From issue: #17 The Graduate Issue 2022

written by Sabrina Citra

To photograph is to capture (y)our world. In her seminal text On Photography, Susan Sontag writes that the act of photography is a form of appropriation, that through creation the photographer establishes a certain relation to their subject, which puts ‘oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge – and therefore, like power’. The photographer produces a given reality that viewers consume when they look at the images. They allow the photographer’s gaze to form their own, and in doing so become immersed in the image-maker’s view of reality.

Vera Yijun Zhou plays with this aspect of photography in her work Hang the Pig. Using the gaming engine Unity 3D, she built a dehumanised, image-based world that imagines a pig’s gaze, with photographs parcelled onto virtual screens and billboards. In these images, Zhou transmogrifies human flesh into meat, labelling it in sections to mimic a butcher’s display. Zhou interrogates the negative representations associated with the image of the pig by asking, ‘How does a pig look at screens in a pig’s world?’ and ‘Would pigs be offended by pork images on social media?’ The queasy mix of the familiar and the strange is further evoked by a short story she wrote to accompany her installation, titled Nice Meating You.

Austin Cullen embarked on a similar conceptual journey in A Natural History (Built to be Seen), which questions the representation of the environment in North American natural history museums. His photographs serve as windows into the exhibition process, capturing both the display of the ‘natural world’ through dioramas and miniaturised landscapes, and the cultural construction thereof. Cullen’s monochrome images place us at a remove from the scenes he photographs, and he blurs the boundaries between the carefully staged displays and behind-the-scenes views usually available only to museum staff. In doing so, he highlights these museums’ dramatisations, encouraging us to reflect on our own relationship with what we have been taught about what’s ‘natural’.

Erin Lee’s work also encourages viewers to question commonly accepted narratives. Through her series The Crimson Thread, which interrogates Australia’s colonial past, she hopes ‘to question official histories and to consider how strongly our past still exists in the present’. Her work takes its lead from the 1954 royal tour of Australia led by Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh and, using a wide range of photographic subjects from Aboriginal landscapes to portraits of priests, Lee showcases how white privilege has permeated throughout various aspects of Australian life. Inviting the viewer to speculate on the imperialist gaze, she demonstrates how embedded whiteness is in the construction of Australian identity

Zhou, Cullen, and Lee all question the so-called ‘objective’ gaze, either by showcasing its limitations or by demonstrating other ways of looking. This is a key interest in contemporary photography (and society). It suggests a duality within the labour of photography, a responsibility to honour and accept one’s own perspective while ostensibly looking out to the world. For the viewer, recognising the photographer’s craft can offer an insight into their subjectivity, and with it our own.

That’s an interesting way to consider Anna Sellen’s work Drip by drip, we are fed with concrete, which was partly made in response to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Centring her own family’s history in the Soviet Union, Sellen used augmented-reality technology to create a digital exhibition that explored personal and collective memories of the Cold War. The exhibition was constructed in a concrete bunker, and invited viewers to familiarise themselves with surroundings Sellen’s family knew only too well. Her family’s archival portraits were placed in the bunker, allowing its material reality, the debris, concrete, cement, to speak for itself.

Victoria Ruiz’s El Carnaval Que No Pasó presents a similarly embodied history, a reimagining of Venezuela’s fraught recent history which is based on lived experience. Ruiz uses surreal and carnivalesque elements to symbolise the failure of the Venezuelan dream in the wake of Hugo Chávez, with her images depicting a battle sequence set against brightly coloured backgrounds. Citizens are identified with their ‘flower skin’ costumes, representing the hope that they carried for the nation. The force of authority, ‘La Represión’, is draped in black. In the peak of battle, the citizens’ costumes change, coloured lines now mimicking the paths of the bullets entering their bodies. By using the iconography of Venezuelan culture, Ruiz showcases both the intimacy of her experience and her grief for her nation.

Jana Islinger takes a straighter, more documentary approach to relay a story overlooked in mainstream Western media. In Dora – Georgia on the move, she highlights the ambivalence experienced by many Georgians, who lie between ‘the dream about Europe, the fear of Russia and the consequences from years of oppression’. Her photographs document spaces of sanctuary, such as sanatoriums, refugee camps and churches, sought out by Georgians ‘struggling under capitalism’ in post-independence Georgia or seeking refuge from the Russo-Georgian War.

Islinger, Sellen and Ruiz highlight the magnitude of displacement that can result both within and across national borders, and convey how place can affect one’s perception of self. Mexican photographer RoN, who has asked to remain anonymous, references something similar in the observation, ‘No one can remain untouched by their surroundings.’ In his series Seasonal Worker, RoN uses photography as a mode of connection with his past self while working as a ‘trimmigrant’ harvesting cannabis in northern California. Through a mix of monochromatic and colour photographs, RoN records his labour but also moments of joy, such as adventures on beaches or with friends. The arrangement of images allows him a moment of solitude in the present, to ‘converse with myself, to remain present’.

