From issue: #21 Thingification

If photography can trace back its roots to the 15th century, it’s the materialisation of a particular way of seeing linked with objectification and colonisation. But artists working with images have pushed back, and Photoworks Annual #30 The Thing includes 27 such projects plus essays and texts. Diane Smyth, Photoworks Editor, explains more

‘Imagine that photography does not have its origins in the invention of the device, but rather in 1492,’ writes Ariella Aïsha Azoulay in Toward the Abolition of Photography’s Imperial Rights (Azoulay, 2021, p27). Her idea sounds counterintuitive, but it suggests a way to unpick the cultural conditions which produced photography and which, she argues, still underpin it.

1492 marks the year Christopher Columbus ‘discovered’ the Americas, a key date in the so-called Age of Discovery and the start of Europe’s major colonial exploits. The word ‘discovery’ is revealing, implying a particular gaze as the central or only perspective, and the right of that gaze to look. Azoulay references ‘imperialism’s scopic regime’ in the same essay (Azoulay, 2021, p47) and elsewhere writes of ‘the invention of imperial rights – the right to discover, uncover, penetrate, scrutinise, copy and appropriate – thus erasing (like the operation of the shutter) how appropriated objects (which made up the centre of gravity of universal rights) were in fact plundered and in effect how the discoverer violated others’ rights’ (Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism, Azoulay, 2019, Section 1, p97-103).

For Azoulay, photography draws on and neatly mirrors an imperial logic. ‘Single photographs cut slices out of a wider world,’ she writes (Azoulay, 2021, p28); photography is ‘part and parcel of an imperial world, that is, the transformation of others and their modes of being into lucrative primary resources, the products of which can be owned as private property’ (ibid). Both imperialism and photography draw on an imperial temporality, that’s to say, which allows people ‘to believe, experience and describe interconnected things as if they were separate’ (Verso blog, Azoulay, 2018). Azoulay describes a worldview in which a holistic continuum can be perceived in terms of things, which can then be used as resources or commodities.

In doing so Azoulay is aligned with others, with researchers such as Martin Jay who conceived of vision as culturally as well as physically constructed, and who spoke of ‘scopic regimes’ in his 1988 essay Scopic Regimes of Modernity. Jay also locates a shift in the 15th century, writing of the development of perspective in painting, and a particular way of organising visual information from a single position to a vanishing point. In this shift, which he identifies with Norman Bryson’s ‘’Founding Perception’ of the Cartesian perspectivalist tradition’ (Jay, 1988, p7), the viewer is separated from a world arranged before him or her, and placed as a single gaze at the centre of the universe. He or she is set up as a dispassionate observer, and what’s seen is detached from a wider context or narrative.

Jay writes that this scopic regime is ‘in league with a scientific world view’ and points out that it’s not always bad, describing the ‘practically useful fiction of a distanciating vision’ (discussion following Scopic Regimes, Jay, 1988, p25). But he emphasises that it’s a fiction, one possible regime among many, and a fiction that has also brought dangers. From the 15th century on this gaze was associated with the wealthy, white, Western men who developed it – people could look with scant regard for what they saw, and little care for its perspective or opinion. This hierarchy of seeing is also intrinsic to the whole operation, to the ‘distanciating vision’ which suggests a world there for the taking.

In Photoworks Annual #30, we take this radical reading of photography as a starting point. Titled The Thing, following Aimé Césaire “colonisation = thingification” (Discourse on Colonialism, 2001, p42), it considers how photography has been used to ‘thingify’ what it shows and how artists have pushed back against that. The Thing draws together 27 projects from around the world, which centre on issues such as racism, sexism, LGBTQ activism, worker rights, immigration, and the environment. By looking at how each series tackles and de-stabilises photography, The Thing suggests these artists are also identifying a common problem, around photography and how it pictures the world.

