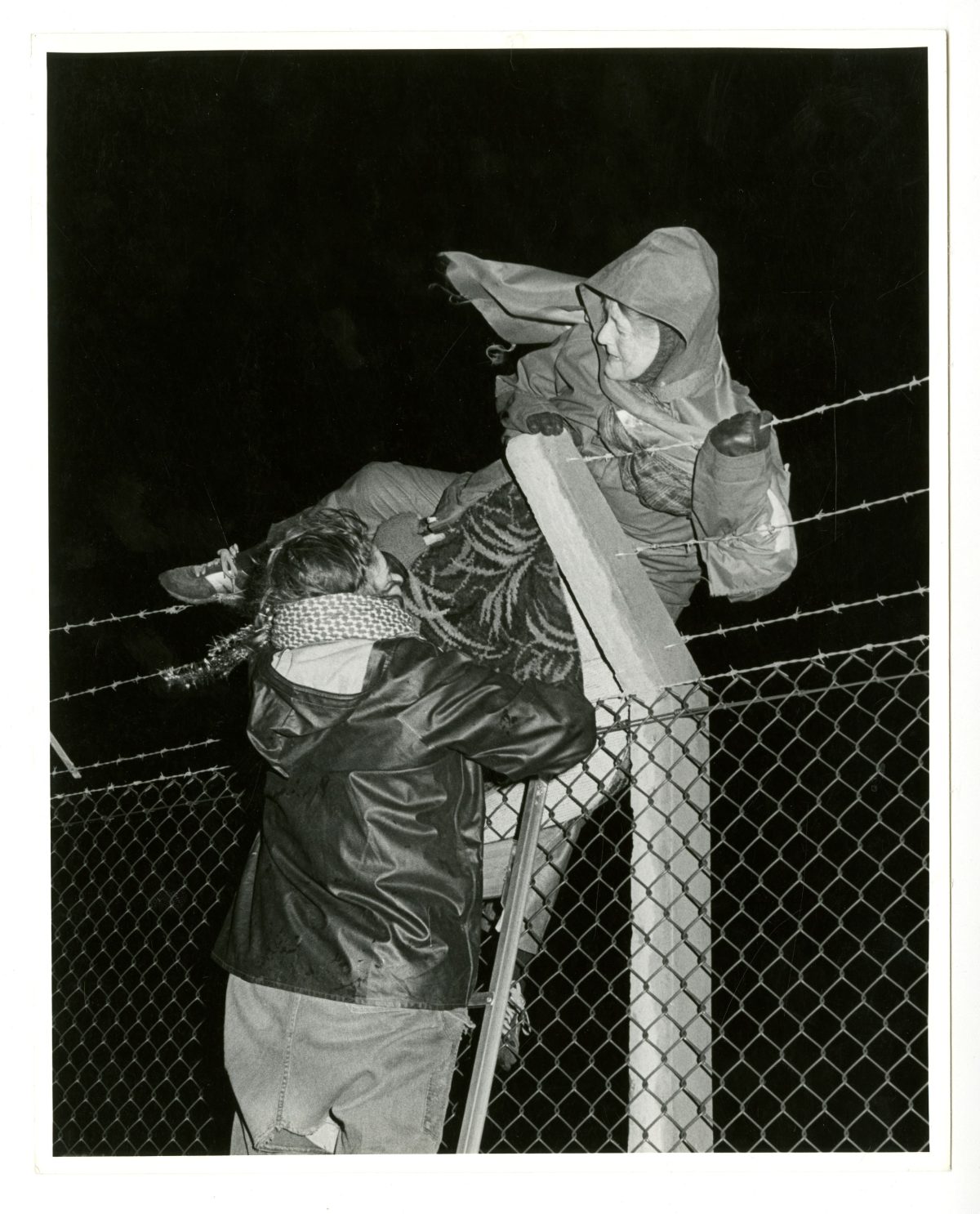

Tate Britain is currently hosting an exhibition titled Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990, a large group show including images of strikes and protests staged by women and documented by the Format Photographers Agency. Meanwhile Re/Sisters – A Lens on Gender and Ecology at the Barbican, a show which explores the relationship between oppression of women and exploitation of the environment, includes shots taken by Format Photographers at Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, a long-running protest against nuclear weapons at a Berkshire RAF base. Both shows are testament to the Format Photographers’ work – though this work wasn’t always welcomed into institutions, and was made with an anti-establishment edge.

