Lorna Robertson, part of Tate Britain’s curatorial team, examines the defining role Jo Spence had on British feminist photography.

If the lens of the camera is associated with the eye – and a woman places the camera to her eye – in doing so she is signifying her own active looking.

Jo Spence (1934-1992) was a British photographer whose life, career and work provide an insight into the shifting status of women artists during 1970s and 1980s in Britain. From a working class background and based in London for most of her life, Spence’s career spanned four decades from the early 1950s to her untimely death in 1992. Beginning in the commercial photography sector, Spence worked her way up to become an independent photographer. Spence is notable for making work on her own terms and is a key figure in the history of feminist photography.

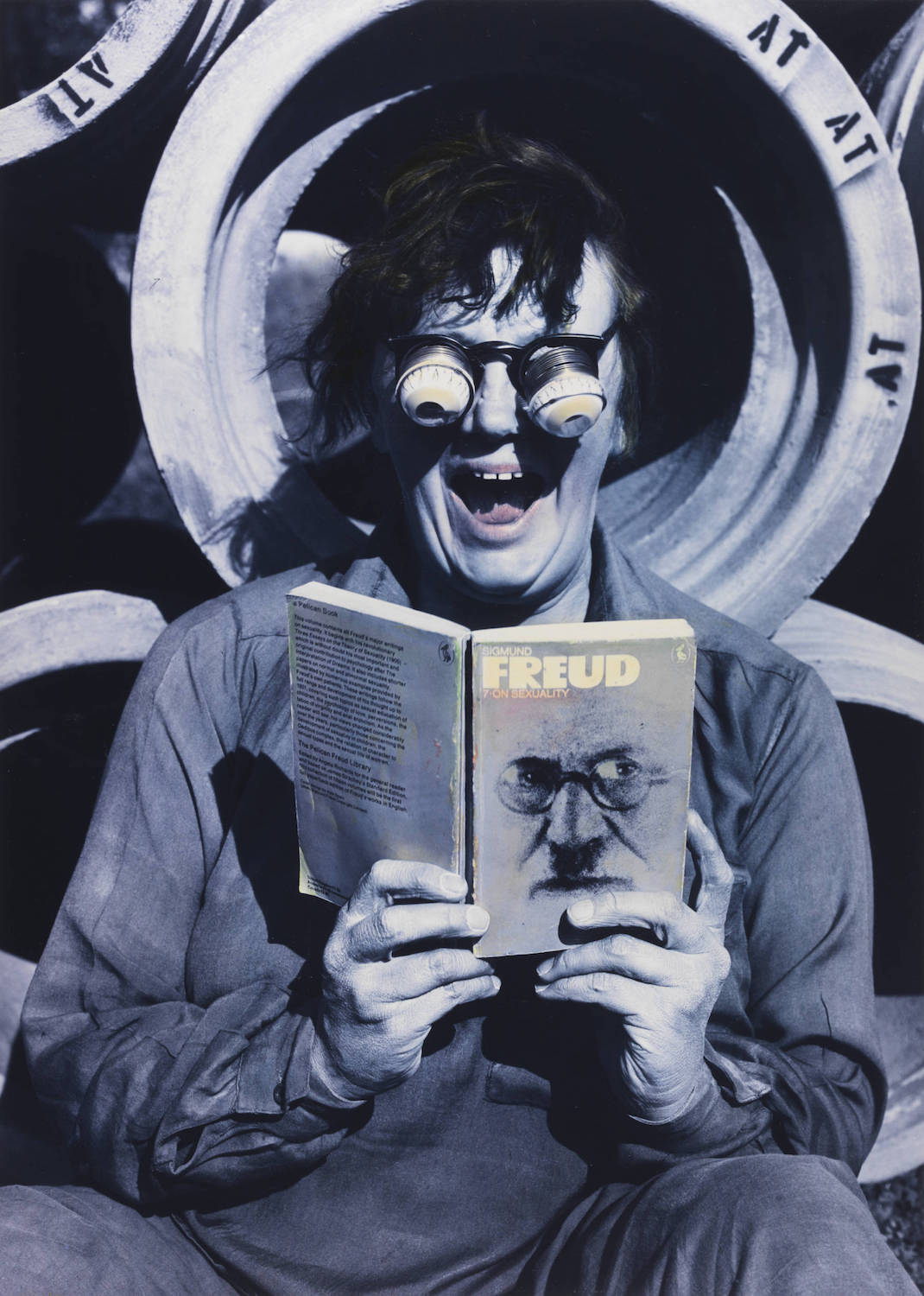

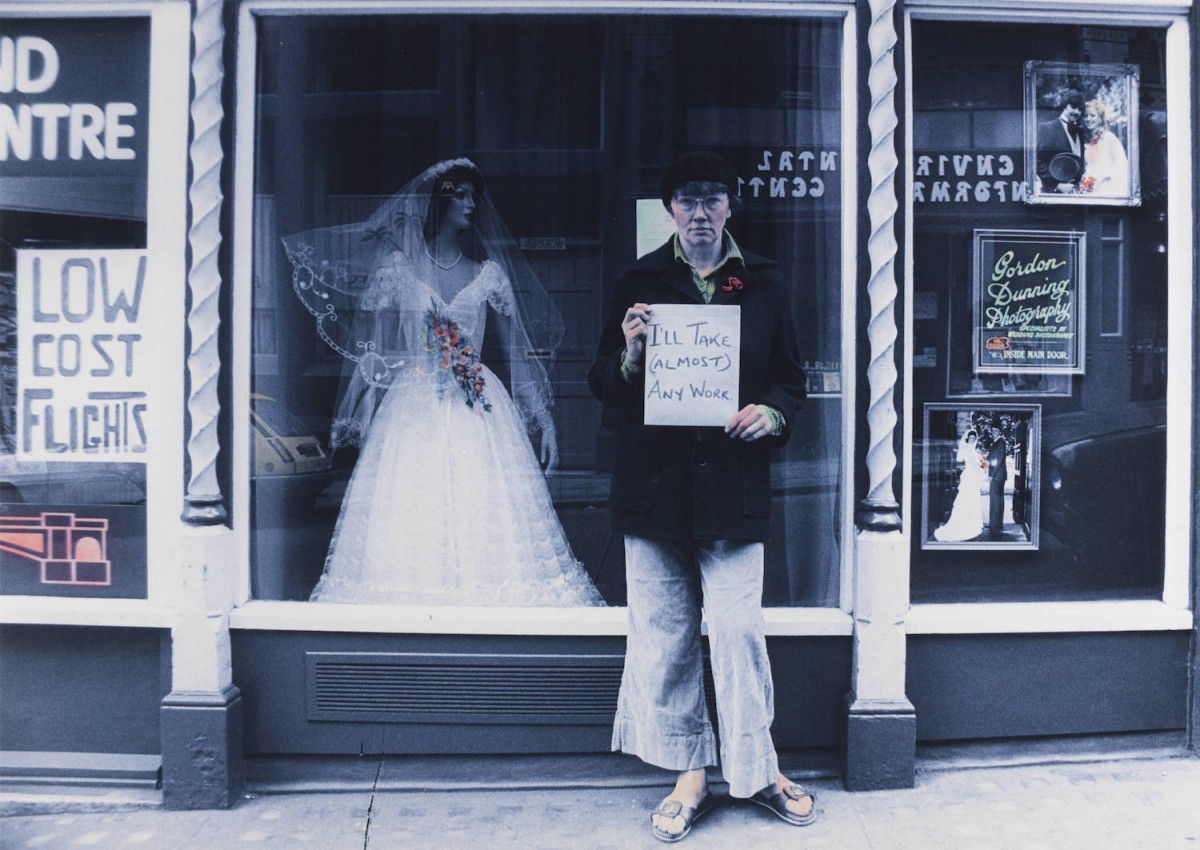

‘The Highest Product of Capitalism (after John Heartfield)’ 1979

Photograph, tinted gelatin silver print on paper; collaboration with Terry Dennett.

Presented by Tate Patrons 2014

© The Jo Spence Memorial Archive

Spence’s photography career began in the 1950s. She worked as a secretary for a commercial photography studio in north London and learnt photography on the job. Following this, she set up her own studio in Hampstead in 1967. As the 1970s unfolded, Spence became involved with left-wing politics. She started to move away from commercial photography and focus on her own socially conscious documentary projects. During this time, Spence met fellow photographer Terry Dennett who became a key collaborator in her career. Spence’s decision to break with commercial photography is explored in the 1979 work The Highest Product of Capitalism (after John Heartfield) by Dennett and Spence. The photograph shows Spence standing in front of a wedding photography shop. Spence looks sullenly into the camera and holds a sign that reads ‘I’ll Take (Almost) Any Work’. The scene suggests that by 1979, whilst Spence had successfully moved from the role of assistant into the role of photographer, she was no longer willing to work within a commercial photography environment that repressed women – both in terms of the images it produced and the professional roles it offered to them.