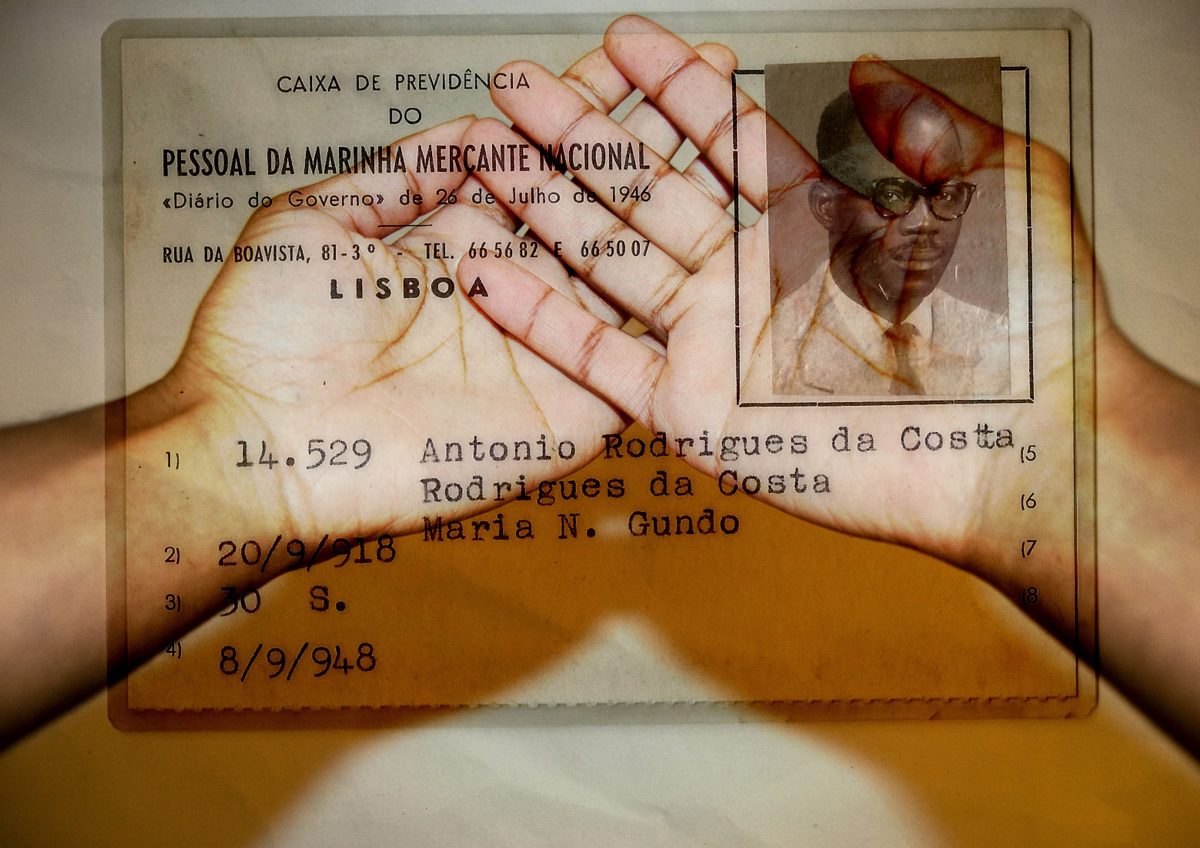

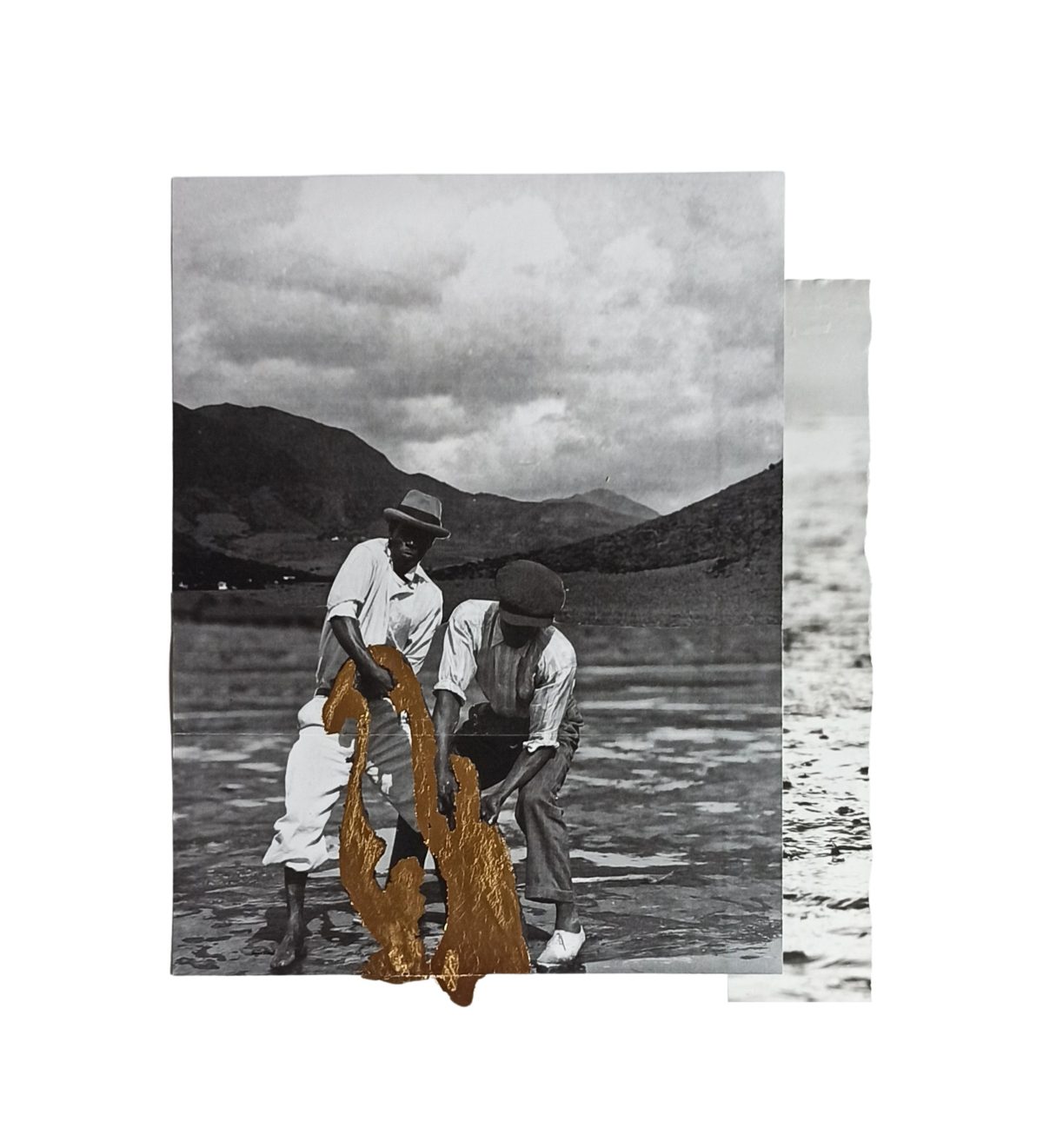

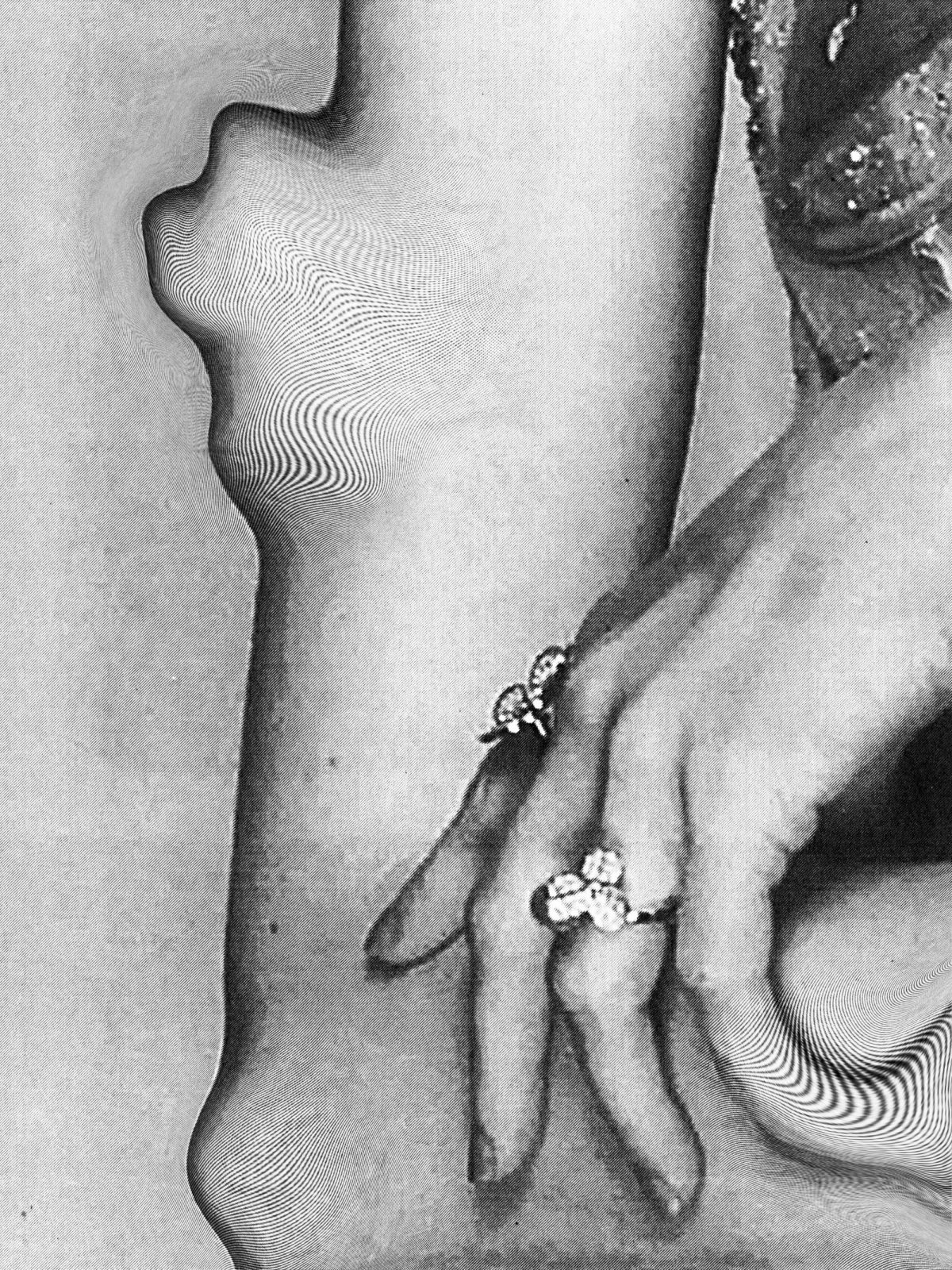

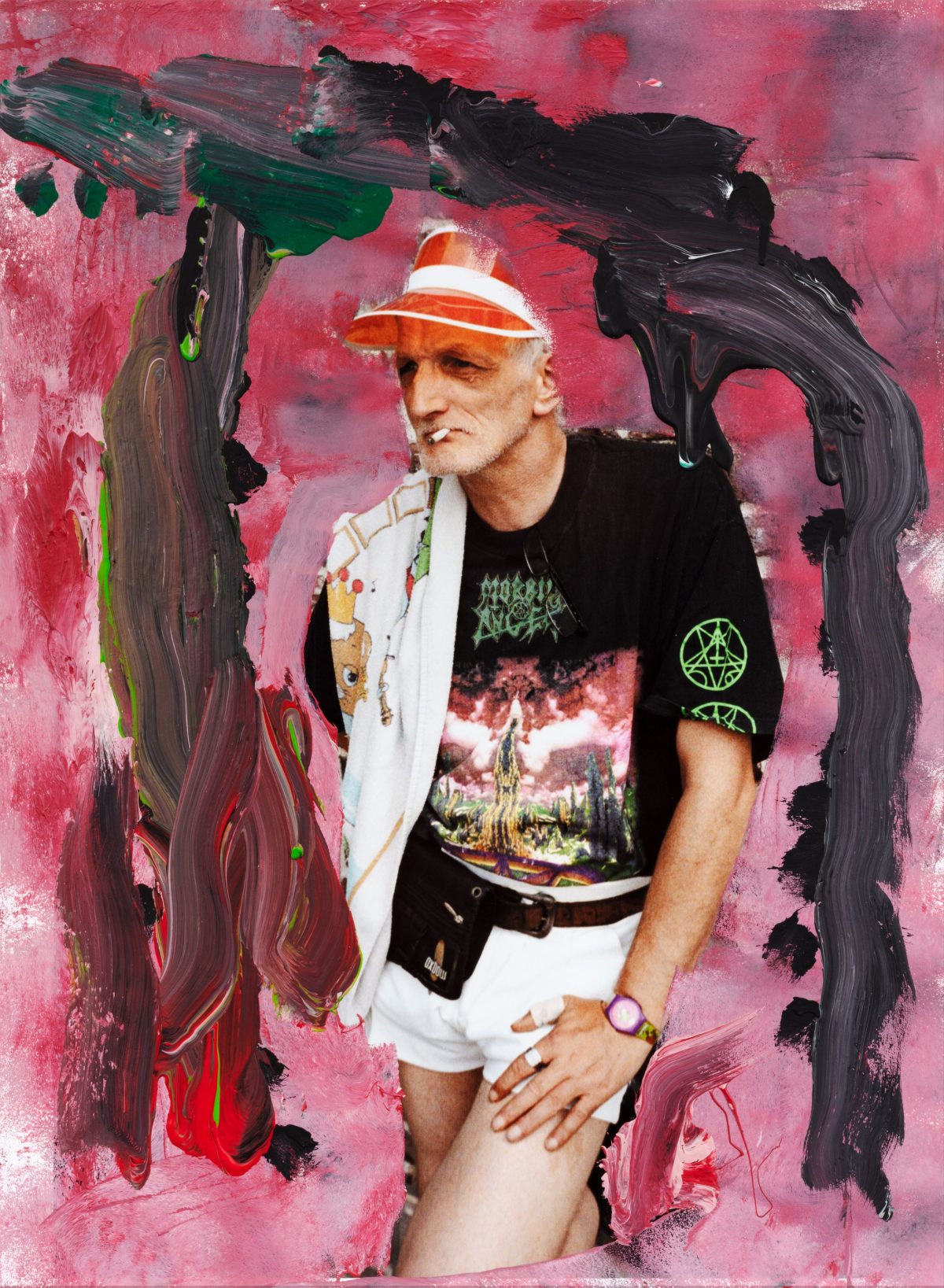

The Thing includes collages by Giana De Dier, for example, taken from her series Utopías decoloniales (2021), which combines her own family’s records with photographs from colonial-era archives fetishising the Black body and obscuring the female experience. Freeing the individuals depicted from their original representation, De Dier pictures them in abundant natural environments, controlling their own wealth and activities. Matilde Søes Rasmussen appropriates, distorts, and re-enacts photographs taken of her when she was modelling, meanwhile, in a series she titled Sue Me (2019) and describes as ‘a little revenge’ over a certain gaze made material via photography.

