Lillian Wilkie, 02 May 2025

In the Spring of 1926, the popular left-wing German newspaper Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung (“Workers’ Illustrated News”) launched a competition, inviting workers who owned their own cameras to submit photographs showing the realities of their social and working lives. Despite its stated aims to be a paper for the workers, by the workers, the AIZ had up until that point relied on imagery supplied by bourgeois press agencies. Through the competition, the editors aimed to establish a pool of worker-photocorrespondents who could supply more lively and urgent photographic material.

The competition was to be profoundly influential. Within just a few months, groups of worker photographers had sprung up in Hamburg, Berlin, Dresden, Stuttgart, Chemnitz and numerous other towns and cities across Germany. By the summer of 1926, a new monthly magazine, Der Arbeiter-Fotograf, had been launched, and the following year saw the first national conference of the Vereinigung der Arbeiter-Fotografen Deutschlands, or the Federation of German Worker-Photographers , the slogan for which was “The Camera as a Weapon for Class Struggle”. Although widely associated with the Communist Party, and influenced significantly by proletarian photographic practices already enshrined in the Soviet Union, not all Worker Photographers had party affiliation; most did not sign up with the intention of using their camera as a weapon, but simply to learn more about this rapidly democratising technology, and practice techniques. Nonetheless, through collectivising and sharing resources such as darkrooms and chemistry, finding encouragement not from the photographic industry but from a politicised organisation, and looking carefully at society through the eyes of their class, the establishment of the Federation served as a valuable consciousness-raising exercise. Hitherto politically indifferent workers began to question who had previously been responsible for the representation of the working class, and to whose benefit. Many had their first tastes of collective action, cultural cooperation and the beginnings of an international mass movement—a movement which grew in size and energy until the rise of Nazism in 1933 destroyed its momentum and persecuted its leaders.