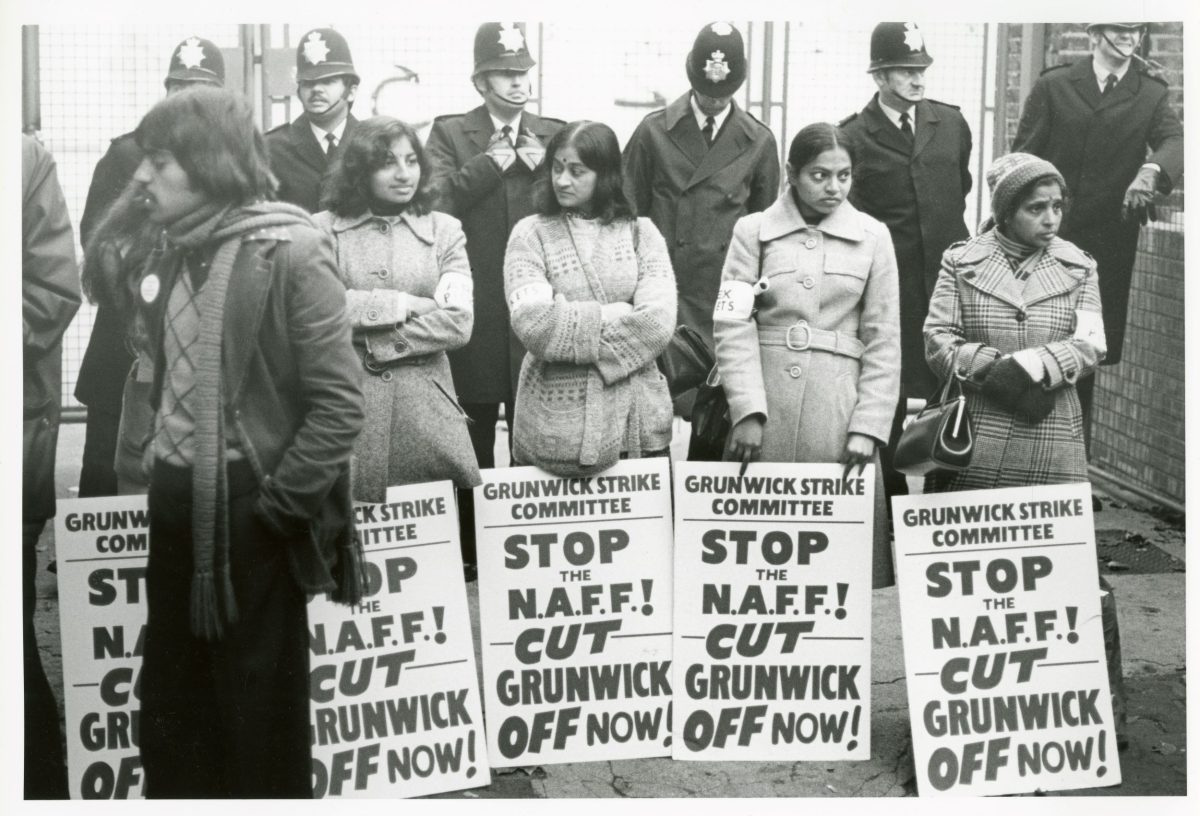

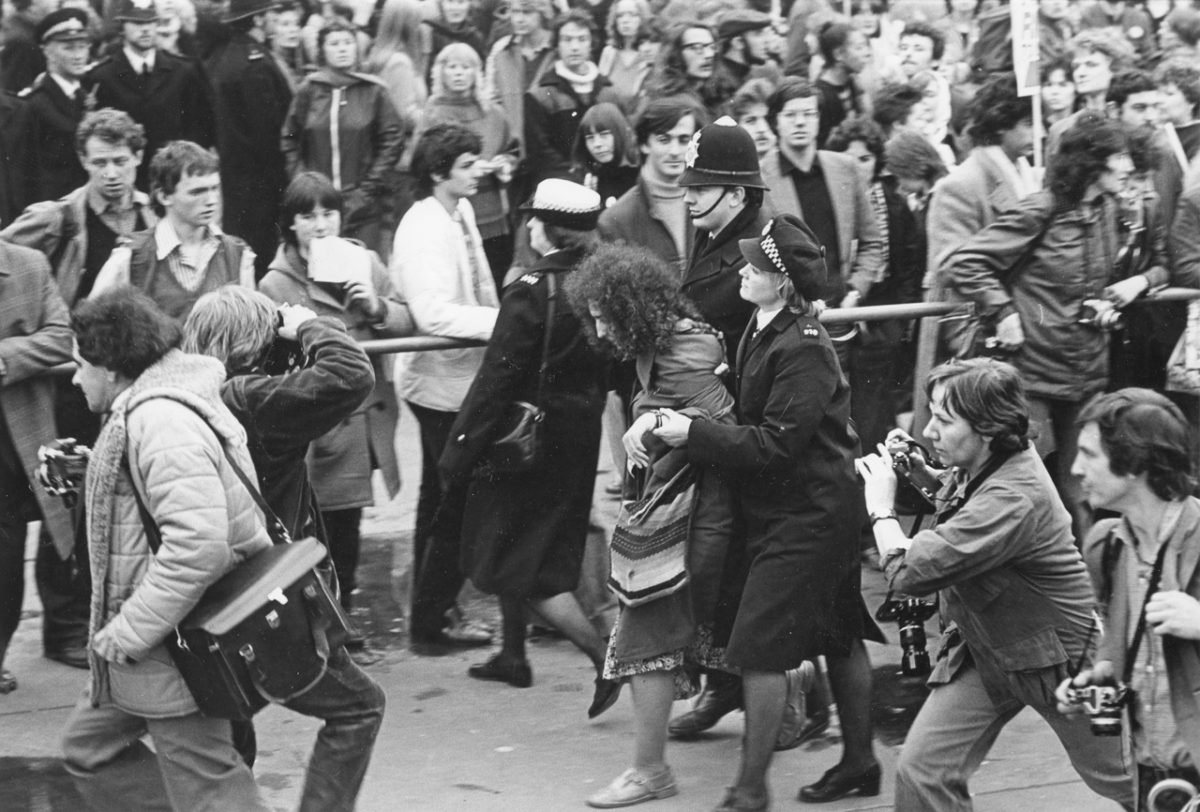

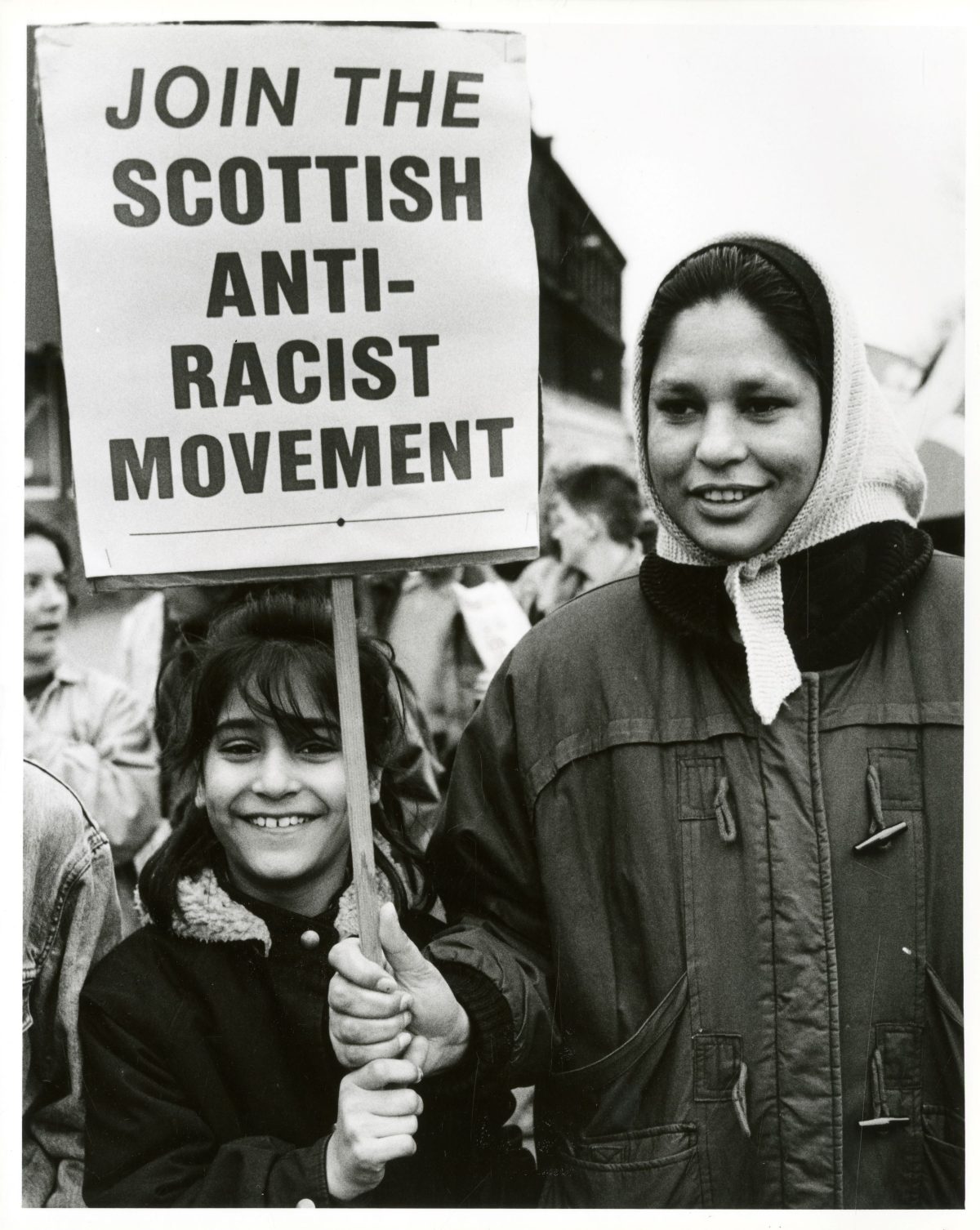

Launched on 11 May 1983 at The Photographers’ Gallery, Format Photographers was the first women-only photography agency in Britain and initially had eight members – Maggie Murray, Joanne O’Brien, Jenny Matthews, Anita Corbin, Shelia Gray, Pam Isherwood, Raissa Page and Val Wilmer. The collective eventually grew to over 20 members and lasted for twenty years, switching from a cooperative to a partnership between Murray and Brenda Prince in 1989 but continuing to represent members until 2003. Format was radical because it only included women photographers, at a time when men dominated the profession and, as the exhibitions at Tate Britain and Barbican attest, it documented women-first UK protests such as Greenham Common, Reclaim the Night marches, nurses’ strikes, women’s activities in the Miner’s Strike, and many more.

But Format also documented activities outside the women’s movement, including marches around LGBTQ rights and Anti-Apartheid Movement, and everyday scenes showing people beyond the stereotypes, in Britain and beyond. Their work was published in newspapers such as Sunday Times Review, Economist, and Independent as well as more radical titles such as the feminist Spare Rib and trade union magazines as well as books and displays. ‘We were documentary photographers, and [the idea of] Format Photography was to both support women photographers and try to make small changes to the way that various groups and issues were represented by the mainstream media,’ says Murray.

