1st place Photoworks Graduate Award winner, Matthew Broadhead explores chronology, boundaries and ideas of home in Heimr.

Heimr

In 1965 and 1967 NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey organised field trips to Iceland for American astronauts to learn geology in locations described as ‘terrestrial analogue sites’. Also called ‘space analogues’, they are places on Earth with assumed past or present geological, environmental or biological conditions of a celestial body such as the Moon or Mars.

Described as “Probably the most moon-like of the field areas”, in a NASA document that acts as a ‘field training schedule’, the environments found in Iceland would have provided astronauts with the means to apply their practical knowledge of geology to validate their findings on the moon.

My field trip to Iceland was in response to the astronauts’ exploration of Earth before they went to the Moon, at the point when the geography of the landscape was largely imaginary. In the same way, I travelled beyond the frontier and into the lonely wilderness. Aspects of mythology, science, history and geography exist throughout the body of work in equal measure to present my findings. The title of the body of work, Heimr, refers to the use of the word in Eddic myth comprising of the Elder and Younger Edda that translates into ‘world’ but also ‘dwelling place’. I was compelled to make this reference as sending a man to the moon had complex implications for our species that had previously only called Earth ‘our world’ and ‘our home’. Within this, questions that ruminated in my mind about existential migration contributed to my personal experience of leaving ‘my world’ and becoming an ‘outlander’ to understand more fully what it means to belong and how that can be wrought with uncertainty.

Space is depicted in Eddic myth only as far as portions of it are the location of some action or person, and every trace I documented during my visit is intrinsically the same. The issue of anachronism in the sequencing of material reflects the nature of the evidence I found that left large gaps between each event holding only a vague sense of chronology. This creates tension between what the individual can learn through sensory experience, leaving the viewer with the understanding that there are more answers waiting to be uncovered or never found at all.

The themes of home, belonging and relating to your surroundings are very current but the documents you reference are historical. What is your impression of how these ideas have changed over the last few decades?

As I was working on Heimr I came to understand that ideologies behind home, belonging and how we negotiate our surroundings are crucial components of humanity and are the concern of individuals around the world, in the broadest sense. In the first instance, I found it enlightening to see how different the past was to the present but, ultimately, I found that this was superficial. What could be classed as fundamental does not change so easily over time. I admit that I do have a penchant for the eternal; what could be regarded as a romantic view on reality. The themes themselves have not changed, as I see it, but over the decades I see now how each generation forms new ideas about what it means to be part of a community and the difference between those with a manifest destiny who live their whole lives in one community at odds with individuals who migrate, making decisions about their fate based on more complex issues beyond their control.

Heimr marked the period of time I became aware of my displacement in the community I grew up in while becoming open minded about where I could settle in the future in a world moving in flux with the fast rate of globalization. A theoretical similarity between the historical documents and my photographs in this work is how we look at these things in the present and their existence as a petrification of the past.

I am critical of recording and the limitations that come with it but I believe I reverse this by using it as a device. It serves myself and my audience better if I don’t try to prove something universal but offer my exploration of this topic rendered in an idiosyncratic fashion.

How well do you think that photography documents and shapes our thoughts on migration, exploration and our compulsion to define or understand our ‘dwelling place’?

The 19th century was an age when many British travelled and brought back early photographs from places only the very privileged got to see and it has the same function now, where one can share their experiences and their travels with anybody. As we document the exotic in our midst, we continue to reinforce the notion of home in our ‘dwelling place’, the location we always return to when we leave.

Photographs give substance to reality, creating a fragment from the world. It makes experiences manageable and malleable, allowing the addition, removal and sequencing at will to maintain a complete essence of current perceptions of these events. In Heimr I speculated on the history of the visits by American astronauts in 1965 and 1967 in Iceland. I travelled there in person with my equipment to create material once I had a foundational context that shaped the itinerary for my investigations.

I am interested in the free movement of people and believe that photography is a tool that depends on the ability of the handler to render their experiences effectively. In those terms, as long as treaties such as the Schengen Agreement remain intact and continue to allow the populations of member states such as Iceland to roam across the continent without restriction, then the medium will continue to function as a useful learning device to experience these things for us to a certain point.

The nationalist developments in the United Kingdom in its impending divorce from the EU recently brought my attention to the struggle of co-existence when integrating into a community and the possibility of rejection based on prevailing political stances in contemporary society. In addition to this as well came the possibility of a breakup of the United Kingdom itself in light of a second referendum for Scotland proposed by SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon.

I believe that the onlooker should adopt a neutral stance when dealing with visual material of a political nature, as it is often used to put forward an agenda and support the argument of one side. With that, I believe that the limitation doesn’t lie with photography, but with us.

What lessons do you think can be learned about home by exploring unknown and new lands?

A primary finding in my research that elaborated on my rationale for creating an international body of work in Iceland is the term ‘existential migration’ coined by Dr. Greg Madison. In the article Existential Migration, based on his PhD research, he elaborates on this term in the abstract:

Phenomenological interviews with voluntary migrants, individuals who choose to leave their homeland to become foreigners in a new culture, reveal consistently deep themes and motivations, which could convincingly be labelled ‘existential’. Rather than migrating in search of employment, career advancement, or overall improved economic conditions, these voluntary migrants are seeking greater possibilities for self-actualising, exploring foreign cultures in order to assess their own identity, and ultimately grappling with issues of home and belonging in the world generally.