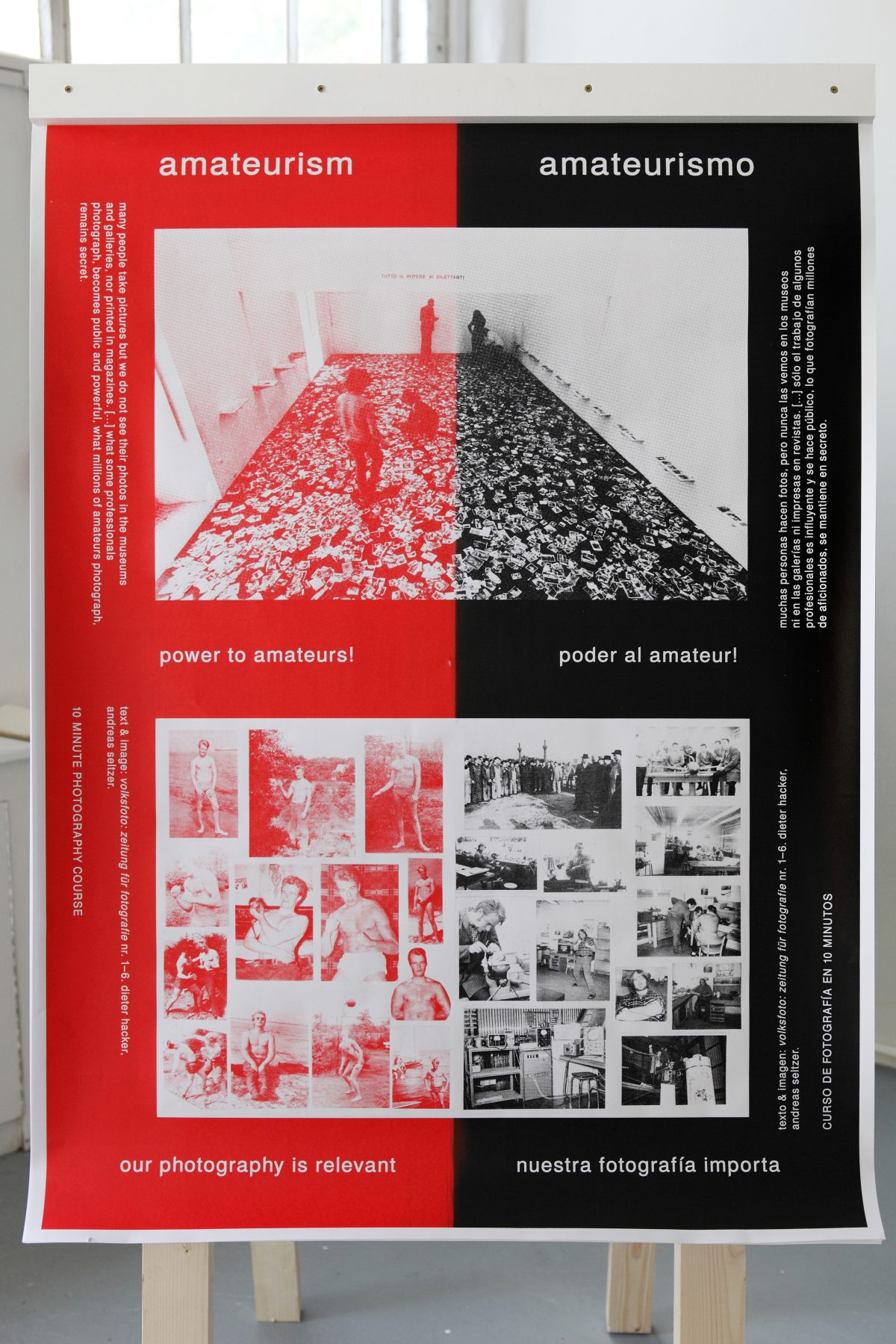

“Nobody ever told me about the Worker Photographers,” says Marc Roig Blesa of the Amsterdam-based Werker Collective, reflecting on his formal education in photography and moving image. “Socially conscious photography was always about August Sander, or Lewis Hine – it was all based on the idea of the author. The Worker Photographers were the first photographers I heard of who didn’t sign the work with their own names; they had this horizontality, they were questioning the media representation of the worker, they were making their own magazines. And I thought, ‘Finally, I found my family’”.

Werker Collective was founded in 2009 by Marc Roig Blesa and Rogier Delfos originally as Werker Magazine, a project engaged with the act of publishing as a means to intersect historical labour struggle with contemporary issues of class, housing precarity, gender, sexuality and ecology. The collective now works across expanded formats of print publishing and exhibition-making to question and problematise the relationships between contemporary social movements and artists, archives and methods of distribution. They maintain their own counter-institutional, open-access archive in Amsterdam, comprised of over 3000 historical and contemporary documents sourced in flea markets, second-hand bookstores and local museum and library collections, that resurface a hidden history of photography. The idea that environmental regulations and targets such as net zero are a threat to working class economic prosperity is a common neoliberal talking point, and Werker has made efforts in recent years to collect and archive material on ecofeminism and the intersections of labour and ecology, considering how to resist this right-wing narrative and explore the ways that non-human ecosystems can inform community practices of solidarity and care.

The influence of the German Worker Photographers is explicit, both in the prioritisation of “culture from below”, but also in the commitment to the blended authorship of a collective identity with a collaborative spirit. Significant inspiration is also drawn from the photography collectives active in the United Kingdom in the 1960s and 70s, including the Photography Workshop and North Paddington Community Darkroom, which brought photographic practices and techniques into existing spaces of community activism, and sought to establish working-class communities as the primary authors, subjects and audiences of their own visual material. Indeed, it was in Photography/Politics: One, the influential 1979 essay collection edited by Photography Workshop founders Jo Spence and Terry Dennett, that Roig Blesa and Delfos first encountered the Worker Photographers.

Whilst those twentieth-century photography collectives generally rejected the art gallery as a site of engagement, many—although certainly not all—of Werker Collective’s projects unfold within the framework of arts and cultural institutions. The role of the artist and intellectual in the formation of liberatory and countercultural movements is therefore a central concern, as is the status of the artist as a worker. “In our opinion,” write Roig Blesa and Delfos in their essay Yes With Us, Never About Us: Art/Workers, Solidarity and Privilege, “to exclude the artist from the possibility of also being a worker might have the effect of both mystifying the figure of the artist by assuming (traditional) concepts of authorship, and alienating their position in society, thus compromising the political agency of the arts at large.” It’s an approach which advocates for what Antonio Gramsci called the “organic intellectual”, who can articulate and visibilise the largely unseen experiences of the marginalised and oppressed, rather than maintaining a paternalistic critical distance. In other words, Werker is concerned with artistic practice that actually does politics, rather than rehashing and commodifying political symbols and gestures as part of a system of value production that mollifies the status quo. Whilst their projects are often hosted by galleries and museums, they work directly with a broad network of non-art world constituents including domestic workers unions, undocumented migrants, housing activists, feminist and LGBTQ+ action groups, and people with neurodiversities, all of whom are co-authors of the work.