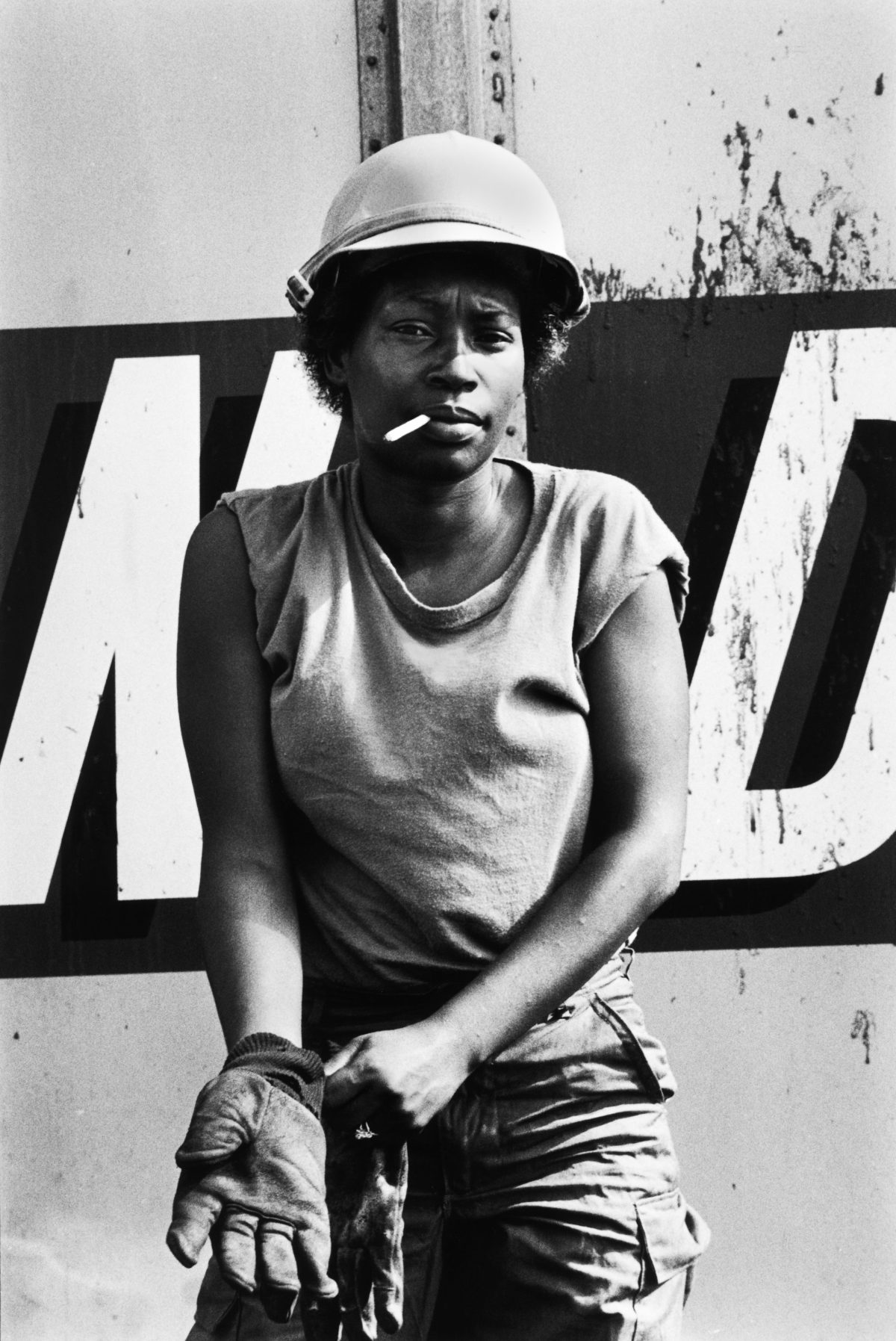

‘We played a very small part in a much bigger war, and often at a very, very small level,’ she adds. ‘For example, one very simple way was we would have as many photographs as possible of women doing non-traditional jobs. So when somebody approached us and asked for a photograph of a plumber, we would send them a woman plumber.’

‘There was an informal arrangement where you’d contribute to the [Format Photographers picture] library every month, and there was a list drawn up of things the office had been asked for and couldn’t supply,’ says Joanne O’Brien. ‘We were keen to change the narrative about visual representation. One of the running themes we were interested in was women, or disabled people, or people of colour, who were doing unusual jobs. Or another one was homeworking – now people work from home, but at the time that was very invisible. Any area of life that was relatively invisible was something we were interested in bringing to the floor.’

This ambition meant it made sense for the Format Photographers to pool their images, creating a resource for picture editors. But they also found other ways in which working together made them stronger, particularly when recording big events. One photographer couldn’t cover the sheer scale of the miner’s strike, they reasoned, so they photographed it as a group over its year-long duration; many of the Format Photographers wanted to go to Greenham Common, so they co-ordinated their coverage to do justice to its political significance. Working together also meant they could also share physical resources, as Jenny Matthews points out.

‘Raissa took a photograph of women dancing on a silo at Greenham [Raissa Page, who shot women dancing on a silo storing American cruise missiles at dawn on 01 January 1983],’ she explains. ‘It was Format that hired the 600mm lens, though I think Raissa was the only one who had the confidence or experience to use it. Certainly at night, the other lenses we had were too slow.’

