From issue: #10 Care

Peter Watkins’s The Unforgetting has made the rounds, collecting praise and prizes along the way. It first was shown at Brighton Photo Fringe in 2014, then at the Format Photography Festival a year later, then at Amsterdam’s The Ravestijn Gallery, Liverpool’s Open Eye Gallery, and the Guernsey Photography Festival, all in 2016, and most recently at Webber Gallery, London, in 2017. During this time, Peter has twice been nominated for Foam’s Paul Huf Award (2014, 2016), shortlisted for the BJP International Photography Award (2014), and has won the Magnum Graduate Award (2016) and the Guernsey International Photography Competition (2016). Last year, the Skinnerboox Book Award saw the project made into book form.

Much, then, has been said, written, and indeed asked about The Unforgetting. That it ‘is a long-term exploration of trauma, loss, and shared familial memory’ (Paper Journal). That it ‘acknowledges the impossibility of ever fully articulating [his mother’s] absence’ while evoking ‘her continuing presence honestly’ (The Guardian). That it is a work of ‘equivocality, wavering between documents and invocations’ (American Suburb X), which ‘engages with some elemental questions about photography and the relationship between part and whole, form and expression’ (British Journal of Photography).

Peter and I are old friends, and as nice as it is for him to hear these things, they have come as mixed blessings, because of the very painful subject of the work. In some ways, I didn’t want him to have to talk about it anymore. So my own questions, I hoped, would allow him to reflect on the project and create a sense of distance from it, to tie up threads.

I was lucky enough to be with Peter when he started research for The Unforgetting in 2010. This conversation, which took place right before the pandemic, returned us to that beginning. But it was also a time, late 2019, that felt like a natural conclusion to the work – his grandmother, the family archivist, had just passed away; he was in the process of moving to Prague with his family; the book had recently been published. Not that closure is ultimately the point, as Peter suggests, but more a repositioning of oneself, forward-looking, ‘to some future place where the centrality of this trauma is moved aside.’

Oliver Shamlou, December 2020

Almost exactly ten years ago now – on 27th February 2010 – we were travelling through Belgium, along a very straight, very flat motorway. Can you say something about where we were heading and why we were going there?

We were headed to a place called Zandvoort in North Holland, a coastal town about 40km west of Amsterdam. I asked you to join me in visiting the place where my mother’’s body had been discovered in 1993, and we were driving there that day for the anniversary of her death. As we had little little to to no information to go by at the time, the idea was to take the ferry across from Dover, and head straight to Zandvoort, approximating the place where she would likely have entered the sea. I remember I got up before dawn the day after we arrived and attempted to do this, lugging camera equipment down to the beach. I was filming very slow, static, ordered shots. Everything looked grey on that trip, and the rain was frequent.

My sense with The Unforgetting is that you had to be very conscious of memory’s ordering, narrative-making tendencies when you were dealing with this extremely personal material. During the project did you have to kind of check yourself at times and say, ‘No, no, that’s not how it was; I’m I’m remembering it that way because …’’, etc?

I was certainly conscious, mistrustful even, of how memory can be transformed to narrative, especially so in its regurgitation. But I was thinking at the time about whether some memories have a kind of ‘purity’ about them, and others don’t. Not a sacred purity, but that somehow they live at the front of your brain and are so connected to a genuine sense of selfhood that they can be summoned at any moment – like those memories that seem so absolutely fixed, so important and symbolically central to the fabric of one’s being that they couldn’t possibly be subject to the same kinds of slippages of thought as the everyday misremembered stuff.

Against my better judgement, I do kind of believe that there’s a certain fixity to some aspects of memory, to the extent that this kind of memory can feel foundational and tapping into it seems to transgress the flow and linear perception of time – that it can sometimes feel more present than the present. But my work complicates this idea and seems to be saying that narrative construction in the familial processing of memory is inherent and necessary (if somewhat reductive), and that any portrayal that seeks out truth is altogether impossible, plagued as it is by inaccuracies and unconscious re-composition and reconciliation.

