From issue: #23 Seen/Unseen

Recently awarded the inaugural Emerging Photography of the Year award by The Saltzman Family Foundation and the Center for Photography at Woodstock, Keisha Scarville also attracted acclaim for her first book, lick of a tongue, rub of finger, on soft wound, which was shortlisted for the 2023 Aperture/Paris Photo First PhotoBook Award. Her use of collage and her approach to the photobook knit together new narratives from existing stories, argues Pelumi Odubanjo, paying homage to under-acknowledged diasporic histories

What feelings of intimacy are truly specific to the photobook? Bound in a form often inseparable from ideas of sequentiality, decipherability, and narrative, the photobook can prompt questions around what it means to consider an image as a physical object, touched, held and manipulated at the holder’s will. In its page-by-page format, a photobook can permit an encounter with the image which may be slowed down, hurried, skipped, or paused. It is in these moments of encounter that one can contemplate what it means for certain photographs to be compiled between, within, and against one another.

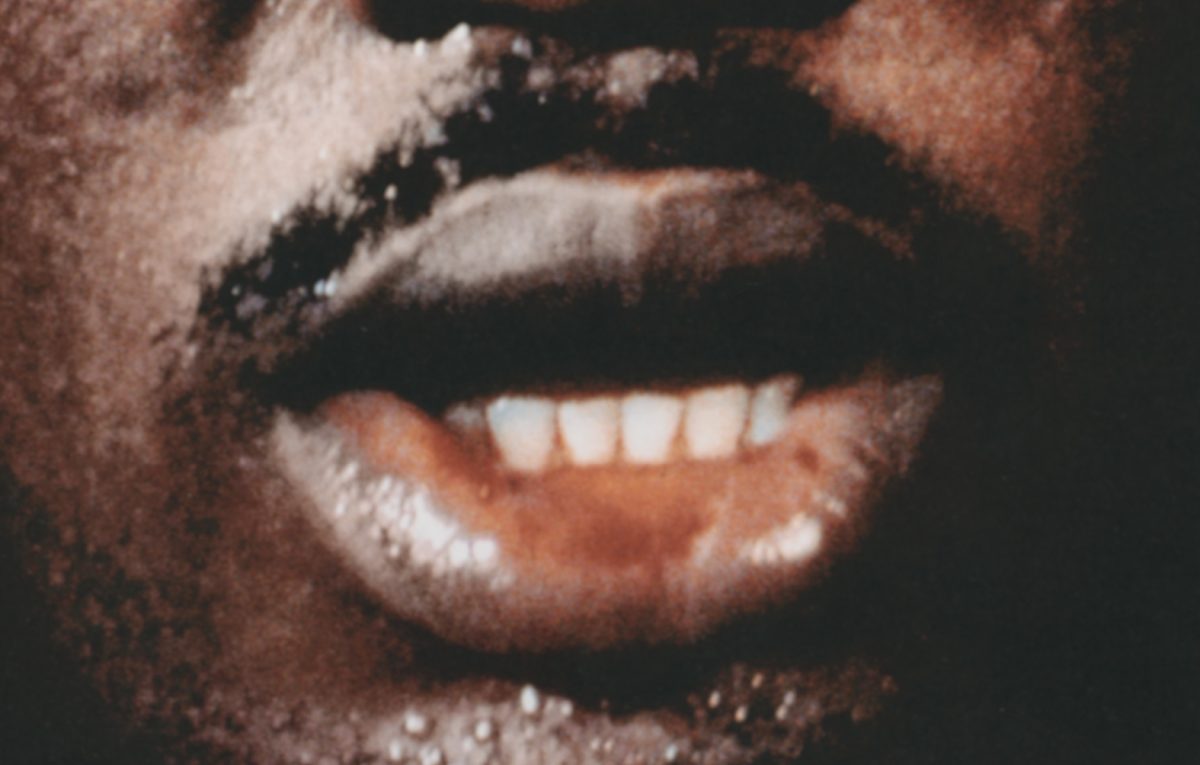

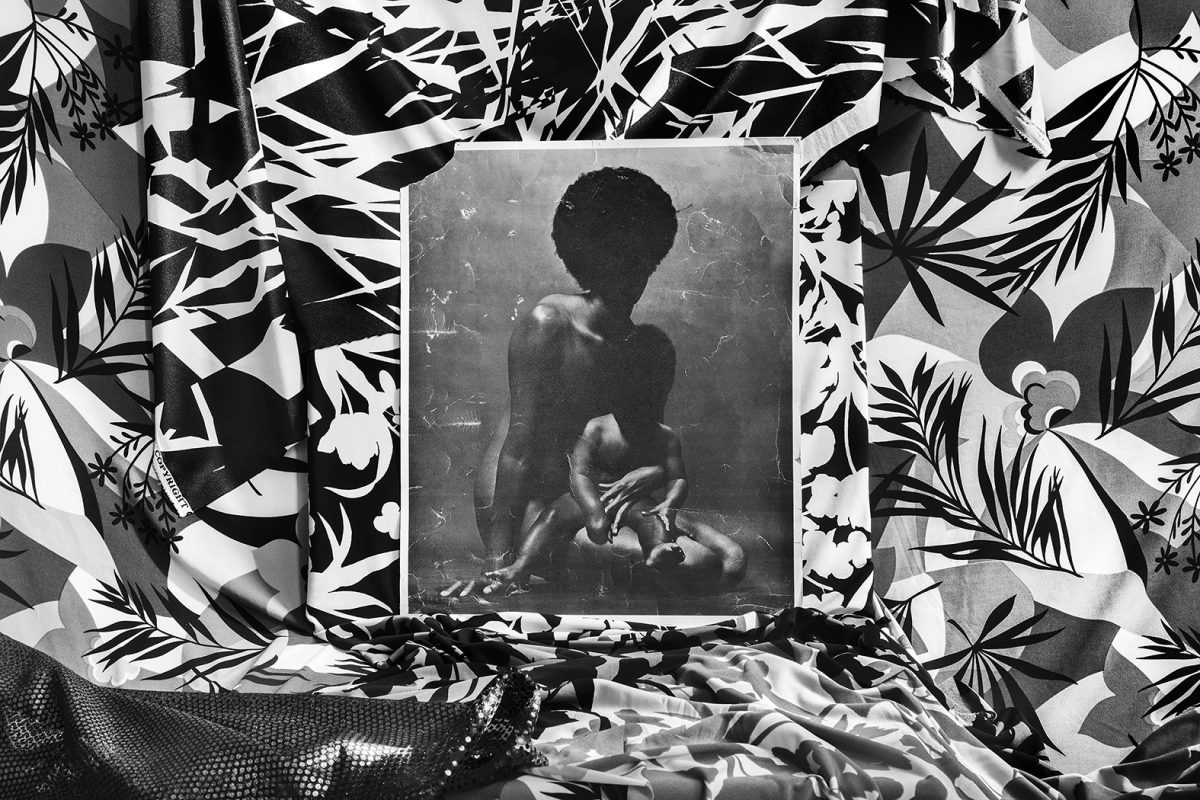

In her latest monograph, lick of a tongue, rub of finger, on soft wound, American artist and photographer Keisha Scarville playfully experiments with the potentials and possibilities of the photobook. Scarville creates moments of expressive enquiry into what it truly means to create an image, but also, more importantly, to restore it. Selecting archival, vernacular, and found images, alongside various examples of text and sketching, Scarville asks her readers to directly interact with fragments of her personal, collective and ancestral narratives, expanding these entities and allowing them to coalesce and intertwine like memories.

