From issue: #20 The Graduate Issue 2023

Trigger warning – this article contains references to rape and sexual assault

P+ writer in residence Tanlume Enyatseng responds to the graduates picked out this year with a deep dive into the work of Bangladeshi image-maker Sumi Anjuman

In his 1962 essay The Creative Process, author and poet James Baldwin muses that the role of the artist in society is to “illuminate that darkness, blaze roads through that vast forest, so that we will not, in all our doing, lose sight of its purpose, which is – after all – to make the world a more human dwelling place”. Many artists attempt to spark change, foster empathy, and promote a more inclusive world through their practice, including Sumi Anjuman.

A pioneering visual artist from Bangladesh, she uses her work to question social norms, challenge traditional gender roles, and expose the manifold injustices faced by women and the marginalised in her country. Through powerful visual imagery, Anjuman sheds light on the struggles and resilience of the oppressed, amplifying their voices, and advocating for change. Her mixed-media project River Runs Violet is a moving protest against rape culture, for example, made in collaboration with a young assault survivor called Zana [the name is a pseudonym].

According to Anjuman, on average nearly four women, girls, and children are subjected to physical and/or sexual violence every day in Bangladesh, and rape incidents are on the rise. These statistics are terrifying, but Anjuman was moved to make River Runs Violet by both these facts and the representation of such violence in the Bangladeshi press. Stuck at home during Covid-19 she started to read about such cases, she says, and was disturbed “by not only the number of incidents but how the media portrayed rape sufferers”.

Working with Zana, her series relates her collaborator’s harrowing experience but also crafts narratives and visual representations that focus on patriarchal oppression, hoping to ignite a dialogue that demands change. “By integrating a diverse photographic manner, the aesthetic of my practice evolves into a poetic yet magic realism fabric to perform a non-violent dialogue within contemporary society,” Anjuman explains. “In parallel, my multivocal methodology echoes the notions of inclusivity, while the context of my artistic endeavour often attempts to make a strong cerebral as well as emotive impact on the onlooker.”

Anjuman’s own experiences also inform the work. Growing up as a woman in Bangladesh, she was often advised by family and wider society on how to avoid rape and assault. Rules and regulations around avoiding certain men, times of day, and locations implied she could create a safe space for herself, she says, a fantasy that women all over the world are told. “The truth is many women across the world live in cities of fear, cities they grew up in that they do not feel safe walking down the street in,” she says. “The idea of being alone in the street and two or three men walk past you, makes you afraid.”

