From issue: #23 Seen/Unseen

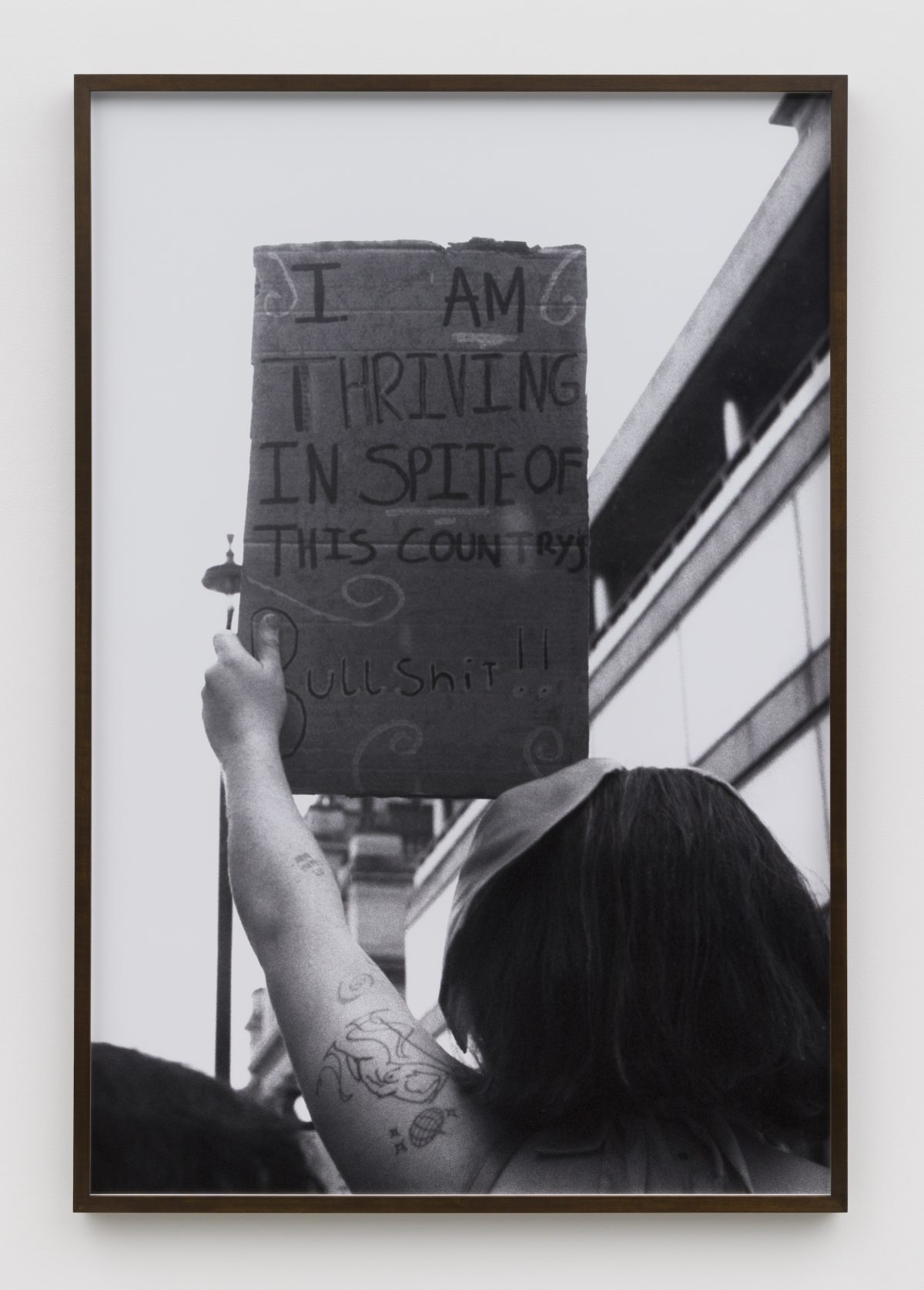

What responsibility does a photographer have towards the people they show? And are images fundamentally objectifying? Rene Matić is a London-based artist and writer whose practice spans photography, film, and sculpture, converging in a meeting place they describe as ‘rude(ness)’, or an evidencing and honouring of the in-between. Photoworks assistant curator Danit Ariel met with Matić to discuss their evolving approach to visibility; this is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Danit Ariel: You’ve recently articulated a need to pause in your practice, to reflect and return to questions about the camera’s place in unseen spaces – or whether the camera should be there at all.

