In the lead up to the launch of Matthew Finn's publication 'Mother' this week at Rencontres d’Arles, we spoke to publisher Dewi Lewis about this latest publication, his career and what for him makes a great photobook.

Photoworks: Can you tell us about your move from running Manchester’s Cornerhouse arts centre to setting up Dewi Lewis Publishing in 1994? What led you to focus on photography and the photo book?

Dewi Lewis: I began working on setting up Cornerhouse in the early 1980’s and we opened to the public in 1985. We had 3 gallery spaces, 3 cinemas, education facilities, a bookshop, a bar and a cafe – my job was as Director of the Centre. I already had an interest and enthusiasm for photography but in conversation with various photographers I began to realise how important the photo book was and how few opportunities there were for publication, particularly in the UK. And so I began to research the possibility of setting up a publishing imprint in Cornerhouse. I managed to get some support, both moral and financial, from Barry Lane who was Photography Officer at The Arts Council at the time and in 1987 we launched the imprint with ‘A Green and Pleasant Land’ by John Davies. Fortunately it was successful enough for us to get back the funds that we had put in and I was able to persuade my Board that publishing was both a viable and appropriate way for us to work.

Over the next seven years we managed to publish a host of great books working with people such as Martin Parr, Paul Graham, Bruce Gilden, Peter Fraser, Paul Reas, Tom Wood, Susan Lipper and many others. We also worked with other publishers such as Aperture in the States and Scalo in Germany on co-editions with photographers including Nan Goldin, Elliot Erwitt, and Nick Waplington. We even published the first UK edition of Robert Frank’s ‘The Americans’.

My problem was that it was already a full time job running Cornerhouse, which was a seven day a week operation employing close to 100 full and part-time staff. Consequently, as the publishing side developed my work load grew even more – and I got increasingly frustrated that I couldn’t spend as much time as I wanted on the publishing side. I took the decision to leave Cornerhouse and establish my own publishing house, and so in June 1994 I started my own imprint.

Photography was always the key focus – not least because it was what I had been concentrating on for the previous seven years – although after a couple of years we did also begin to publish fiction – essentially new fiction. There are complex reasons for why this came about but certainly one of them was that my degree had been in English and I felt comfortable working with text. Sadly, the fiction list lasted only a few years – we had excellent critical success – getting on the Booker Prize shortlist one year and on the long list on another, as well as winning other awards – but very little commercial success. And then there came a big shift in how the main bookshops operated, and how responsive they were to new fiction. It was a hard decision but we had to stop and once again, our focus moved back almost exclusively to photography.

PW: What are the current challenges/opportunities in photobook publishing? How do you think they differ from the photography landscape of the nineties?

DL: These days people talk of a golden age of the photo book. This is in part true – certainly the number of people interested has expanded, the market has increased – but there are a lot more books out there, in reality far too many for the number of potential buyers. What it ultimately means is that more and more books need some form of external financial support. At the moment I would say that we fund around 65% to 70% of the costs of our books – but that is rather a misleading figure in that some projects we fund 100% and others perhaps 15-20% of the costs. But the hard fact is that whilst we used to fund many projects by emerging photographers, we can simply no longer take that sort of financial risk.

The publishing world is entirely different from when I first began in the late 1980’s. Then, the bookshops actually bought books – these days it is all sale or return. Then, trade discounts would run at around 30%, now they are averaging closer to 50%. And so the financial risk for a publisher is much greater and the money that you can get back much less.

On the plus side, photographers can now publish their own books much more easily – and there is a much greater and more accessible pool of knowledge about the issues of production and design. They can also produce relatively low cost digitally printed ‘booklets’ and fanzines.

What does worry me though, is the continual need for photographers to find money to get their work into the public arena. For me this can only create an imbalance which over time will become elitist and undemocratic. Will we only see the work of mid career photographers and artists who have their own private funds to get their work out there? To be an artist will you need to be a Trust Fund kid?

PW: What for you makes a good photobook/photograph?

DL: For me it always has to start from content. Only then can you move on to considering form. In the end a great book is the perfect balance between content and form.

