From issue: #19 Image Flow

Why are bricks-and-mortar galleries creating internet projects, and what are they doing with photography? Photography+ editor Diane Smyth finds out more from curators at Fotomuseum Winterthur, The Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru, and Somerset House, London

Based in a small city in northern Switzerland, Fotomuseum Winterthur is a leading photography institution. In 2015 it employed its first digital curator – Marco De Mutiis, a researcher with links to Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts and London South Bank University’s Centre for the Study of the Networked Image. From 2015–22, De Mutiis led the project team of SITUATIONS, and he is now spearheading Permanent Beta, a new initiative that will form a large part of the institution’s public face as it closes for renovation in 2023–25. De Mutiis explains.

‘In our experience, online is a great space to show process, which doesn’t always

work so well in the exhibition space. Permanent Beta is an infrastructure for

the museum’s staff to come together and show their research into digital

network images. It’s connected to the exhibition space but instead of having

the physical and online space simultaneously occurring [as with SITUATIONS, Fotomuseum Winterthur’s previous online research lab], we have temporarily separated them. Permanent Beta is an online platform to visualise our research, and that research will culminate in 2025 with a major group exhibition and publication at Fotomuseum Winterthur and hopefully beyond.

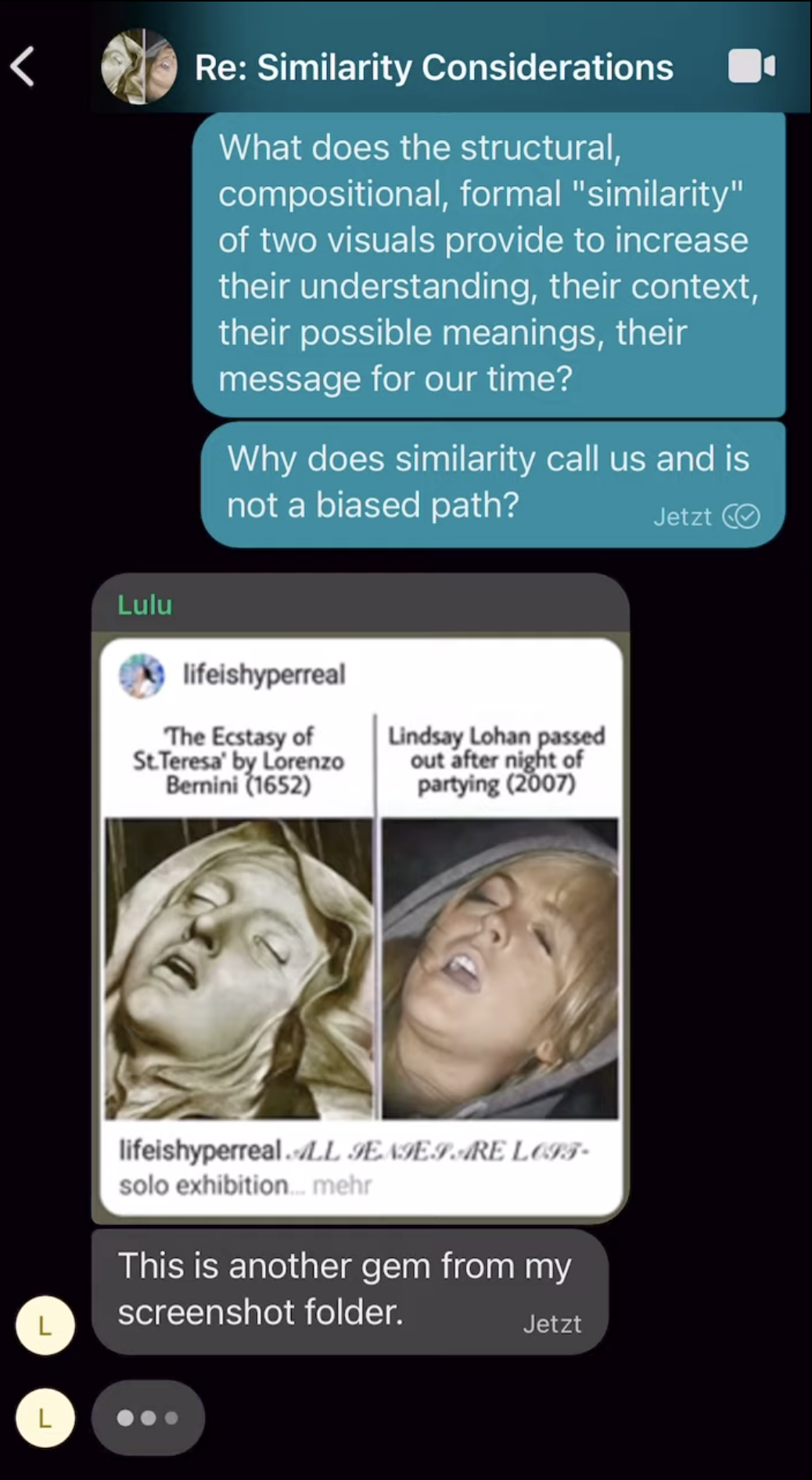

