Around the time of Co-optic, at the beginning of the 1970s, British photography was changing rapidly, as never before.

Especially in terms of institutions beginning to support the ‘new’ photography. The new photography itself, which emerged from the so-called colour supplements, Swinging London, renewed British prowess in photojournalism, and magazines such as Creative Camera and Album, kicked off a notion called ‘independent photography’, whereby photographers determined to make work for themselves rather than commercial clients – using the medium as a means of self-expression or political action rather than as a servant of media businesses.

The problem, however, with being ‘independent’ is that not only are you essentially swimming alone, but how do you make a living from photography? The notion of photography as a commercial gallery art had not yet surfaced in the early 70s. Then, as now, if commercial work was not for you, the other viable option was to teach photography, although the courses then were very different, and slanted towards the functional rather than the glamorous side of photography.

So independent photographers felt rather isolated, dependent upon their monthly fix of CC or Album. But help was at hand. In 1971, Sue Davies opened The Photographers’ Gallery in London, and others followed steadily. They were all non-commercial, because there was not yet a photographic art market. Importantly, there were groundbreaking exhibitions of the best international photographers in London – Henri Cartier-Bresson at the V & A (1969), Bill Brandt (1970) and Diane Arbus at the Hayward Gallery (1974), and (it should not be forgotten), a memorable Atget show at the ICA (1971).

Even more crucially, the Arts Council, under the guidance of Barry Lane, began to fund photography and provide money for individual photographers and fledgling organisations showing photography.

And what were the photographic philosophies being propagated? As the name ‘independent’ implies, they were as singular as each individual photographer, but two general traits can be discerned. Firstly, a certain anti-commercialism was implied, although some of those who loudly advised their fellow photographers not to work for the Sunday Times or ignorant art editors, would do so on the quiet.

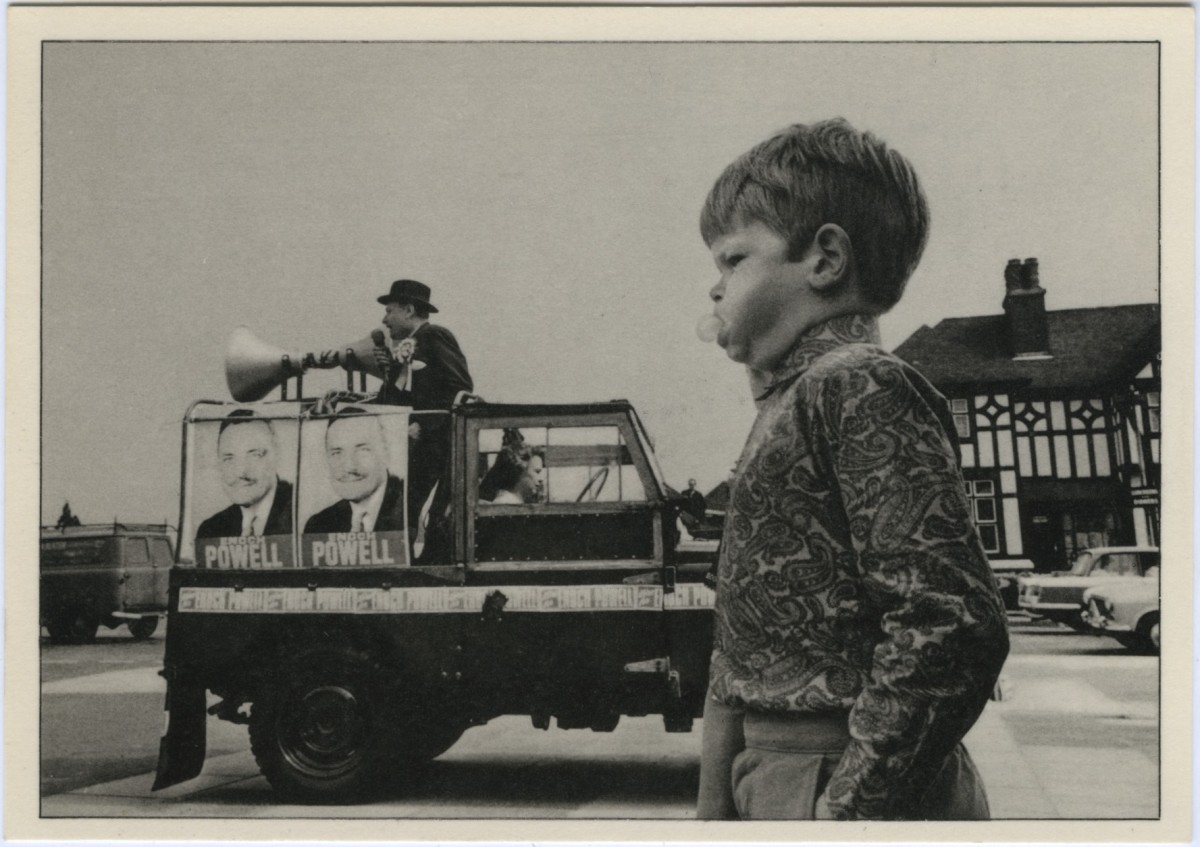

Secondly, a widely felt influence came, via Creative Camera, Album, and imported photobooks, from America, where British photographers looked with some envy at what appeared to be the generous institutional support for creative, independent photography. Tony Ray-Jones, a great influence upon British independent photography during his short career, had imported American attitudes when he returned to Britain in the late 60s, although if you wanted to drink straight from the source, as I certainly did, you could look towards such figures as Garry Winogrand or Lee Friedlander.

