From issue: #18 Science Fiction

Text by Diane Smyth, Photoworks

Born in Sheffield in 1987, Johny Pitts is a self-taught photographer, writer, and broadcaster. The founder of the online journal Afropean.com and author of Afropean: Notes from Black Europe, Pitts spent more than a decade documenting the Black experience in Europe, amassing an archive of over 100,000 images. A selection of this work was exhibited in Pitts’ first solo show, held at Foam in Amsterdam in 2020.

In 2021, Pitts won the inaugural Ampersand/Photoworks Fellowship. An open-call opportunity for mid-career artists, this Fellowship aimed to help one winner complete and exhibit a new body of work, though support including a £15,000 award, mentoring and curatorial help, a production budget, and touring exhibition. Pitts worked on a project reflecting on Black Britishness, starting in London, journeying along the Thames, and circumnavigating the British coast.

Home Is Not A Place went on show at Graves Gallery, Sheffield on 11 August-24 December 2022, and opens at Stills Gallery on 23 March 2023. HarperCollins UK published book of the same name in September 2022, made with poet Roger Robinson. Pitts’ work is also included in the Photoworks Festival 2022.

About halfway through the book Home Is Not A Place(2022) there’s a photograph taken from inside a car, looking out through a rainy windscreen at a stretch of water and cliffs, a battered British road map on the dashboard. It’s a useful image to sum up the book, a collaboration between photographer Johny Pitts and poet Roger Robinson that takes the form of a road trip down the Thames and around the British coast. This image is also interesting because it’s so familiar, a view that pretty much anyone in Britain will have seen, but whose interpretation can vary widely from community to community.

Towards the end of the book is a text by Robinson titled The Sea Means Something Different to Us, which references a JMW Turner painting once named Slavers throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhon coming on, a Nigerian church baptism on Margate beach, and an anti-racism protest overlooking the same coast. Margate was once the headquarters for the right-wing UK Independence Party and a hotbed of the far-right British National Party; it’s now home to an activist called Kelly Abbot, co-founder of the People Dem Collective which organised the protest Robinson describes. ‘She tells me that every day her ancestors speak to her from the sea, that the sea holds all Black people’s history from all times and if you listen and look hard enough you can feel them there,’ Robinson writes.