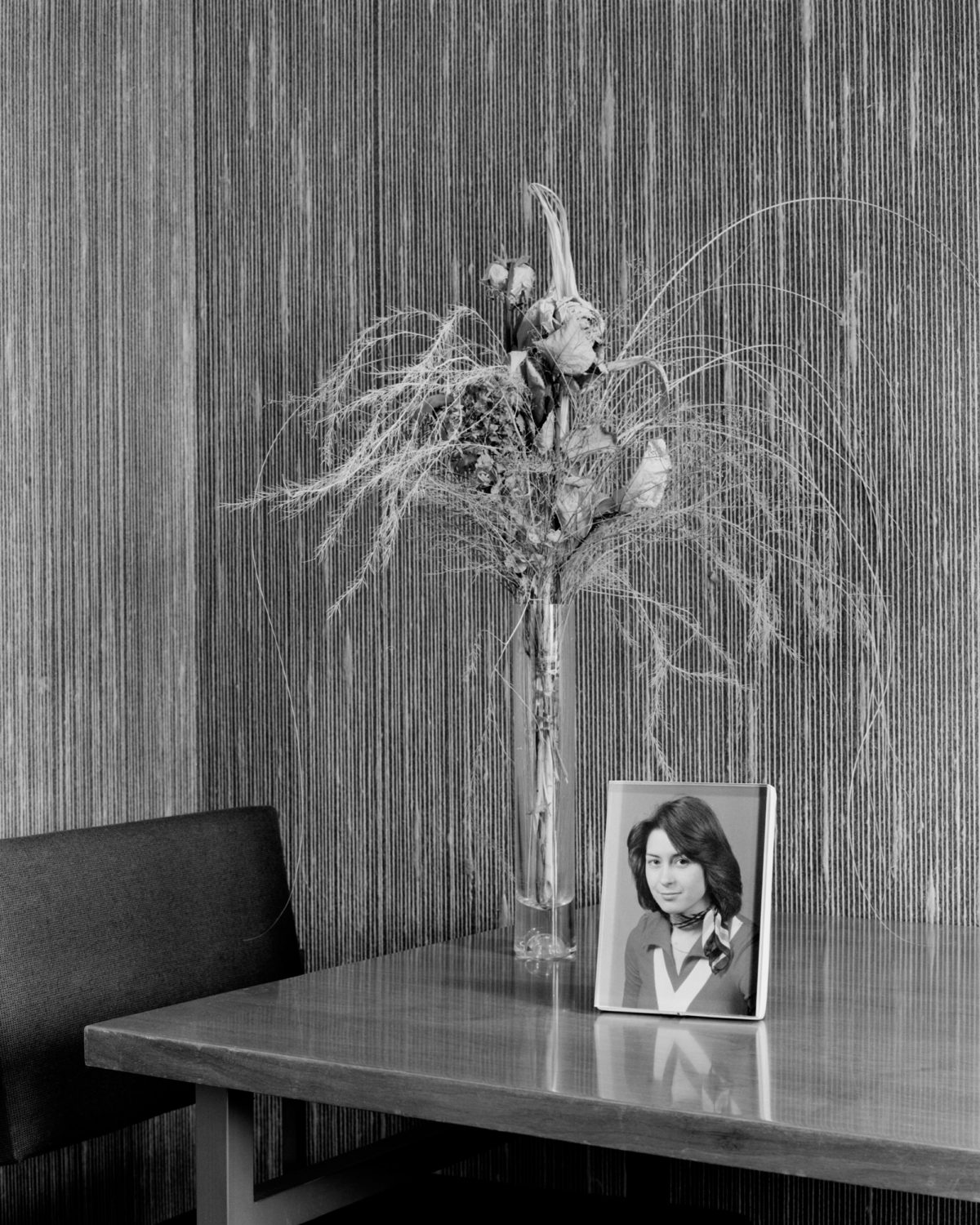

We’ve talked before about your restrained aesthetic tendency in this project – of its reluctance to disclose the subject at its centre, your mother, Ute. The sort of Black Sun around which the rest of the work orbits is a photograph of her body, in a sealed envelope, which you’ve never seen. Other images in the series – still lifes of family memorabilia, portraits of subjects turning away from the camera, shots of other media by its nature silent because different and therefore inaccessible (a cassette tape, a spool of 8mm film) – approach the subject obliquely, tangentially. Did you feel after the Zandvoort trip, which was an attempt to address the subject head-on, that by going after the facts, truth – or at least the version of the story you had come to know – couldn’t be told straight?

The photograph of her body is contained in an envelope alongside a copy of her death certificate, both issued by the Dutch authorities. I knew that opening that envelope was one step further than I wanted to go, so instead I decided to make a series of photograms: an object is placed on top of photographic paper and light is passed through, creating an indexical 1:1 image on the paper. The more light that was passed through the envelope, the more that was revealed, but somehow this process also withheld the image of my mother, while simultaneously revealing its physical existence/presence. Although a lot of other images came before these, the essence or conceptual framework of this piece is a good barometer in reading how the other works operate, and indeed how they come to form a constellation, to borrow your analogy, of meaning that support one another. There’s this inherent push and pull between what is being revealed, and what’s obscured – a symbiotic relationship that acknowledges the weight of the subject, but also crucially allows for tension to exist throughout the project, resisting the kind of personal specificity that I think would have killed off the work before it even began. That directness in filming the beach ten years ago, the place where she died, was foundational, but you’re right that it felt too straightforward or one-dimensional.