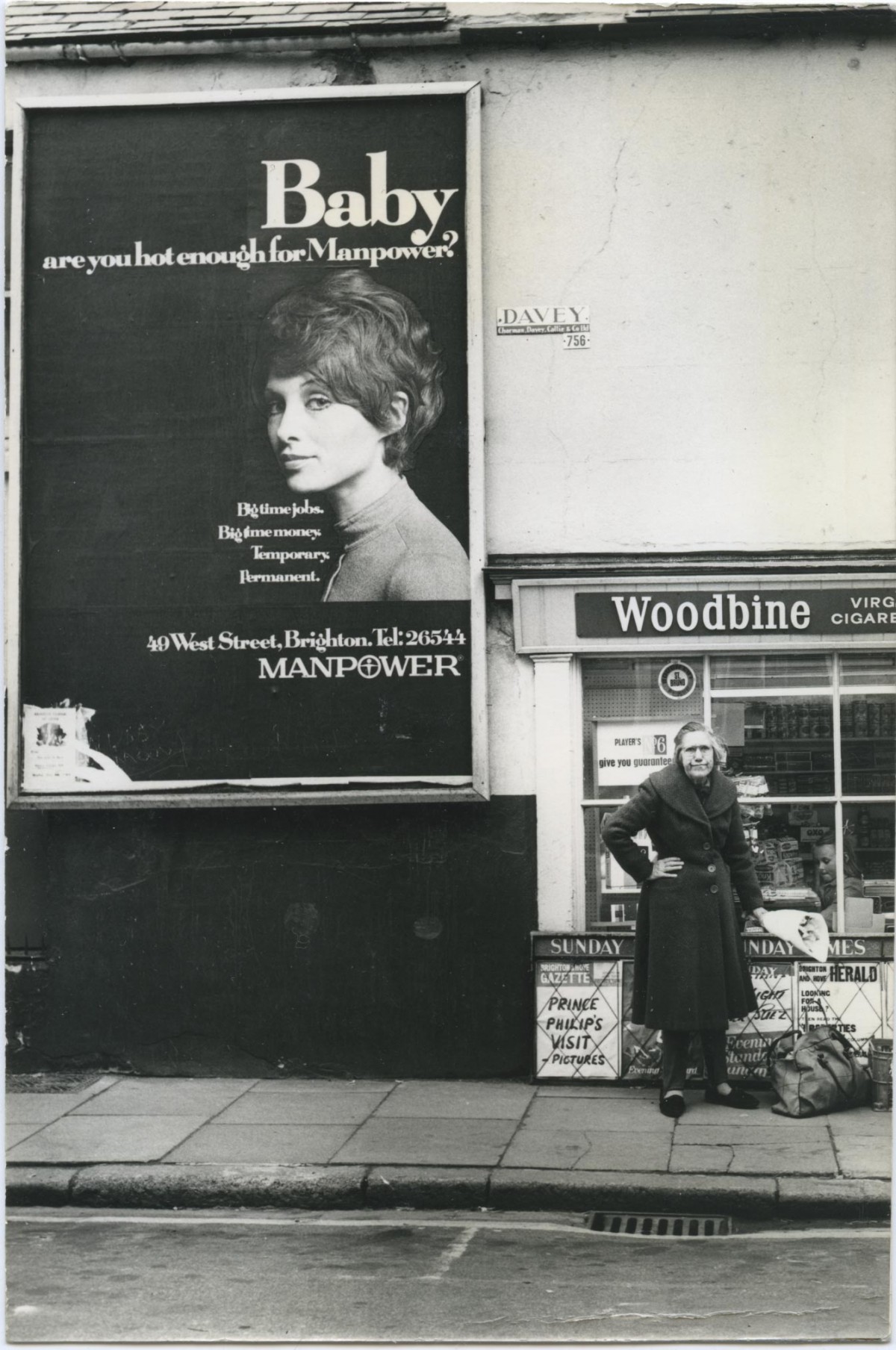

They were termed photographers of the ‘social landscape’, and although accused later in the 70s by more politically minded commentators of being simply formalists, it seems a deal more complex than that now. The ‘personal document’ was another term for it, and that was broadly the impulse behind the Co-optic photographers and the Real Britain postcards before the postmodern critique of modernist-formalism towards the end of the 70s almost threw the baby out with the bathwater. But photography was to continue inexorably towards becoming even more personal since those heady, innocent days.

And whatever we thought we were photographing, whether discovering the world or our own artistic psyches, from the perspective of the 21st century, we were photographing history. Of course, it was history as soon as we tripped the shutter, but it’s even more historical now. That is the true value of photography – not art, but the many varied, wonderful, valuable, infuriating, and sneaky ways the medium intersects with history.

–

Real Britain 1974: Co-Optic and Documentary Photography is on display until November 4 for Brighton Photo Biennial. For more information visit bpb.org.uk/2014