#26 Photography and Power

Who holds the camera? Who is being watched? Who gets to be visible, and who remains in the margins? We are not asking whether photography is political. That much is already evident. The question is: whose power does it serve now? And how can it be reclaimed?

In this issue, we explore how to reconsider photography not as an image-making practice but as a participatory dialogue that consistently interrogates, negotiates, and redefines power relationships.

This edition of Photography+ is edited by Amin Yousefi.

Featuring Danit Ariel, Jacob Lazarus, Thero Makepe, Fred Ritchin, Amah-Rose and the Werker Collective.

Read editor's note

In Orientalism, Edward Said showed how representation is not about truth but about power–how knowledge of the “other”, visual or textual, operates as a prelude to domination. The colonial photograph was not just an image but a tool of governance, of mapping unfamiliar bodies onto familiar hierarchies. In this light, photography emerges as a technical medium and an epistemological violence.

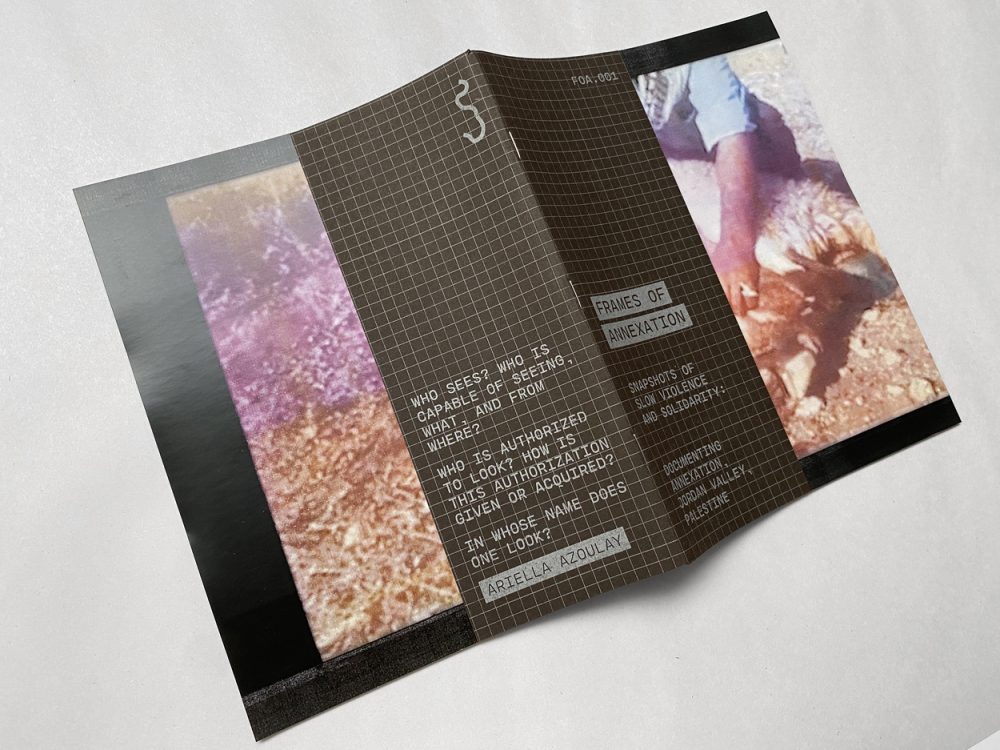

Even outside explicit colonial contexts, the camera often extends the logic of annexation. Its frame flattens difference, naturalises authority, and stabilises narratives that benefit dominant perspectives. Ariella Azoulay calls regimes of visuality not just aesthetic formations but political contracts–agreements, often unspoken, about who gets to appear, how, and under what terms. She argues that looking at a photograph is participating in a civic encounter: an ethical responsibility to those depicted and those excluded. Yet photography’s complicity is not the end of the story. Precisely because it is a site of power, it is also a site of rupture. The photograph holds within it the potential for counter-narrative, for re-framing, for resistance. It is a battleground between spectacle and testimony, between erasure and memory.

But this power is not always overt. As Vilém Flusser suggests, “There is a voodoo in every image.” Just as voodoo enchants or controls through unseen forces, images cast spells–not only reflecting the world but seducing us into seeing it in specific, often pre-scripted ways. Flusser argues that images bypass rational thought, intriguing the viewer with a seemingly transparent surface that conceals the ideologies within. They do not merely show–they enchant, and in doing so, they shape what can be known or even imagined.

