From issue: #23 Seen/Unseen

Photographs taken in secret by cross-dressers in the 1950s and 60 are now being widely published and shown: curator and editor Isabelle Bonnet has pondered the ethics for and against showing their images, finds Diane Smyth.

In 2004, Robert Swope and Michel Hurst found a cache of photographs in a New York flea market. Including one hundred loose snapshots and three photo albums, the collection had once belonged to Susanna Valenti, a key figure in the cross-dressing community in the 1950s and 60s US who ran the Casa Susanna with her wife, Marie – a place in the country in which members of the community could meet as their best female selves. Swope and Hurst published a book shortly after finding the images, and it inspired a musical in 2014 and, in the same year, the Camp Camelia setting in an episode of Transparent.

In 2005, the artist Cindy Sherman discovered 214 more photographs previously owned by Susanna, and in 2013 she exhibited them as part of a group show within Massimiliano Gioni’s The Encyclopaedic Palace at the Venice Biennale. Since then several other image collections relating to Susanna and her circle have come to light, and a documentary, called Casa Susanna, has been released [it came out in 2022]. An exhibition of this wider collection, also called Casa Susanna, was shown at Les Rencontres d’Arles in 2023, and an accompanying book published by Thames and Hudson.

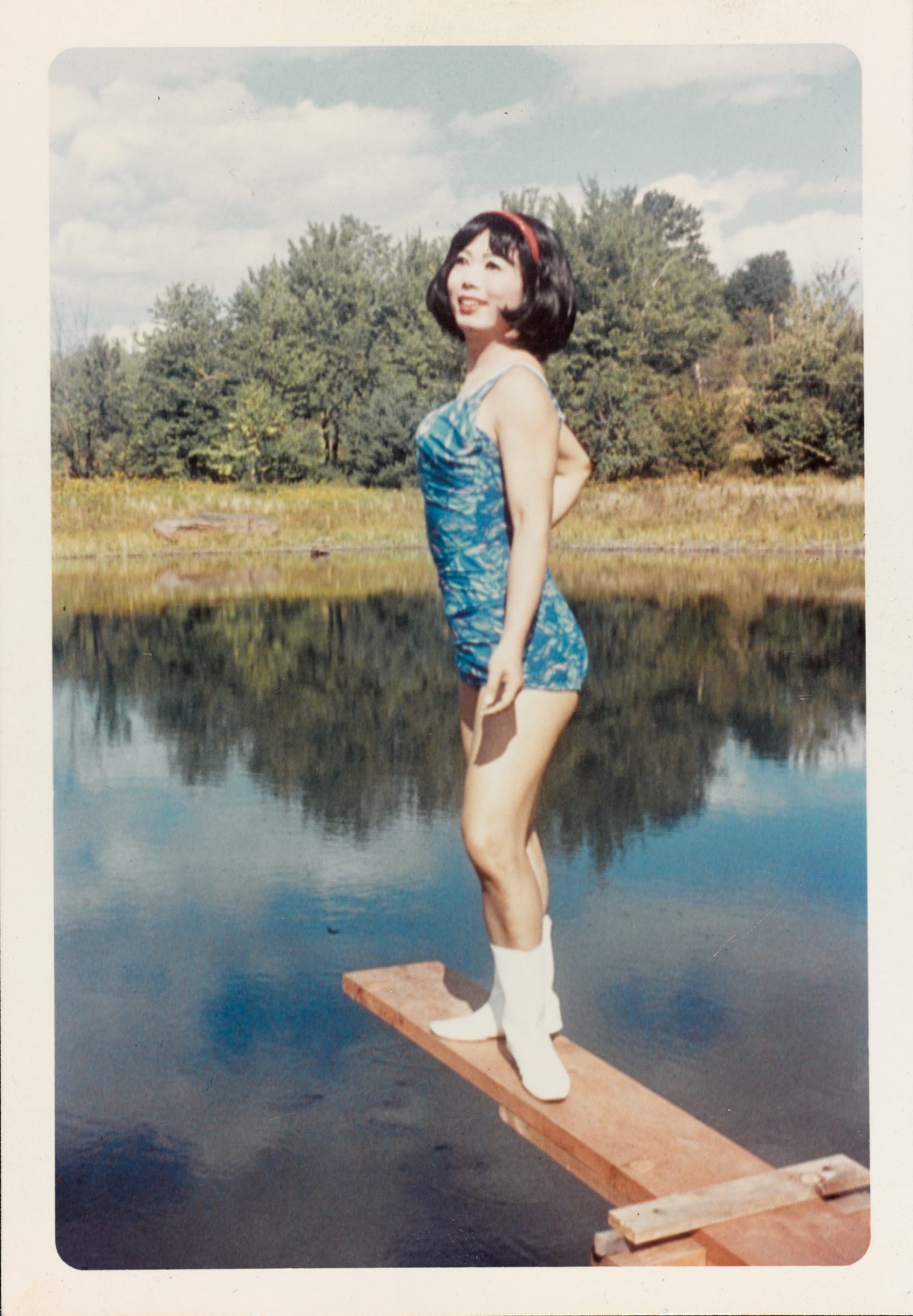

The contemporary interest in these images is born of a wider acceptance of, and interest in explorations of gender and its expression. But this interest also poses a dilemma. The images shot at Casa Susanna and beyond were shot in private, sometimes with the curtains literally drawn; the women who took them learned to develop these shots or used Polaroid to avoid photo labs. Questioning gender norms was discouraged in the postwar America, and doing so could provoke police investigation and even arrest. Those who sent images of cross-dressing through the post could be arrested, for example, for ‘distributing obscenity through the US mail’.