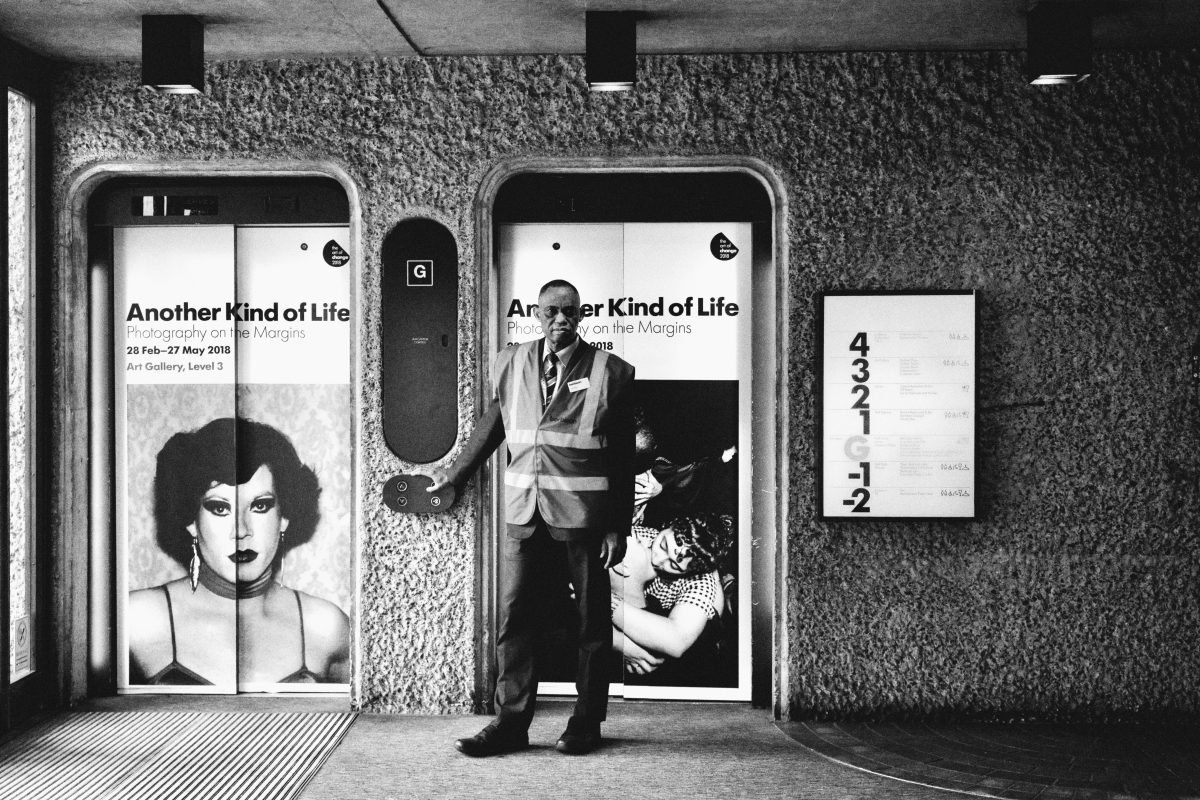

Home Is Not A Place is specifically road trip ‘towards a Black psychogeography’, as Pitts puts it, which tries to look beyond British stereotypes and reveal an alternative perspective. Pitts was partly inspired by the ephemerality of the fabric of Black and working-class lives, by the urge to capture places that are often redeveloped or privatised or plain razed right out of existence. He was also inspired by updating and undercutting icons of Britain, by showing that police officers and London Guards aren’t always white. ‘I’m playing around with what people expect from Britain,’ Pitts tells me. ‘I’m playing around with these national cliches, trying to subvert them by showing other groups that are a part of it.’

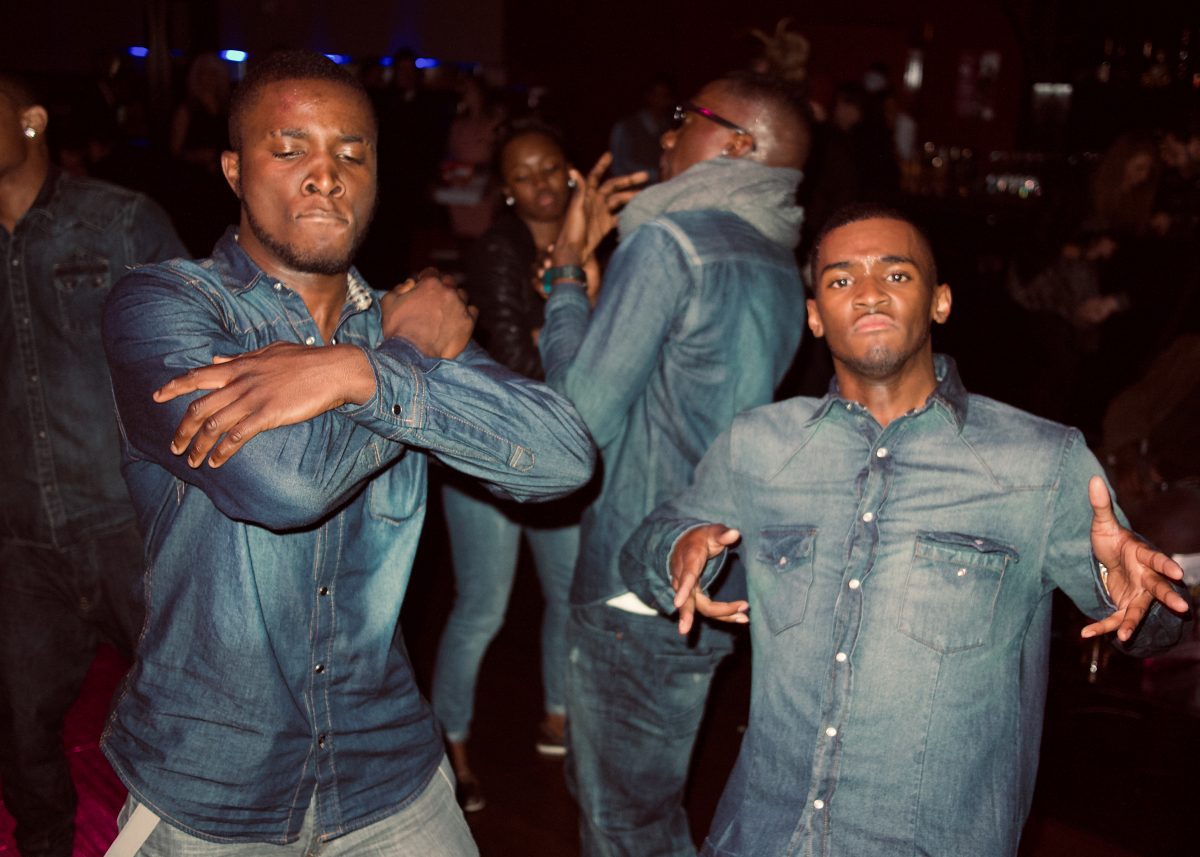

Pitts also hopes to expand the narrow representations of Black British life, what he’s called the ‘Brixtonisation’ of a broad set of experiences. His images include shots of Yale University professors, best-selling authors, and lord mayors, but he’s deliberately avoided the ‘noble hero portraits of famous black people in Britain’. He’s also avoided the dramatic. Instead, he offers something much quieter. ‘Often, when we see images of Black people, it’s images of protests and it’s all very anxiety-inducing,’ Pitts explains. ‘When I see so much photography, even from Black photographers sometimes, it’s like, “Oh God everything is shit!”