This commitment to intersectionality especially finds its form in projects that synthesise work and desire, reimagining the working body as a queer body, and arguing for the alignment of body liberationist politics with housing and labour struggle. A Gestural History of the Young Worker (2019-ongoing) is a modular installation of screenprinted archival images and texts that critique the historically heroic representation of the body of the labourer, and the parallel oppression of queer and non-normative bodies. The installation is bathed in a soft red light, playfully proposing both the photographic darkroom and the sex club darkroom as factories for the production of desire. “Throughout history, workers and queers have been pitted against each other,” writes Werker. “Right-wing regimes and politicians worldwide appeal to workers as a beacon of stability and tradition while depicting queers as a threat to traditional values.” The work also addresses the tendency across certain sections of the international left to present workers’ interests as in conflict with the interests of queer and feminist movements, as they often do with the environmental movements considered bourgeois and indulgent. Amator Archives (2022) activates the Werker archive to propose new forms of knowledge around queer reproduction, exploring the politics of non-heteronormative families and assisted reproductive technologies, but also the ways in which queer identity reproduces itself non-biologically through cultural production, partying, activism and intergenerational solidarity.

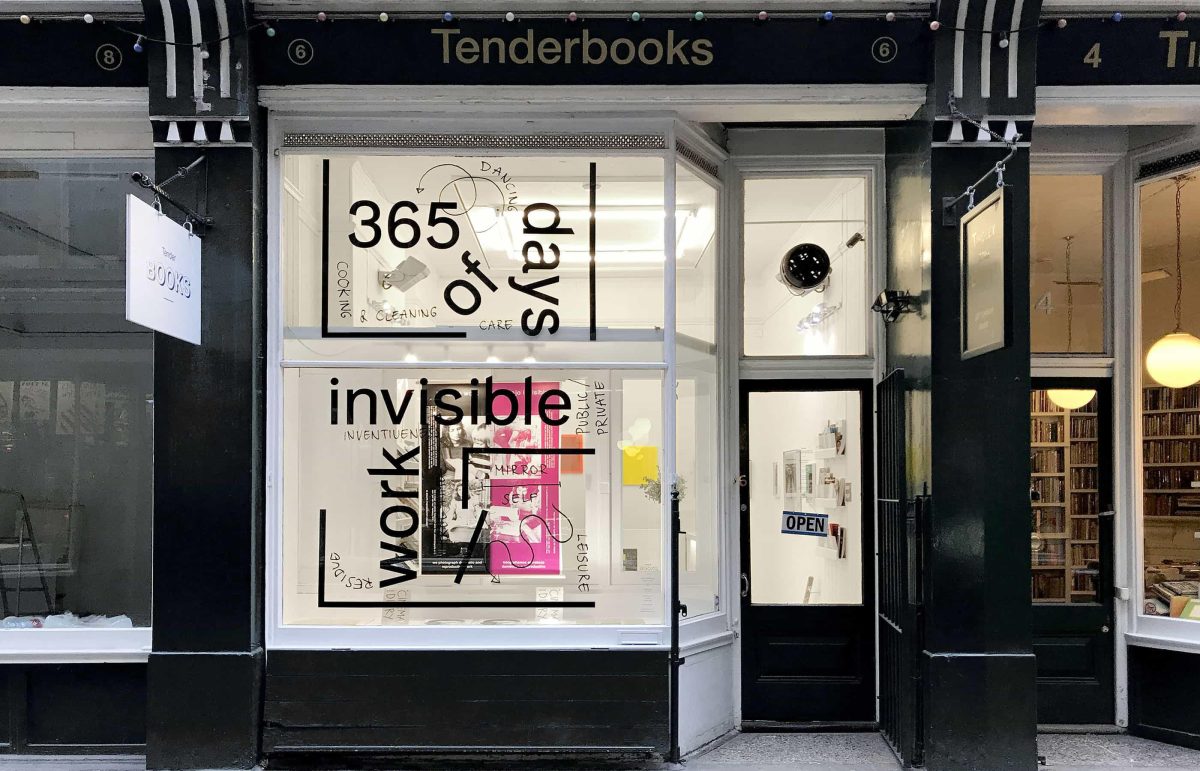

Other projects foreground photographic image-making as a tool for collective empowerment, building new and more emancipatory forms of representation. 365 Days of Invisible Work (2017), co-published as a book by Werker, Spector Books and Casco, assembles 365 photographs collected by the Domestic Worker Photographer Network, an online community of amateur photographers made up of migrant workers, gardeners, cleaners, mothers, carers and many others. It highlights the daily slog of domestic labour that goes unseen, underpaid and undervalued, and reflects on the contemporary conditions of precarious work. By creating their own photographic representations, like the Worker Photographers a century ago, members of the DWPN challenge the often callous depictions of these roles in the mainstream media, and raise awareness around living and working conditions, discriminatory policies and abusive employers.

Next year will mark the centenary of Der Arbeiter-Fotograf and the formation of the German Worker Photographer leagues. For Werker Collective, it’s an auspicious anniversary. In collaboration with Bristol’s IC Visual Lab, Werker plans to develop and publish Photography/Politics: Three, the unrealised third issue of Dennett and Spence’s seminal journal. Roig Blesa and Delfos met Dennett in London prior to his death, when he was in the process of distributing and rehoming his archive. Excited about their work and its intersectional and counter-institutional spirit, Dennett handed them a box of material related to the Photography/Politics series as well as his own research on the Worker Photographers, and marched them off to the local copy shop. Writing to them later, he encouraged them to publish a third issue, and symbolically bequeathed them the name, and his blessing. It remains to be seen how this