From issue: #9 Alternative Narratives

Big money is moving in

Julia Bunnemann

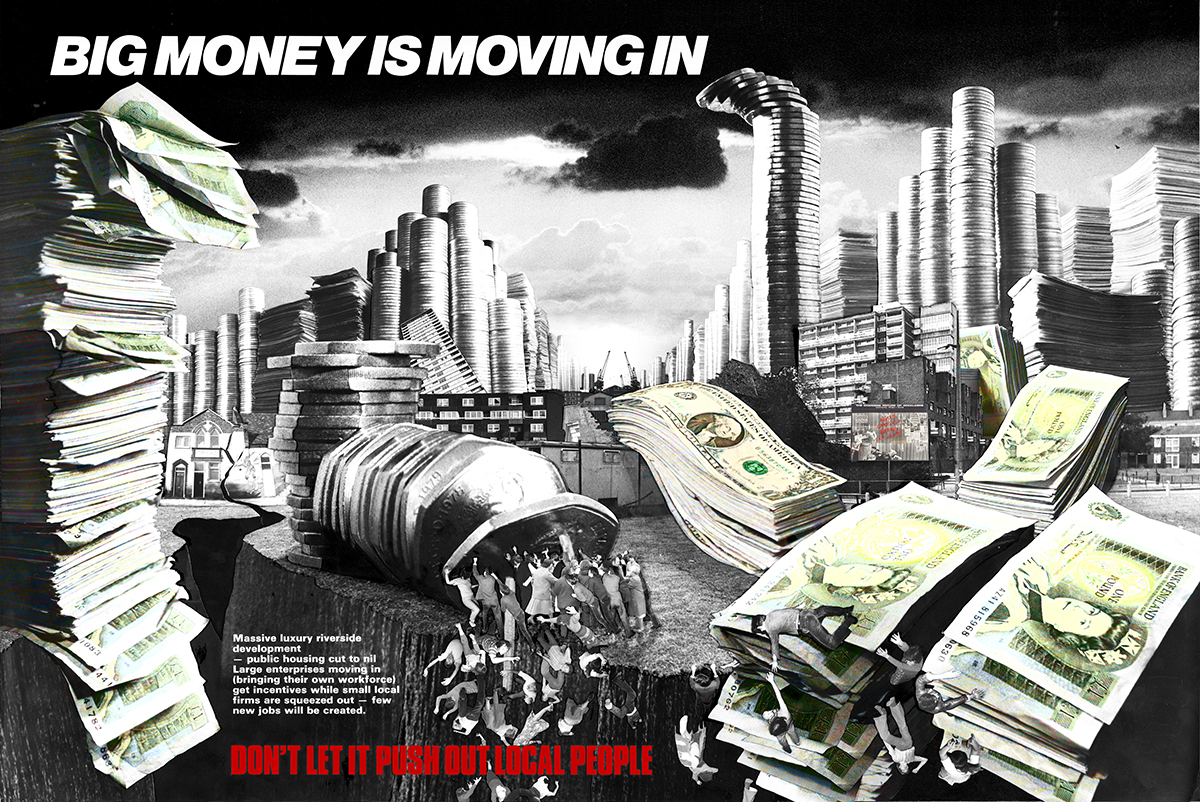

The words ‘BIG MONEY IS MOVING IN. DON’T LET IT PUSH OUT LOCAL PEOPLE’ alarmed locals when they appeared on massive billboards around the London docklands back in 1981.

Printed in giant capital letters, the text featured on 18 ft x 12 ft photomurals called The Changing Picture of Docklands, by Loraine Leeson (born 1951) and Peter Dunn (born 1946). For the work, the duo built billboards and appropriated a classic form of advertisement to create photomontages, redeploying the commercial aspects of the imagery in service of a collective good. This artistic form of urban resistance, and the associated campaign to oppose the rigorous efforts of the Thatcher government to ‘redevelop’ the docklands, remains an exemplar of alternative, collaborative approaches in contemporary photography.

In March of this year, the coronavirus lockdown forced people to avoid social gatherings and public places. As a result, the art world had to quickly find ways of operating and engaging beyond the traditional gallery space. Looking back to the flourishing anti-establishment attitudes of the 1970s and 1980s, when many artists were committed to finding new ways of distributing their work, was an especially fecund source of inspiration for different ways to explore photography. Leeson and Dunn’s photomural project particularly sparked my interest because it links to the theme of this issue, ‘alternative narratives’, on so many different levels. Just as empty public advertising space quickly became a favourable method of sharing art at the peak of the pandemic, Leeson and Dunn embraced a similar format as a way of making people aware of the massive impact that the hugely expensive redevelopment of the declining docklands would have on local communities.

© Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, all rights reserved, DACS 2020

Leeson and Dunn began working together as students. They made a name for themselves in the late 1970s by working on a successful campaign to stop the closure of hospitals in East London. For Leeson and Dunn, these campaigns were the beginning of more focused and strategic artistic and political activism and interdisciplinary work, including collaborations with unions and local politicians. After being approached by the local trades council, in 1981 they formed the Dockland Community Poster Project, which became a focused cultural campaigning group that linked various networks of resistance, their billboards representing just one part of the campaign.