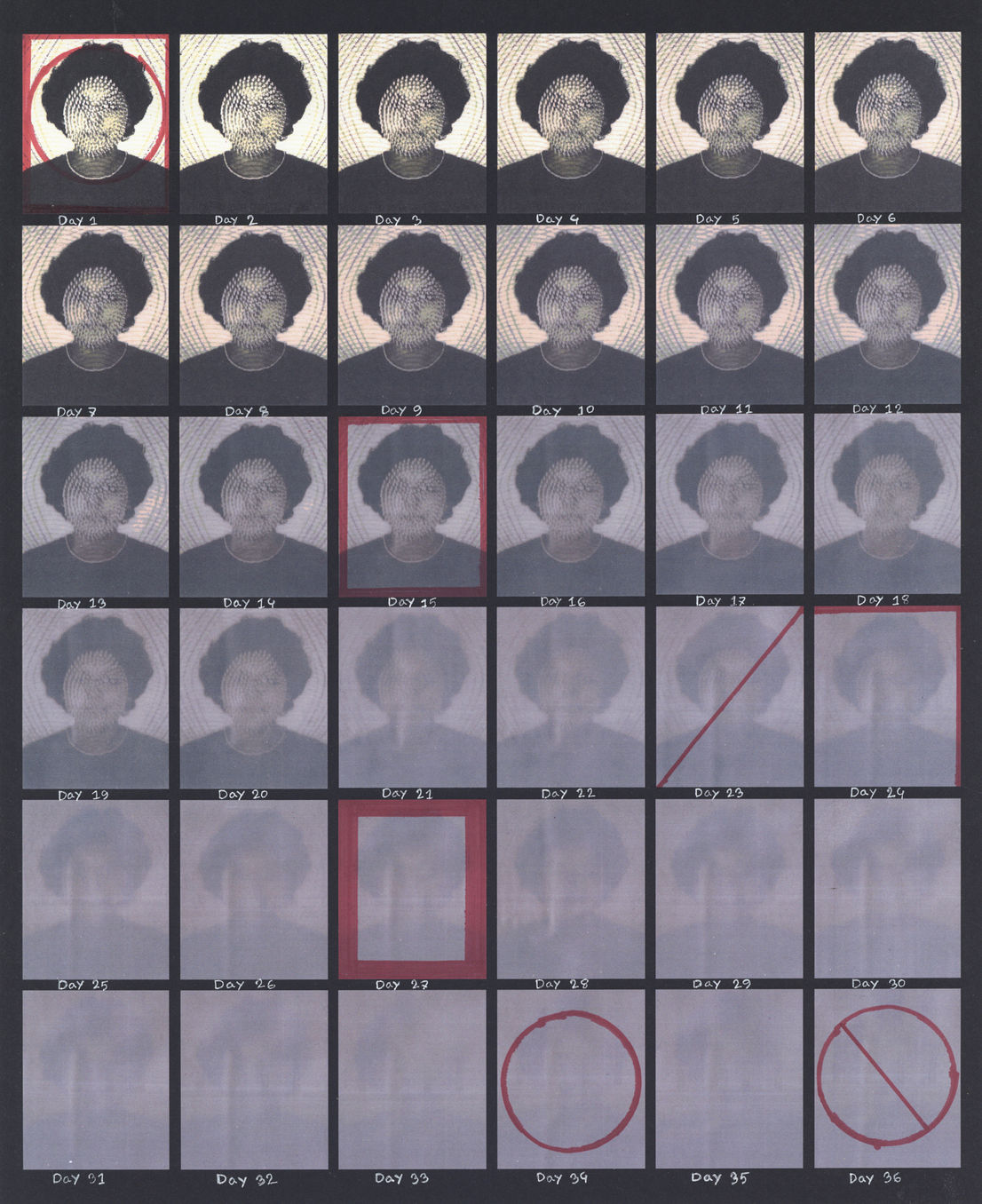

Zana was viciously assaulted for 36 days by her schoolteacher in 2011, at a prestigious institution perceived as safe. Dismantling all the rules and obligations set by society, her case demonstrated patriarchal dominance and her perpetrator’s sense of superiority. Anjuman had previously engaged with Zana as part of a LGBTQIA+ project in Bangladesh, and felt she needed to collaborate with her in sharing her ordeal. “I don’t want to hold all the power as the artist,” Anjuman says. “I wanted our voices to be heard equally.”

Zana’s experiences, as well as the artist’s own lessons from growing up, combine to create a multivocal visual correspondence. Their responses differ but work together, visually interrogating the specific context in which they live. This style and process came about organically over time, as the two collaborators exchanged experiences and visuals. Zana’s abuser was eventually sentenced to 13 years in prison in 2015, yet he was observed laughing following the verdict. In one of the images in River Runs Violet, a collage work features a screengrab from a news story around that unfeeling gesture.

“I constructed this spinal column-shaped collage of laughter,” says Anjuman. “This laughter mirrors the power bestowed on men by patriarchy, as a result of women’s disempowerment. In parallel, it uncovers the entire society’s state of patriarchal supremacy.”

Growing up a woman in a strictly conservative society, Anjuman says she has always lived in conflict with her community’s proscribed gender roles, roles which seem to control the actions of women and girls. But her interest in imagery was born in 2013, after the devastating collapse of a garment factory on the outskirts of Dhaka. Bangladeshi activist and photographer Taslima Akhter took a heart-wrenching image of the aftermath, and seeing it made Anjuman truly aware of the power of photography.

“When I looked at it, I felt that this was not an ordinary image,” she explains. “It had a lot more to say about the incident. It spoke to how lawlessness looks. It spoke to the failure of the state, and even the vulnerability of those workers who lost their lives.”

That sense of urgency inspired her to pursue a three-year diploma in Photography from Pathshala South Asian Media Institute in Dhaka, and she recently graduated from an MA in Photography & Society at Royal Academy of Art, The Hague. Her previous work includes Somewhere Else Than Here, a project documenting the lives of Bangladesh’s LGBTQIA+ community, which she started after two queer activists were murdered in 2016. Homosexuality is illegal under Bangladeshi law, which is inherited from the colonial British Indian judicial framework; the legal punishment for engaging in same-sex sexual activities is imprisonment, and wider society also refuses to accept LGBTQIA+ persons.

Stereotypes and misconceptions abound and, noticing how many of her close friends struggled to live openly out of fear for their lives, Anjuman worked with them to depict a parallel world in which members of Bangladesh’s LGBTQIA+ community could be themselves. Showcasing diversity and complexity, in the hope of presenting a more accurate representation of the community, this project aimed to both raise awareness of and humanise a marginalised minority.

Even so, Anjuman says she doesn’t see herself as either an artist or activist. Instead, she creates from a sense of responsibility, as a woman and a citizen of her country. “I see my practice having no neutral position,” she comments. “It is either I side with the position of the oppressed or the oppressor – and I would much rather find myself on the side of the oppressed.”