From issue: #21 Thingification

Brought up in a working-class tenement block in Glasgow, Kirsty Mackay makes documentary projects highlighting the poverty in which some UK citizens are still forced to live, thinking through how to show and include those affected in her work. Her latest project, The Magic Money Tree, is an indictment of the cost of living crisis, in which she’s involving those she’s working with more than ever before

Kirsty Mackay was born Glasgow, Scotland, and grew up in the city in a working-class tenement block. Her area was mixed and next to a more prosperous district though, which meant Mackay could see social inequality from a young age. This experience underpins her approach to photography, both in terms of the topics she chooses and the way she approaches them. Shooting portraits and documentary images, Mackay tackles poverty without demonising or patronising the people who face it.

Her last book, The Fish That Never Swam (2021) was a deep dive into her hometown, which has the lowest male life expectancy in Western Europe. Mackay’s images show factors such as Glasgow’s controversial 1970s housing estates, which broke up working class neighbourhoods and rehoused families in isolated sites; Mackay’s portraits are sympathetic and often shot in her subjects’ homes. Mackay worked closely with these people, asking them to pose as they wanted and sharing her images before publishing. She also included interviews with many, keen to hold space in which they spoke for themselves.

Now Mackay has a new project, The Magic Money Tree, which follows people hit by the cost-of-living crisis in Bristol, South Shields, and Tipton. Mackay is working with three families, two youth clubs, some women she met through a foodbank, and a couple of others, and describes the project as collaborative, incorporating both her own photographs, drawings by some of those involved, and shots taken by the children on cameras she has handed out.

She started the project in early 2023 and, as we speak in September, has only just started to make and get back images and artwork. ‘It’s been a slow process of meeting and getting to know people,’ she says. ‘But it’s really taking off now.’

Mackay says the kids’ perspectives are key, particularly because some 4.2 million British children live in poverty; she adds that showing these youngsters helps diffuse arguments around the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor, because they so clearly don’t deserve what is happening. Children’s voices will be a big part of The Magic Money Tree when it’s eventually published, she says, maybe even a whole chapter, but she’s conscious that including youngsters also brings responsibilities.

‘What I really want to avoid is photographing a child in such a way that they can be identified afterwards,’ she says. ‘I don’t want to show them, and very specifically show that they’re growing up in poverty, and then in 15 years’ time they go for a job and someone searches and finds that online. I have to find a way that protects them. I already know that I’m not going to use people’s full names, and that this story is going to be told in such a way that it might not be obvious who’s in real hardship and who’s not.’