Photomontages have a long history in art activism. They create an interplay of images, photography, language and culture, thereby producing a multiplicity of narratives, which often get lost in so-called straight photography. Furthermore, photomontage has traditionally been used to express political dissent, such as those made by the Dadaists – first to protest World War 1 and then to create socially engaging imagery in the late 1920s.

Leeson and Dunn’s photomontages evolved in consultation with local residents and the Docklands Community Poster Project steering group, and were carefully planned to ensure maximum impact. The large, visually arresting billboards, which clearly depicted how the proposed redevelopments would devastate the community, were built by the artists and carefully positioned near service and shopping areas to engage as many people as possible. Furthermore, they were placed in such a way to grab the attention of pedestrians – who were more likely to be locals – rather than people driving past. By engaging with viewers in this face-to-face manner, the intention was to make them collaborators in the resistance against redevelopment. The artists took their inspiration of the diversity of the revolutionary art in Russia and Chinese wall posters which had brought information to the people during the Cultural Revolution.

© Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, all rights reserved, DACS 2020

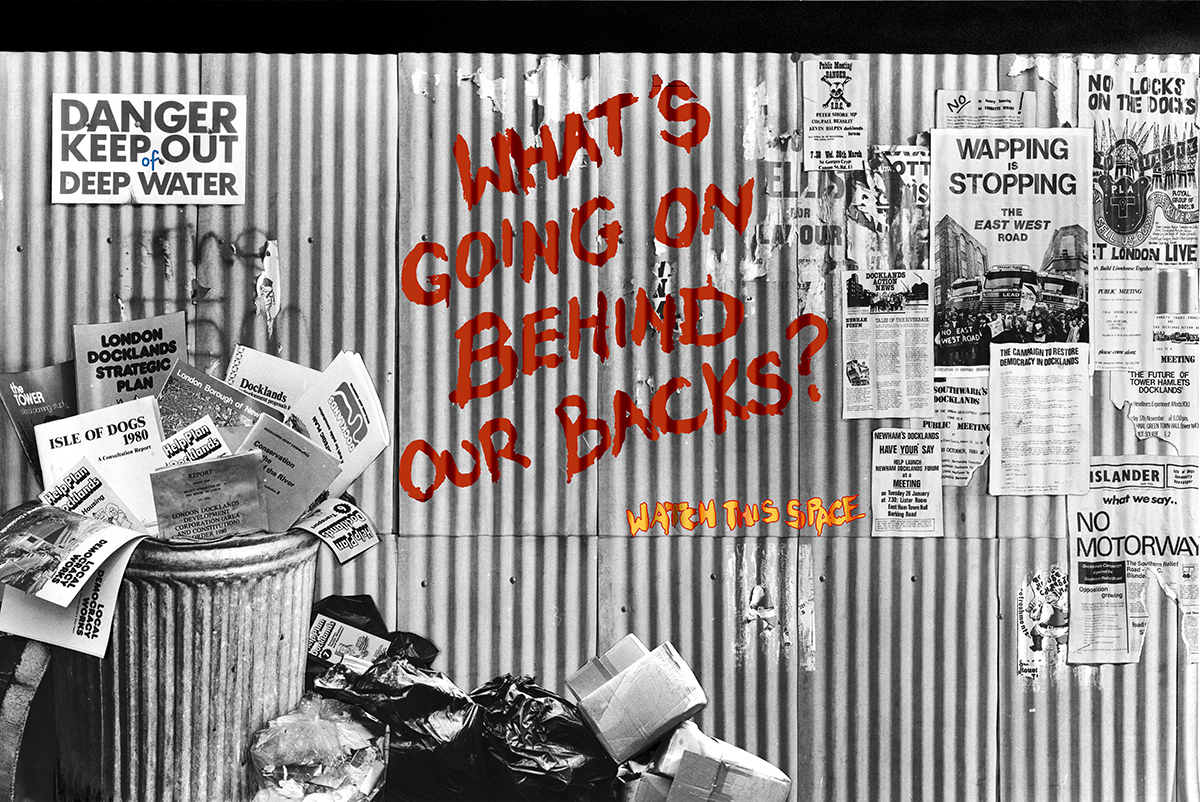

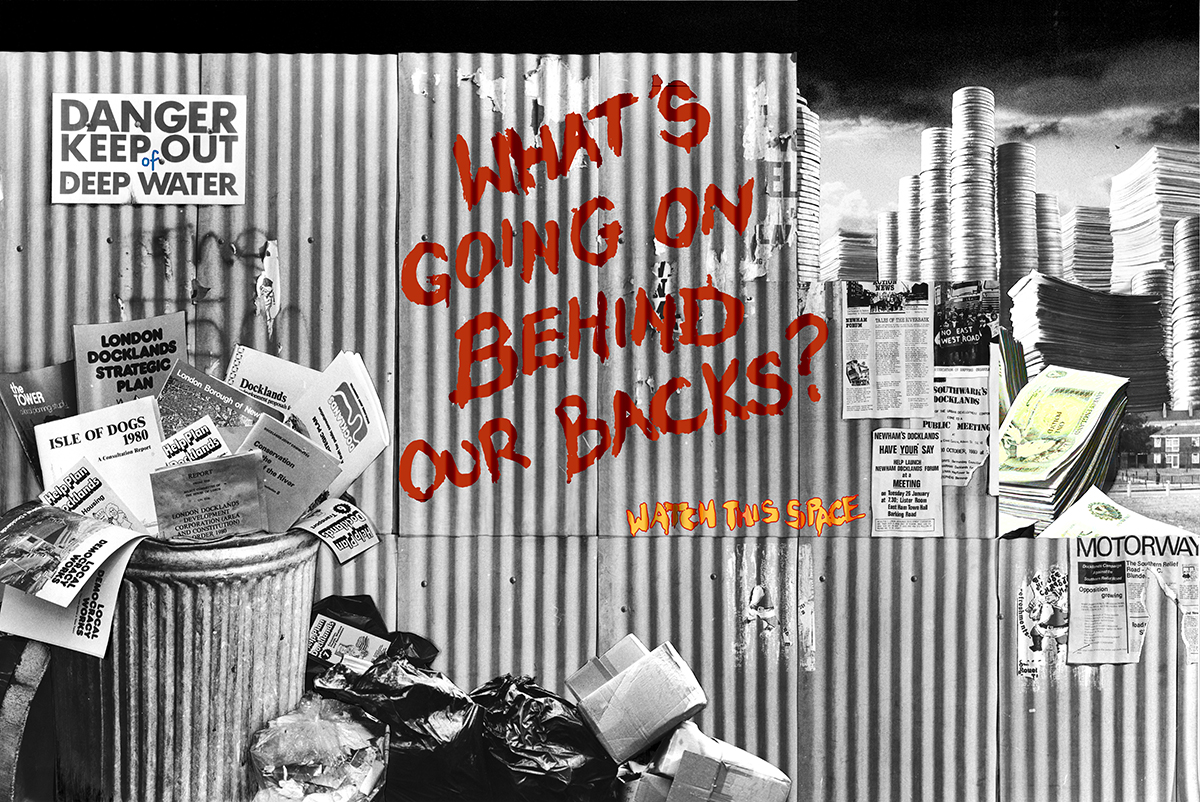

The Changing Picture of Docklands referred to image sequences representing a narrative and involved black and white photographic images selectively hand-coloured in translucent paint to highlight certain aspects. To enable this evolution, the photomurals were made as separate panels, which could be changed and replaced to steadily build a narrative. In a 1982 interview, Dunn revealed that this approach was also partly driven by financial constraints: by making and installing the murals in this way, they could be reused.

The first image was of a corrugated iron wall, which dissolved gradually to reveal mounds of shiny coins that reach towards the clouds like skyscrapers, towering over the local council blocks. Money comes to dominate more and more of the scene, as piles of banknotes aggressively cluster in the foreground, displacing people into an abyss. Most of these visual metaphors were based on comments made by locals at public meetings. ‘When people are angry or passionate about an issue, they tend to speak in charged metaphor,’ Dunn explained.

