From issue: #9 Alternative Narratives

Conversations on Southeast Asian photography

Marissa Chen

Marissa Chen is our 2020-2021 Photography+ writer in residence

I first met Matca’s Ha Dao and director Jessica Lim on a muggy evening in December, 2017, as the lights were coming on in the rattling city centre of Siem Reap, Cambodia. Ha and I were both new photographers, having travelled from Hanoi and Singapore respectively, for the 13th edition of the festival, where Jessica – a former journalist and editor at Dhaka’s Drik Picture Library – then held the role of Asia coordinator.

The Angkor Photo Festival was co-founded in 2005 by VII Agency’s Gary Knight, French photojournalist Christophe Loviny and gallerist Jean Yves-Navel. Now in its 16th year, it is the longest-running international photography event in Southeast Asia. Together with Yangon Photo Festival (which Loviny also helped to found) and Shahidul Alam’s legendary Chobi Mela, the Angkor Photo Festival has cemented Asia’s reputation as a growing focal point in international photography, and has helped to pave the way for dynamic newcomers like Photo Kathmandu, Kyotographie, and Malaysia’s Obscura Festival.

That December evening, Ha and I found ourselves roommates at the Home Sweet Home hostel where, over the next 12 days, we would both work to produce an original series as part of the tuition-free Angkor Photo Workshop – a professional masterclass at the heart of the festival’s programming. Rigorously taught by some of the most established names in international photography, the workshop admits 30 photographers from across Asia annually, with graduates that include 2020 Magnum Photography and Social Justice fellow Uma Bista, photojournalist and Matca co-founder Linh Pham, and participant-turned-tutor Sohrab Hura.

In this exchange, conducted via email and instant messenger, I spoke to Ha about her photography practice and how it has developed alongside her role as programme coordinator at Matca. We go on to reflect with Jessica on our experiences at the Angkor Photo Workshop, the challenges faced by arts organisations in Southeast Asia amid a global health crisis, and the importance of making our voices heard from within – rather than beyond – the margins.

Marissa Chen (MC): 2020 has been an unprecedented year, to say the least. Although the Angkor Photo Festival team made the difficult decision to suspend the upcoming professional masterclass, you’ve introduced a Visual Storytelling Workshop exclusively for Cambodian photographers, taught by local mentors. There has also been a steady stream of activities like alumni-curated online exhibitions and Angkor Hangover meetups across Cambodia, where participants can watch screenings, attend portfolio reviews and even browse photobooks. Then, of course, there’s the public festival that will still be happening both offline and online from 26–29 November.

Jessica Lim (JL): The art of listening is having quite a resurgence as we reflect on our own isolation. Two of our guest curators for this year, Dennese Victoria and Swastik Pal, included a question in their open call which was simply ‘How are you?’, and they were bowled over by the responses. As the online space gets more crowded and Zoom-fatigue sets in, we also have to consider new ways of connecting with our audiences. A significant number of photographers will be rendered invisible due to the digital gap, since having lousy bandwidth or power-supply interruptions can make attending any online workshops or seminars an exercise in frustration.

The face-to-face nature of our events has always been key, in terms of both how we conduct our workshops and how we became a space for people to form genuine connections with each other. It’s a magical thing, to form lifelong friendships with like-minded peers on the basis of mutual respect and a desire to support each other’s artistic practice. It has helped us grow a close-knit, supportive photographic community in Asia. For the most part, I think the key actors in the region’s photography scene have been incredibly efficient at adapting to the new online space. The pandemic has hurt us, but it has also shown how fiercely supportive we are of each other.

Ha Dao (HD): Fun fact – I missed my graduation for the workshop.

MC: It doesn’t sound like you regret that decision.

HD: I majored in Communications at university. Most of my friends got jobs in ad agencies, and I was seriously considering that option. At the time, I only had one body of work – a project about me and my girlfriend that was created during a workshop with Jamie Maxtone Graham, an American cinematographer and photographer based in Hanoi. The first day at Angkor was nerve-wracking.

MC: All of us would gather at 9.30am to meet with our tutors, disperse to shoot, then come back to edit our work, often into the wee hours of the morning. You and I were often ships in the night – I remember you heading out to shoot just as I was getting ready for bed. We were documenting completely different areas, so our stories didn’t intersect, but I knew we both had the same acute understanding of what it was like to be making work at the time – the exhilaration and exhaustion of being in a foreign country, raking an idea over and over with a fine-toothed comb, not knowing whether the images would come. Photography can be a deeply isolating experience, but it was comforting to turn a corner after a particularly tough day of shooting and see somebody else from the workshop pointing a flash at a tree.

