From issue: #18 Science Fiction

The Photoworks Festival 2022 is inspired by a science-fiction author – as are a slew of other contemporary exhibitions, artworks, films, TV series, and musical outings. Why are science and speculative fiction so popular at the moment, and what does their current popularity tell us? Diane Smyth spoke with five curators to find out – Julia Bunneman and Raquel Villar-Pérez from Photoworks, Alexandra Muller from Le Centre Pompidou-Metz, Rebecca Edwards, from Arebyte Gallery, and independent curator Ekow Eshun

Photoworks Festival 2022 is inspired by Octavia Butler’s novel Parable of the Sower, which was published in 1993 but opens in 2024 in a United States of America falling into chaos due to climate change, wealth inequality, and corporate greed. The narrator, African American teen Lauren Oya Olamina, lives in a gated community that is eventually breached by desperate outsiders; she hits the road in search of a new home, gathering like-minded travellers on the way and developing a religion called Earthseed, based on the idea that ‘God is Change’.

Encompassing contemporary concerns over the environment, community, and wealth, Parable of the Sower now seems prescient, even visionary. It suggests that change is inevitable and that we might therefore build towards a better future; as a work of literature, it also suggests that writers and artists might help in the process. Taking their lead from this thought, the Photoworks curators worked with international partners Christine Eyeene in Cameroon and FotoGarten in Thailand to put together ten artists whose serves as a call to action, encouraging viewers to take responsibility for the world. As Olamina puts it in Parable of the Sower: ‘All that you touch you change. All that you change changes you.’

Parable of the Sower also provided a touchstone for another big exhibition in 2022, In the Black Fantastic at London’s Hayward Gallery. Including eleven artists working with various media, it considered how Black artists use speculative fiction to envisage new realities, in which people relate to each other and the environment more respectfully. One of the wall texts was taken from Butler’s novel, stating: ‘The Destiny of Earthseed/Is to take root among the stars./It is to live and to thrive on new earths./It is to become new beings/And to consider new questions.’

In August 2022, The Art Newspaper ran an article titled Who is Octavia Butler and why is the art world obsessed with her writing? while over in France, A Gateway to Possible Worlds. Art & Science Fiction has just opened at Le Centre Pompidou-Metz, including more than 200 artists and a whole section inspired by Parable of the Sower. Beyond Butler, science and speculative fiction are a running theme with, in London alone in 2022, exhibitions including Our Time on Earth at the Barbican, Alienarium 5 and Back to Earth at the Serpentine Galleries, Science Fiction: Voyage to the Edge of Imagination at the Science Museum, The New Worlds season at Somerset House Studios, and the Futures Past Sci-Fi season at Arebyte Gallery.

And science and speculative fiction are big in contemporary popular culture too, in the Black Panther movies, Atlanta TV show, and Beyoncé’s film Lemonade, to give just a few examples. But science and speculative fiction have been with us for a long time. Butler died in 2006, while Le Centre Pompidou-Metz’s show includes work dating back to the 1960s. Science Fiction: Voyage to the Edge of Imagination references Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, first published in 1818. So why the interest right now?

For Alexandra Muller, curator of the Pompidou-Metz show, it’s because our current way of life is clearly not sustainable. ‘We are living in a science-fiction era, a time in which our certainties are severely tested,’ she explains. ‘The idea for the exhibition was born in spring 2020 with the Covid crisis, at a moment that imposed the advent of a “liquid” form of the present, disintegrating our convictions and revealing an individual and social fatigue that seems to reverberate with the exhaustion of natural resources. When reality goes haywire, it is high time to look to science fiction, a genre for which questioning certainties and assumptions is a credo.’

‘There’s a certain interest now in the arts in showcasing a better future,’ agrees Photoworks curator Julia Bunnemann. ‘At the moment our reality is a bit grim and there are things that are daunting – things that even resemble Butler’s novel. During Covid we closed our borders, just as in Butler’s novels they close off their community. We didn’t share vaccines, we didn’t help each other. It’s a bit terrifying so you wonder, how do you react? And what can the arts bring?’

Ekow Eshun, curator of In the Black Fantastic, says something similar. For him, science or speculative fiction are ‘ways to consider other possibilities’ or ‘interrogate the strangeness of our children’s world’. As he points out, this sense of possibility might have been particularly pertinent to oppressed minorities over the years. ‘One of the conditions that Black people, people of colour have lived under historically, is the condition of being Othered,’ he notes. ‘Science fiction becomes a way to park current existence and tell other stories about who we are.’

Given this, it may seem curious that artists working with alternative worlds would choose photography as their medium. Often understood as a ‘window on the world’, it’s easy to think of photography as concerned with reality above all else. But many of the artists in these shows use photography. Johny Pitts’ Home Is Not A Place (2022) creates an alternative vision of the UK by showing the Black community too often left out of the stereotypes, for example, and his work is included in the Photoworks Festival. Felicity Hammond’s work Hidden Gems (2022), meanwhile, is a photographic collage combining everyday elements such as building sites and cleaning materials to form an otherworldly whole. Made for the Photoworks festival, it’s part of a longer project on mineral extraction that asks viewers to reconsider their relationship with consumer goods.