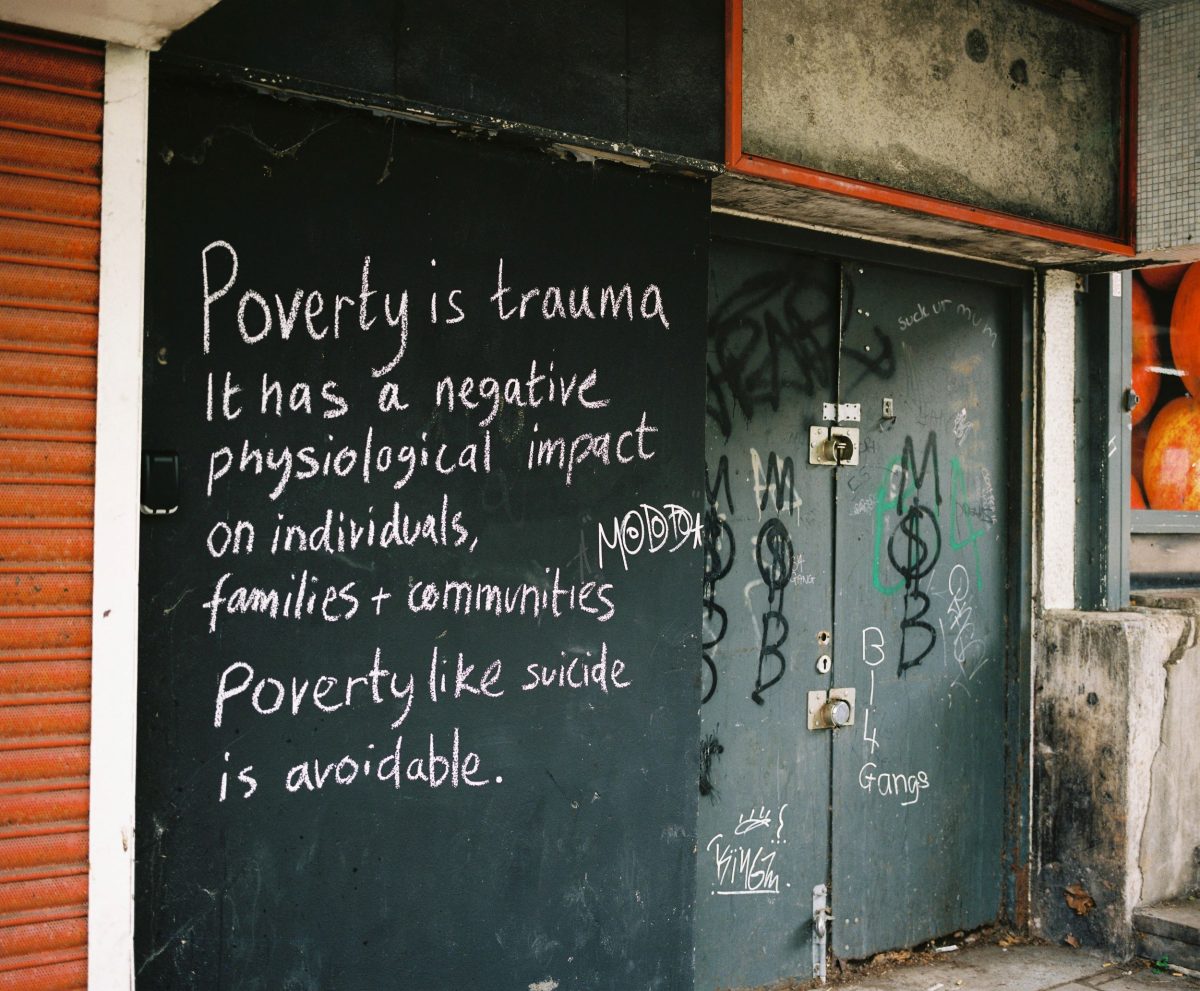

It’s an issue that other image-makers are thinking about, and Mackay says many UK charities are now unwilling to photography children in its wake. She’s sympathetic but believes it’s important to document, to show what is after all a reality for millions. And she adds that the families she’s working with are keen to speak up, to demand solutions for a crisis not of their making. ‘The actual story is that, especially coming after Austerity, this poverty is a political choice,’ she says.

Mackay met one of the families via a foodbank in Tyneside, where foodbank usage has gone up by a third in a year; she met the family in Bristol via her daughter’s school, after getting chatting with another kid’s mother. When I say it’s surprising, to chat with a mum about struggling, Mackay says it’s to do with her background, with growing up going without and therefore knowing the signs. In fact she says her background is a factor in making this work because other, better-off documentary photographers are somehow missing the issue.