HD: Making Forget Me Not for the workshop was quite a foundational experience for me. I remember a particular session with Tania Bohórquez, who – along with Antoine D’Agata and Sohrab Hura – was my mentor for the class. It was like therapy. She asked psychological questions that made me realise what I was interested in exploring: intimacy, physical pain, the sometimes destructive nature of love and dependence.

At first, I presented myself as a customer in a Siem Reap beauty salon and asked to take portraits of the people who worked there. After shooting and editing during the workshop daily, it became clearer, like driving in the dark, that this would be a story about the women in the tourist-driven service industry. It was important that I hung around and participated – I spent quite some time in a low-key bar owned by a Vietnam-born Cambodian, got invited to a private birthday party and even performed on a stage at some point.

MC: Subsequently, you decided to incorporate self-portraits, even receiving makeovers from the beauty salons you visited, in an attempt to construct hyper-feminine versions of yourself.

HD: The experience taught me what I didn’t want: to take a photograph and go. Up until that point, I was trying to get as close as possible to my ‘subjects’. It soon became evident that the minds of others are quite impossible to penetrate and that I could no longer pretend to understand them. I remember being overwhelmed with sadness after making Forget Me Not – from both the stories told by the women who made a living on the street and the realisation that I was perhaps taking something that wasn’t mine to serve some obscure purpose. For that reason, I consider this series a point of departure.