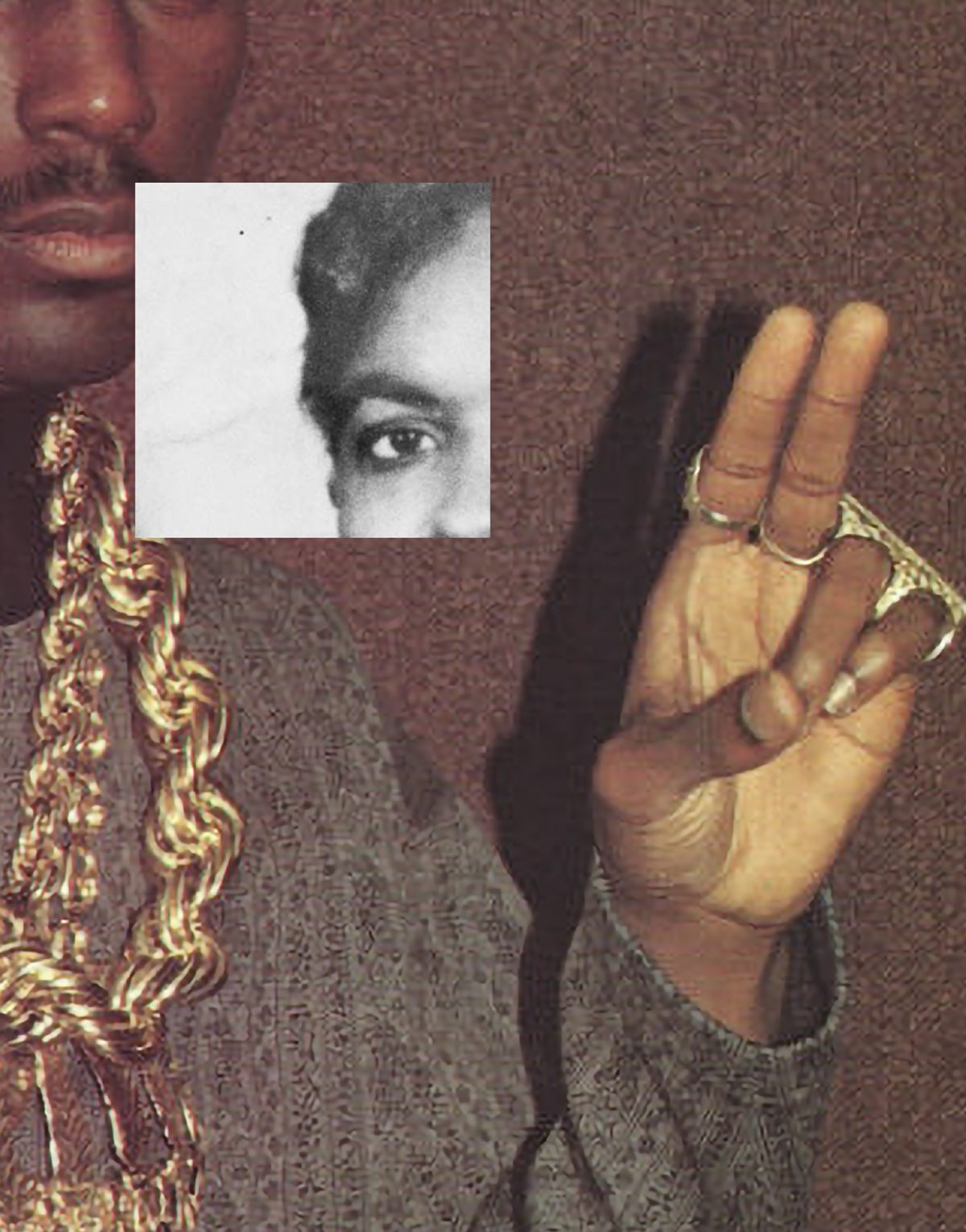

Oscillating between what is film or digital, what is grainy, obscured, or distinct, and central to Scarville’s probing of the limits and expansions of these visual forms, is a commitment to the language of collage. Ever-present throughout the book, collage becomes a technique which cultivates itself in different utterances, becoming a material and method which allows Scarville to disembody and reconsider ideas of time and space, in the context of photographic practice.

Intimate collages

Collage has long been regarded as an intimate method of art-making. From the early experiments of British Victorian women, and their compositions of photographs and watercolours, to methods of patchwork and quilting used by 1960s African-American women as a means to depict Black-American narratives, collage can become a conduit for fragmented narratives of personhood, environment and place. Moreover, collage can become a practice of ritual in which the material may be a portal to access memory, both personal and collective. In lick of a tongue, collage appears across the pages in disparate yet conjoining ways, used not simply to reassemble collated images but to restore them in the present time.

