From issue: #12 Time

Interviewed by Julia Bunnemann, Photoworks

Kíra Krász (born 1995) graduated from the University of Brighton with a degree in photography in 2019. She now lives and works in Hungary. Her work focuses on the interaction between images and their physical properties.

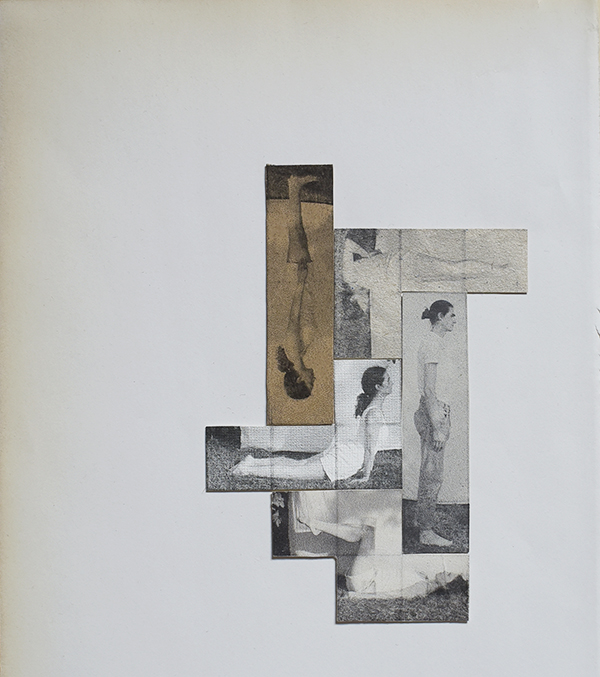

The series Squaring each other to fit as the space will be tiny, the days will be long started in 2020. Krász spent the first lockdown confined in a room in Hove (UK) with her partner George. The couple would transform the room according to their daily needs. Having been introduced to the videogame Tetris (designed by Alexey Pajitnov) at the start of this confinement, Krász soon connected the gameplay to how the couple ‘arranged’ themselves in the space. Squaring… encompasses timelessness by looking back at what we called the ‘new normal’ in 2020 through the lens of a 1980s video game classic and the Hungarian conceptual art movement.

Squaring each other to fit as the space will be tiny, the days will be long was realised during lockdown. Could you tell us how it developed?

George and I spend the confinement in one bedroom of a shared two-bed flat. For us, the space became a living room, dining room and bedroom, as well as a studio ‘equipped’ with low ceilings because of a mezzanine. Every day was a challenge to organise us and our objects. We had the most troubles with ourselves: there were just too many limbs for a tiny room.

Tetris has served as the basis for various scientific research project due to its tendency to thicken the cortex, improve brain efficiency, and develop problem-solving skills. We got used to playing it every day. It was a way to accept that we might not have any answers to COVID, but we can change the elements around us. We had to adapt, conform and contort to the limited capacity as each of us was making and claiming space. As we improved in our game, we harmonised our interactions and attitude to each other. With regular flashbacks of pieces falling into place, we built the virtual tower of building blocks for our relationship. Our focus on Tetris and its endless tasks seemed like a challenge to tackle, which was manageable with conscious control. It was our competition – an outside challenge – that the mind needs in a life that has temporarily been transformed to take place inside the game and our headspace.