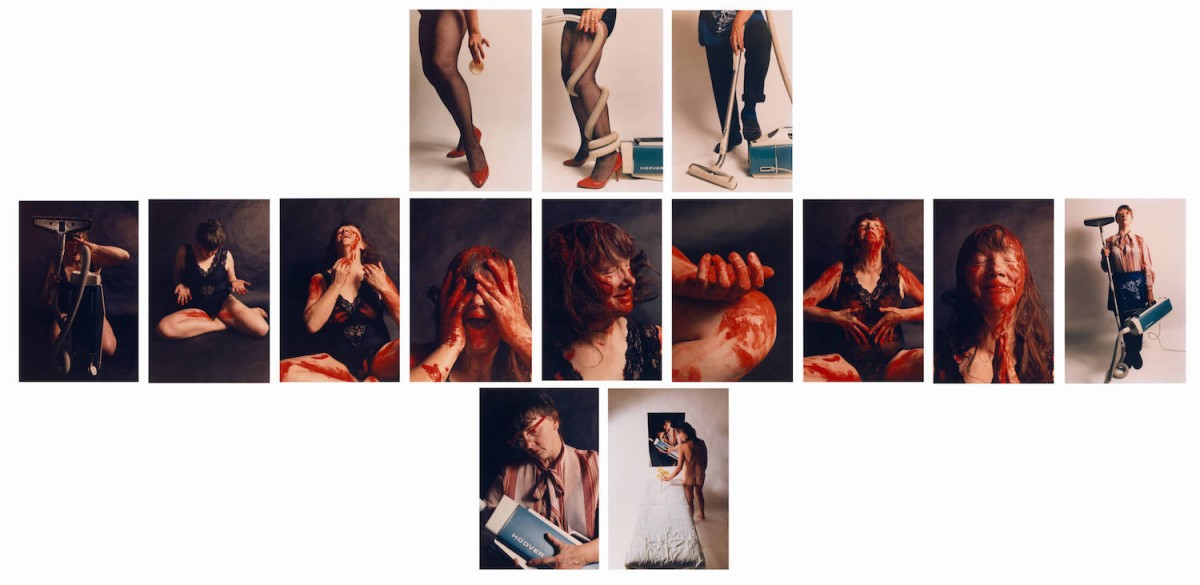

‘Remodelling Photo History: Realization 1981-2’

Photograph, tinted gelatin silver print on paper; collaboration with Terry Dennett.

Presented by Tate Patrons 2014

© The Jo Spence Memorial Archive

Into the early 1980’s Dennett and Spence continued to explore the ways that gender is constructed in photographic genres. The series Remodelling Photo History, 1981-2, points to the artifice behind photographs of women in advertising, journalism and documentary. Dennett and Spence used a non-naturalistic method that they termed ‘photo-theatre’. In the photographs, Spence poses with costumes and props that allow the viewer to see the artifice of these female personas – a glamorous mask is an exaggerated caricature and Spence’s brunette hair pokes out from underneath a blonde wig. The images are further denaturalised by the colours of the prints. The combination of silvery tone with translucent pink and green tints produces a synthetic petroleum-like quality. These visual markers work together to demonstrate that the various technical adjustments that may lie behind a photographic image and question the notion that a photograph is a truthful representation of a person or scene. In Remodelling Photo History, the humorous nature of Spence’s performance – conflating the roles of housewife and sexual object, conventionally kept separate in advertisements – is echoed by the playful reference to the kitsch quality of much hand-tinted photography.

In addition to her collaboration with Dennett, Spence was also involved with the 1970s women’s movement. From 1974-1980 Spence was a member of the photography collective The Hackney Flashers. The group came together to make work for the Hackney Trade Council’s 75th-anniversary celebrations, an opportunity that arose out of the Trade Council Women’s sub-committee who were looking for photographs of women and not just men. Working with documentary and agitprop photomontage, the group produced two touring exhibitions which aimed to make visible the invisible aspects of working class women’s lives in the Hackney area.

‘Libido Uprising Part I and Part II 1989’

Photographs, c-prints; Part I made up of 13 prints, collaboration with Rosy Martin, Part II made up of 1 print, collaboration with David Roberts.

