There are countless ways to define a good photograph, and for many digital imaging scientists like me, there are many purely quantitative criteria against which to make that assessment.

Typical metrics in our field have complex-sounding names like signal-to-noise ratio, modulation transfer function, and scene entropy; such metrics can be mathematically calculated, and so in some ways a “good photograph” to be defined numerically.

In some realms of photography, like digital imaging on NASA space missions since the 1970s, the values of those mathematical metrics can often matter more than the content. For example, when a space probe is flying past some planet or moon or asteroid or comet there’s often no choice about composing or framing an image, or about making any of the other kinds of artistic or aesthetic choices that “normal” photographers typically make when shooting. The laws of gravity and the physics of spacecraft trajectories often dictate the lighting conditions, as well as the amount of time spent with the subject. The goal in many situations like that has been to just take as many photos as possible, as the probe zips past at high speed. A good photograph under such conditions might be any photograph, then, without saturated or underexposed pixels or blurring of the scene, that can be successfully radioed back to Earth. Even the scene content might be a surprise (which is of course often where the fun and the science are).

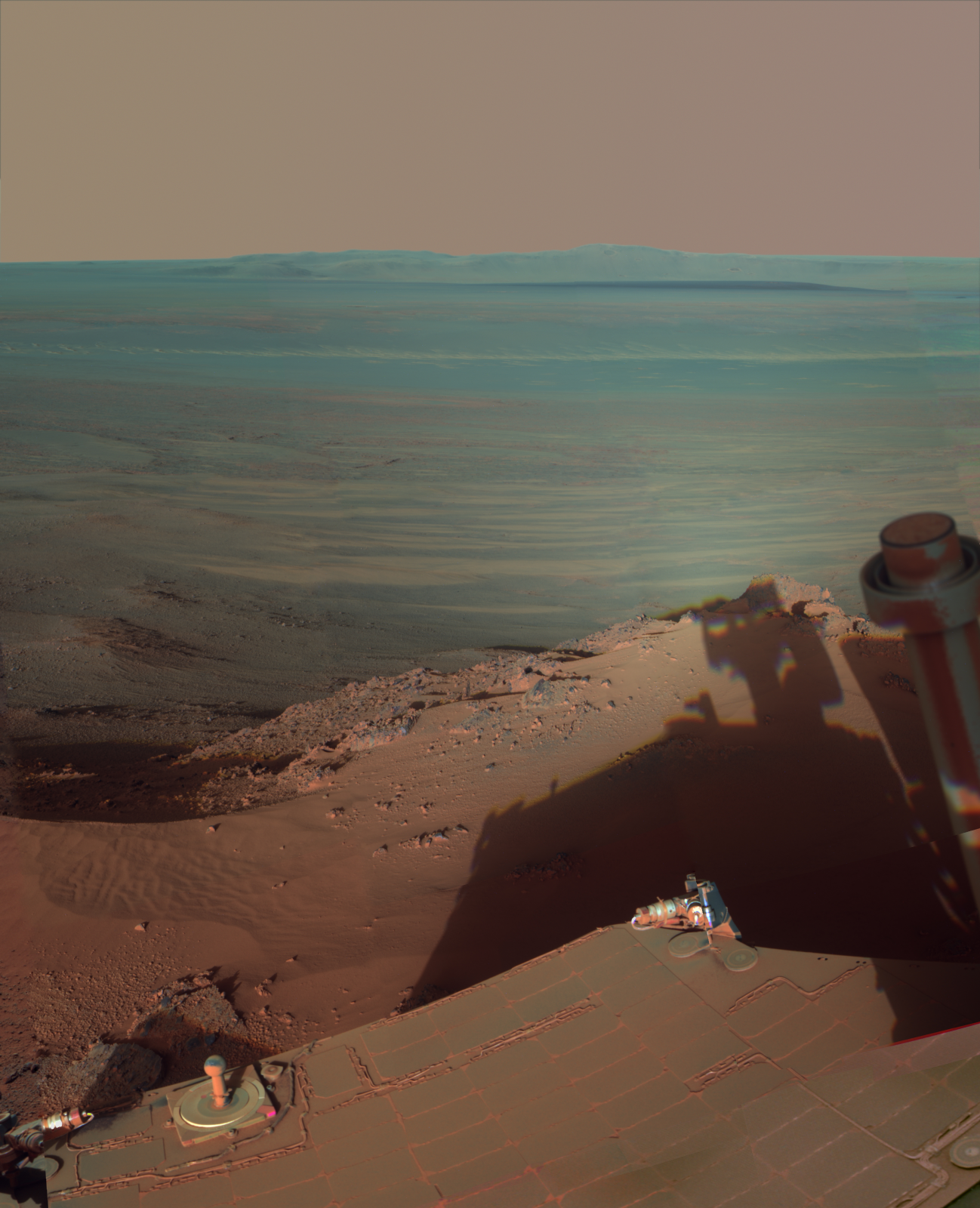

More recently, however, some of my colleagues and I involved with digital space imaging have had the chance–no, the luxury–of much more time devoted to picture taking, much more bandwidth for sending pictures back to Earth, and better resolution of our cameras compared to earlier missions. These advantages have allowed us to not just “acquire images,” but to be photographers–artists–while at the same time gathering all of the needed scientific and engineering information from the missions. Spectacular recent examples of this kind of modern outer space landscape photography have come from the NASA Mars Exploration Rovers rovers Spirit and Opportunity , the Mars Science Laboratory rover Curiosity, the Cassini orbiter around Saturn, and the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter around the Moon. When I am designing a camera sequence for the color cameras on the Mars rovers, for example, I can think about many of the same kinds of issues that landscape photographers consider in their quest to capture the spirit and stories of their subjects. How can we frame this particular shot? What time of day is best to capture this scene? Can we include some foreground rover parts in the image to give the view a sense of depth and scale? What is the balance of sky and ground? Do we view the scene in natural light and color or with enhancing false color filters? And how do we interpret the view later, in the computer “darkroom” where we process the images?

