Queer History Now is an LGBTQ+ youth group dedicated to responding to queer histories through heritage and creative skills. The collective has brought together young people with different interests and backgrounds who have developed a shared ethos for encountering, producing and challenging queer history.

The group built a visual language using a broad range of creative processes including collage, mixed media, digital tools and needlework, expressing creatively how queer histories resonate with a present queer experience.

Given the current guidelines, this programme was delivered digitally and fostered rich discussions as we managed to harness a safe space, energy, honesty and sharing lived experience. However, we decided to honour this aesthetic and document our journey through screenshots, chats, gifs and Zoom calls which became our new normal, using the digital screen as a conduit for being together.

This page includes captions that unpick the artists’ final creative outcomes, their working methods and responses, intertwined with documentation from the programme and responses to the creative exercises throughout.

‘Our Existence is Inherently Political’ From the Queer History Now Manifesto Recorded by Ellie Turner Kilburn

Resist the linear! Our history is an endless sticky cobweb! We fill in the gaps ourselves! We stitch ourselves into their past(s)! You change the story every time you tell it! No matter how tightly we weave it, it will never quite match up! I never met Tommie, or Betty! My own memories will someday escape me! Lavender essential oil may help you sleep!

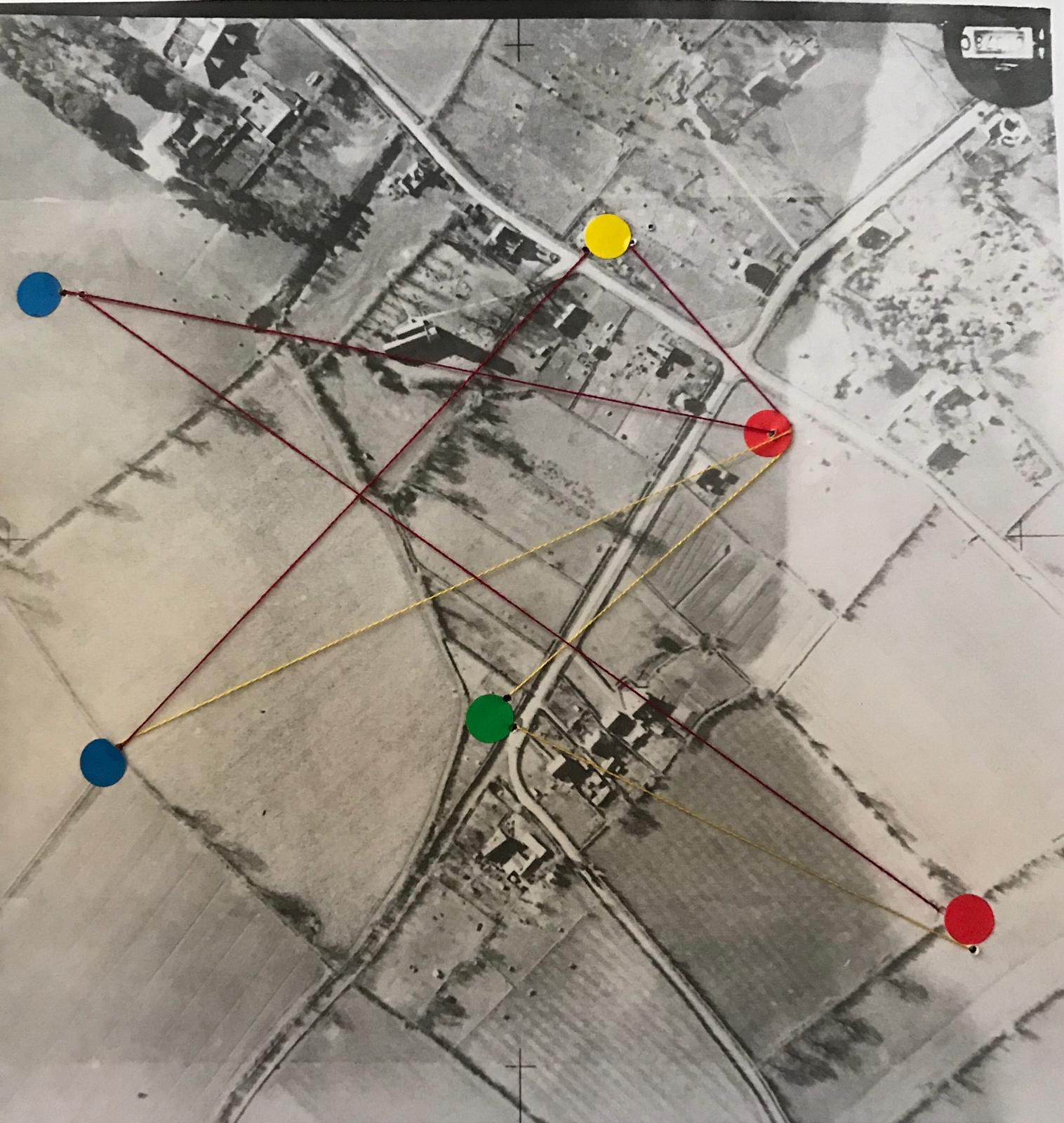

In the images that I’ve created over the course of the project I’ve been particularly interested in the ways that we interact with history, and what we do when we encounter history, what we do with it and where it goes. By photographing and then collaging and rephotographing images from the Tommy & Betty archive I’ve tried to explore the ways that we find and then reframe history, constantly applying our own lens to it. By incorporating these images with images from my own life and experiences with the project I’ve tried to explore how our lives interact and intersect with history, and that often the lines between what is objective history, and what is our own interpretation of history can blur.

Hannah O’Gorman

As part of the group’s outcomes, Queer History Now were invited to create a Manifesto about they way they’ve worked during this project, their ambitions of how they want archives to be used and shared, and what they hope to see in the sector in the coming years with regards to talking, sharing and learning about our histories. This Manifesto is part of the Photoworks ‘Festival In A Box’.

‘Representation must breed representation’ From the Queer History Now Manifesto Recorded by Reuben Davidson

When I scribbled over Tommy & Betty and company marching along the promenade, I was thinking of the ways that photos such as this one made me feel alienated from them, because of the value they clearly put on being a part of the military, which anonymises them and doesn’t celebrate their queerness. But photos like the one of Tommy & Betty and friends lounging on the beach spark instant familiarity; I can see in them my friends hanging out together.

A book of mormon, a necklace given to my partner, and a picture of my mother. I’m interested in the intersection where faith and queerness meet. It captures the specific parts of my life that I wouldn’t want to archive, yet it is my experience.

The temporality of the images we’ve been working with have been very powerful for queer history and queer lives. I wanted to connect two moments in time by reclaiming a march I took part in Brighton and situating them next to the Tommy & Betty march.