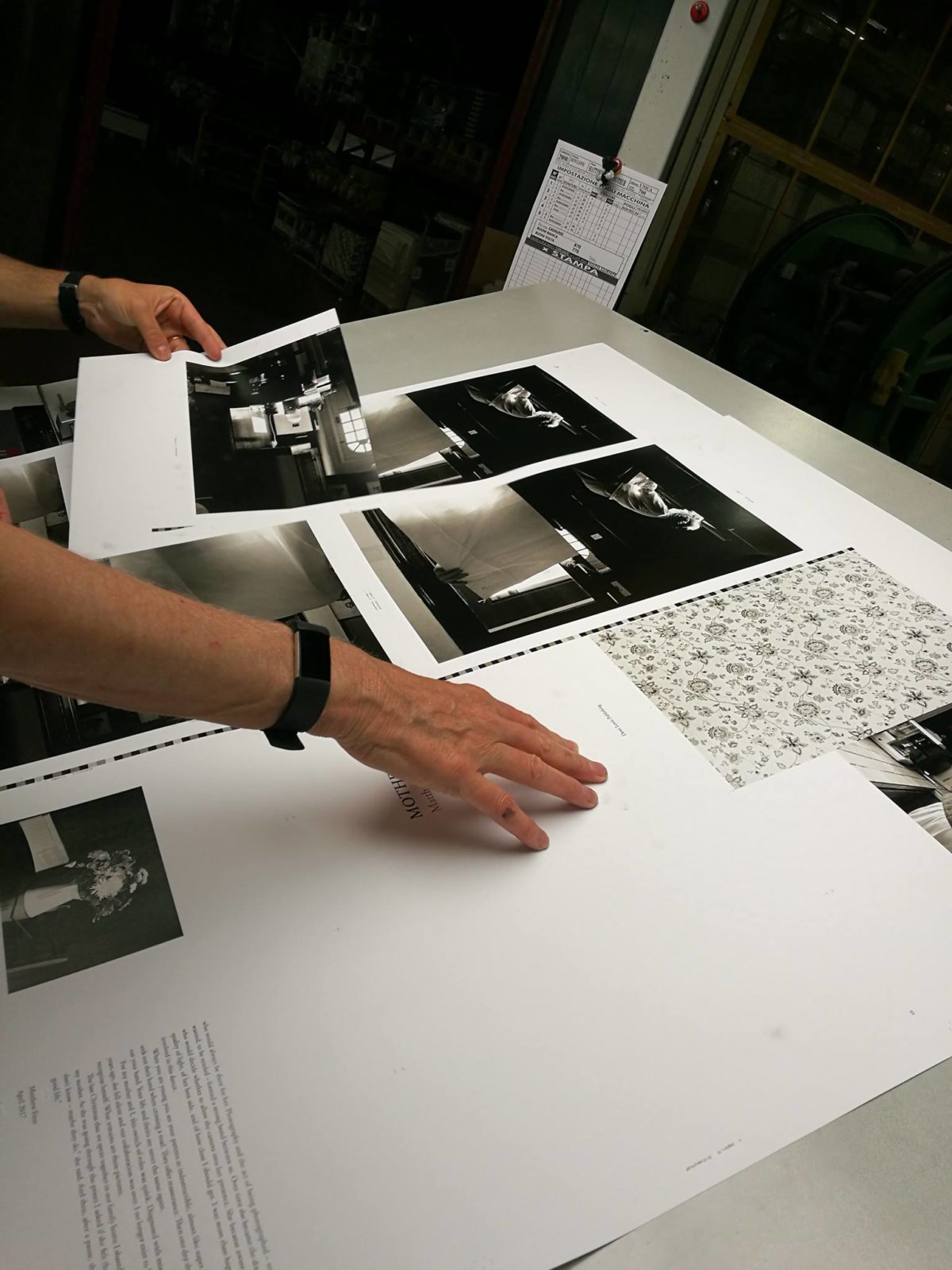

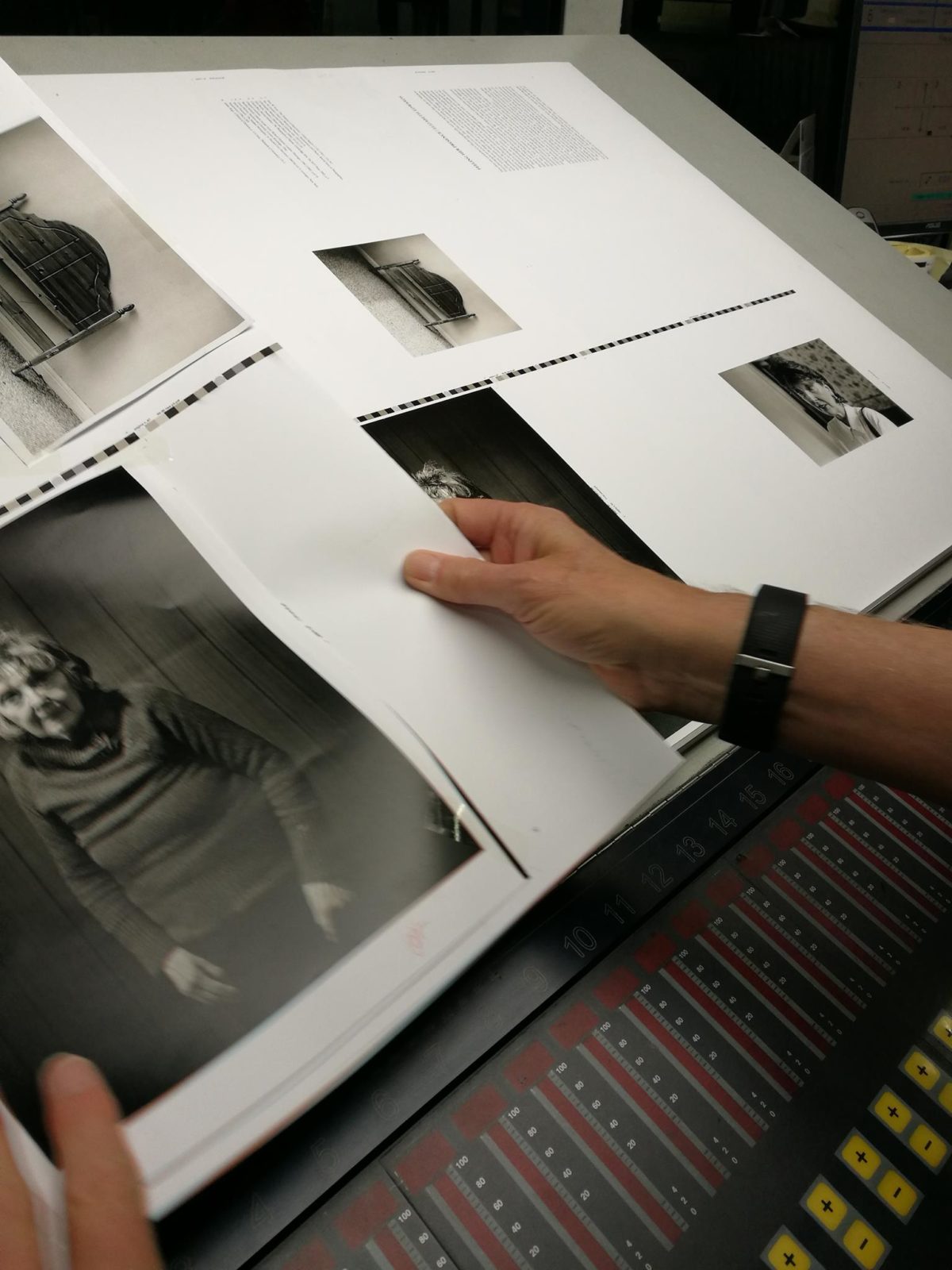

Ultimately there are a several key things that make a good photo book – the photographer has something to say and has found the way to say it, the input of the designer is a truly collaborative one, any text is there because of what it adds and not because of the writer’s reputation, the production is in keeping with the nature of the project etc.

Essentially everything in the book has a job to do – to present the work of the photographer in the strongest possible way.

PW: With the launch of Matthew Finn’s first publication through Dewi Lewis, what initially attracted you to Matthew’s work?