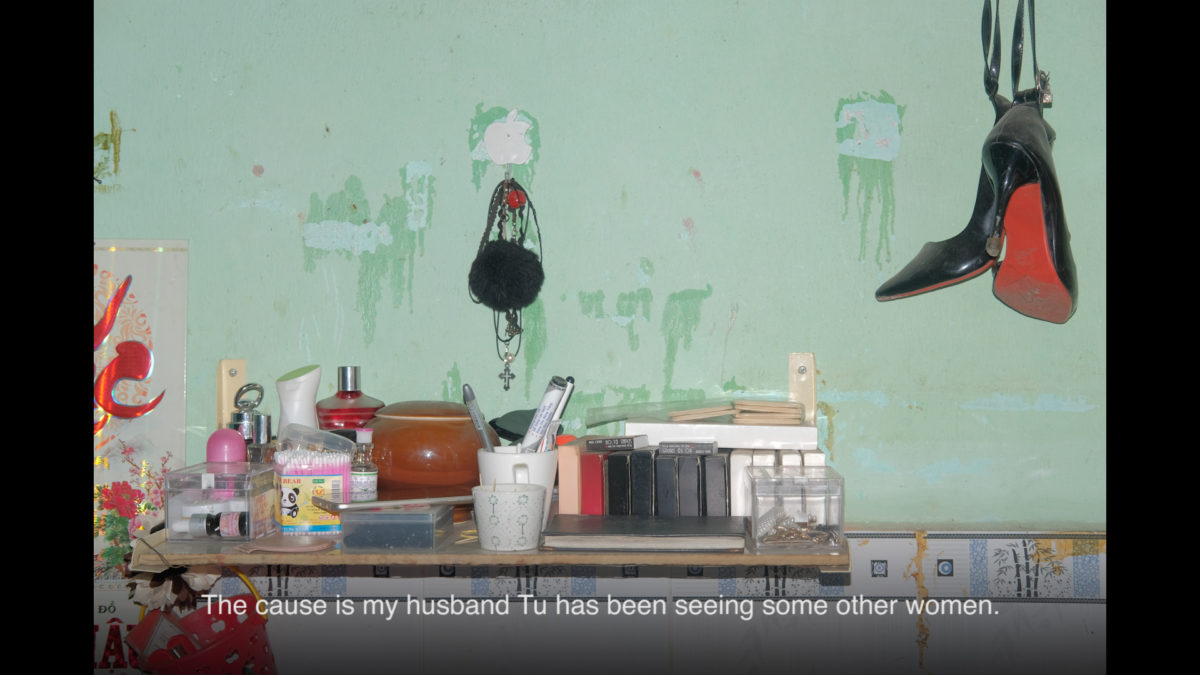

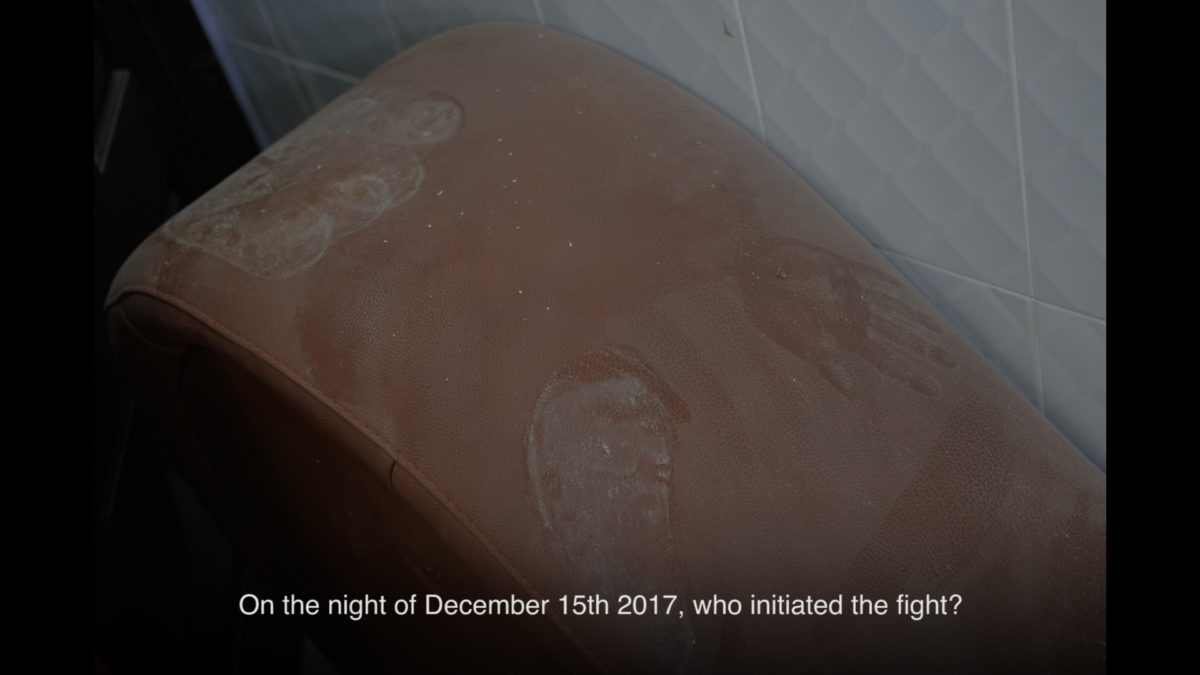

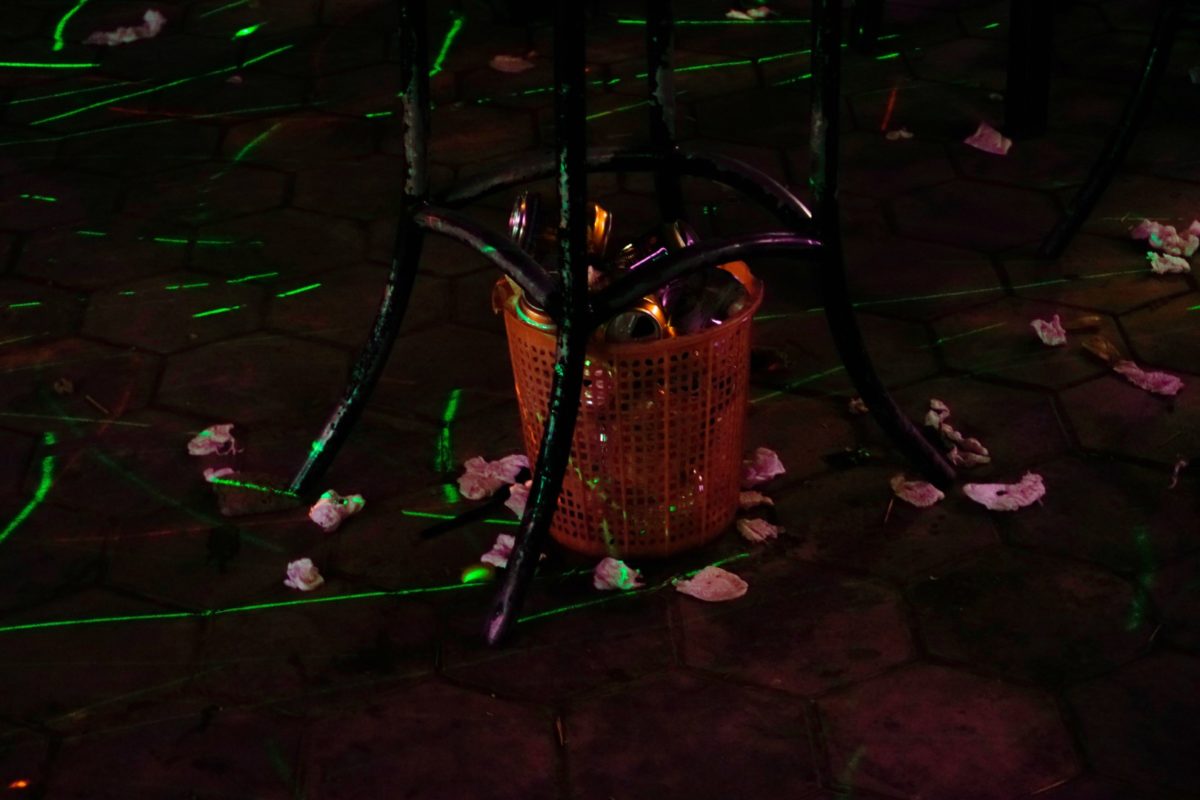

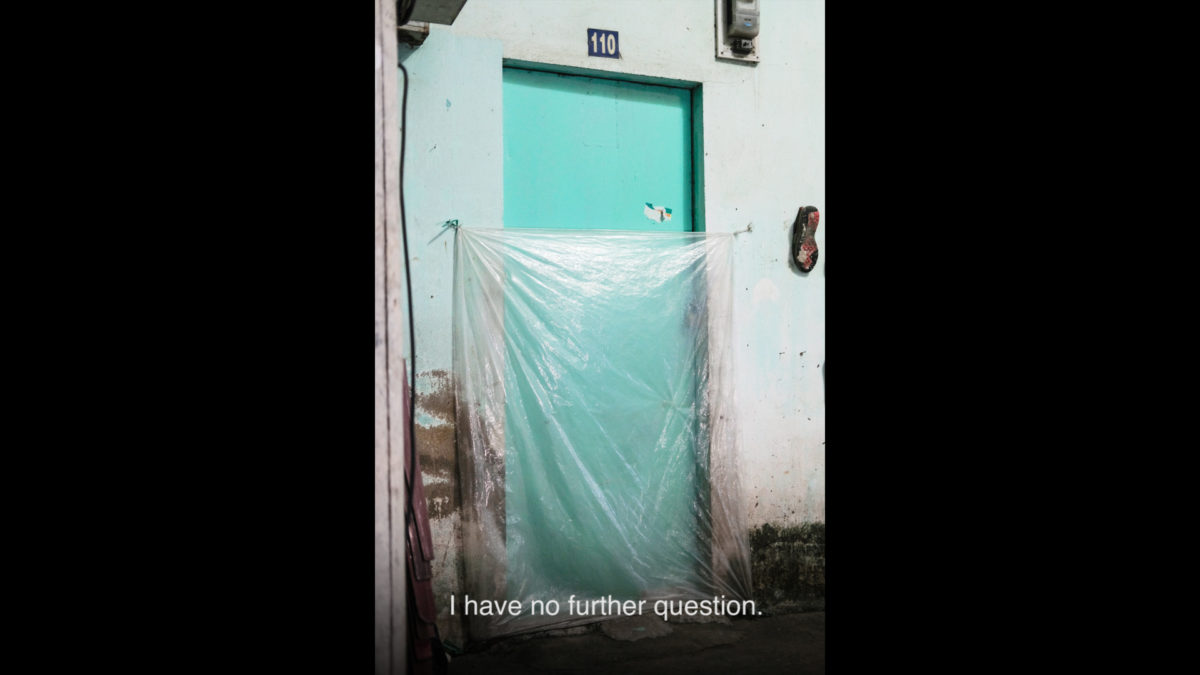

MC: This idea of participation takes on new meaning in your latest video project, All Things Considered, which you made as part of the Month of Art Practice, a residency organised by Heritage Space in Hanoi. The work is based on the 2017 murder of Tran Thanh Tu, who was decapitated and butchered by his wife, Hoang Thi Hong Diem. Some of the images are presented to us in quite a removed way. Others feel intensely immediate and intimate. We never quite know if we’re confronting the scenes as an investigator, the accused, or the victim. But you called the work an ‘interpretation’ of a true-crime story – why is that?

HD: This case made national headlines when it took place in 2018. Watching the three-hour-long trial on YouTube, I was amazed at how the judge panel and the accused could go over graphic and personal details, again and again, matter-of-factly. But even with the details fully laid out, I couldn’t say that I, or the people present in court, knew what really happened that night.

I took a one-week trip to Binh Duong – an industrial town right outside Ho Chi Minh City – where the crime happened. I divided my time among several key locations: the neighbourhood where the couple lived, where the body parts were found, shabby love hotels, a ‘film set’ for pre-wedding photography, etc. I gained access to factory workers’ residential areas – since that was the couple’s profession – and knocked on people’s doors to ask if I could photograph couples and their interiors.