In the context of our current image-saturated world, where algorithms dictate what is visible, where archives are weaponised or erased, this tension is more urgent than ever. The challenge is not only to critique photography’s historical uses of power but to imagine new uses: modes of image-making that do not extract but return, that do not classify but connect. To photograph otherwise is to disrupt the expected grammar of the image. It is to refuse the transparency of the frame and instead foreground its construction. It is to challenge the viewer not just to see but to question the very terms under which seeing becomes possible.

In this issue, we explore how to reconsider photography not as an image-making practice but as a participatory dialogue that consistently interrogates, negotiates, and redefines power relationships.

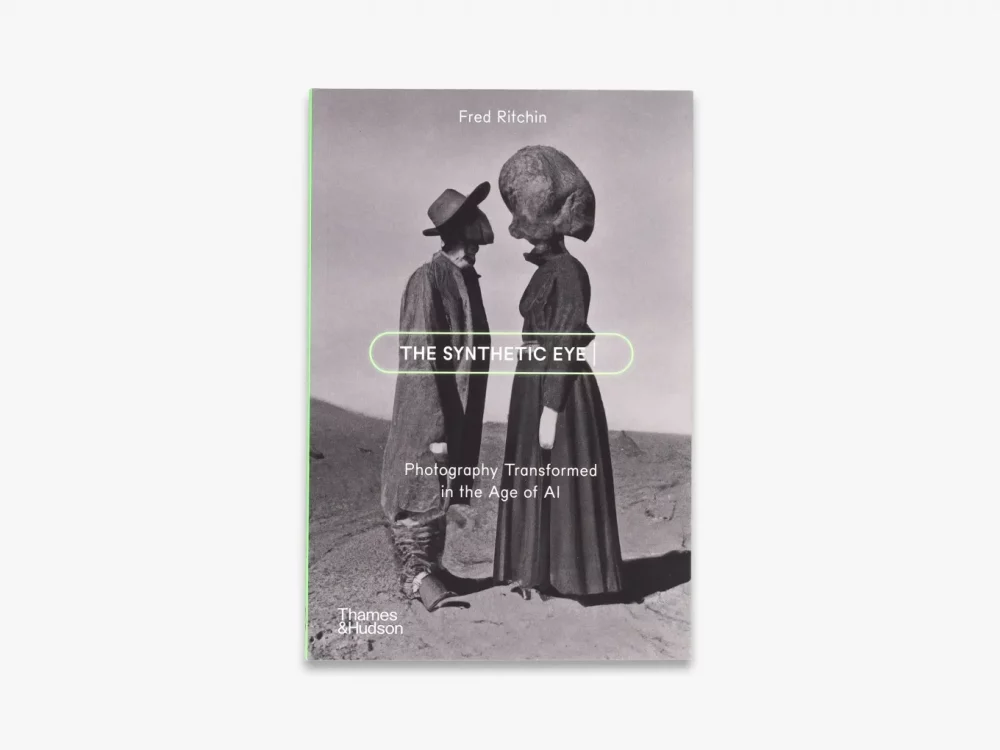

Fred Ritchin, in his article related to his forthcoming book The Synthetic Eye: Photography Transformed in the Age of AI, critiques how AI-generated images distort history and contemporary events. He discusses how these images can mislead viewers and manipulate collective memory, making it increasingly difficult to distinguish truth from fabrication. Amah-Rose Abrams writes about Resistance, a photography exhibition at Turner Contemporary, in which she explores how protest has shaped Britain’s sociopolitical landscape and how photography, in turn, has shaped the visual and cultural language of protest. Lillian Wilkie writes about the Werker Collective’s use of photography to challenge traditional representations of the labouring body, emphasising A Gestural History of the Young Worker, a photo-text installation that intertwines labour activism with LGBTQ+ issues. Angelina Ruiz, Photoworks’ Writer in Residence, in their final piece for the residency, explores Jacob Lazarus’s Frames of Annexation–a collaborative archive of occupation and resistance in the West Bank, assembled from body-cams, phones, and CCTV footage. Danit Ariel, Photoworks’ Curator, discusses why the power lies not only in the image itself but also in the relationship between the viewer and the photograph, and how personal connections and perceptions influence how we interpret images. For this issue, we called on the Photography+ community to contribute images inspired by the theme of Photography and Power. Under Surveillance by Thero Makepe was chosen as the featured submission, accompanied by a written piece.

Who holds the camera? Who is being watched? Who gets to be visible, and who remains in the margins? We are not asking whether photography is political. That much is already evident. The question is: whose power does it serve now? And how can it be reclaimed?

Amin Yousefi

Editor