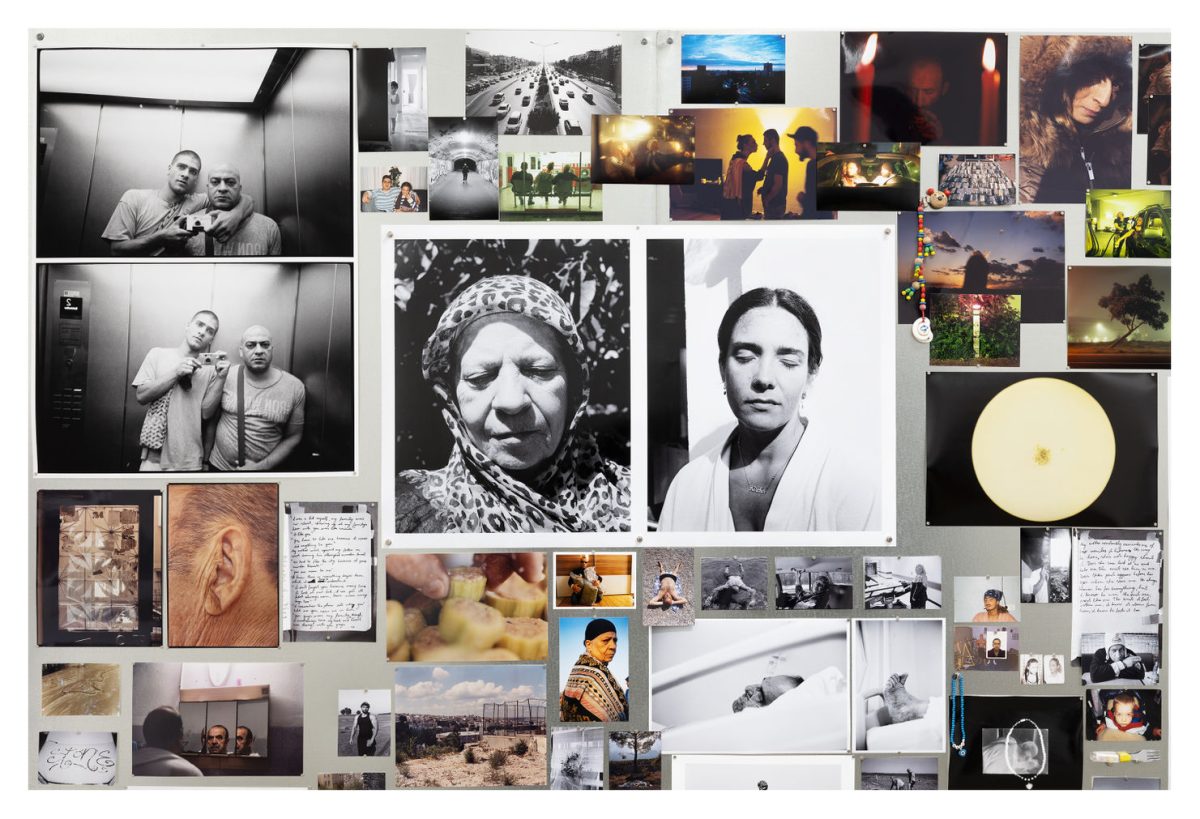

Abdulhamid Kircher shares a similar sentiment in his series Rotting from Within, which helped him begin to understand his father. The work is made of both archival and new photographs depicting his father’s life, including images of Abdulhamid’s mother and grandparents and his father’s girlfriend. The photographs were presented as a constellation in which ‘all the images burst out of this one larger image [Kircher’s only picture of him as a baby with his father] and feel like a scattering of memories’. Kircher purposely leaves certain moments out of sight, grappling with the complex challenge of ‘painting an accurate picture of a person while shining a spotlight onto them with images’.

Ali Mohamed brings his own experience to bear on his images of young British Muslims in Unseen. Focusing on young people who feel – as he did – that they don’t fit into mainstream Islamic culture, Mohamed photographs them in clothes they have chosen, in a bid to document how they’ve adapted to their community, or vice versa. In five of the images Ali introduces Fahmida and Seny; the remaining photographs depict people who preferred to remain anonymous, their faces concealed behind gold leaf. Unseen thus helps provide visibility to people often overlooked by the British public, and questions notions of inclusivity.

