As part of our Ideas Series, 'Girl on Girl' writer, Charlotte Jansen looks at women in photography using themselves and the female body to redefine gender roles.

In March this year, a 74 year old man called Carl Puia walked into his local Barnes & Noble bookstore in Connecticut and poured an unidentified red liquid over several copies of Kim Kardashian’s Selfish book – a collection of the star’s favourite selfies.

What do you see, when you see a photograph of a woman?

When women get in front of a camera, they face a whole history of photographic images in which women have been depicted to appeal to the heteronormative gaze, whether in the context of the mainstream media, art, advertising, porn or photojournalism. In the 1970s, women’s photographs of women were described as radical feminist, in the 1980s and 1990s, they were sidelined as satirical self-staging, and in the 2000s, early girl power aesthetics, hyperfeminine pop, reigned.

Since the introduction of the front-facing camera to phones in 2010, this time in women’s photographs of women has undoubtedly been shaped by selfies. For many people, a woman who takes a picture of herself is somehow connected to the idea of the Kardashian selfie. Where women do use their image to their advantage, in a world where women have been positioned to do so, they are ostracised for it. But in 2017, images of women demands to be seen with more nuance, in and out of the art world (as they inhabit all contexts at once). Petra Collins is just one complex example: an artist exhibiting at the MoMA, walking the Gucci catwalk, shooting magazine covers, photographing the growing pains of girlhood. Where she has been accepted into the art world, it seems very little of her art is being shown.

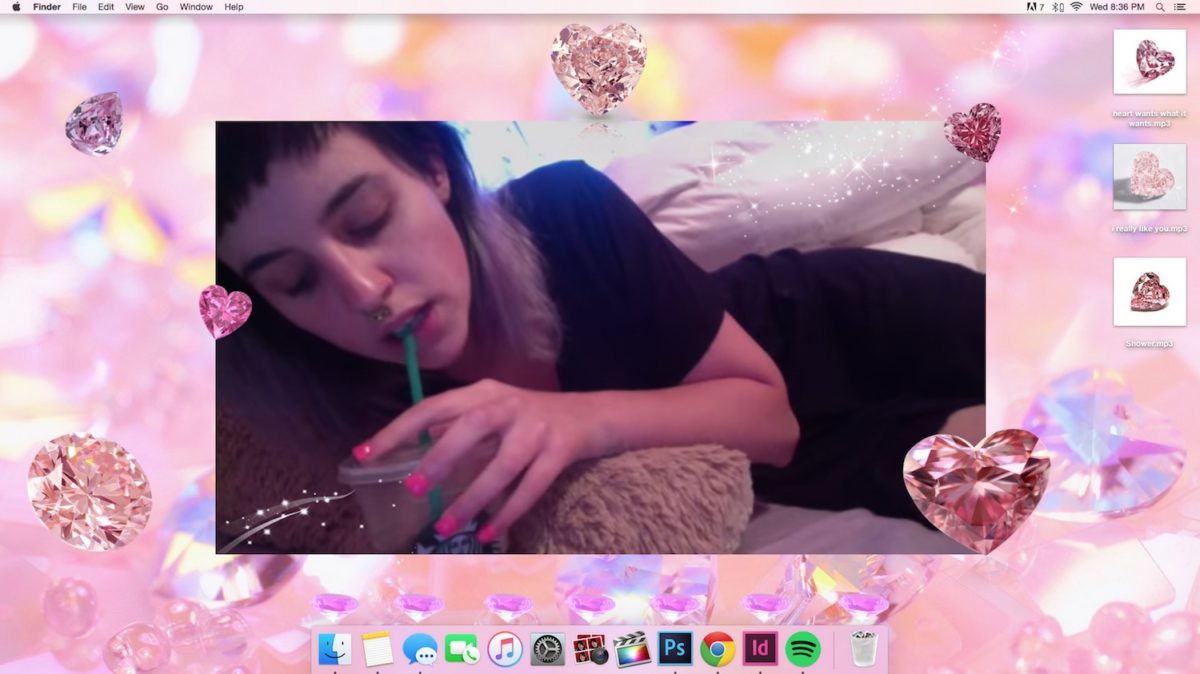

Photography struggled for the most part of a century to be recognised as an artform in its own right, but its persistent and prolific presence in our lives makes it the most effective, and most complex, influence on how we see the world. On the bus on the way to an art gallery or museum, we will see at least a dozen or more photographs of women, on our phones, on the sides of buses, in newspapers or magazine covers. It’s unlikely that whatever idea we get from all of those images -the Kardashian effect- can be separated from how we see a photograph of a woman in another context. Artists like Molly Soda and Alexandra Marzella artists whose practice is rooted in their bodies, in selfies, and in the Internet, have had to work very hard to be taken seriously, Marzella in particular has been slammed for pandering to the patriarch, as if the sex-positive 1970s never happened. Our perception of women’s photographic practices has yet to shift.

In the murky mundanity of Instagram, we scroll through all kinds of images of women, their messages blurred by their juxtaposition. The accumulation of these images gives us fixed ideas about how and why women photograph themselves. Isabelle Wenzel, for example, has never considered her spontaneous performances caught on camera to be a rumination on femininity, while Pinar Yolacan, who creates sculptures on her subjects’ bodies, doesn’t have a feminist motive, but rather looks at how we treat bodies, in images, in culture, and in their fleshly form. Female visibility is, in a sense, a fallacy: we see women in photographs everywhere, but the ideas we get from them are very limited.

For my book, Girl on Girl, I interviewed 40 female photographers who focus on photographing women, using either themselves, or other women, as their subjects. From their starting point, their experiences of themselves, and their vision of the world, depicted in their art, as unexpected, surprising, and varied, as life is in all the ways we live it. In their art, they live as equals, but in the world, their work isn’t treated equally. Many artists told me that they felt their work had been misunderstood or its meaning simplified. One photographer, Tokyo-based Monika Mogi, even told me of her surprise when she turned up to a shoot and she was expected to be the subject.

If contemporary visual culture gives us a narrow idea of women, a few tools to read photographs of women, then getting behind the lens as a woman brings with it its own challenges. In the past last five years, we’ve witnessed photographic phenomenon, of women shooting other women, either themselves or others, in ways we have never seen before.

Photography gives us power. Photographers such as Zanele Muholi, a visual activist who has dedicated the past decade to photographing her community of black trans and lesbian women in South Africa and its diaspora, don’t wait for things to change, they are using their cameras to intervene and create histories where there have been none. This is also the case in the work of Tonje Birkeland, who travels to remote locations, retracing the footsteps of forgotten female explorers, photographing herself in their place. For Lebohang Kganye, revisiting history is personal: going through family albums, she superimposes shots of herself dressed in her mother’s clothes, inhabiting her same poses, a way to come to terms with her grief and sense of loss; transforming time, rather than reflecting it. Women are creating, in photographs, the world they want to see, but it should not be understood as a world that is only exciting for women to live in.

I can’t say I haven’t ever felt the same urges as dear old Carl, to deface Kardashian’s photographed faces. Cultural and social conditioning is stronger than any notion of gender, race or sexuality. If only our photographs of women could be allowed to tell us everything they want to say.

Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze by Charlotte Jansen is published April 2017 by Laurence King Publishing RRP £19.99