Rene Matić: It’s an ongoing question that’s complicated and strange. At one point it felt important to bring the camera into unseen spaces, but as the work becomes more widely known, the gaze on the work expands too, and you end up inviting problematic…

DA: Seers?

RM: Exactly! And though it might not be my labour to consider who’s looking, it’s important to recognise that we need to constantly question the work because society is ever-evolving, and an image means different things at different times, and becomes more or less important.

DA: I’m curious to hear more on how an image changes over time, not only in terms of who’s gazing upon it.

RM: The best thing about an image is that it doesn’t change over time, but what happens around it does. That’s something I’ve always been extremely excited about – the image almost watches the world more than we watch it.

DA: The world changes and the people change. I think many photographers find that if they are depicting a person and desperately trying not to objectify them, perhaps particularly in relation to queer people, that there needs to be an ongoing negotiation around whether an image is still relevant or should be used.

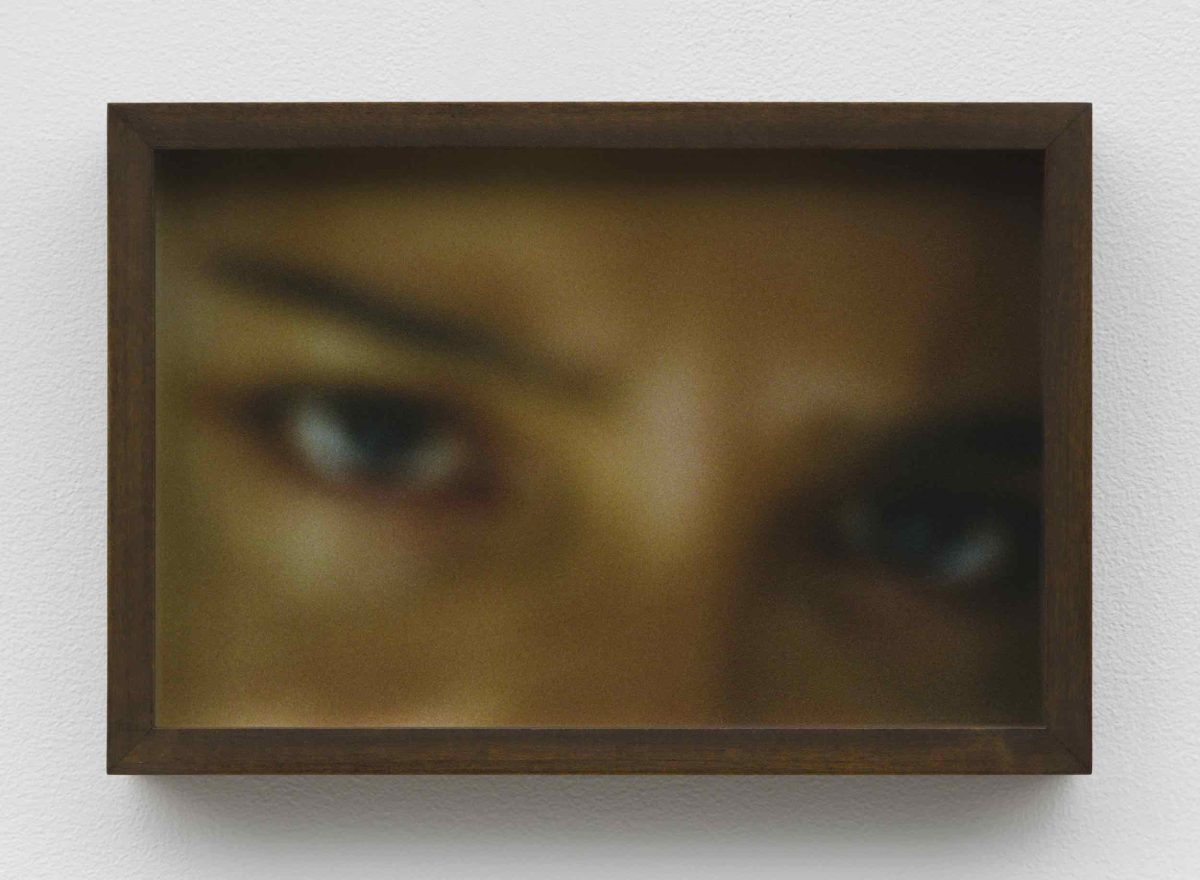

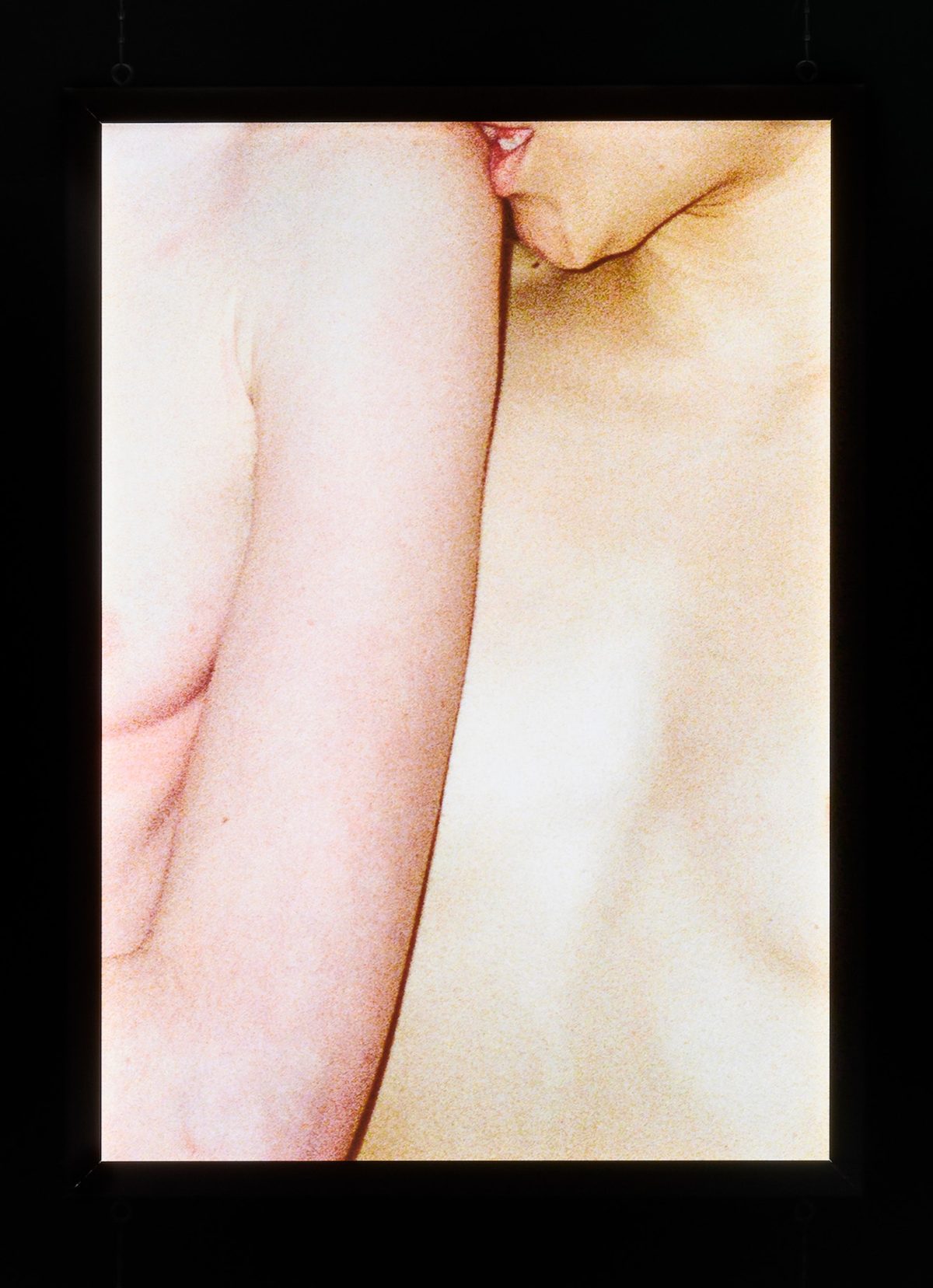

RM: Yes, does this person want to be immortalised in this way? I’m confused about this myself, but I’ve made new work for a show in Vienna, and I always want to preface any work I make by saying it’s always a questioning and a figuring out whether this is the way to go about it. It might not be, so I’ll go back to the drawing board. But the images I’ve done are in between seen and unseen, there is a blurring, a movement, or bodies that are not in their entirety. And I wonder whether that’s okay, because if you don’t give a body a face, that really does objectify, even if it distances the work from the initial problems that we have with depicting identity markers.

DA: Definitely! But I think that it’s about the thinking and the constant reflection on one’s work. Embodied practices move with their makers, and you don’t have to get to a bottom line or destination or absolute truth. Maybe those linear and result-based pathways are what can be restrictive or even violent, so I’m definitely very excited to see this new experimentation.