‘With this book,’ he continues, ‘even though hopefully it’s not oblivious and there are some haunting images, I wanted it to be more meditative. I wanted people to be able to just sit down with it with a cup of tea, to take a moment out.’

Born in Sheffield, North England in the 1980s, Pitts has first-hand experience of a richly multicultural Britain. He grew up in Firth Park, an area that was home to well-established communities from Yemen, Jamaica, Pakistan, and India, as well as white working class people. Later it also became home to economic migrants and refugees from Syria, Albania, Kosovo, and Somalia. Firth Park was no utopia in the conventional sense but it was alive and convivial, built on the tolerant atmosphere that comes of sharing space with diverse cultures. ‘Firth Park was anything but boring,’ Pitts writes in his award-winning book Afropean. ‘It was rough, but it was full of culture and community spirit.’

Pitts’ home was a rich mix too. His mother is from a white working-class family with Irish roots and his father was an African American musician from Brooklyn, who first came to the UK with his band, The Fantastics. The couple met on the Northern Soul scene, the music and dance phenomenon that exploded in Britain in the 1960s when white working-class communities adopted the power and passion of Black American Soul. Pitts’ home life was warm, open-minded, and cultured but he faced challenges growing up working-class and Black in Britain. Some of his friends took a wrong turn, and Pitts says there were times he could easily have done so too.

The 2008 financial crash and its fallout only exacerbated the problems. Soon afterwards the Conservative government created its ‘hostile environment’ for immigrants and orchestrated the Windrush Scandal, deporting hundreds of commonwealth citizens, who often hadn’t been ‘home’ since they were children. Pitts headed for Europe by way of escape, first on a five-month road trip in search of the Black European experience, a journey which formed the basis for Afropean. He then lived in Marseilles for a spell, attracted by the city’s multicultural life. ‘Marseilles is a melting pot,’ he says. ‘When I was there I was drawing parallels between Marseilles and home, joking that it’s Firth Park by Sea.’

But despite its hardening political environment, somehow Britain did remain “home”. When Covid hit, Pitts and his family moved back to his mother’s house in Sheffield, because she has a garden and because ‘you know, we’d spend it together’. ‘I realised my roots are still here, frustratingly,’ he says. ‘I fell out of love with Britain but, when everything hits the fan, my community here.’ He was reminded of James Baldwin’s novel Giovanni’s Room, of the idea that ‘Perhaps home is not a place but simply an irrevocable condition’. His series Home Is Not A Place, which was supported by Photoworks and has been exhibited as a solo show, was partly an attempt to make sense of this seemingly irrevocable tie to Britain. It was also an attempt carve out his place in it.

That’s something Pitts took quite literally when exhibiting Home Is Not A Place, which opened in the Graves Gallery, Sheffield in August and is moving to Stills Gallery, Edinburgh in March 2023. Housed above Sheffield’s central library, Graves has been open since 1934 but Pitts never went as a child – he says he didn’t even know it existed. Determined to make his show more welcoming, he included sofas and a mock-up of his lounge in the 1990s, and while there are photographs on the wall he’s also included lo-fi family albums. Aware of the financial difficulties that working-class people are facing this winter, he’s happy for it to be a place people can get warm too, something akin to a community centre

Whether it’s building a cosy space in a gallery, finding a more inclusive Afropean experience, or centring an overlooked perspective on Britain, Pitts’ projects are all underpinned by a sense of community. He wants to highlight different narratives but he also looks for the links between them; it’s ‘a travesty when we forget the potential for solidarity’, he says. ‘Someone who’s Jamaican and someone who’s Irish, who lives on the outskirts of Manchester, maybe they have more in common than this hierarchical structure implies, this everyone jostling for position above everybody else.’

‘Thinking about culture, I’m looking for those similarities. This series is about Black Britain, but every time I’m writing or putting together something I’m trying to have it be about more than that. I’m trying to look at possibilities. I’m trying to think about different histories so we can think about different futures, because alternative pasts can suggest alternative futures.’