‘We will spend two years researching our topic – this will allow us to dig deeper than in SITUATIONS, in which we worked on three to five exhibitions per year. The first topic we have chosen is ‘the lure of the image’, which is dealing with the seductiveness of the image, how images entice us, how they even cheat us in different ways, from clickbait to the attention economy of YouTubers.

‘On Permanent Beta, we have a section called ‘Marginalia’, in which the staff share their research and ideas, our notes and unfinished thoughts. We also have a set of audio broadcasts, which are available on every podcast distribution platform. In these broadcasts we’re asking experts from the world of photography, ‘When was the last time you felt cheated by an image?’ They’re giving very personal stories – how they were fooled by a picture of an apartment on Airbnb or fake images from the Russian invasion of Ukraine – so it’s an introduction to the different ways in which we understand ethical issues.

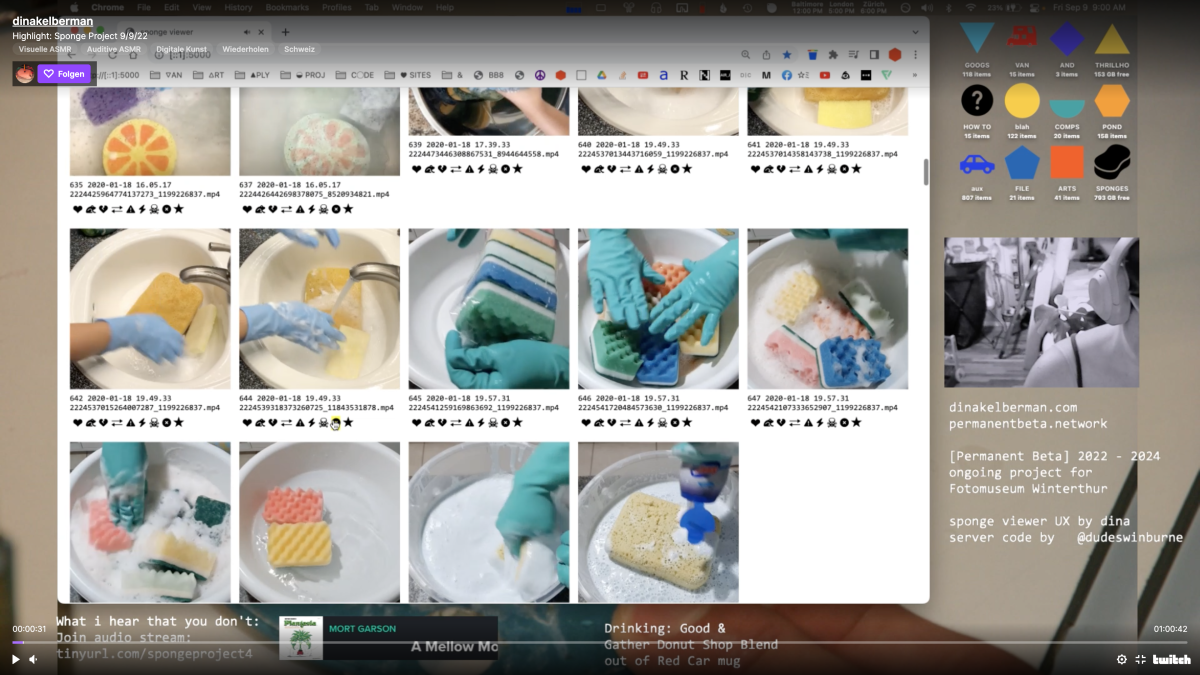

‘We also wanted to experiment with formats and being more accessible, so the American artist Dina Kelberman is working with us on a project on ASMR [autonomous sensory meridian response] videos in which people touch sponges. There’s a small but growing community of people who interact with sponges; it’s been wonderful to see. Another element is we have curatorial meetings that are open: every two weeks we have a meeting on Zoom that anyone can join online. It’s an experiment, but we really wanted to have a forum in which the museum can be more transparent.