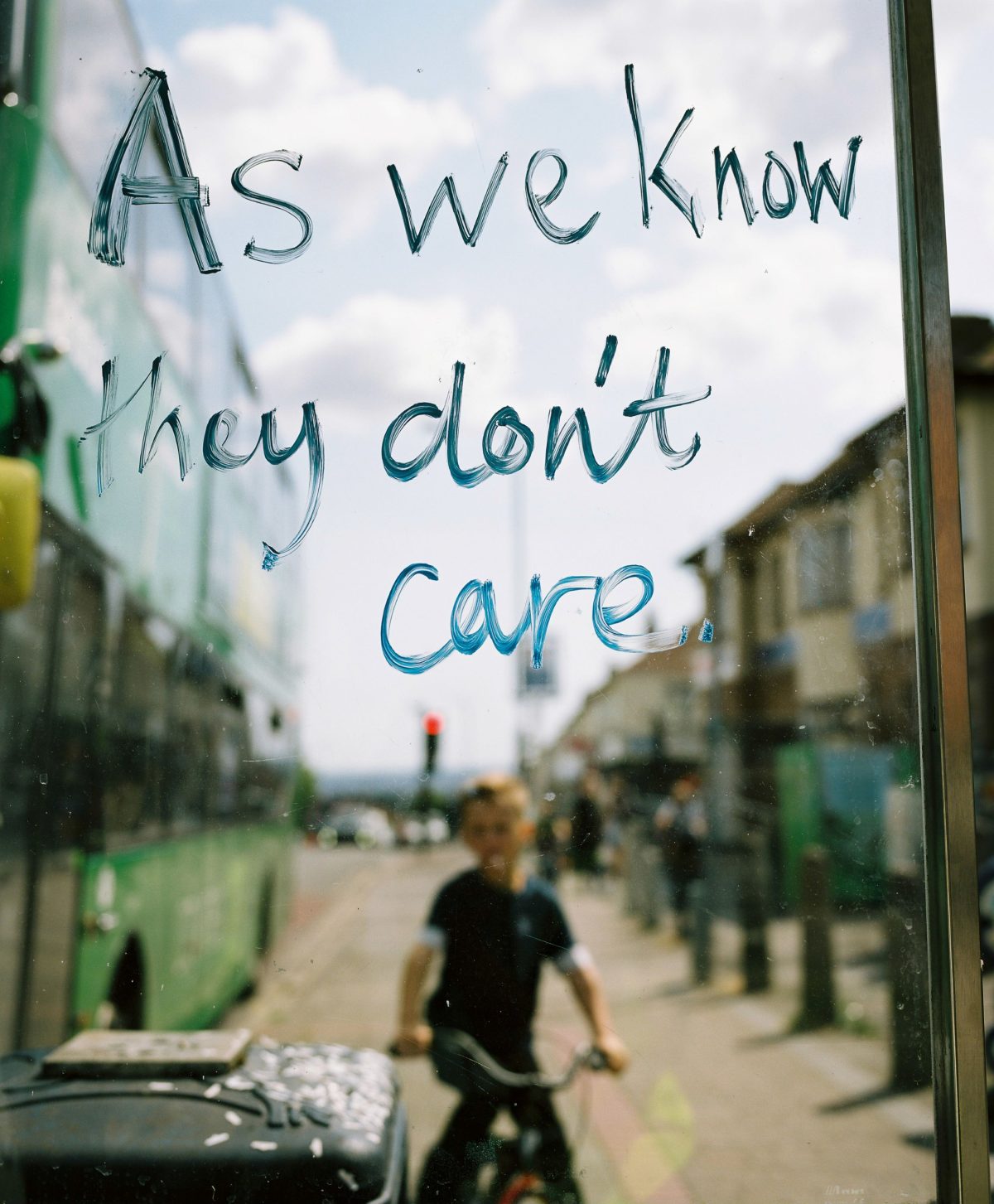

‘I think I see different sides, sides which I don’t see reflected that often in photography,’ she says. ‘I find it surprising there isn’t more work on this crisis, from 2008 onwards [the start of austerity] people’s lives have been impacted so much. I think maybe for some photographers, it just doesn’t touch them and it doesn’t touch the people around them. So then it’s just not a subject for them.’

Mackay believes class also feeds into concerns about showing poverty, with well-meaning image-makers trying to protect those affected, without actually asking them what they want to do. ‘Because I have working class roots, I just feel there’s another way,’ she says. ‘I know there are people who want to say something about what’s happening, and are happy to be pictured to do that.’

Mackay won a project grant from the Arts Council National Lottery to help make The Magic Money Tree, partly because she engages communities where it has low engagement; The Magic Money Tree will go on show at The New Art Gallery, Walsall early next year, then in Bristol and the north-east of England. Mackay points out she’s also an outsider in terms of this project though, photographing people’s lives but then combing the various strands to say something about the whole country. ‘In the end it’s about saying something collective,’ she notes.

She admits that it’s tricky, that she’s walking a tightrope between showing the difficulties without making anyone ‘a poster boy for poverty’, between showing people’s strength and the richness of their lives without making it look like everything’s rosy. Ultimately the key is listening, working long-term and just asking individuals what they think. And that’s also the case with the kids’ pictures, which Mackay says are a whole education in themselves.

‘I’ve found that, when they’re making photographs of another person, they’re not really framing that person in any way,’ she explains. ‘That’s really different to me. It’s liberating! I’m realising that what a photograph can be is much wider than this rigid way I’ve been locked into for so long. It’s loads of fun to see what the kids come back with, and widen my narrow view.’