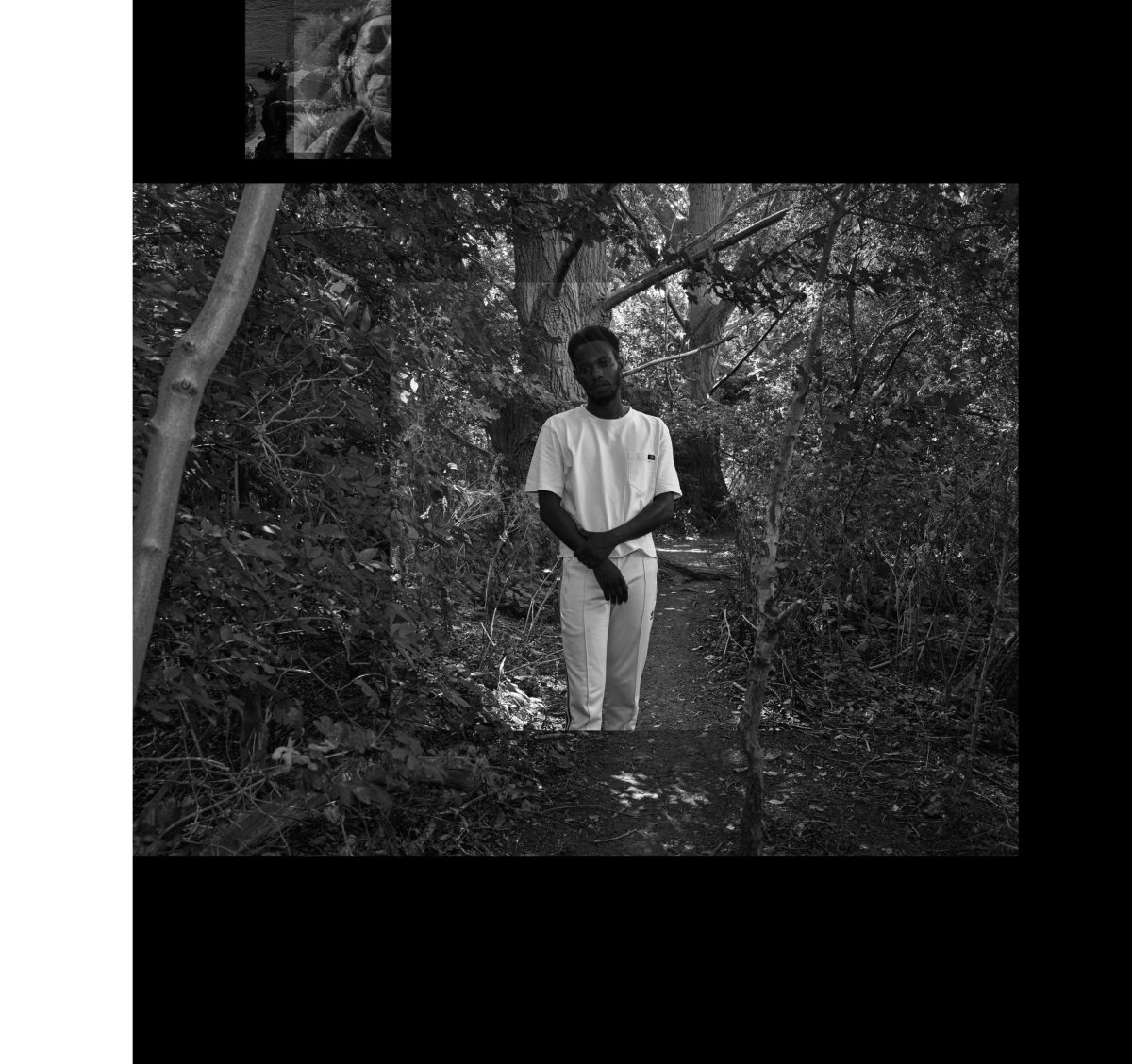

Meanwhile Jermaine Francis’s series A Storied Ground (2022) draws and subverts a painting tradition dating back to the 18th century, in which the environment is presented as an Arcadian landscape, owned and surveyed by the same wealthy white men who commissioned the painters. In Francis’ re-conception Black Britons are shown in similarly bucolic surroundings, with multiple images, double exposures, heavy black borders, and awkward crops deliberately disrupting the view. Observers can’t so easily survey people or the land, Francis’ series suggests. Vincen Beeckman’s La Deviniere (ongoing) suggests a similar rethink. Working with a group of people in a residential home, he takes their portraits them invites them to do what they will with the prints. One man rips up the images, another choses to paint over them altogether.

Remy Artiges quite literally blocks the view in BUG, meanwhile (2015 – ongoing). Dropping insects directly into his camera, he draws attention to them, to an apparatus we take for granted, and to a way of looking so familiar we now don’t perceive it. The latter is picked up by others, who consider the increasing prevalence of images and how this affects how we see the world and ourselves. Javier Hirschfeld Moreno’s series Profile (2020-23) combines 19th century cartes-de-visite with photographs found on Grindr and Tinder profiles, for example, showing both an early use of photography as self-presentation and its latter-day evolution. Cruising the dating apps is colloquially referred to as ‘window-shopping’ he says, and he finds it both irresistible and a kind of emotional capitalism.