‘In the 1990s, there was a utopia of cyberspace that was more democratic and less corporate, a culture of sharing in which knowledge was free and accessible to everyone. Since then, we’ve seen the emergence of web 2.0 and more and more locked content. The way I see the museum online is that we can offer all the knowledge we produce here in a way that is accessible and free. I think now more than ever it’s important to have institutions that can offer space for cultural reflection, and that can be critical.’

Museum of Art & Photography Bengaluru

Based in Bengaluru, India, the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) opened a purpose-built institution in February 2023, relaunching its website at the same time. MAP was founded by Abhishek Poddar in 2011, however, providing access to a collection of more than 60,000 works including an extensive photography archive. The museum has digitised its collection and collaborating on the online initiative Museums Without Borders with institutions such as the Rijksmuseum. Last year MAP Academy launched an online education programme, and an encyclopedia. Nathaniel Gaskell, curator, writer and director of the MAP Academy, explains.

‘The word “photography” is in the name because photography is such a significant part of the collection. Abhishek was a pioneer in collecting photography – he was one of the earliest to do so seriously in India – so the archive is characteristically diverse as well as vast. We also wanted to make it obvious that photography is included, because the perception persists amongst the public that a museum might not contain photography. MAP also makes for a good acronym.

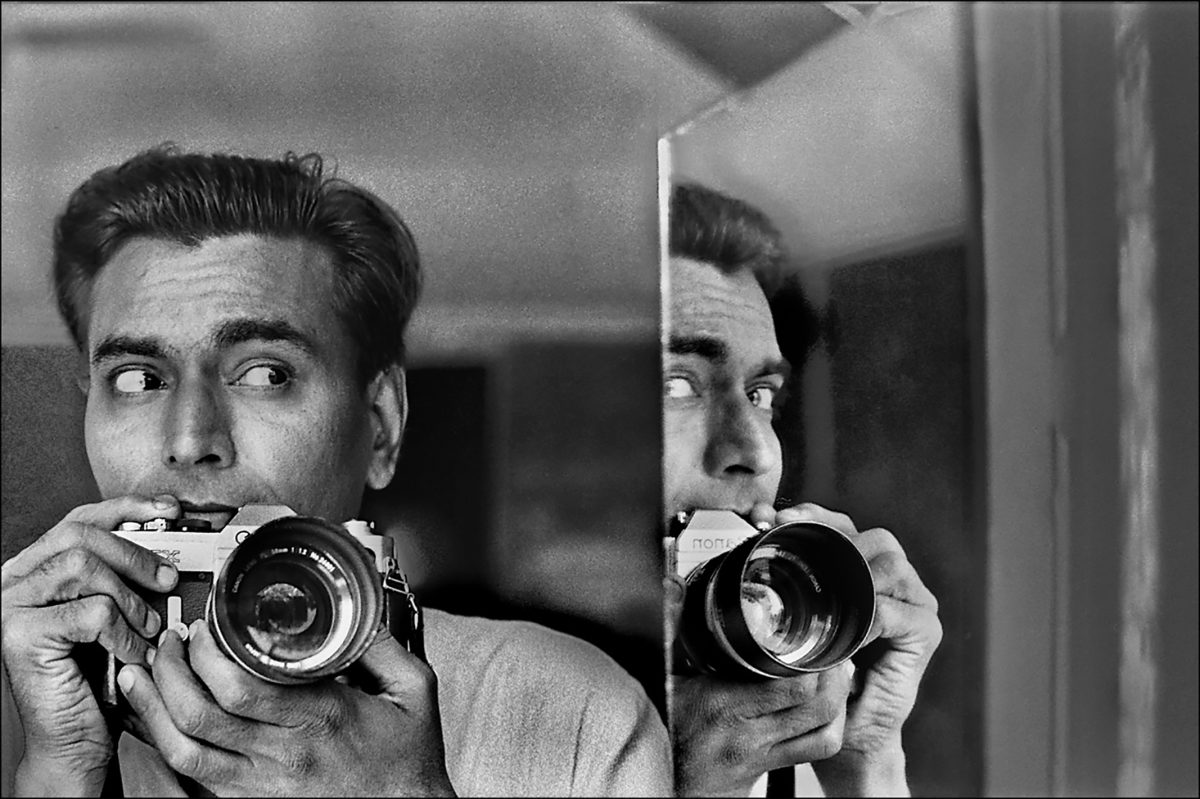

‘You can think of the bulk of the photography collection in two parts. The earlier part includes many typologies and views by early colonial photographers in India, but also work from local portrait studios from the early twentieth century. The second key part is work from the 1960s to the 2000s, including lots of documentary photography by various members of Magnum, such as Raghu Rai, as well as many other legends of Indian documentary photography. It also includes more conceptual work from India from the 1990s onwards, by artists such as Pushpamala N, Dayanita Singh and Annu Palakunnathu Matthew. We have a lot of popular culture too – early advertising, cinema posters, vernacular work.

