From issue: #19 Image Flow

Born in 1988, Thai photographer Krerkburin Kerngburi grew up in the northern city of Chiang Mai. After graduating from the Rajamangala University of Technology Lanna in 2011 he started work as a freelance photographer, and from 2018-2020 he studied MA Photography at the University of the West of England, Bristol. Returning to Chiang Mai he experienced lockdown in Thailand, and began the series The Quarantine Report (2020-21) which he published with ARC PRESS in 2021. Focusing on free TV, this project considers how images are used in broadcasting in Thailand and beyond.

Photography+: How did you get into photography?

Krerkburin Kerngburi: When I was a child, I didn’t like to be photographed. But my mom liked to have family photos, so I started taking these photographs for her. I continued through university and started work as a freelance photographer, then in 2012 became fascinated with street photography. I shifted my focus in that direction, inspired by photographers such as Martin Parr, Martin Koller, and so on.

P+: Why did you choose to study photography in the UK?

KK: I didn’t choose it, the universe did. The UK was one of my dream countries to visit because it’s rich with art and culture, and home to artists I really like such as Martin Parr and Banksy. I wanted to learn something new abroad, improve my photography, follow my dream to meet Martin Parr, and watch football!

P: What was it like to go back to Thailand from the UK?

KK: Studying in the UK gave me new experiences and perspectives. For the first time I experienced freedom of thought and speech, and when I came back to Thailand, I got reverse culture shock as I saw things differently. I felt like things were slowly moving backwards in my home country. There could have been skyrocketing development, but change might have made those in power lose benefits. So things have been kept as they are, the same belief system, unfair capitalism, huge wealth gap, and junta regime.

In Thailand we can’t speak about everything in the public space, so I use photography to speak my mind and let people decode what I want to say. My work is satirical. I use humour because it is simple and straightforward, but at the same time it can subtly reveal meaningful undertones, encourage scepticism, and provoke new questions about the culture itself.

P+: What lockdowns were imposed in Thailand?

KK: In the first month [April 2020], the whole country was temporarily shut down. The government declared an emergency and introduced new measures and requirements including home quarantine. Most businesses had to pause operation and many people had to work from home. People’s movements were restricted by an emergency decree.

P+: Why did you start photographing the TV?