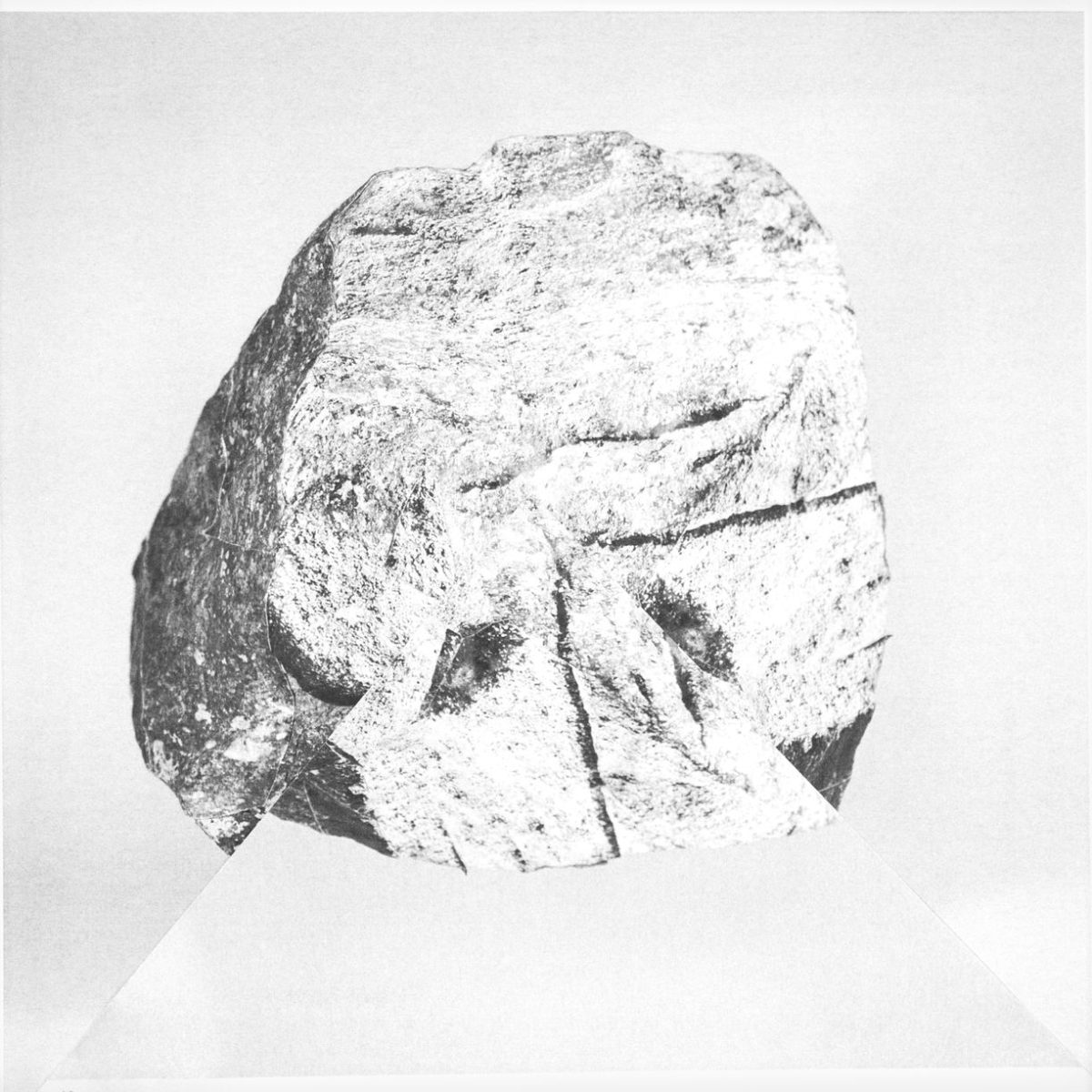

Using twenty-four carat gold also confers a value to Mohamed’s subjects, a dynamic beyond the surface of the photograph. That’s something that Ruben Storey has played with too, in his series Gwandra, which means ‘to ramble’ in Cornish. Gwandra is intended as an interrogation of form – specifically of granite found in Penwith in Cornwall. Storey draws on found objects, photographic reproductions, land art, and the St Ives School of Art to make collages and physical photographic sculptures, challenging the materiality of photography rather than accepting it unquestioningly.

The 2022 Graduate Issue draws attention to a diverse array of positionalities, suggesting that photographs are indeed packages of many realities. But the lines of view are expanded beyond distant witnesses to include personal and even painful reflections. In viewing them we too are invited to interrogate, question and reflect, alongside the makers of these many worlds.

Thanks to Spectrum Photographic, Photoworks’ official print partner