Yet this isn’t, strictly speaking, phototherapy – at least not in the way Jo Spence conceived of it, set in the broader framework of psychoanalysis, with co-counselling and the possibility of active change. Spence’s images are very raw – some, in fact, quite poor from a technical standpoint – while yours are beautiful, carefully crafted objects (the frames, which you made yourself, are an important part of the work). That said, you’ve mentioned that the project has allowed you to process the inconceivable fact of your mother’s death and to discharge some of that past pain, and so it has been in a sense therapeutic, healing, in the same way Spence’s reckoning with her cancer was. Can you talk about that?

I think it’s important, here, to mention that psychoanalysis has always acknowledged and drawn on the potential of the non-linguistic, and notably the unconscious motivations of the photographic image. There are clear parallels to make between the functions of the unconscious, as psychoanalysis understands it, the fragmentary nature of memory, and the optical abstractions created by the photographic apparatus. Although I’ve not explicitly invested in a psychoanalytic reading of my process per se, nor have I considered this phototherapy, some aspects of psychoanalysis are pertinent to the work and its evolution.

The question of whether there’s been any real healing involved is one I’ve been asked before and that I can’t answer with any certainty. My understanding of loss and grief, the function of memory both collective and personal, has expanded and matured. I’ve gained an ownership and confidence from the thing that I thought made me weak, but it’s a tightrope between processing previous negative emotions, acknowledging that, and moving past it to some future place where the centrality of this trauma is moved aside.

Beyond the work of crafting a kind of non-verbal language through images and objects, every other decision thereafter also felt important. The framing, as you mentioned, was conceived to reinforce motifs introduced in several of the photographs, and the installation in each exhibition considered the architectural space of the gallery, and how meaning could be extended through spatial composition and installation. One way I was thinking through these pictures was as temporary monuments (objects of memorialisation) created for the camera before being taken apart and returned to their domestic context.

Tell me about the practically ubiquitous wood.

The work was all created in the rural village in southern Germany where my mother grew up, and where my grandparents lived. Early in the project, I filmed my grandfather and me chopping wood together, which was one of the last activities we would undertake before he passed away. There was something in that activity and shared labour and the significance of wood that intrigued me.