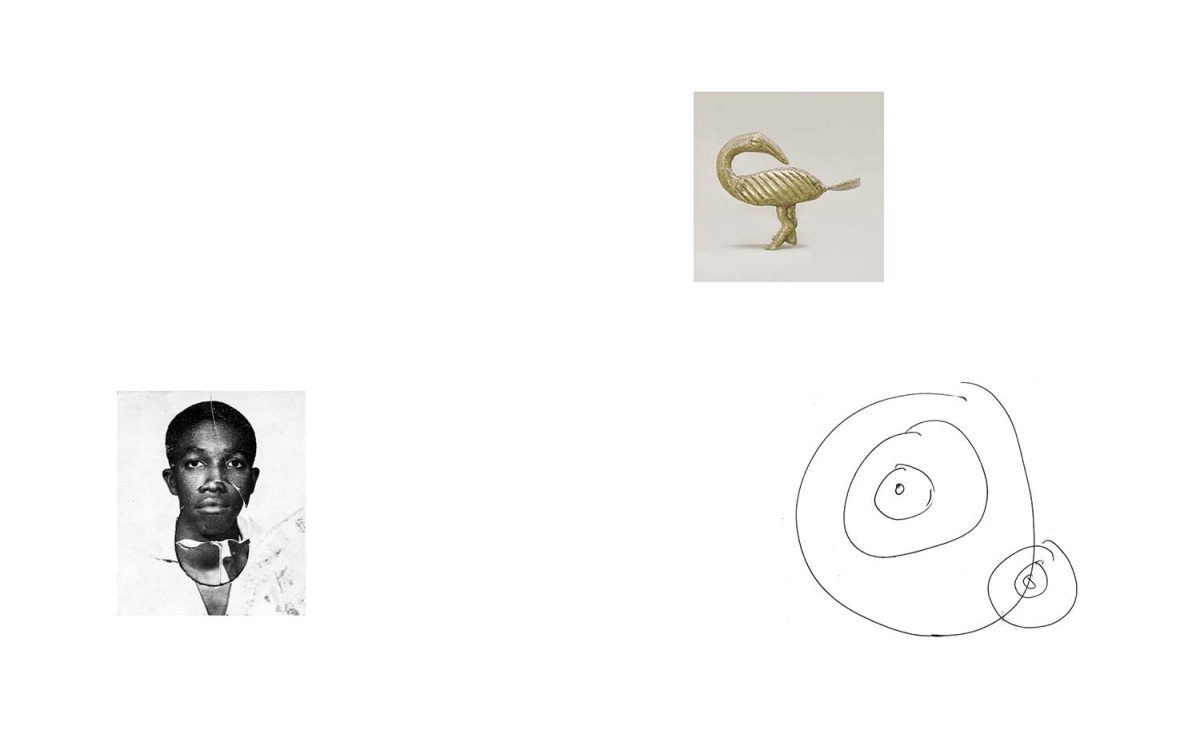

In one example, spread across a two-fold page, Scarville brings together three distinct image forms and visual languages – the archival, the hand-drawn, and the found image. In a format which reoccurs throughout the book, on the far-right side of the page, we see a small, square digital image of a golden object which embodies anthropomorphic qualities, existing as not quite still, and not wholly animated. The object stands with its weight on one leg, its delicate carvings made visible by the deeply shadowed yet still golden marks.

As we move anti-clockwise, we land on a photograph of a man who might be related to Scarville, the image bearing some of the hallmarks of a family archive print; it looks like an identification photograph, perhaps a passport photograph, though it’s shot in black-and-white. The man’s eyes stare directly into the lens but, leaning closer in, we can see a peculiar oval-shaped dent which contains another mouth, similar to that of the man photographed, but also an edge which dislocates itself from the wider image. It’s an intervention that contorts the photograph within the original.

The final visual component of the page takes on a different language as we see what appear to be hand-drawn circles, slightly imperfect and beginning to morph into spirals as they build and exist within one another. For me, these spirals become the meeting point of the two other images, a marker and direct extension of Scarville’s own hand.

In this personal mark-making, I feel an interrelation at play between body, time, performance, memory, and production, each making a statement towards a philosophical perception, intertwining and enacting an ecology of past and present, ancestry and death. They are concerns across Scarville’s practice but in this instance, her hand becomes a portal, a passage, and a way of movement into these images. In doing so, she creates an atlas of images devoid of linear chronology, and in perennial transformation. What does it mean for these images to be compiled in such a specific form?

In his 2021 essay Spectres and Textures: The B-side Wins Again, writer and photographer Johny Pitts asks what it might mean to read images in an “off-beat” approach within a context of (in)visibility, and how such an approach may be used to foreground those who inhabit the presumed margins. The B-side takes its name from records which, traditionally, have primary A sides and more secondary, less noted B sides. For Pitts, Black practitioners have often championed the latter, “because of their enforced proximity to it”. “Stories outside the stories, unofficial narratives…Hidden, spectral stories,” he continues and, for Pitts, these are the B-sides.

Hidden histories

In lick of a tongue, images are asked to exist at a rhythm and pace that attunes to Pitts’ idea. Once we, as viewers, allow ourselves to be consumed by the image in the raw, unfiltered form Scarville presents, we may begin to understand that, for her, the photobook does not simply exist as a didactic form, delivering information through a singular tone. If we were to think about lick on a tongue as an album, rather than a book, it might change our viewing experience.