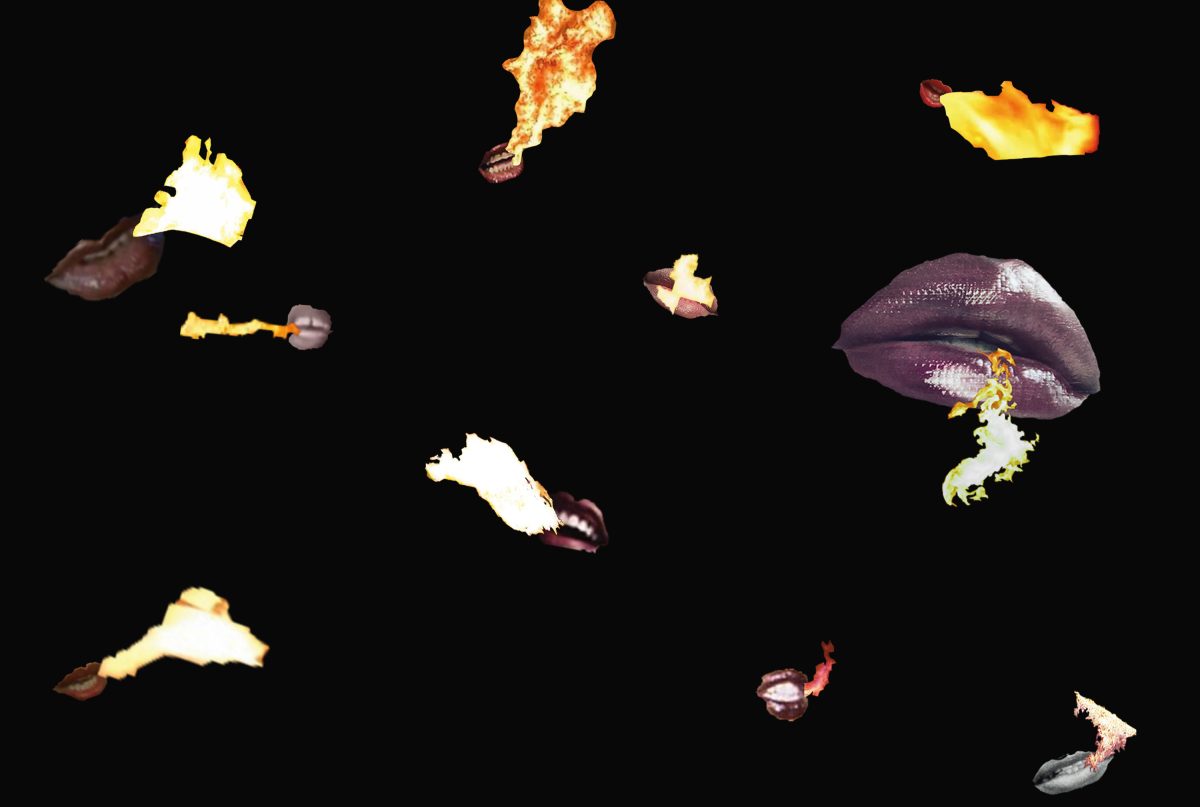

Over at In the Black Fantastic, Rashaad Newsome showcased funny, disturbing humanoid heads collaged from images of (for example) explosions, cupolas, and carved wood. Newsome also uses CGI elements, combining footage of glamorous trans dancers with a fictional but believable burning cityscape in the video Build or Destroy (2021). In the Pompidou-Metz show, meanwhile, Aida Muluneh’s 2018 image The Shackles of Limitations is a staged photograph.

In both cases, our tendency to read photographs as documents – irrespective of whether they are or not – becomes a useful tool to lending a convincing air to imagined fantasies. ‘One of the inherent operations of science fiction is that it likes to embody metaphor – an approach for which photographic collage or specially staged photographs are particularly suited,’ comments Muller. ‘Science fiction takes an idea, a concept, a symbol, and turns it into an artistic reality.’

In Arebyte Gallery’s science-fiction season Futures Past, meanwhile, artists are using photorealistic computer generated images [CGI] to similar ends. ‘When something is photo-real, I think there’s an immediate sense of understanding what that is,’ says curator Rebecca Edwards. ‘It gives you a pinpoint in your head of how to work something out. A lot of the artists [we’re featuring] use very photorealistic CGI. But it’s mixed with mysticism, eroticism, fetishism, architecture, so it’s photo-real but it’s not of this world.’

Edwards points to other techniques which, like photography, map or document reality in some sense. In these cases, however, the resulting images are so unfamiliar that they force the viewer to look again, to think more about their everyday assumptions. She points to Juan Covelli, who makes images using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) – machine learning networks that can make new data after being trained with existing data sets, for example generating new ‘photographs’. Covelli, who is Colombian, has used GAN to create images of archeological artefacts, found in his country but now held by Spain.

‘GAN works move in a very fluid, very unfamiliar way that we’re not used to seeing,’ says Edwards. ‘They give us this very amorphous image that’s neither one thing nor the other, [neither] digital nor photography. They mix the familiar with the unfamiliar and that creates a space for recontextualising and reimagining. They create space for being more present in the moment.’

And that’s a key point, because although science fiction and speculative fiction can be ways to think of the future, they can also help viewers rethink the present. Covelli’s work comments on the fact that Colombian artefacts are still being held by its former coloniser, for example, while Muluneh’s The Shackles of Limitations was commissioned by WaterAid to draw attention to the effects of global warming in Africa. Eshun links science fiction to the French Situationists’ post-war re-examination of the everyday, and with a wider project of decolonisation concerned with unpicking Western, Capitalist ways of seeing.

‘In the Western world we are all being collectively forced to confront a whole range of existential crises,’ he notes. ‘Climate change is the most acknowledged but also cases like George Floyd, which showed that racial inequality is real, rather than something that exists purely in the heads of people of colour.’

And that’s the perspective that drew Photoworks curator Raquel Villar-Pérez to Butler’s novel in the first place, and inspired her to draw out its themes for the festival. ‘Politics and economics have brought us here, to the current state of the world, and I doubt they can help sort out the mess,’ she says. ‘I think the work of artists gives us probably more hope.’