Susanna had a column in a magazine, Transvestia, and photographs of the cross-dressers, transvestites, and others in her community were published in it, along with first-person accounts and ads. But Transvestia was distributed to a small circle of subscribers and via a select few newsstands, and the anonymity of its models was assured. Referred to by their female names only, these individuals weren’t linked with identities elsewhere in life, and the same was true when they met in person. Visitors at Casa Susanna and beyond were actively discouraged from sharing their birth names and addresses for example; when they died, close friends were sometimes tasked with clearing their homes of all trace of their womanhood.

Privacy issues

The boundaries between public and private were closely guarded by these individuals, that’s to say, so what are the ethics of openly publishing and showing their images now? It’s a question Isabelle Bonnet has asked herself, although – co-curator of the Arles exhibition and co-editor of the accompanying book – she has written about Susanna’s biography and revealed the identities of several fellow travellers. Bonnet’s essay in Casa Susanna details that Susanna was born Tito [Humberto] Arriagada in Santiago, Chile in 1917, for example, and that Virginia Prince, editor of Transvestia, was also known as Charles; Bonnet writes that the ‘New York gang’ included Felicity, aka John Miller, ‘the brother of the photographer Lee Miller…an airline pilot, aviation pioneer, and World War II hero’.

These details are the result of Bonnet’s meticulous research into Casa Susanna and its visitors; a photo historian, Bonnet has tracked down many of those involved in the scene, and spoken with them or their families. Even so, she says, ‘I didn’t want to find all the people, because I know that some of them don’t want to be found’. The secrecy which surrounded the Casa Susanna persists for some to this day. On the other hand, as she points out, for others it barely existed – even at the time and in their lives.

Her essay picks out the six-foot Felicity’s love of bamboozling police officers, for example, by asking them to photograph her to show ‘her girlfriends when she gets back to Texas’. ‘Some of them were not hiding their cross dressing during their life, and that was a green light to find their names,’ she says. ‘It was a mixture. But I never, ever gave the name of someone I was not sure would want to be identified.’

As Bonnet adds, many of those in Susanna’s circle must now be dead and so, if they kept their female identity a secret, this secret has now died with them, or has already been revealed. If the former, she reasons, it’s unlikely the photographs alone will out them. She hasn’t seen any images of Susanna as a man, for example, and says she can’t imagine how Susanna would have looked in male attire. Other women at Casa Susanna are similarly hard to envisage otherwise.

Freedom of expression

In fact, these individuals inhabit their female identities so thoroughly it suggests another intriguing question, Bonnet points out – whether they would have still wanted to keep their cross-dressing secret now. Half a century ago, it was dangerous to be open except in a few special cases; perhaps now, in more tolerant times, they would relish being able to express themselves. ‘Back then they couldn’t afford to lose everything,’ Bonnet muses. ‘But that’s why Casa Susanna was so incredible, because there they had a kind of freedom.’

And, as the huge image cache suggests, photographically speaking, these women very actively showed and recorded themselves. Photographs from Casa Susanna show tables covered in Polaroids and several women wielding cameras at each other; images from Susanna’s New York apartment show women shot in front of a floor-to-ceiling mirror, their bodies and outfits captured head-to-toe from two different angles. ‘Photography was an obsession,’ Bonnet observes, ‘because they were the only proof of the existence of the women that they were.’

It’s a poignant insight into lives kept hidden from wider society but celebrated in their own communities; as such, argues Bonnet, these images suggest much bigger questions around which histories are seen and remembered, and which ones marginalised and forgotten. As a photo historian, she sees these photographs in terms of a wider project in which LGBTI+ stories are reintegrated into our history – partly to give this community back its own history, but also to ensure wider society realises it’s always existed.

‘One of the women I spoke with said she felt it was important to show herself now, to be a witness to her own life,’ Bonnet explains. ‘The extreme right is rising, and with it people trying to argue that questioning gender is just a fashion. But these images show that it isn’t new and also isn’t a fashion. Even when it was so dangerous, there were people who just had to do it.’

Casa Susanna The Story of the First Trans Network in the United States, 1959-1968 is edited by Isabelle Bonnet, Sophie Hackett and Susan Stryker and published by Thames and Hudson.

Book Giveaway! For a chance to win 1 of 3 copies of Casa Susanna head over to our Instagram. Giveaway starts 2 April and ends 7 April at 5PM. Open to UK residents.