Lauren Huret’s Praying for my haters (2019) considers content moderators employed in developing countries by social media giants, tasked with sorting through vast numbers of disturbing visuals to keep online spaces safe. ‘They are not cleaning,’ she comments, ‘they are maintaining a collective hallucination’. Other artists working on similar themes include Lucas Blalock, whose series I was wrong (2023) is an absurdist take on retouching, inspired by Bertold Brecht’s idea of theatre that reveals its techniques. Xiang Li’s The World of Daily Images (2023) considers the sheer number of photographs taken daily by his friends, meanwhile, and asks if this constitutes a colonisation of real life by images.

These artists’ works overlap and intersect in multifaceted ways, suggesting various insights into the same thing; many come from marginalised positions and communities, which is interesting but perhaps not surprising. Taking a look at a ‘distanciating vision’ which usually views without being seen, The Thing is a move towards studying ‘the colonizers rather than the colonized, the culture of power rather than the culture of the powerless, the culture of affluence rather than the culture of poverty’ (Laura Nader, Up the Anthropologist, p289). This exercise is best undertaken by those who know what it is to be thingified, as well as knowing about photography. The series and the contributed essays in The Thing each have slightly different insights into photography, power, and thingification and as such, they can say something working together.

This is an abridged version of The Thing, Diane Smyth’s introduction to Photoworks Annual #30 The Thing. The Thing is priced £35 and is available direct from Photoworks or via selected bookshops. Photoworks Friends receive a copy of the Annual and the Festival in a Box free, alongside a range of other benefits. Becoming a Photoworks Friend costs £35, and directly supports our programme and funds opportunities for artists.