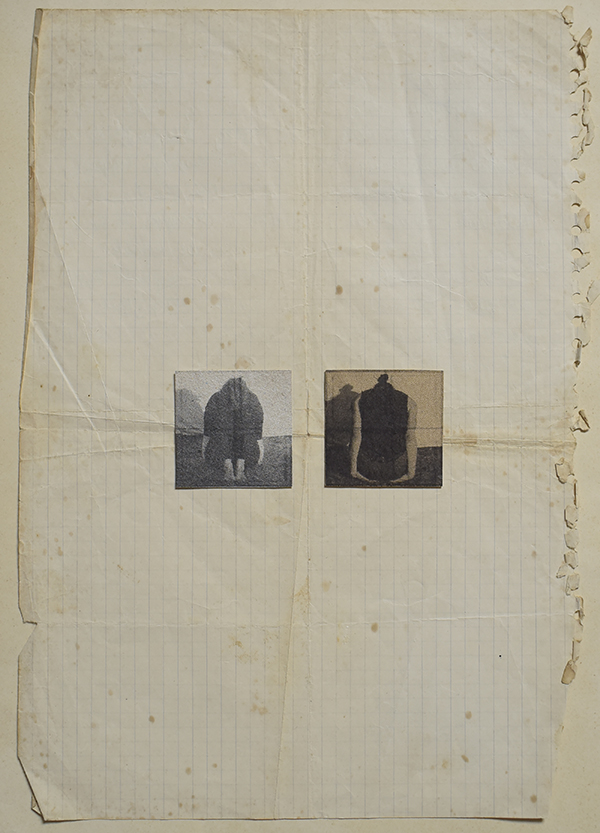

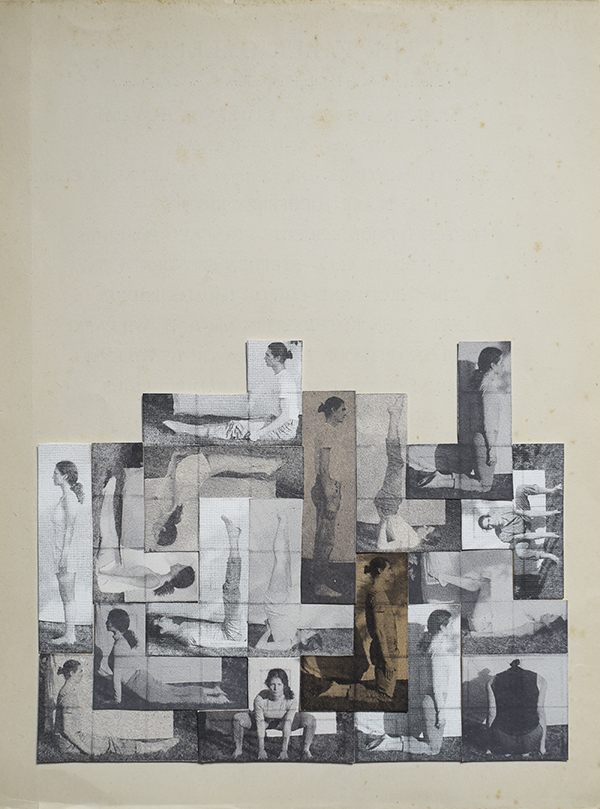

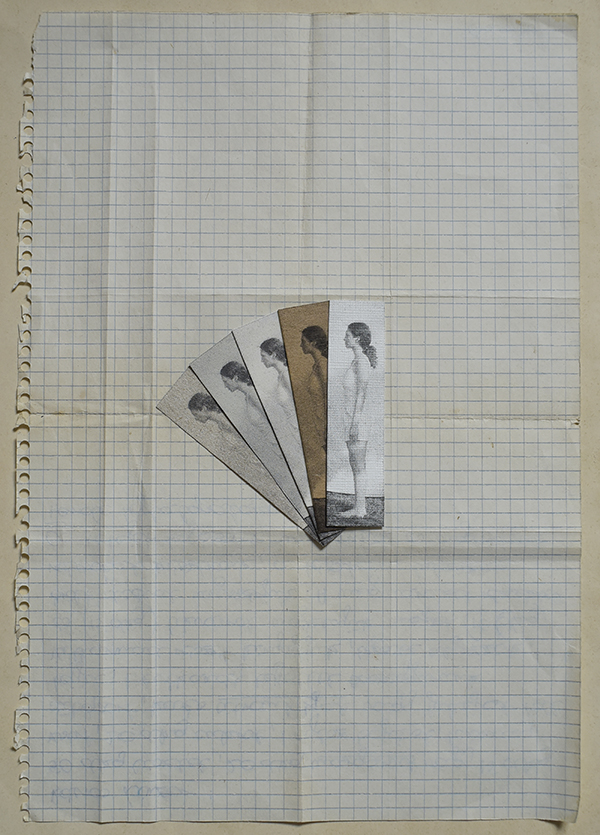

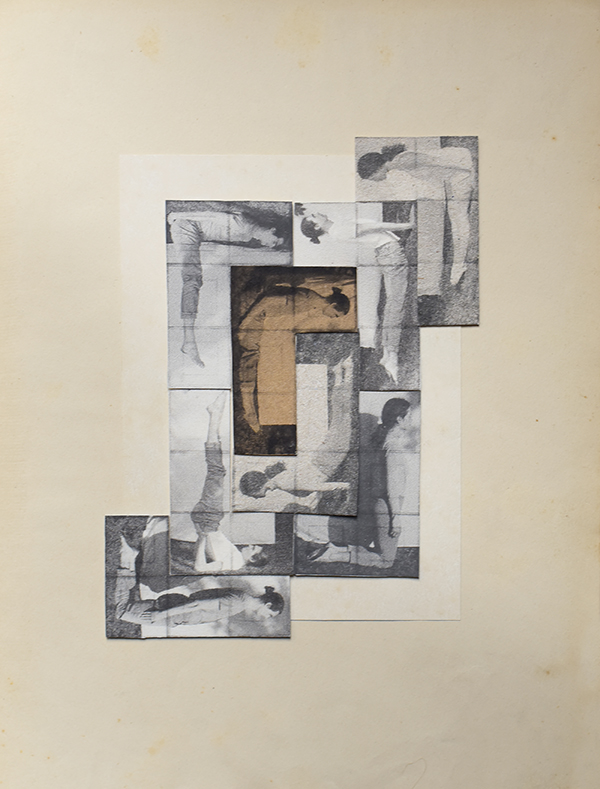

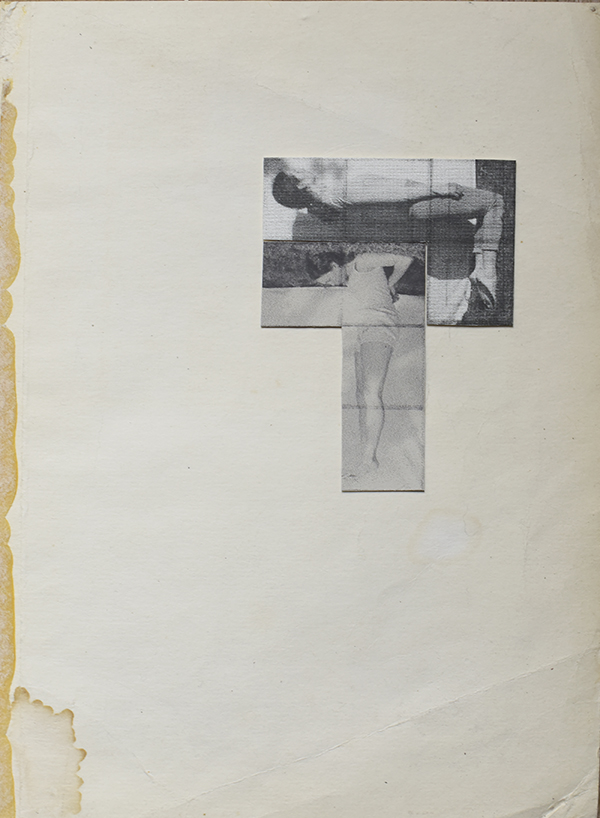

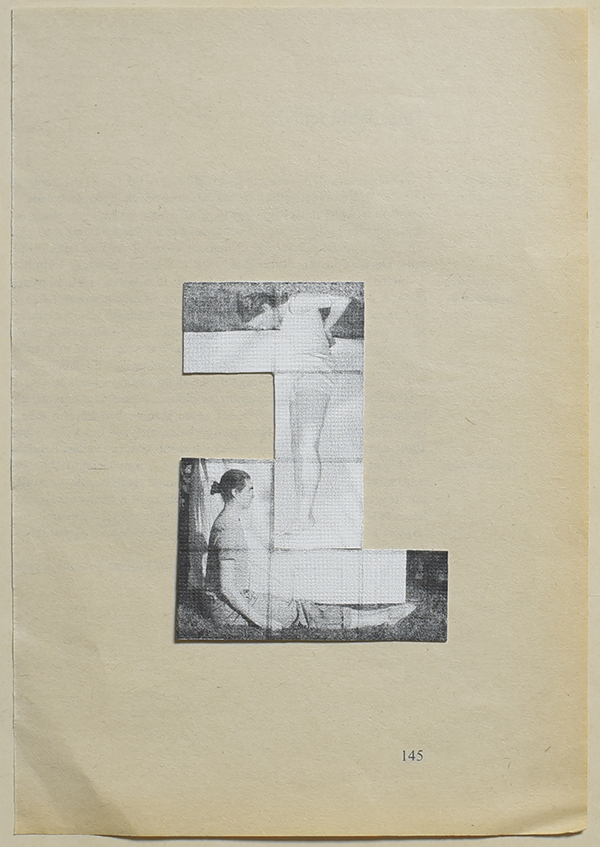

To convert this metaphor into a project, we matched Yoga postures to fit the Tetriminos (the four-square configurations of the game). Hand-drawn shapes were overlayed onto the images, printed, cut out and positioned upon papers from our recycling. The process was an opportunity to depict balance, completion, and harmony of action by adjusting shapes. Frequently we struggled for equilibrium: these compositions revealed the weight-relations when one of us was more affected, emotionally or mentally, in the situation.

How is this series embedded in your practice?

I am always curious about the possibilities that photography can provide: layering images, using various textures, montaging and experimenting with printing techniques. Collecting found material is also an integral part of my practice. When we entered the first lockdown, I was given an old printer, so I started printing on different materials I had saved up during the years and printing on the paper that we would put in our recycling.