The scene becomes increasingly apocalyptic with every change to the billboard, until eventually it is shattered by a girl breaking through the oppressive hellscape – a source of hope, who invites the viewer to resist the developers’ agenda. The final image in the sequence is a montage of local activists and community groups in full colour, recalling both a clichéd Hollywood happy ending and the structure of a classic history painting. Unlike in classic advertisements, they created a pictorial world.

The combination of image and text is crucial to the dialectical power of photomontage and was used extensively by Leeson and Dunn. As the imagery in the photomurals changed, so too did the associated text. Each new phrase responded to and expanded on the previous one – almost like a dialogical exquisite corpse, progressing the narrative that the artists had constructed:

- ‘What’s going on behind our backs?’

- ‘Big money is moving in’

- ‘Don’t let it push out local people’

- ‘The scrap heap’

- ‘Is this the way to draw the community into planning?’

- ‘Shattering the developers’ illusions’

- ‘Our Future in Docklands’.

© Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, all rights reserved, DACS 2020

Leeson and Dunn’s photomurals are a powerful example of how to co-opt the intrinsically commercial language of billboards to subvert and resist neoliberal hegemony despite the failure to stop this regeneration. In the contemporary moment, when the combined effects of coronavirus, unforeseeable results of Brexit, governmental neglect and late Capitalism are increasing divisions between people, their commitment to interdisciplinary methods and collaborative, community-informed practice is more relevant now than ever.

© Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, all rights reserved, DACS 2020

Learn more about the artists here –

Loraine Leeson www.cspace.org.uk

Peter Dunn www.arte-ofchange.com

Bibliography:

Loraine Leeson & Peter Dunn. The Changing Picture, in: Photography/Politics: Two, eds. P. Holland, J. Spence & S, Watney, Comedia/Photography Workshop, London 1986, pp. 102-118.

Learn more about Peter Dunn Learn more about Loraine Leeson Read more Photography+ here