Top left: ‘This collection of memorabilia and images tracing two women’s lives together was found and saved by complete chance, it documents a life of adventure shared by Betty & Tommy’ E.J Scott

E.J. Scott led our first session introducing the group to the Tommy & Betty archive,. This collection was included in the Queer the Pier exhibition at Brighton Museum & Art Gallery which E.J. Scott was involved in curating.

Two members of the group; Adrian Devany and Janet Jones collaborated on an Instagram takeover, with Adrian uploading stories which traced Janet’s personal, social and political life.

In Adrian’s words: ‘Get ready for a little queer history!’

Jamie Brett from Youth Club Archive facilitated two sessions with us; the first looking at how to diversify archives and the other about how to use and conserve digital archives. QHN member, Ellie, wrote a piece about archiving online as a response to Jamie’s inspiring session. Learn more about Youth Club and what we covered here.

Look at me! Looking at you! Looking at me! What a space we are building! One day, the sun came out during a meeting, and everyone in the zoom call began to glow!

Creative outcome ideas 2020, Liam Croot

Regarding the objective of creating a response to the Tommy & Betty collection, I feel strongly that the response I’m most passionate about making is one that actually addresses the ethical concerns of putting the private belongings of the queer and recently deceased on public display without obtaining their consent, with particular regard to the potential implications of those depicted in the photos that are still alive, issues of consent, privacy, anonymity, and the “heterosexual gaze”.

Ideas for this response include: Intimate photos of modern queer life with identities obscured This response would not be exhibited alongside the Tommy & Betty collection, and perhaps not even refer to it by name, rather stating “This work is a response to the exhibition of a collection of private objects of a deceased LGBTQ+ couple who lived in a time where being openly gay was less accepted, and the implications that putting said objects on public display has on queer people today.” (i.e. reinforces that we are still kind of something to gawp at but not really)

My home is a museum and I am a very prolific magpie! My museum is queer in form, methodology, and content! My museum is a butch and a cat and I love them both! Treasure what you still remember! Commemorate what you don’t! Make room for Tommie and Betty! Archive every fraying thread of your life!

Reflections, Adrian Devany

My creative responses can be considered an archive of our collaborative work: of trying to make peace with the struggling, sticky cobweb of our communal history. Working through photos of my own life alongside those of Betty and Tommie’s, I tried to celebrate the messiest parts of our methodology as queer historians: the fallibility of human memory and ever-mutating oral histories; the way we projected ourselves into the history of two people we had never met; and rejecting empirical truth-telling to understand two lives that, in order to be lived, could not be named. When museums neglect us, we build archives in our own homes, and accept that our artefacts may fade, age, and someday perhaps be sold in an auction and become the subject of an art project by a youth group. And when we build these new museums – in photo albums, in living rooms, in lifelong partnerships, and in Zoom calls during a pandemic – we build them on our own terms, for each other’s eyes only, for now (and maybe not forever!), and along every struggling, sticky thread of that cobweb.