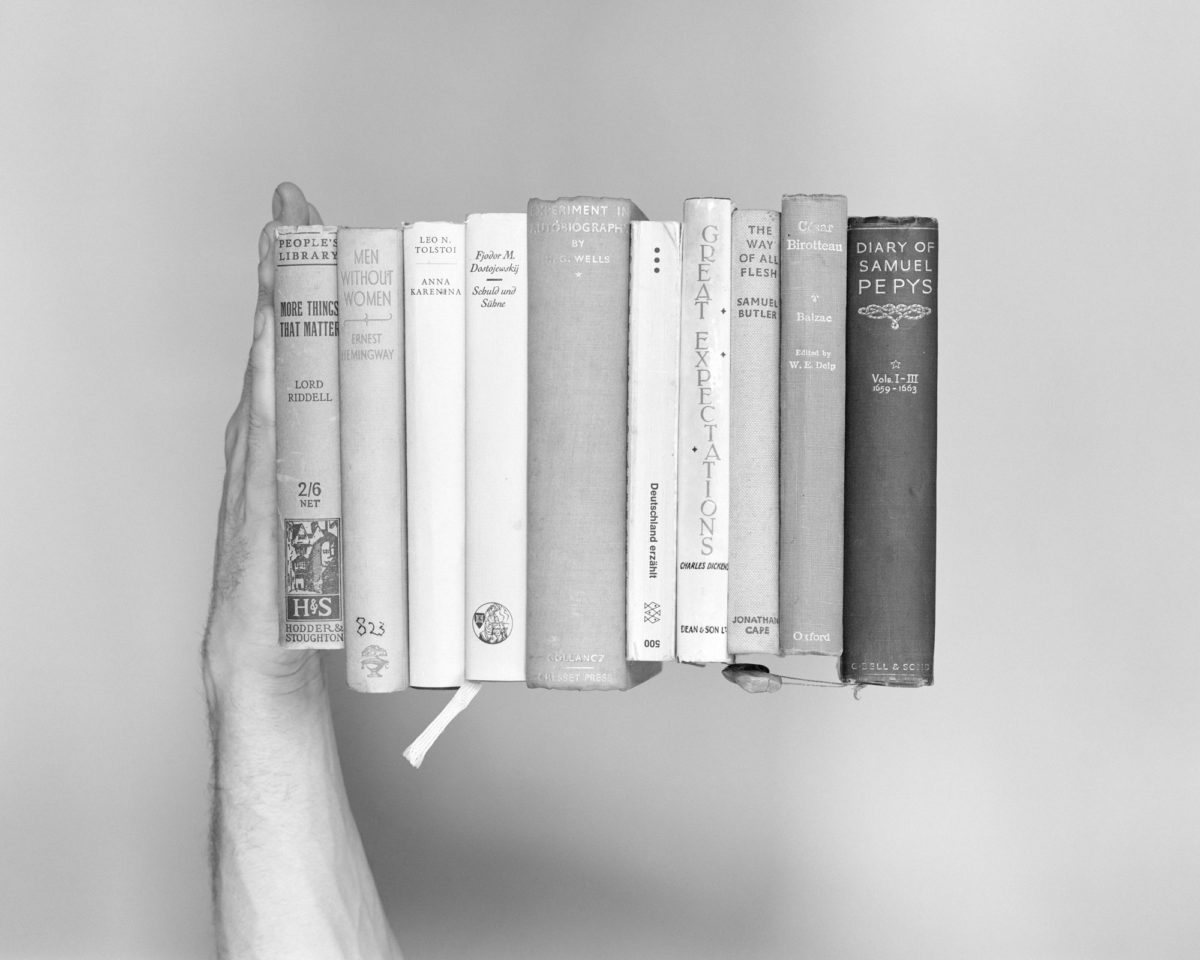

The beech tree, in German Buche (‘Buch’ translates directly as ‘book’), is common to the region, and appears several times in the work in various forms. Chopped wood for me speaks of a specific Germanness. Some associations: the chopping of wood, the ordering and stacking of wood, the cutting and splitting of time, of growth, life and death, rebirth. In the exhibition, one of the logs I chopped with my grandfather is presented three times, as a concrete cast. A desaturated grey object, an indexical imprint of the original that presents the object but at the same time is an abstraction of the original – a gesture like that of the black-and-white photographs.

Is there an issue with the way our culture mourns and memorialises its dead? I’m thinking of the word ‘unforget’ – somewhere between remembrance and oblivion. How we preserve the memory of those we love while still giving ourselves enough space to get on with our lives seems to me a question you’ve been considering for a long time, and I wondered if you’d drawn any conclusions.