Presented by Tate Patrons 2014

© The Jo Spence Memorial Archive

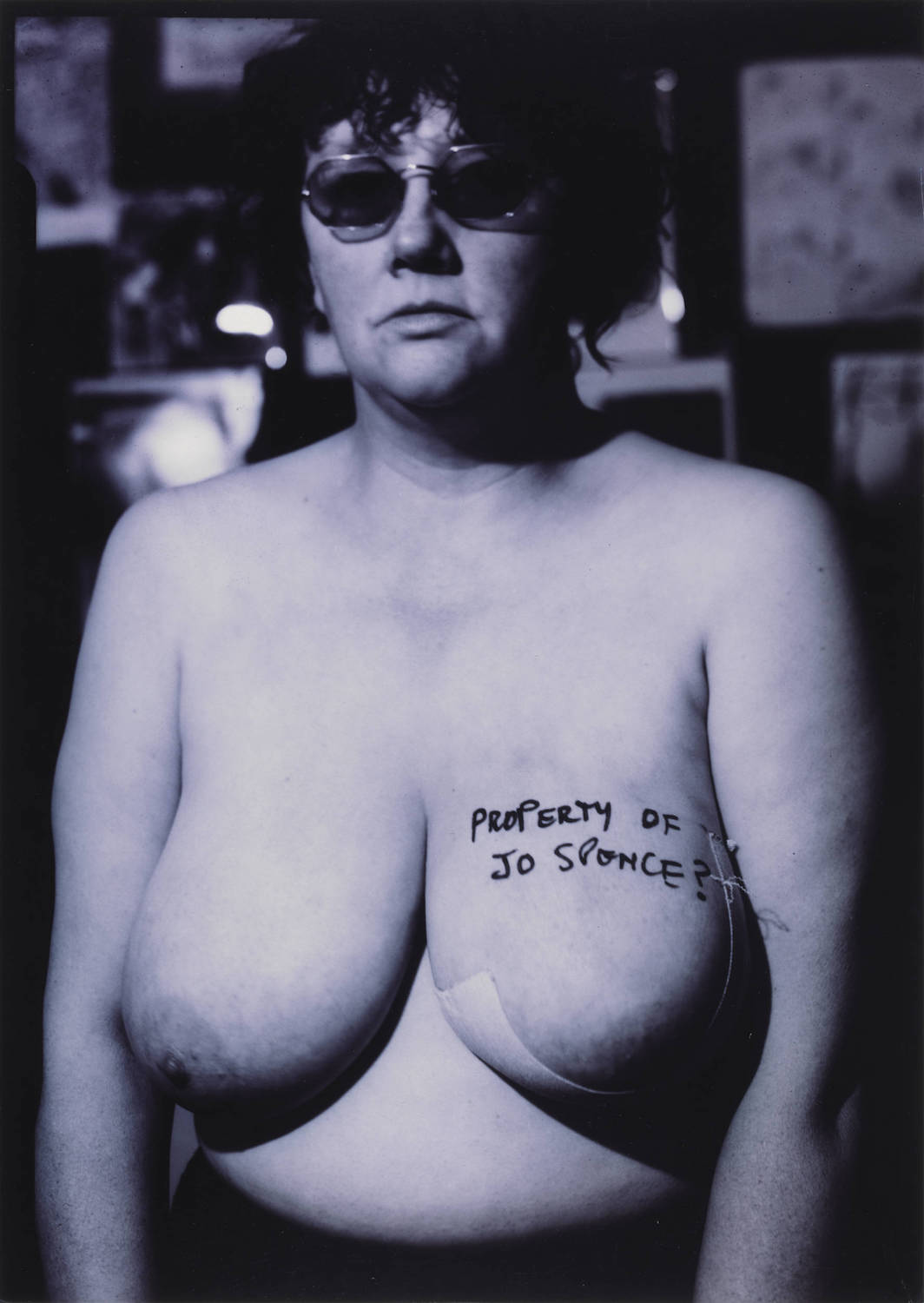

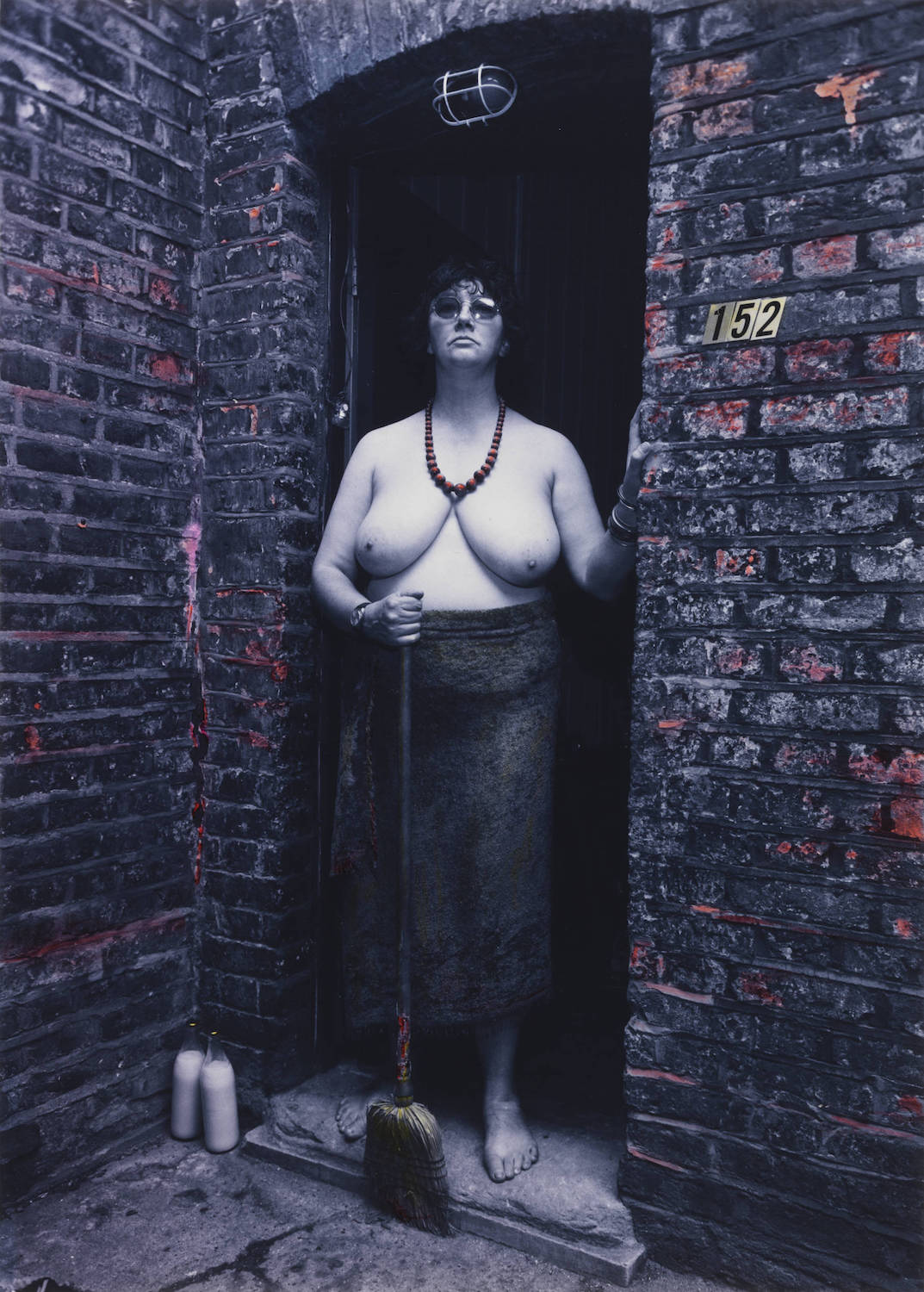

During the 1980’s, Spence’s practice took a new direction when in 1982 she was tragically diagnosed with breast cancer. Whilst in recovery she began to use photography as a method of self-counseling. From this, Spence later developed a method of working called phototherapy, which she devised in collaboration with the photographer Rosy Martin. One of the iconic works they collaborated on is Libido Uprising Part I and Part II. This large scale installation of 14 photographs show Spence acting our various roles as herself and her mother. The contrast between Spence’s sexual liberalism and her mother’s modesty explores a conflict between the domestic and the erotic in the family home, and reflects the shifting attitudes towards sexuality in post-war Britain.

In 1990, Spence was diagnosed with leukemia which took her life at the age of 58 in 1992. Her career reflects a shift in British visual culture during the 1970s and 1980s when women were increasingly using photography to explore the politics of representation. As Spence’s own career path demonstrates, women had to negotiate the existing frameworks of a cultural industry that would often position them as models and assistants rather than photographers. Yet when Spence did start to pick up the camera, she used photography to create her own visual language. She approached the question of representation in terms of class as well as gender, exploring invisible aspects of women’s lives such as work, motherhood, sexuality and health. The resulting images invite us to consider how photographs construct our perception of the world and the role we play within it.

The BP Spotlight: Jo Spence exhibition will be on display at Tate Britain until Autumn 2016.

For more on our Ideas Series, click here.