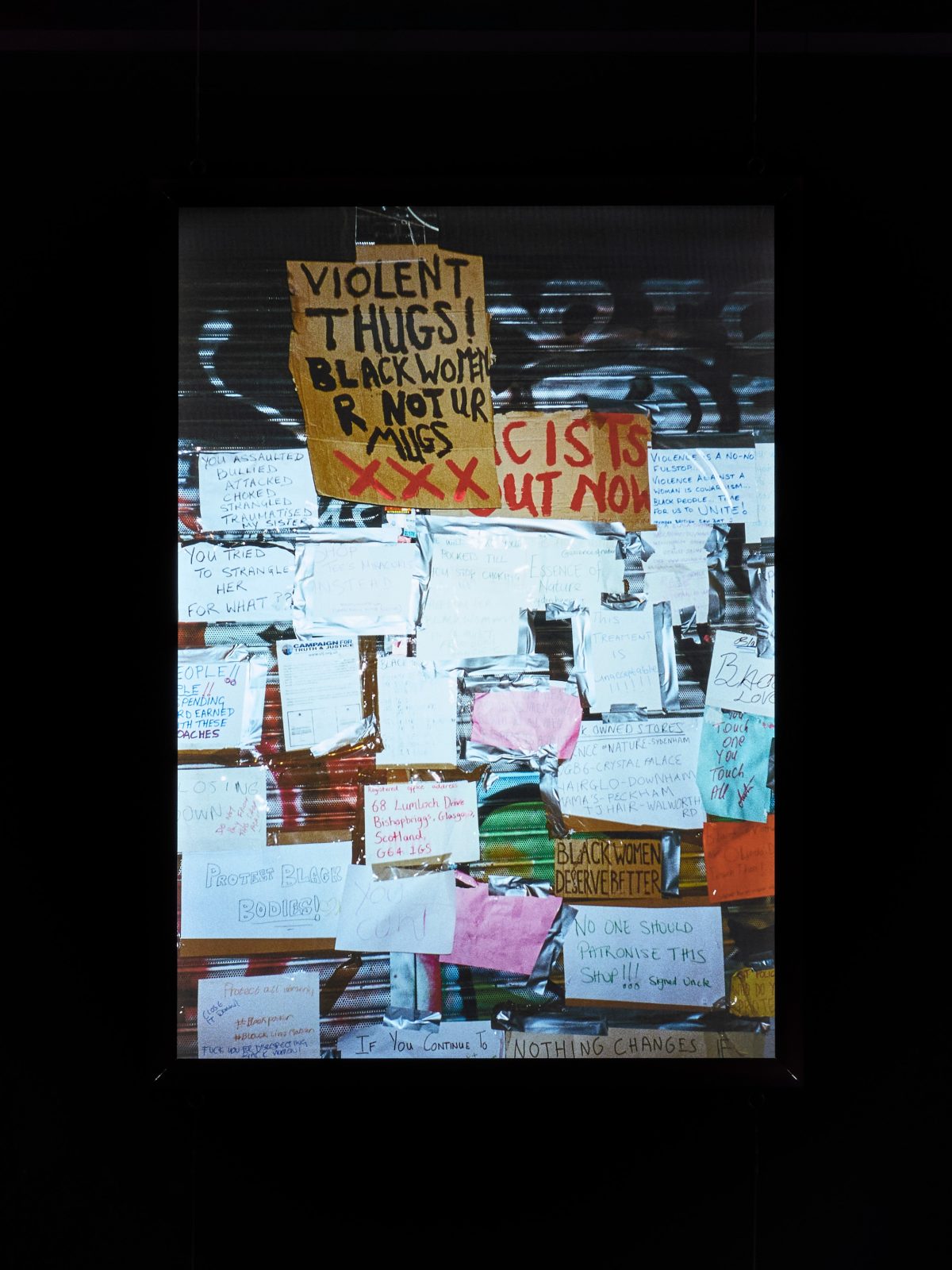

RM: They’re lightboxes and I’ve never done that before, which is cool. I’ve thought long and hard, less about what’s in the image and more about the image as a surface. I’m always about intimacy, looking at relationships, and my relationships with the people in the images, and this work is more about the intimacy of the image itself, in the cropping, and the zooming in. We’ll see what that does, especially when it has light behind it. They’re all 35mm so there will be stark grain, it might end up looking like data. I’ve had the pleasure of reading Legacy Russell’s Black Meme where she writes in favour of the poor image, which I’ve found helpful in thinking about what to do next with my practice. Is the distortion of the image the way to go? To have something both seen and unseen in that moment, all at once.

DA: I definitely think grain, and obvious cropping, methodologies that remind people that this is an image rather than the person in the image, really do disrupt this notion of seen and unseen, because the viewer becomes much more aware of the act of seeing.