I was into black and white landscape photography when I was a kid. My parents bought me a Pentax 35mm SLR camera and I spent a lot of time shooting the outdoors and developing prints with my friends in the high school photo club. I was fascinated with the interplay of light and shadow in the environment, with the way a photograph could be framed and composed, like a musical piece, to tell a story to the viewer in a certain way. I went to the library and soaked up Marcel Minnaert’s book The Nature of Light and Colour in the Open Air and checked out picture books about 19th century landscape photographers like Edward Weston, Timothy O’Sullivan, and William Henry Jackson, and 20th century ones like the master Ansel Adams. When I figured out how to hook up my camera to my telescope, I was hooked. Space was the ultimate landscape, and that’s when I knew that I wanted to get into astronomy and space exploration. I never imagined that I’d be helping to take photos with cameras on other planets, though!

Of course there is an enormous amount of technical engineering and computer work that goes into building, launching, and operating these missions, building and calibrating the cameras, and taking the photographs. Teams of hundreds to thousands of incredibly talented and creative scientists and engineers are needed to make these modern voyages of exploration possible. However, the artistic, aesthetic–photographic–aspects of many of the final photos that are created can, in the end, reflect individual choices by an individual scientist or analyst about how to represent their subjects. What makes a good photograph, then, often comes down to a choice between whether that representation is based on specific scientific needs versus a simple desire to capture the wonder and drama of truly alien vistas. Indeed, the relation to reality that all art must bear is a particularly strange one for space-based landscape photography. It’s not quite abstract art, but it also isn’t a reality that any human has quite witnessed yet either.

I was trained as a scientist but I’ve come back to my roots in many ways and become a space landscape photographer. In fact, many of us involved with cameras photographing Mars, the Moon, Saturn, and countless other destinations in our Solar system and beyond have had the good fortune to be able to consider, now and then, the artistic aspects of our work.

Published on 17 June 2013

Commissioned by Photoworks

Parts of this article are based on Dr Jim Bell’s Postcard’s from Mars (Dutton, 2006)