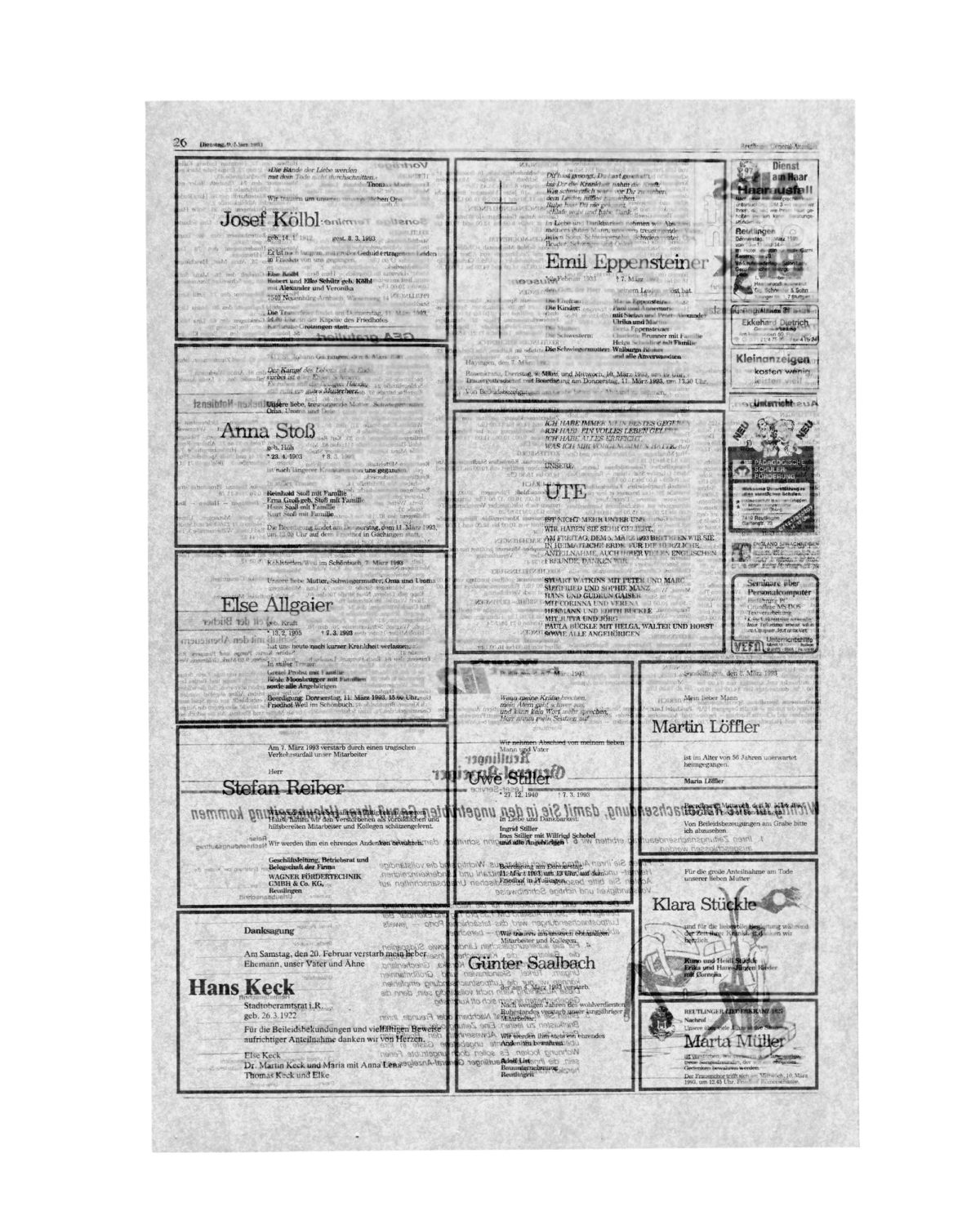

One problem, as I see it, comes from how we as an increasingly secular society deal with the notion of loss, and how our attitudes to grief have shifted. There’s a certain sanitised attitude towards the immediate aftermath of death that I think can contribute in some ways towards reinforcing trauma. From a young age I’ve found myself confronted with fundamental existential questions, and part of what drove the project was to understand myself better in relation to all this. I think I suffered a lot of latent guilt in childhood in relation to the loss of my mother that I’ve only now started to come to terms with since having a child of my own. The loss of those around us is an inevitability, but the specificity of the personal circumstances by which we are confronted is infinite in scope.

The Unforgetting started as a film, toured as an exhibition for several years, and is now a book. How did this most recent, most linear, iteration of the project come about, and how does it serve the work differently?

The book brings together more material than I allowed in exhibition form, and in that way it’s looser. But you’re right that it’s quite linear in nature, and I wanted it to be straight – no bells and whistles, just a confidence in the works as they were, unadorned, with a lot of space between the pictures. There are more straight photographs that were also photographed in the village where my mother grew up, which I think subtly grounds the work collectively, and reinforces the motifs. But these images also create ebb and flow in the work, allowing, I hope, for a poetic exchange and rhythm to take place.

The book is also accompanied by a separate, loose booklet, which contains a conversation between me and the writer Pauline Rowe and a series of installation images from the exhibition. This felt necessary in the sense that the work has, as you say, had a very physical existence in exhibition form, and is made up of objects, sculptures and photographs. In a way, it’s had another life before being a book, so I wanted that to be present in the book itself, but to act as an additional element, not an integrated part as it might if this were to be considered a catalogue.

You’ve now started your own family. You recently moved out of your London studio after almost a decade and a half and relocated to Prague. In the brief essay at the back of your book you say it feels important, at this point, to move on. Why – and what, I suppose –now?

That final line in the essay is really about realising how important it is to be present, and to not live your life through regret or sorrow for the past. But I think it also related to the passing of my grandmother, in that it feels like I’ve managed to achieve in some way what I set out to do; her passing and the very real emptying of her home where all of these photographs were made has made me realise that this is the end of something, a life marker, and hopefully the beginning of something new. As you say, I’ve recently moved over to Prague, and hope that this will bring with it some fresh perspectives, renewed enthusiasm, and that I’ll find something else I want to say with my work.

Learn more about Peter Watkins

Oliver Shamlou is a writer and editor based in London.

Read more Photography+ here