From issue: #12 Time

By Raquel Villar-Pérez, Photoworks

TW // Please note, this article contains references to sexual violence.

How can someone start to make sense of a socio-political and cultural context in which their body is read, but the context itself is so alien to them because, in fact, they never belonged? What is it to be given an identity that is at the same time being overwritten by your actual environment? El Jardin de Senderos que se Bifurcan (The Garden of Forking Paths), borrows the title and the parable strategy – a literary resource to tell stories – from the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges. It is the exploration of imagined stories and the multiplicity of possible parallel narratives of oneself.

Tarrah Krajnak was born in Lima, Perú, in 1979, in the lead up to the bloodiest armed conflict the country ever witnessed since colonisation and that started in 1980 by the group known as Sendero Luminoso. Two consecutive military dictatorships, an uneven industrialisation that forced major migratory movements from the Andean and Amazonian region to the coastal cities, and a severe economic crisis facilitated a fragile political system. But Krajnak only read about this history. She was born an orphan, the result of a sexual violation and was then given up for adoption to a North American transracial couple. Returning to Perú for the first time thirty years later. For the past 11 years, the artist has relied on photography and text as the mediums that bring her closer not only to her native Perú but also to her given indigenous identity.

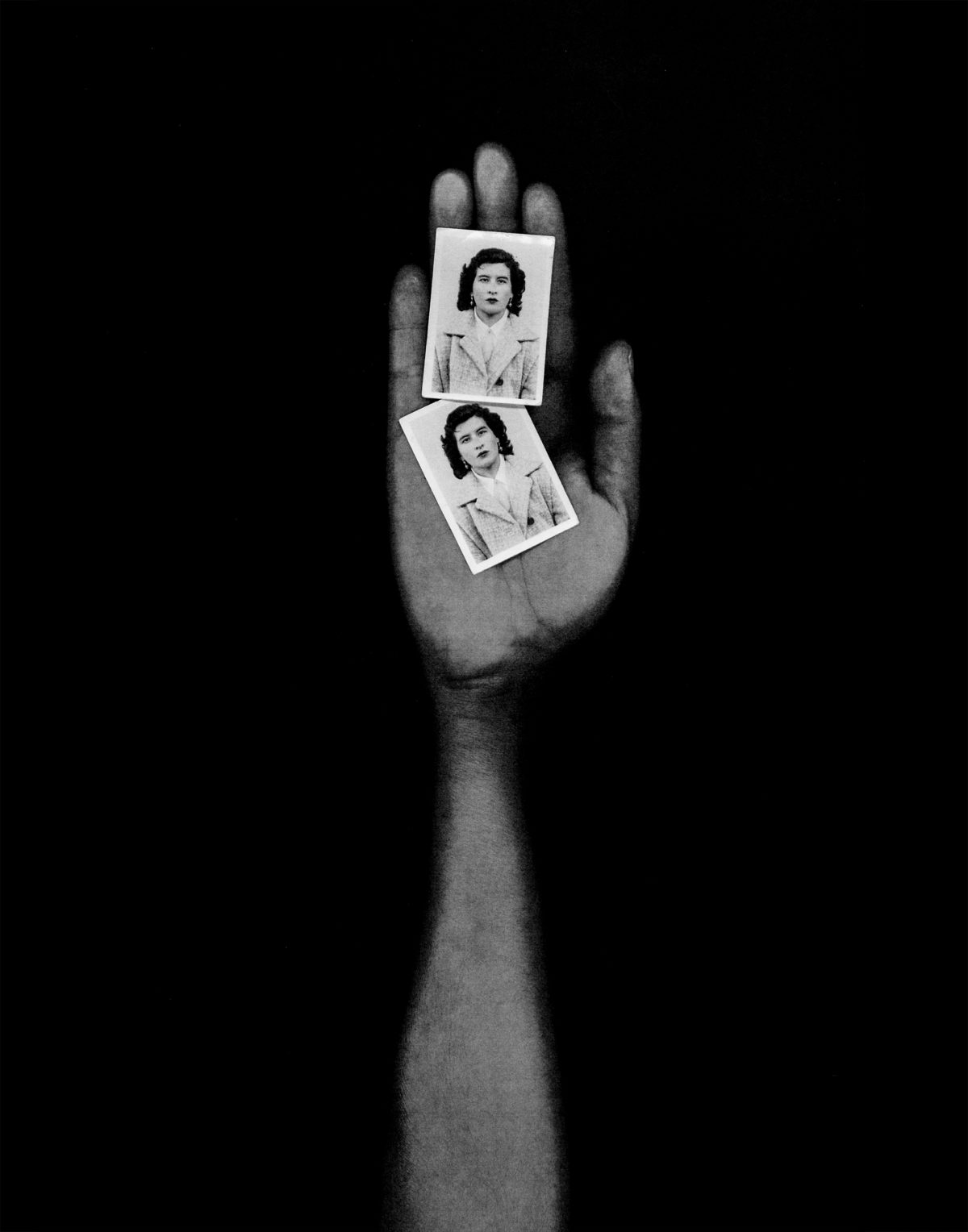

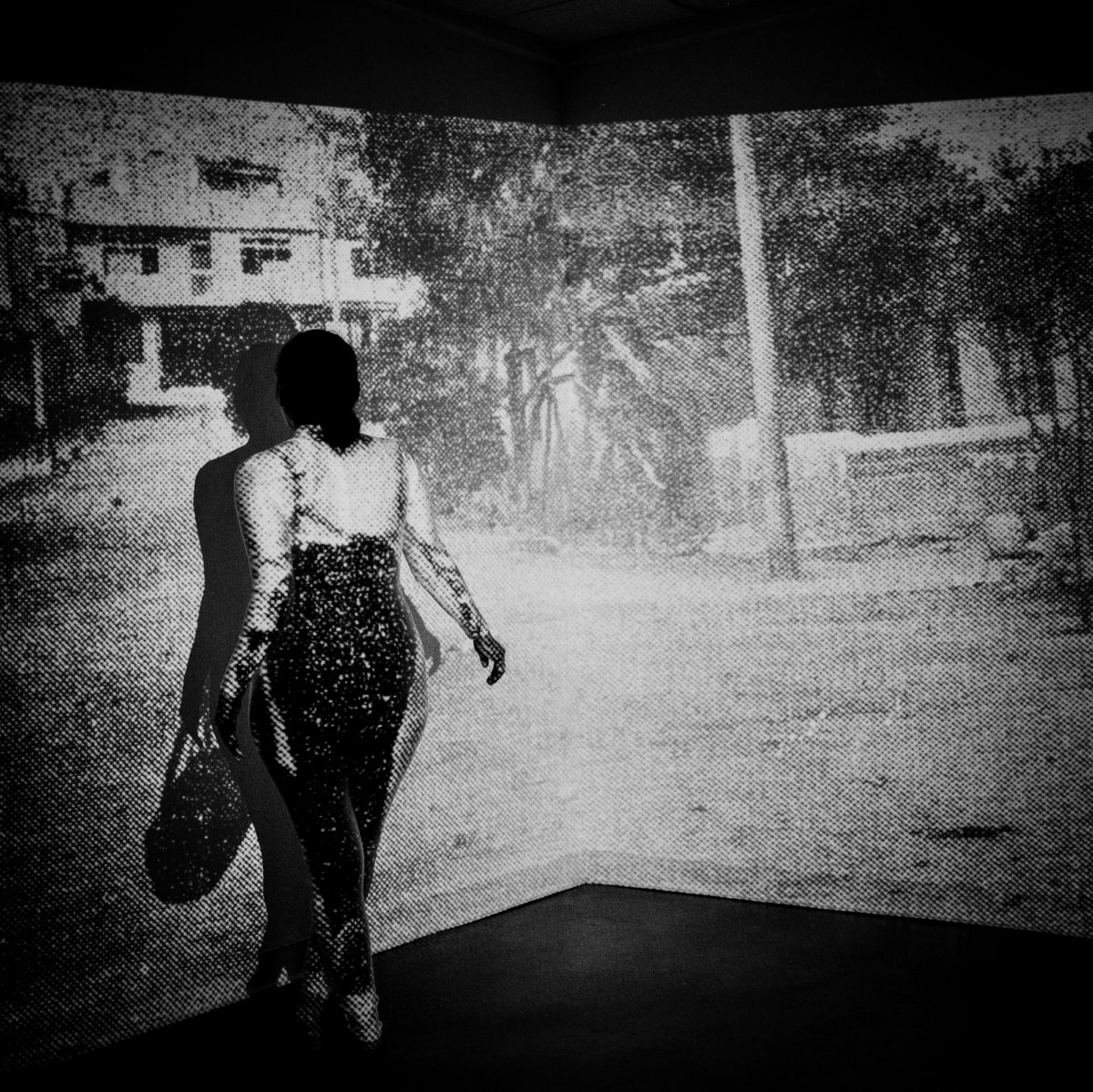

Krajnak restricts the colour palette to a warm timeless cream and black, putting the spectator in a comfortable mental space of sorts; yet the images and texts that follow soon alter the climate to one of tension and unease. The project is composed by seemingly disjointed sections displaying re-photographed ID photographs of unfamiliar women, images of an envelope with a name and a date on it, the photograph of a baby goat conjoined faces, a dog lying on the ground, the missing photograph of a pyramid, the disturbing sequence of a woman walking away from the audience, and more. Functioning as visual and textual parables, as in Borges, these strategies permeate the project with confusion and uncertainty, referencing the non-linear and difficult to articulate story of the artist based on a recollection of inconsistencies and disagreements.

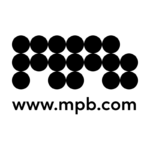

To begin to imagine her potential history, Krajnak gathers and photographs the stories and memories of other women born in 1979, and also the stories and photographs she found in the orphanage where she was born. Performativity is a crucial element to her practice; the artist embeds herself in the black and white projected photographs of the women her age re-enacting their stories, and also in the archival images, in a gesture to own these histories and memories. The resulting grainy-analogic-quality photographs, purpose-made or refashioned from old found material, add to the set of disorienting games at stake in this project. These images emphasize the punctum or ability to defeat the time(ness) in them as per Barthes, and also so does the ritualistic process of re-photographing the found photographs and juxtaposing them in the present.1 Serving as real or fictitious time capsules, they enable the artist to reflect on the traumas of violence and war that are unaddressed and in particular, that of rape.

The final Report of Truth and Reconciliation made in Perú as an evaluation of the armed conflict and published in August 2003, confirmed that uncountable acts of sexual violence against women were committed by the State and also various guerrilla groups for over 20 years. However, sexual violence was considered collateral damage to the many violations of human rights infringed during the conflict.2 Because of the associations with the victims’ sense of humiliation and shame, these perpetrations generally go undocumented. In her seminal book The Civil Contract of Photography3, the scholar Ariella Aïsha Azoulay wonders if anyone has ever seen a photograph of a rape? and in her analysis of World War II, she reveals that in spite of being highly attracted to areas of conflict and violence, photographers clearly choose not to photograph rape, making them accomplice of silencing the trauma.4

Personal dreams also inform Krajnak’s El Jardin de Senderos que se Bifurca. Ultimately, it is an abstract visual meditation on time and temporalities, the arbitrariness of representation, the versatility of truth in the absence of memories, and the fragility of the existing ones.