new issue will develop, and what expanded formats and activations it might assume. What is known is that its focus will be on radical forms of education, and photographic practice as a tool for encouraging visual literacy in what is an increasingly alienating image-world. Werker Collective intends for Photography/Politics: Three to be a toolbox for teachers, educators and community workers to bring image critique and analysis into their practices, projects and curricula. It will also provide space to reflect upon Werker’s Community Darkroom series of workshops, which ran across a number of cities internationally between 2014 and 2018. Inspired by the North Paddington Community Darkroom founded in West London by Philip Wolmuth in 1976 (itself influenced by the Blackfriars Photography Project founded a few years earlier), Community Darkroom took the form of an itinerant school of radical documentary, with a library, mobile display unit and public programme. Community Darkroom encouraged participants to interrogate the power relations inherent in the act of taking pictures, sharing Wolmuth’s vision of a community photography project that not only democratised the means of production – cameras, darkrooms, and the printing press – but also politicised photography as a radical tool embedded in the lives and struggles of ordinary people.

Whilst deeply influenced by historical practices of photography, Werker Collective avoids any kind of nostalgic or rose-tinted naivety regarding the contemporary conditions of image production and consumption. Nowadays, after all, we view and produce images almost unconsciously. Ways of seeing, perceiving and communicating through photographs have undergone a profound transformation since the community photography of the 1970s. Growing up, I probably had my photograph taken once every couple of months on special occasions; my young daughter has her photograph taken multiple times a day. Media depictions of working bodies and workplaces have also shifted in character, as automation spreads, manufacturing declines and companies become increasingly image-conscious, restricting access to photographers. Even white-collar workers are dwindling in visibility, as remote work keeps administrators, technical support and sales workers at home. Against such a backdrop, Werker’s queer, ecofeminist and decolonial approaches feel increasingly vital. They encourage an unlearning of stale and patriarchal photographic histories that operate in deference to capitalism and colonialism, and instead incite us to dismantle notions of professional versus amateur, artist versus worker, analogue versus algorithm, and see ourselves anew.

Lillian Wilkie is a writer, editor and publisher based in London and East Sussex. She is the director of Chateau International, an independent imprint producing books, zines, editions and programming. She is co-director of Bound Art Book Fair at the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, and works in the book programme at Aperture. Her writing on photography, arts and publishing has appeared in a range of titles including Modern Matter, Dazed, Art Monthly, Elephant, and 1000 Words.

WERKER, founded in 2009 by Marc Roig Blesa and Rogier Delfos, blends labour, ecofeminism, and LGBTQ+ advocacy through diverse media, including publications, installations, and community projects, to critique visibility and silence in political contexts.