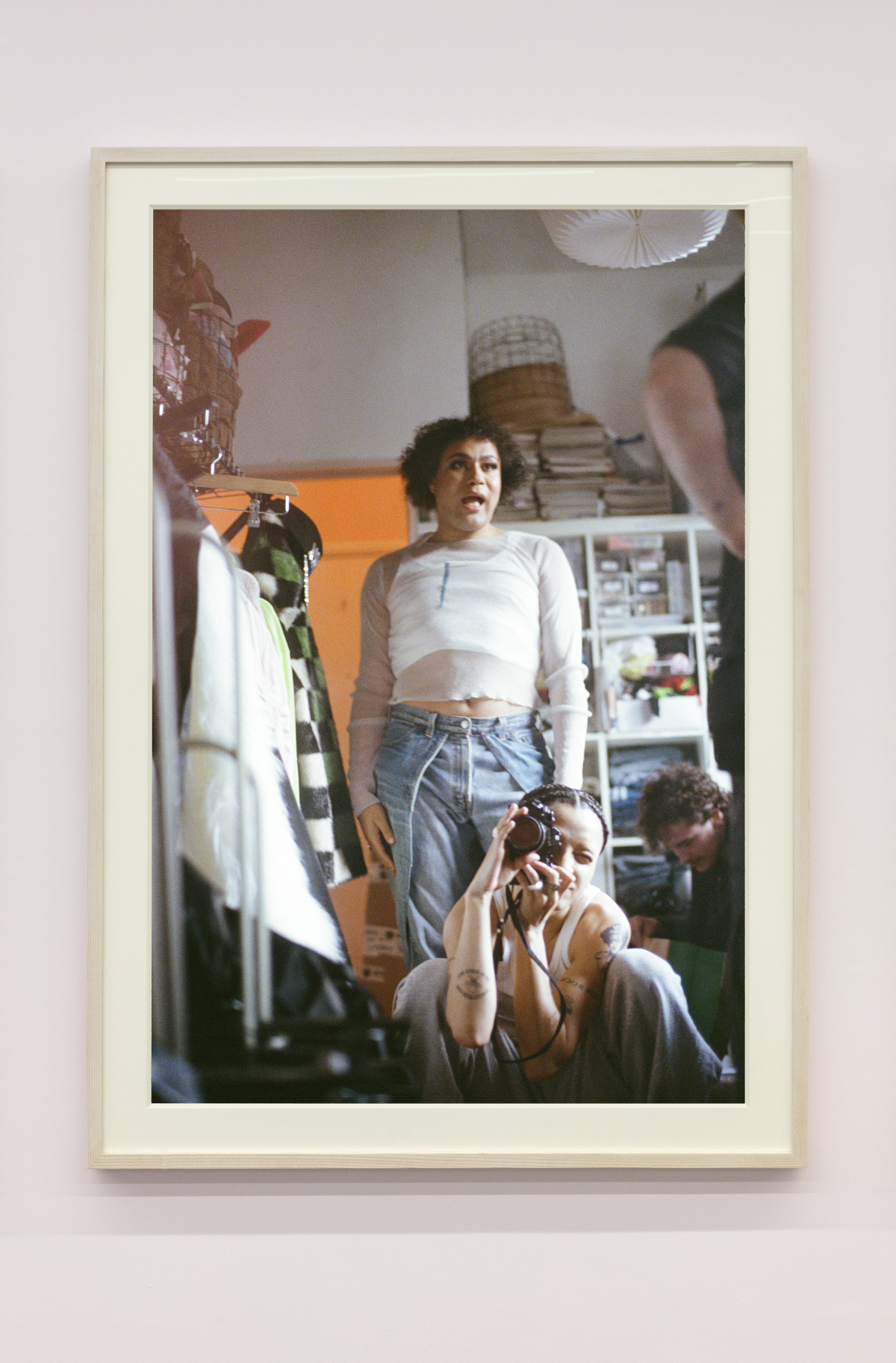

RM: It makes the encountering more obvious, and that feels like adding another layer of protection for the people in the images; it compromises aesthetic but that’s a fair compromise. I think that a lot of the photographers that I admire have not thought about consent in that way. For me it’s a priority, which is why I only photograph people I know and love, because we can always speak about the images again. I closed the chapter of Flags For Countries That Don’t Exist But Bodies That Do to figure out how to give more privacy back to these worlds that deserve and need it – though these worlds are already unseen, which is why I picked up a camera in the first place.

DA: Most people don’t change something that’s working, so the fact that you’re making space to question your practice is admirable. I’ve been excited to see where you take your practice because making the unseen seen is where a lot of the rudeness comes into play, and it sounds like you’re coming up with new ways to be intentionally disobedient.

RM: Absolutely. I’m recognising that in this moment, the pause and the withholding is the rudeness. My practice became quite clear, the audience is happy, and I don’t like that. It’s amazing to be up in the Tate, but what does that really mean? It’s not easy because I love making that work, but I want to keep something back for us, and for my work to keep its secrets. It becomes more confusing when I think about a girl for the living room, my friend Travis Alabanza [featured in it] loves being in front of the camera.

DA: That work encapsulates the beauty of being seen by a loved one.

RM: And who am I to take that away? I suppose it comes down to conversations with every imaged person, and those conversations are the most blessed part of this work.

DA: How do people experience the intimacy in your work? I find the tenderness to be another rudeness and resistance in a world that lacks those safeties. But the paradigm we live in positions tenderness and rudeness as opposing forces.

