'...the ground began to flatten out beneath us. It looked cut into brown squares, yellow squares, green squares, and big fat blotches of green where there was a forest. I began to understand cubist painting.’ Ernest Hemingway, on his first flight in a plane, from The Toronto Daily Star, 1921.

The sweet taste of landscape is just the sugar coating to a bitter history of disguise, occlusion and obliteration. Or at least that’s what we’ve been told over the last three or four decades as the genre that was once compared to money – ‘good for nothing in itself, but expressive of a potentially limitless reserve of value’ – has become a systematically devalued currency. But now things are happening, suddenly the landscape is alive again, as the contests and conceits excavated from its history of representation seem to be finding their way back, by some peculiar rebounding, into the physical and virtual worlds in which we now live and work.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

Recently, driving along the M5 towards Bristol, dreamily distracted by the picturesque scenery of farms and warehouses, my attention was suddenly taken by the extraordinary sight of a vast complex of high-tech buildings, low-lying like an airport terminal but extending for what seemed like miles over an area the size of a small town. Nothing surprising in this perhaps, except that the entire structure was painted in a giant irregular brickwork of different shades of green. The variously shaded rectangular panels of the buildings immediately suggested two things in strange harmony: firstly, the abstracted patchwork of an English landscape, and secondly a surreal monument to the history of camouflage.

And yet the full implications of this unlikely but fitting embrace only became clear on the return journey when I was able to see the complex from a distance, as a blur on the horizon. Then it seemed to hover, not as a building but as part of the landscape itself. It was there but not there, a perfect patchwork of green fields – now slightly fizzing in the fading light of the evening, – laid over an actual land of indeterminate scrub. The architects, we suppose, ironically sensitive to the structure’s impact, both on the rural scenery and local sensitivities, had disguised the building as an English landscape. For that visionary moment on the motorway, the full romance of the endeavour and its glorious effects now perfectly clear, the new Morrison’s supermarket distribution centre near Bridgewater became my favourite building in the world. According to a survey conducted by the Bridgewater Mercury, however, locals agreed that the building was ‘an eyesore.’