Format Photographers gave practical support to its members, from ensuring the women greater bargaining power to giving them a forum to share technical knowledge and tips. Matthews had been involved with earlier collectives such as the Half Moon Photography Workshop, but it was Format that helped her get started as an image-maker, a career she’s now had for 40 years. O’Brien was in a similar position, and says Format helped her with ‘people who were more experienced sharing information’. But their words hint at another key aspect of Format, namely its moral support for women working in a male-dominated, sometimes misogynistic industry.

Shooting documentary photography can feel isolated, O’Brien points out, but shooting as a woman in the 1980s was even more so. ‘At the time, we were very unusual,’ she points out. ‘If you went to a public event or demo, you were usually one of a bunch of guys [shooting for the press]. You were always in minority, so it was nice having the solidarity [within Format], being able to share experiences, so that you could contend better with the sexism and misogyny you might encounter. I can remember guys laughing at my shoes, because I was wearing comfortable sandals to work in, or another time when one other woman showed up to shoot a national event, and a guy turned to me and said, ‘Wow there are a lot of woman photographers here’.’

Format Photographers had regular meetings to discuss both these experiences and photographic and business matters; all three women say how valuable these meetings were, though at the same time sometimes how painful. The photographers didn’t have to attend all of the meetings – Matthews, for example, was often away working on projects in South America – but when they did, the emphasis was on collective decisions. That meant issues such as how to take – and display – images of people experiencing homelessness were carefully considered, but it could also mean meetings lasted a very long time, and sometimes ‘sharing experiences’ tipped into airing grievances.

But Format’s longevity is testament to its value, both to members and its audience; when it eventually closed, it was down to the digitisation that saw off so many small agencies at the time. Unlike many other agencies though, Format didn’t see its archive swallowed up by one of the big picture libraries. Instead it was taken by the Bishopsgate Institute, an independent cultural venue in London that holds many collections relating to co-operatives, free-thinking, and protest, including the Stop the War coalition and the Lesbian and Gay News media Archive.

Format’s work and papers ended up there almost by chance, says Murray, because archives were something that ‘most of us working in the 1980s just never thought about’; fortunately an associate member of Format Photographers, Michael Ann Mullen, did think about it when Format closed in 2003, and urged Murray to get Format’s work into a national institution ‘or you’ll be forgotten in three years’.

Finding a home at Bishopsgate has helped ensure the archive is both preserved and accessible to picture researchers, historians, and curators, which is helping keep Format’s work in the public eye nearly half a century on. The curators from the Barbican looked through Format’s archive at Bishopsgate when preparing for the Re/Sisters show, for example; meanwhile publishing outfits such as Café Royal Books have reprinted some of Formats’ images, as well as publications by individual members Jenny Matthews and Brenda Prince.

Matthews, Murray and O’Brien are happy to see Format’s legacy live on, and say it’s gratifying to see their work on show in the big institutions – if at times a little dissonant. The Format Photographers didn’t necessarily themselves artists or their images art and, particularly when it came to the homeless, thought hard about whether it was appropriate to show their work in art galleries. Added to that, the people and topics they photographed were often not taken seriously, excluded or ridiculed in mainstream narratives. ‘If you talk to documentary photographers who were covering social issues of one sort or another at the time, people [who were protesting] were seen as outrageous,’ says O’Brien.

‘Look at the coverage of early the early gay and lesbian movement, they were seen absolutely crazy,’ she adds. ‘And the women who were protesting at Greenham Common, they were seen as completely mad. But given how right-wing the media is in this country, it’s not surprising how anybody protesting issues is considered. I mean look at the way Just Stop Oil are being represented nowadays, yet they have a really good point.’

Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990 is on show at Tate Britain until April. Re/Sisters – A Lens on Gender and Ecology is on show at the Barbican until 14 January. Find out more about Cafe Royal Books’ work with Format Photographers here. Jenny Matthews – Sewing Conflict is on show from 10 February until 05 May at Street Level Photoworks. Joanne O’Brien’s work is included in Look back to look forward: 50 Years of the Irish in Britain, a touring and online photographic and oral history exhibition.