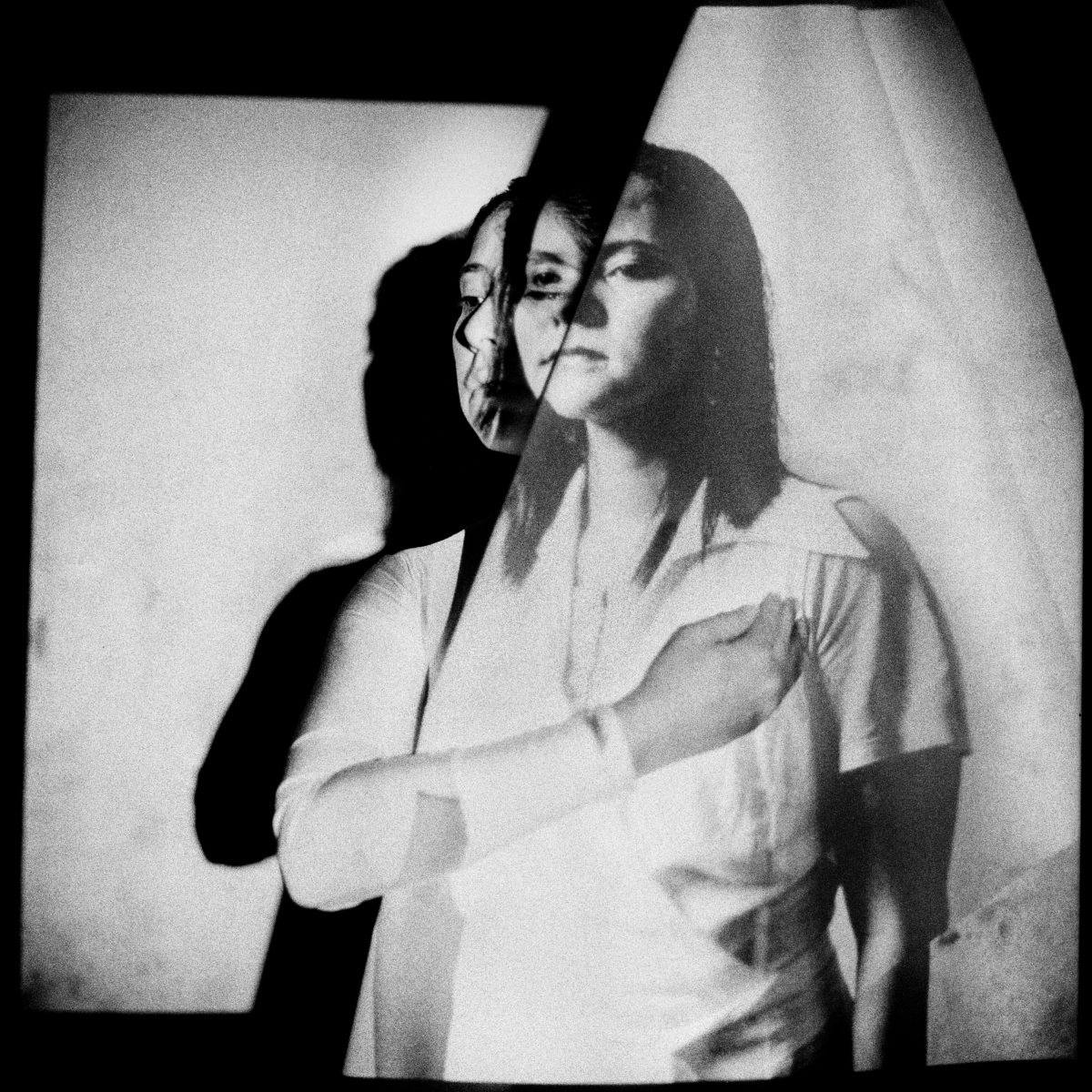

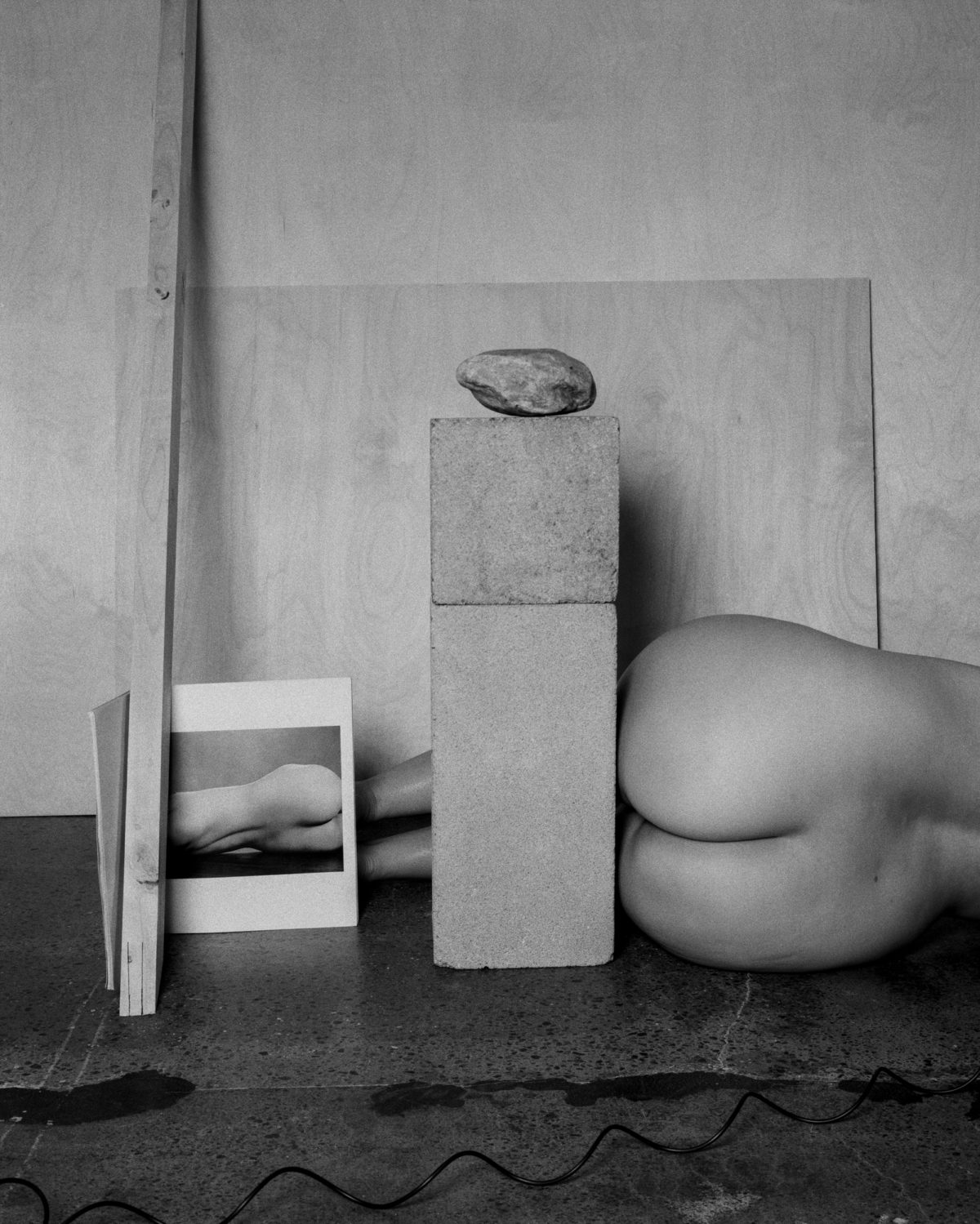

Tarrah Krajnak works on several projects at the same time and not all of them have such depth and investigative diligence. In her project Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes the artists re-enacts Edward Weston’s iconic nude studies. As a brown woman, she makes a playful, yet critical commentary on the canonical white male gaze in photography. Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes has been shortlisted for the Louis Roederer Discovery Awards and will be exhibited at the Rencontre d’Arles 2021.

Photography+ is supported by MPB.