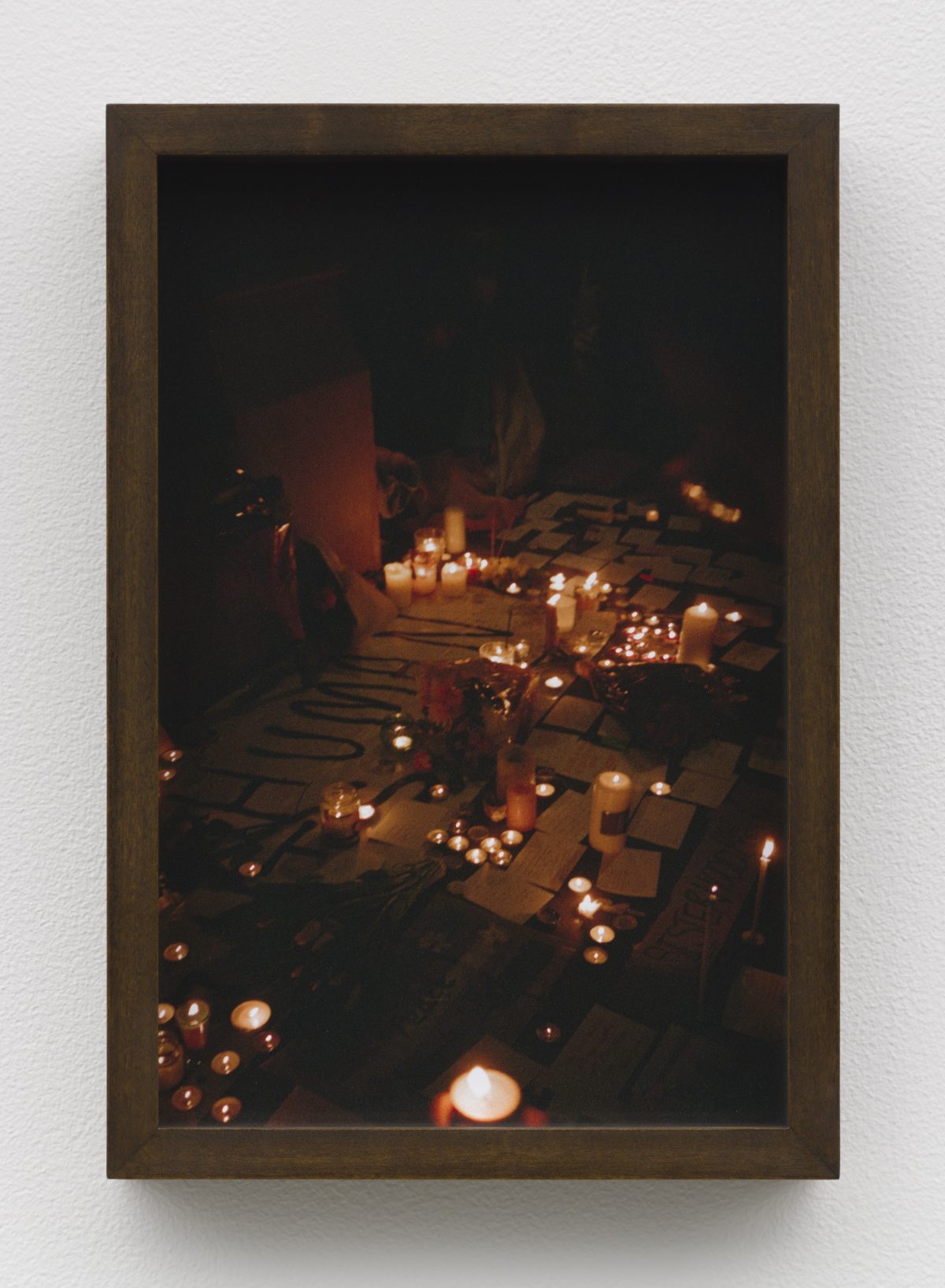

RM: I’m an angry person, I think anger is important, but I can’t survive in this world with anger leading me. I slowly and painfully recognised that I need to translate that anger and what I always come to is love. Which is simple. Well, I say simple but love is complex. But I always urge an audience to remember that it was me looking first and that’s me asking people to remember that there was a moment of love, even if it’s a picture of a Union Jack. In the new work I’m showing quiet, intimate moments without the defining characteristics of people or symbols of identity politics. The identities become the protected secret and the tenderness is brought to the forefront. That’s what I’m interested in now, especially when there’s a huge desperation for tenderness.

DA: I really relate to that. What is missing right now is a diversity of approaches to being together in this world.

RM: Yes, the question is what is missing in this moment – that is the rudeness. Maybe it’s not about withholding, it’s recognising what is being withheld from us.