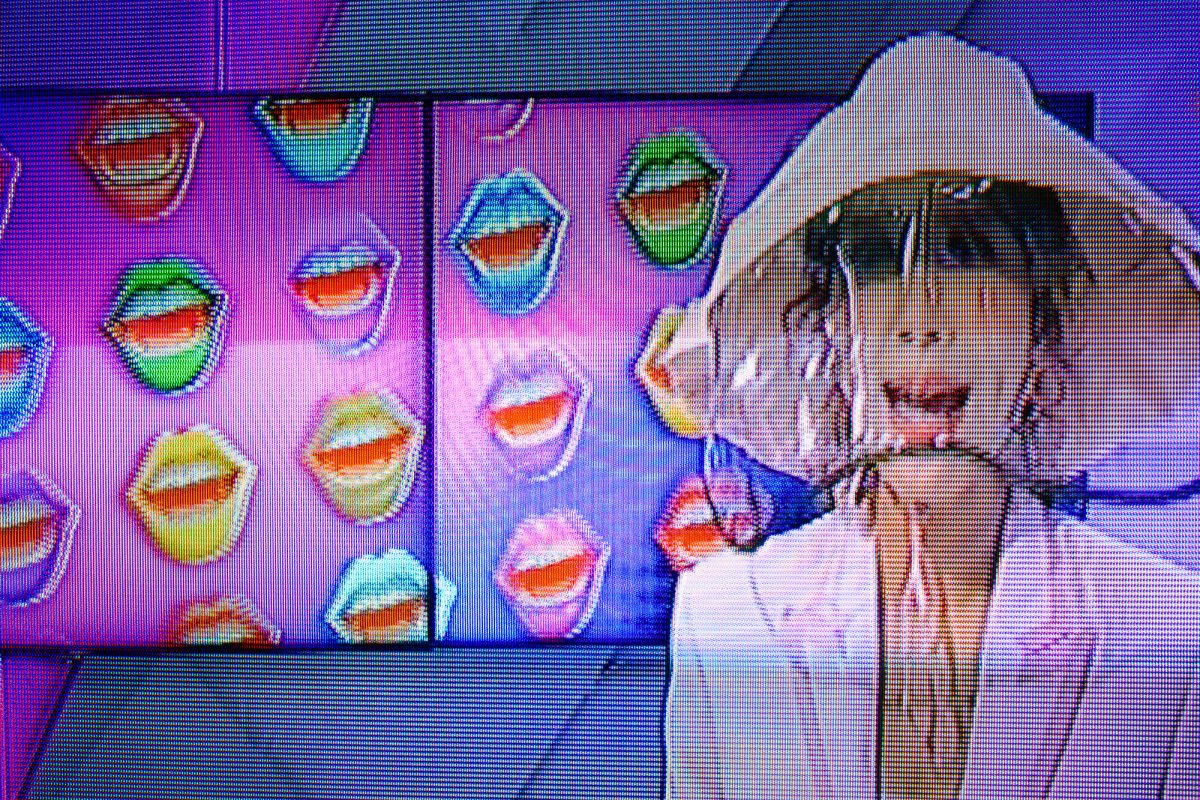

KK: I’m actually crazy about street photography, but the lockdown kept me away from the streets and led me to spending more time at home in front of the TV, watching the latest news reports on the Covid-19 pandemic along with other rambling free TV programs such as dramas, advertising and propaganda. I started photographing weird scenes on TV as an experiment, playing with distortion, glitches, and abstract colouring. It was just for fun at the beginning, using what I had available to keep myself busy creatively during the lockdown.

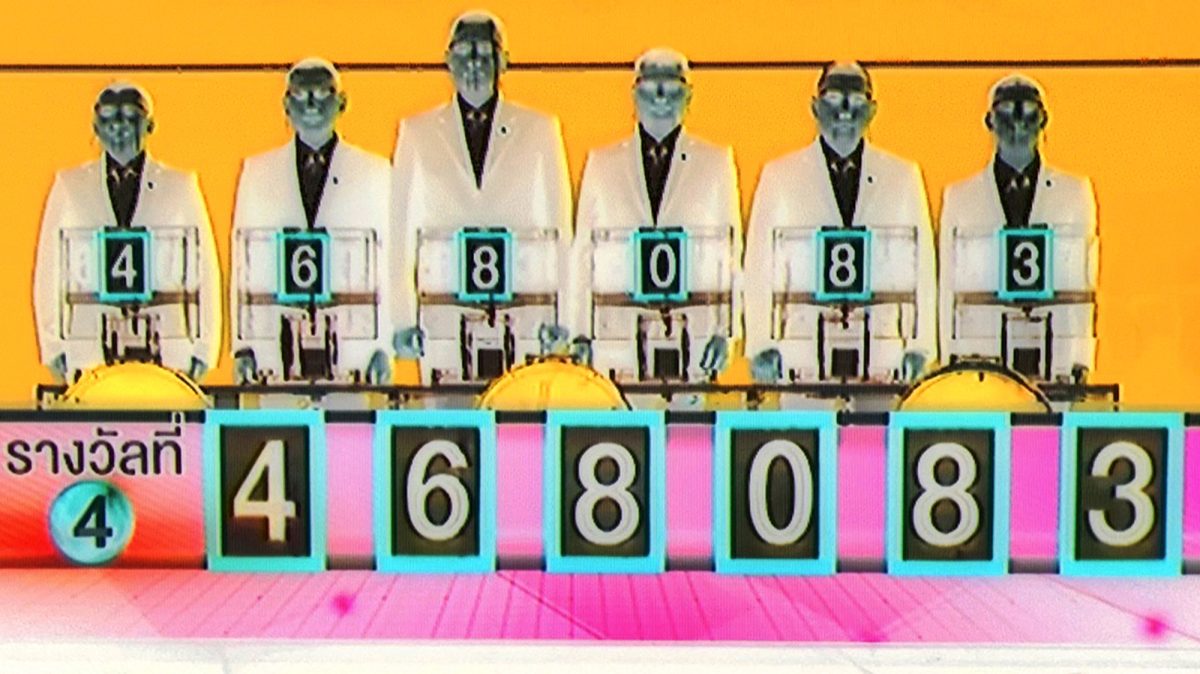

But this work reminded me of Harry Gruyaert’s cathodic screenshots [his series TV Shots, first exhibited in 1974], which captured era-defining world events and the banality of TV shows in the 1970s. The more I worked on the project, the more interesting and surprising it became. I grew suspicious about the influence of television in Thailand – TV was the primary source of information for most people during COVID-19, and it has played a dominant role in shaping social structure, trends, and culture, particularly in rural areas. Most Thai people are crazy about the lottery because they get a lot of info about it from the daily news report, for example, and the royal family has a news slot on free TV at about 8pm every day.

P+: How would you describe the flow of images in Thailand?

KK: There is a lot of photographic content including street photography, portraits, photojournalism, and commercials, all of which are mainstream. The media is quite free – most images are circulated freely, but some sensitive content can be restricted or censored, or might pose issues for the photographer, for example content about the King and the royal family, or the military government. A small group of people focuses on personal projects and tries to do something different by using photography for storytelling. Here there is everything – beauty, humour, weirdness, chaos, confusion, mess, which I find fun.

P+: You mentioned that you think images on TV help manipulate people. Do you think that particularly applies in Thailand, or is it the same everywhere?

KK: In my opinion it’s the same everywhere, but it’s quite obvious in Thailand.