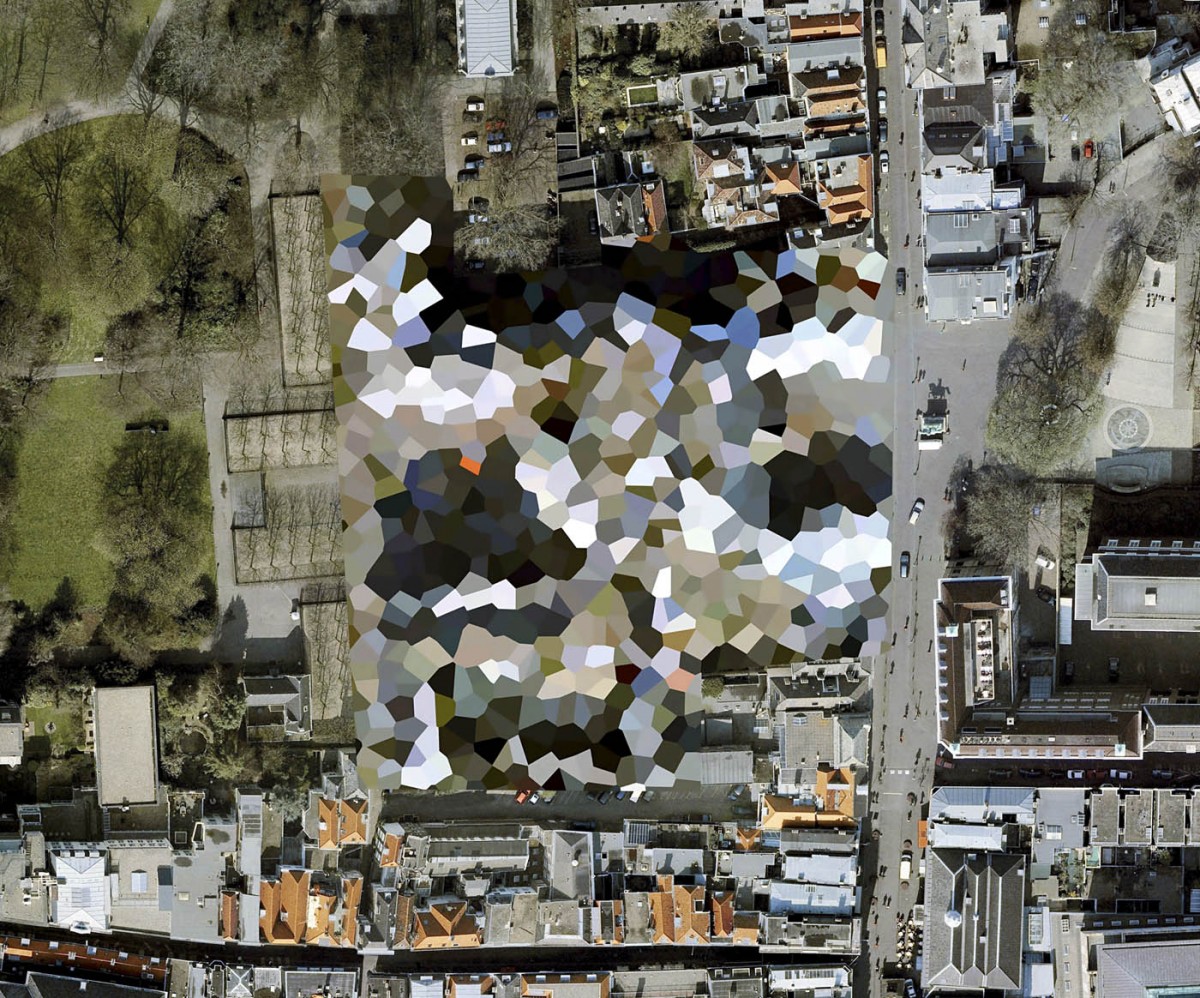

Mishka Henner seems to have made some similar discoveries while motoring on the information superhighway: odd, truly odd, incidents of digital camouflage applied to Google satellite imagery of sensitive sites, military and others, in his native Holland. His work comes with the beautiful, gift-wrapped irony, that Holland is one of the crucibles of the landscape form, one the genres preoccupied with depicting contemporary life that flowered in the seventeenth century. And so these strange digital emanations can be seen as part of a continuing tradition, one whose realisms were from the outset steeped in a language of metaphor and symbolism, of one thing hidden inside another. Also as this tradition has unfolded over centuries, the Dutch landscape itself has been reconstructed: land below sea level has been reclaimed then protected and cultivated by complex systems of dunes, dykes, pumps, and drainage networks. So the land, seen from above, is already one fractured and faceted by human intervention, a land becoming an abstraction of itself. In this context (as they are in Henner’s book Dutch Landscapes) the stylised polygons of this particular brand of digital camouflage appear as areas in which the landscape’s latent character has merely erupted into a new painterly intensity.

If aerial perspectives and abstraction go hand in hand – from the Futurist’s aeropittura to to Robert Petschow’s photographs for Eugen Diesel’s Das Lund der Deutschen (1931) or even Moholy Nagy’s high view from the Berlin Radio Tower (1928), for example – so camouflage, too, is embroiled in the story of art’s transformation in the early twentieth century. It is strange to think of cubism as a form of camouflage, but the links between the two were evident to Picasso and Braque, who liked to see First World War camouflage patterns as cubist derived. In fact their assumptions anticipated something more concrete, when artist André Mare, employed to develop designs for military camouflage from 1915, produced cubist inspired sketches as his working templates. Furthermore, from its origins in military balloon photography during the 1870s and 80s, aerial surveillance and camouflage have had a kind of competitive reciprocal relationship. In one particularly memorable instance during the Second World War, the Germans painted fake bomb craters onto the runways of their airfields to fool the allies into thinking that they were unserviceable. The craters were painted with great skill, including illusionistic shadows to suggest depth, but the allies’ reconnaissance images revealed that the shadows remained strangely fixed throughout the day while further stereoscopic analysis finally revealed ‘craters’ telltale flatness.

Traditions of landscape, obscuring as much as they reveal about lived experience and about social, political and military formations, loved by the privileged for the sense of order they bestow or equally by the dispossessed as melancholic visions of a lost proximity and attachment to the land before capitalism that never actually existed, have acquired a sense of theatricality. One thinks of John Berger’s remark in A Fortunate Man that ‘sometimes a landscape seems to be less a setting for the life of its inhabitants than a curtain behind which their struggles, achievements and accidents take place’, and then back to those awkward figures, ordinary men and women standing in front of painted backdrops in early photographic studios, suddenly brought forward, out of place. All these things, aerial photography, abstraction, cubism, camouflage, landscape, theatricality, seem to resonate in Mishka Henner’s mesmerising images. But overriding all this perhaps, and made more tangible by the artist’s astute selections, is the sense of a bizarre, unintended game being played out in which the strategies of surveillance developed by states and governments have come back to irritate and taunt them. Trust the Dutch to embrace the laborious process of digital disguise with due diligence and creative purpose: if it has to be done do it in style. In their hands, one can imagine the censorship drifting almost idly into the sheer pleasure of decoration, into the on-screen art of obscuring air bases or ammunition depots:…the Google operative takes another french-fry from the carton, turns away from his screen and swivels in his chair to shout across the office: ‘hey, anything else I can paint over, I’m beginning to enjoy this.’

Sources

This short essay has drawn on two vital sources of information. Firstly, the catalogue to the exhibition, The View From Above: 125 Years of Aerial Photography, curated by Rupert Martin and held at The Photographers’ Gallery, London between 9 December 1983 and 28 January 1984. And secondly, Peter Forbes’ excellent, Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage (Yale University Press, 2009). [/ms-protect-content]

Mishka Henner is an artist based in Manchester. He was included in the exhibition From Here On at Les Rencontres d’Arles 2011. His self-published book, Dutch Landscapes, is available at www.mishkahenner.com

–

Published in Photoworks, Issue 17, 2011

Commissioned by Photoworks.