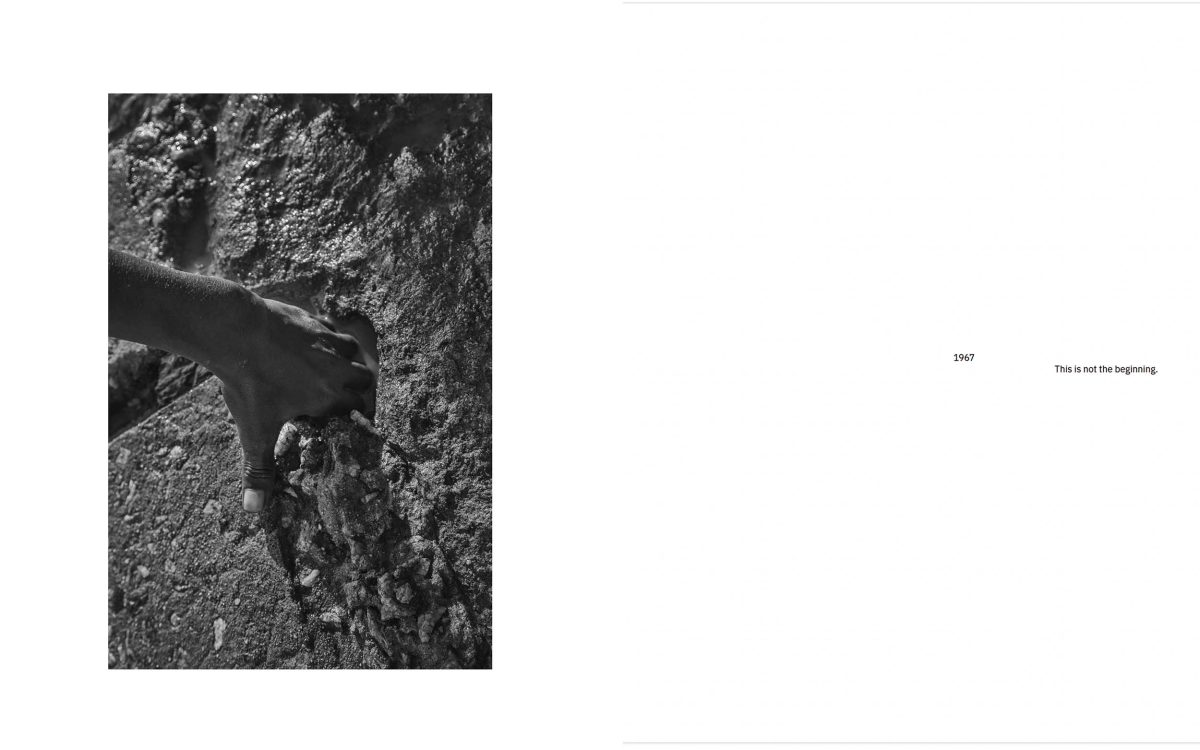

On another page, gently tucked behind a spread which reads “1967 This is not the beginning.”, Scarville invites us to enter the unbounded space of the night sky; positioned at the edge of the right page we find two presumably archive images. Actually, they are halves of a single image that has been divided and displaced, separating the touch of the two people who exist(ed) within it. These individuals appear to be a couple, their hands and arms comfortably wrapped around and within each other, even in this separation.

Photographed in a domestic space, the two figures reflect each other in their monochromatic outfits and in their positioning, appearing almost at equal height despite the fact that the man on the left is seated, slightly leaning on his stool. Through Scarville’s intervention, the fragmentation of this family photograph does not suggest division but instead a shared space, one of kinship, and of a familial tie that exists beyond physical proximity.

For me, pages and images such as these do not exist to be consumed in one single form. Thinking further into the expanded language of collage, this book and this record of images exists in the realms of montage, compilation, and remix. In this context, we can understand this collision of materials not solely as something to be blocked, obscured or laid upon, but instead as something which takes on many forms, including that which is heard, felt, and touched.

The album, whether the family photo album, musical compilation, or record of items, is a space which dissembles notions of how we must read or consume things, whether personal, documented, public or archival. This space of the album allows for a kinship of images, one in which Scarville, in her process, becomes the vessel of collage, compilation and montage, the conduit which holds these disparate pieces, languages and works together.

New cartography

As I sit holding Scarville’s book, I feel I am holding a photo album, an object familiar, intimate, and cherished. Scarville creates a visual cacophony of composition, light, shadow, bleed, and clarity, and a genealogy and lineage of people who may be family members, strangers, distant memories, or abstract creations. Scarville, who is of African and Caribbean descent and Guyanese ancestry, is no stranger to what it means to have a history and heritage abstracted. Her book’s form emulates that experience.

In this cartography of images, the book’s pages unravel within one another. From land to water, from skin to fabric, and from found to revived, lick of the tongue is a speculative endeavour, slipping between and beyond fixed ideas of how we, as viewers, should encounter and make legible certain images. As we journey through these various lands and textures, we are asked to replicate a journey of movement and re-emergence, Scarville echoing stories of migration and adaptation such as that of her parents, who left Guyana for the United States.

Scarville testifies to the ontological potentials of diasporic presences, making visible a collection of images that allow us to feel her emotion, her love, and her fascination, and her curiosity for the potential of the photograph.