I also like the ‘texture of age’, and I am intrigued to include old materials in my work. I don’t strive for my photographs to be neat, sterile or in any way perfect. I think some blemishes and some history will allow the prints to be more individual. I like little surprises while creating new work, so I test and alter each piece until I arrive at an outcome I am pleased with.

Despite the obvious relation to the game of Tetris, each of the unique pieces seems to be connected to the aesthetics of the modernist and the Hungarian conceptual art movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Can you tell us more about which work inspires you most?

Out of that era, I like the work of Géza Perneczky, Ferenc Ficzek, Dóra Maurer and lots of others, as I feel that there was so much room for the experiment – whether that be driven by light, by the self or by a process. Their photographs do not stop in time, they reveal variation and movement. Thoughts. Emotions. Everything. It is like reading a book, and it makes me want to try those methods, find those objects myself – it really triggers my mind.

My other side likes a more conventional style of photography, like Sally Mann’s, which is about aesthetic and the beauty of the everyday. I enjoy seeing people in slightly constructed photographs.

Photography is part of your practice. For the first time, you used moving image in your work. Would you still regard yourself as a photographer?

To include video was a process that came naturally and I only used photographs, so it was not too much of a jump. To reflect the daylight changing inside the room, I allowed the sun to cast shadows upon the photographs and the clouds to echo stop-motion. I was hoping to convey the feeling of sitting in the window, playing Tetris, looking out, watching the clouds go by, the time of day passing. The stop-motion also serves as a reminder for those who had played Tetris in their childhood or as a reference for those who have never played the game before.

Squaring… was realised during the first wave of the pandemic. Will you continue to work on the series?

I plan to make some more pieces, as many of my prints sold in Brussels as part of Hangar’s The World Within exhibition. I have ideas to explore further scenarios of our first (and then second) lockdown.

As I have now moved back to Hungary, I revisited a topic that has always been close to my heart. There is a sculpture park in close proximity at the foot of a stone quarry, with more than 100 contemporary and abstract pieces. The artists who created the works include the founders of the arts faculty of the university in my hometown, Pécs. The park has been a public and creative space since the 1970s. Despite being a tourist centre now – fenced off from nature – the sculptures are in need of attention as many of them are eroded or have weathered. I started to observe and capture these sculptures, their alterations and, using different paper techniques and layering, to unfold and unravel them in my own way.

Photography+ is supported by MPB.