‘We’re excited about the new museum and building our community locally, but digital will be another stream. Because of the scale of the country and the diversity of its audiences, working online allows others in India and beyond to see what we’re doing. Currently our online audience is about 80% based in India and 10% based in the USA – there is a lot of South Asian art in museums in America, and a huge Indian diaspora. The other 10% is from the rest of the world.

‘Bangaluru is an interesting place to be: tech has transformed it into a megacity in just twenty or thirty years. That means we can do a lot with digital. I think of the exhibitions, both photography related and otherwise, having a digital life, where rather than just putting the catalogue online, we can create something more curated and experiential. We can shape stories. We can drop in music, or background images, or material such as newspapers or contact sheets, to show something of the context in which artworks and objects first appeared. You can even use virtual reality, or augmented reality, to take works ‘off the plinth’.

‘The pandemic encouraged us to be more digital – using tech was always part of the plan, but perhaps not so intensely. We set up Museums Without Borders then. It’s a good way for us to build relationships with other museums and reach their audiences. But it also offers another way to talk about the work, because there are so many links between South Asia and the rest of the world owing to trade, colonialism and India’s incredible soft power and culture. I’d even say it’s often redundant to talk about “Indian photography”, as if it occurred in a vacuum, when in reality its evolution and influence are so interlinked with the rest of the world.

‘At the MAP Academy, I’m working with twenty-three young Indian art writers and researchers to create the online encyclopedia, which is a big project of MAP. These writers and researchers are based all over India, except for two who are in the USA doing PhDs. Of course, you don’t have to be from a country to write about its art, but I think a lot of strength comes from this approach, as in the past so much scholarship has been produced from Western institutions. Our researchers offer a certain kind of critical thinking, a decolonisation of existing narratives. It’s part of a much wider re-evaluation that’s currently happening, and that’s very exciting.’

An eighteenth-century complex in central London, Somerset House has fostered tenants from arts and culture since 2013, and encompasses Somerset House Studios, an experimental workspace designed to support artists for set periods. The venues host exhibitions and events, such as the annual Photo London fair, and Black Venus, a forthcoming exhibition by Black women and non-binary artists and photographers. In September 2022, Somerset House launched Channel, a curated online space drawn from the institution’s residents. Eleanor Scott, head of digital at Somerset House, explains.

‘Channel is Somerset House’s new curated online space for art, ideas and the artistic process. As well as presenting newly commissioned cross-disciplinary works, it explores and unpacks the artistic process and thinking. Somerset House is home to over 200 artists and creatives, including Somerset House Studios, and Channel draws on this unique community to drive a distinctive and evolving programme of original films, podcasts, talks and curated content.

‘A selection of artists and work that feature in the wider cultural programme at Somerset House is presented on Channel, in the form of editorial content such as filmed conversations, documentary films and artist-led podcasts. Black Venus will be covered on Channel, for example, though the output is still in production and to be confirmed. But as the home of cultural innovators, Somerset House also connects creativity and the artist with wider society, producing unexpected outcomes and unexplored futures, intensifying creativity and multiplying opportunity to drive artistic and social innovation.

‘We’re used to experiencing the work of an artist in its final form – in the gallery, on the stage, or mixed on an album – but the process of making a work is often where experiments happen and exciting ideas are formed. Much of the work we present on Channel is conceived and made in the building, from start to finish. A lot of the content on Channel goes behind the scenes on that process with the artists themselves.

‘Somerset House Studios offers space and support to artists pushing bold ideas, engaging with urgent issues and pioneering new technologies. Digital content gives audiences an insight into the community and the work being made here. Working online means that Channel can explore how artists are working with digital technologies such as artificial intelligence and virtual reality, and can work with artists to investigate themes around technology, ethics, identity, care and many more. Working online also means Channel can engage artists internationally and build the audience of our cultural programme at Somerset House. The potential reach includes both UK and international audiences.

‘The name “Channel” reflects the idea of a TV channel, a separate channel which is filtered and a curated stream of ideas and perspectives presented through the artist’s lens. Somerset House pursues a spirit of “Step inside, think outside” for everyone, regardless of age, stage or background. It is a place to escape your comfort zone in the safest way. It freshens minds, eyes and the world at large.’