This is one aspect of why some people will live in other countries and continue to experience a longing to integrate for deeply profound reasons that are challenging to explain in simple terms.

Can you talk about the physical presentation of your work and the importance of referencing the chronological gaps?

The physical installation of Heimr in my graduate show at Brighton University included five framed C-type prints in a scattered formation in addition to a larger C-type print that was neither framed nor mounted and floated away from the wall using magnets. The simplicity of the presentation was intended to continue the reductive style of the photographs themselves, where my subject matter was recorded in the way documents in many scientific contexts are formed for their intrinsic value as data.

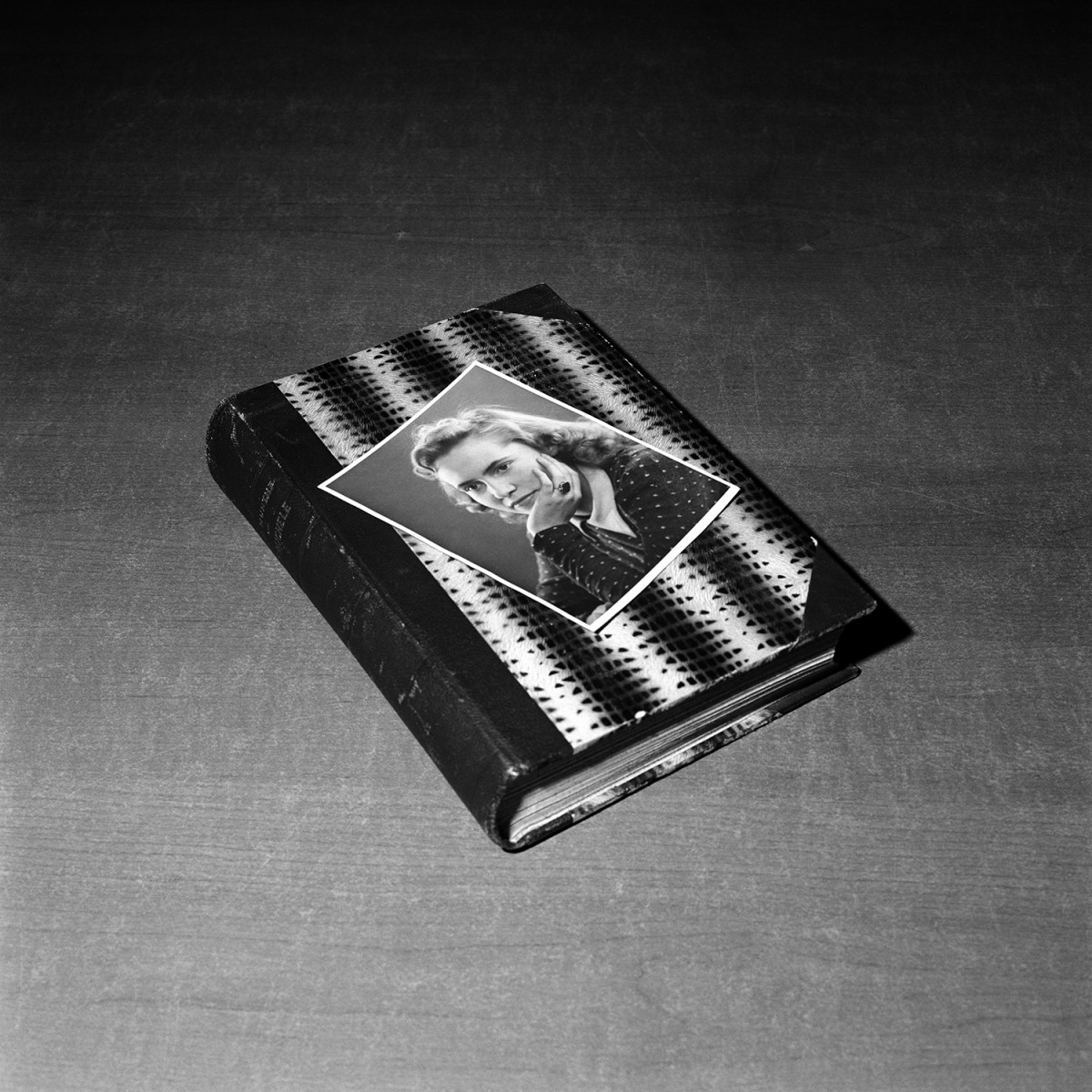

The concrete, historical events regarding the geological fieldtrips organized by NASA and the US Geological Survey function as the backbone of the project and run parallel with my musings on Nordic mythology; specifically what was recorded from oral accounts in Elder Edda and Prose Edda local to Iceland. With this, a relationship was formed between the structure of myth and featured material, considered as historical, that I wanted to tease out as a result of the intermingling present throughout the unabridged body of work. The inclusion of appropriated material produced by NASA and other contemporary sources was cross-referenced and verified for my own satisfaction that there is a degree of factuality to the evidence I was collating. My research formed the architecture of the itinerary inclusive of my geological field trips and visits to archives that I created the anachronistic material for Heimr in response to. If I was doing the project for an institution I would have been more rigid and objective in my resolve, but with the presence of a personal vein in the process I have an allowance for it to become more faulty with the warmth of a very human methodology. Being candid, sharing all the facets of work without upholding an illusion of it being a complete entity reveals this as an ongoing enquiry that will never reach its zenith. Each story in myth is an island in a sea of memory and history is the same.

See here for more of Matthew’s work.

For more showcases please click here.