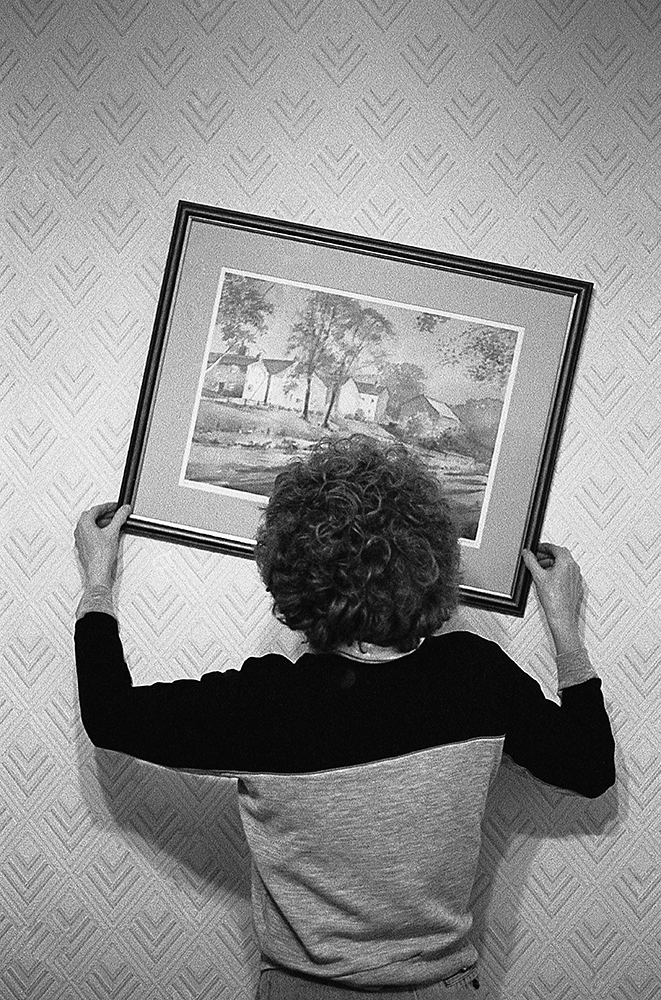

DL: I would have to say that it was the obsessive nature of the work. That level of commitment is something that I always find myself drawn to. But, of course, obsession by itself is not enough, there always needs to be a quality of vision. It seemed to me that in the process of photographing this one person time after time, Matthew has found a way to use the camera to properly see his mother.

PW: Can you speak a little about the process of creating a photobook like Matthew’s? Do photographers approach you with finished dummies or is it a collaboration from start to finish?

DL: Every year we get several hundreds, if not thousands of submissions. Alongside that, I also actively look for work – in magazines, online, at exhibitions and at portfolio sessions. Out of all of those I see, we’re able to publish around 20 each year. Very occasionally – perhaps every three or four years – a photographer will come along with a dummy which is more or less ready to run with. Even then though it will almost always need some adjustments in sequence or form for me to feel I can commit to it. For everything else there is a process of developing the project and moulding it into a form that does it justice.

PW: Matthew’s most recent work was created through his inclusion in the Jerwood/Photoworks Awards. The three winners’ work toured as an exhibition throughout 2016 and Matthew’s presentation developed to include wallpapers reminiscent of his mothers house. What can we expect from the publication? How does the book vary from the exhibition?

DL: I’m a little embarrassed to say that I wasn’t able to catch the exhibition. Perhaps that’s a good thing in that it meant when I began to work on the editing process for the book, I wasn’t burdened with any preconceptions about how it should look or feel. Matthew provided me with a selection of close to 300 images and I worked from that, slowly building a selection which seemed to me to create a flow to carry the reader through the book.

For me, one of the strangest things of working on an edit of images such as these, is the relationship that you develop with the people featured in the work. It would be wrong to suggest that you begin to know them in any way, but it is certainly true that you build a connection. Invariably, I begin to feel protective towards them and very conscious of how I am presenting them – I begin to feel that I have a responsibility towards them. I’ve felt this on other similar projects such as Elin Høyland’s The Brothers or her book Brother / Sister.

PW: What do you hope the book will achieve?

DL: I hope that it will fairly represent Matthew’s mother to Matthew and to those who view the work without knowing either him or his mother.

PW: What’s next for you?

DL: More books, more excitements, more frustrations.

For more on our Ideas Series, click here.