Although I decided to stage and take photos out of context, observing and getting clues from specific environments still play a major part in my practice. Several learning points from Angkor stayed with me long after it ended – being present, taking risks, and always questioning one’s position.

MC: Let’s talk about your role with the independent art platform Matca, which began as an online journal and has since expanded into a dedicated art space for Vietnamese photography, as well as a publishing imprint, Makét. Growing up in former colonies in Southeast Asia, like the three of us have, we were accustomed to looking to publications or artists from the West for creative inspiration before turning to our own communities. But Matca (which means ‘fish-eye’ )makes it clear that to “turn a wide lens on an increasingly overlooked community of Vietnamese photographers [and] reveal the bigger picture”, it must put the needs of its local audience first, so as to not have language or culture be a barrier to entry like it so often is in the global photography industry.

HD: I first got involved with Matca in late 2016, while taking on odd photography-related jobs like lighting assistant, fixer, etc. As Matca grew, I went from being a writer and editor to a programme coordinator, and even an occasional event host. I’m curious about others’ practices and processes, and Matca allows me to reach out to photographers, both veteran and emerging. I just wanted to have the excuse to immerse myself in photography and learn along the way. Linh and I are greatly inspired by initiatives from neighbouring countries, like the Angkor Photo Festival, particularly their commitment to nurturing the local and regional community at large. Having a strong community at home is very important for me as both a photography practitioner and a facilitator – perhaps more so than being discovered, represented and recognised by major gatekeepers, which often happen to be North American and European platforms. I take pride in our original content, which is created by a diverse group of writers and photographers, all with different approaches to image-making. It has gradually opened up space for critical thinking about the medium, something that was deemed lacking in the scene at that time. There is no doubt in my mind about whom we want the conversations to reach the most.

MC: We have had many conversations about the problems of tokenism, and things like ‘diversity’ and ‘feminism’ have been reduced to sleek marketing tools with which to tell a ‘good’ brand from a ‘bad’ one. Certainly a far less talked about aspect of diversity in the global photo industry is the problem of economics and – in parts of Asia especially – political access. The Angkor team has worked hard to keep the workshop and portfolio reviews free to attend for all participants, but this is still a rarity. It’s difficult for photographers to join the broader conversation about representation – or even get a foot in the door – when they’re working out of places where journalists are routinely persecuted simply for doing their jobs, or where entry fees for international photography competitions are completely out of touch with local costs of living.

JL: It’s tough, that’s for sure. Even though we are a lot more affordable than other options, we are still out of reach for many. Photography in itself is already a profession (or calling) that is out of reach for many, considering that you’ll need to be able to afford a camera and, these days at least, a laptop. I have personally been interested in finding ways to commission or fund independent work in the region as the current ‘freelance’ culture makes it really difficult and expensive for original stories to be created.

HD: Local independent art spaces, including Matca, have learned to be self-reliant. With or without a pandemic, the question of sustainability often weighs heavily on us. It’s discouraging to see so many initiatives in Vietnam pop up and then disappear over the years due to lack of funding or strategic planning. Yet, it’s funny how we’ve still been able to produce work as usual, even during this globally disruptive time. Over the last four years, despite expanding to other platforms, the idea of a humble website that shares work and ideas about photography has remained central to everything we do, rather than a plan B to fall back on when programmes got cancelled. The very institutions that rejected our funding proposals for online activities before it became the norm are now starting to fund online programmes.

JL: When I first joined the Angkor Photo Festival team 10 years ago, it became apparent that our programme was a useful tool for North American and European platforms and publications to discover voices ‘alternative’ to theirs, as we typically featured a large amount of work from Asian photographers. Our programme director then, Françoise Callier, always advocated for new discoveries, and she had a knack for finding great work. It’s funny. The term (alternative) itself is not controversial, but in the context of this particular industry we are in, and its history of colonial narratives and economic exploitation, I am certainly sensitive to labels that highlight differences, even if it is for the sake of celebrating them. ‘Diversity’ and ‘inclusivity’ are great things to strive for, and I will always encourage this, but – truth be told – I am getting a little weary of all the pats on the back simply for seeing what has always been there. We all have our blind spots, we all need to work at recognising and addressing them.

HD: Certain issues relating to my identity as someone from a minority group are still of interest even though they might not directly define my practice. I have been trying to strike a balance between holding my own position as a queer woman photographer and not being pigeonholed by it. Currently, I’m just identifying as a cat owner.

Learn more about Marissa Chen Learn more about Matca here Read more Photography+ here